How Perception Management Has Wrecked Reality

In The Secret Man, Bob Woodward’s book about his Watergate source Deep Throat, he notes, “Washington politics and secrets are an entire world of doubt.” And that was before Trump and cyberwar.

Even though Woodward knew the identity of his source — W. Mark Felt, then associate director of the FBI — what he could not be sure about was why Felt decided to gradually reveal the details of the Nixon administration’s illegal activities. Decades later, it is immeasurably more difficult to be sure about what motivates many sources of information, on and off the record, or to trust that what we hear and see via the media will turn out to be true.

In July 2005, Jeff Ruch, director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, issued a relevant but discouraging warning to the Subcommittee on Regulatory Affairs of the U.S. House Committee on Government Reform. “The federal government is suffering from a severe disinformation syndrome,” he said. It’s been mostly downhill from there, especially in the years since Donald Trump’s hostile takeover of the Republican Party turned national politics into surrealistic satire.

Weaponizing the term “fake news,” he and his accomplices have also effectively used it in a stream of misleading counter-attacks on critical press outlets. Hard as it is to believe, the targets have been mainly what used to be called mainstream media.

Fifteen years ago, Ruch’s reference to a “disinformation syndrome” referred specifically to surveys by his organization and the Union of Concerned Scientists revealing that federal scientists were routinely pressured to amend their findings. One in five scientists contacted said they were directed to inappropriately exclude or alter technical information, Ruch testified, and more than half reported cases where “commercial interests” forced the reversal or withdrawal of scientific conclusions.

But even then government agencies weren’t alone in confusing public understanding of crucial issues. Media outlets also contributed. One poignant example was Newsweek magazine’s Aug. 1, 2005 cover story on Supreme Court nominee John G. Roberts, which aggressively dismissed reports that Roberts was a conservative partisan. Two primary examples cited were the nominee’s role on Bush’s legal team in the court fight after the 2000 election, described by Newsweek as “minimal,” and his membership in the conservative Federalist Society, which was pronounced an irrelevant distortion.

The facts suggested a different appraisal, however. According to the Miami Herald, Roberts was a significant “legal consultant, lawsuit editor and prep coach” for Bush’s arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court in December 2000, and, as the Washington Post revealed, he was not just a Federalist Society member, but on the Washington chapter’s steering committee in the late 1990s.

More to the point, his roots in the conservative vanguard dated back to his days with the Reagan administration, when he provided legal justifications for recasting the way government and the courts approached civil rights, defended attempts to narrow the reach of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, challenged arguments in favor of busing and affirmative action, and even argued that Congress should strip the Supreme Court of its ability to hear broad classes of civil-rights cases. Nevertheless, most press reports on Roberts before his elevation — and since — echoed Newsweek’s excitement about his “intellectual rigor and honesty.”

Whether that early coverage qualifies as disinformation remains debatable. We may soon find out, as Roberts presides over the impeachment of a Republican president. However that turns out, his early press nevertheless serves as a relevant example of how journalists can assist political leaders, albeit unwittingly at times, in framing public awareness. As a practice, this is known in both government and public relations circles as “perception management.”

An evolving tactic

In 1987, the Department of Defense developed a propaganda and psychological warfare glossary that included an official definition of the term. Perception management incorporates tactics that either convey or deny information to influence “emotions, motives, and objective reasoning,” explained the DoD. For the military, the main targets are supposedly foreign audiences, and the goal is to promote “actions favorable to the originator’s objectives. In various ways, perception management combines truth projection, operations security, cover and deception, and psychological operations.”

The Reagan administration preferred a different term, “public diplomacy,” while the Bush administration called it “strategic influence,” but both referred to the same thing. In The Art of the Deal, Trump called it “truthful hyperbole,” a misleading euphemism for making things up.

Organized federal efforts to manipulate public perceptions date back at least to the 1950s, when people at more than 800 news and public information organizations carried out assignments for the CIA, according to The New York Times. By the mid-1980s, CIA Director Bill Casey had taken the practice to the next level: a systematic, covert “public diplomacy” apparatus designed to sell a “new product” — counter-insurgency in Central America — while reinforcing fear of communism, Nicaragua’s Sandinistas, Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi, and other designated enemies. Sometimes this involved “white propaganda,” stories and editorials secretly financed by the government, much like the videos and commentators later funded by the Bush administration. But other operations went “black;” that is, they pushed obviously false story lines.

One strategy was to insert psyops (psychological operations) specialists into newsrooms. In February 2000, a Dutch journalist revealed that CNN and the U.S. Army had agreed to do precisely that. The military was proud enough of this “expanded cooperation” with mainstream media to publicly acknowledge the effort.

As the Iraq War began, word leaked out that a new Pentagon Office of Strategic Influence was gearing up to sway leaders and public sentiment by disseminating sometimes-false stories. Facing censure, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld publicly denounced and supposedly disbanded it. But a few months later, he quietly funded a private consultant to develop another version. The apparent goal was to go beyond traditional information warfare with a new perception management campaign designed to “win the war of ideas.”

How does perception management work? One important tactic is to influence opinion by presenting theories as if they are facts. For example, “Bad as things are in Iraq,” began an Associated Press story in April 2004, “a quick U.S. departure would make them worse; encourage terrorists, set the stage for civil war, send oil prices spiraling, and ruin U.S. credibility throughout the Middle East.” Only two sources, both obscure Middle East scholars, were directly quoted in the story, plus unnamed “regional experts.”

Another approach is to “massage” the information, thus promoting the preferred spin. For example, stories that asserted the Iraq insurgency was losing momentum stressed the number of incidents during a specific period, but ignored data such as the number of wounded, civilian contractor deaths, and Iraqi military casualties.

Sometimes, though, the only approach that works is to fabricate the news.

Selling a war

The jailing of New York Times reporter Judith Miller for refusing to reveal how she learned the identity of CIA agent Valerie Plame, who was outed by columnist Robert Novak with White House assistance, sparked widespread condemnation from the press. Many journalists expressed deep concerns that their future ability to gain the trust of confidential sources would be undermined. Miller was, after all, a Pulitzer Prize-winner and the author of best-selling books; in short, an eminently reputable journalist who didn’t deserve punishment for protecting sources.

However, Miller’s real importance in the world of unnamed sources leads in a different direction. It illustrates how perception management techniques were applied during the Iraq War — something to keep in mind as Iran becomes a convenient election-year target. On April 21, 2003, the front page of the Times carried a story by Miller titled, “Aftereffects: Prohibited Weapons; Illicit Arms Kept Till Eve of War, An Iraqi Scientist Is Said to Assert.” In the lead paragraph, Miller claimed that she had discovered the proof of weapons of mass destruction, a central Bush Administration argument for the war.

The catch was that Miller’s story came entirely from secondary sources and had no independent confirmation. She never met the scientist and her copy was submitted to military officials before it was released. Yet, when Miller appeared on PBS’ NewsHour the same day, she said, “Well, I think they found something more than a smoking gun,” and turned her one unnamed scientist into several. Other news outlets quickly jumped on her article and statements to argue that the war was justified after all. By the next day, headlines across the country proclaimed “Illegal Material Spotted.”

As it turned out, the evidence wasn’t there, and a day later Miller was reporting that there had been a “paradigm shift.” Now she said MET Alpha was looking for “building blocks” and “precursors” to those weapons, another effort that ultimately proved fruitless. Next, her unnamed source informed her that the focus had changed to a search for scientists who could prove there had once been a WMD program.

This was only one of many stories produced by Miller that backed up administration arguments, only to be proven wrong or obsolete later. In many cases, she subsequently “clarified” or backed away from an initial characterization. But just as important as the content, disseminated widely through her appearances on programs like Oprah and Larry King Live, were her associations and actual sources of information.

By her own admission, the majority of stories she wrote about weapons of mass destruction came from Ahmad Chalabi, the exiled leader of the U.S.-backed Iraqi National Congress who hoped to replace Saddam Hussein. “I’ve been covering Chalabi for about 10 years,” Miller told Baghdad Bureau Chief John Burns, another New York Times Pulitzer Prize winner who became angry with her over an article on Chalabi. “He has provided most of the front page exclusives on WMD to our paper.” Furthermore, MET Alpha used “Chalabi’s intel and document network for its own WMD work,” she admitted.

Equally relevant was Miller’s association with the Middle East Forum, which promoted her as a speaker on “militant Islam” and “biological warfare.” Founded by Daniel Pipes, the forum was in the forefront of the push for an invasion of Iraq before the war. Pipes in turn maintained close relationships with Douglas Feith, an undersecretary at the Department of Defense, and leading neoconservative Richard Perle.

In Bob Woodward’s book on the Iraq War, Plan of Attack, Secretary of State Colin Powell described Feith as running a “Gestapo office” determined to find a connection between Saddam Hussein and 9/11. In A Pretext for War, a book on the abuse of U.S. intelligence agencies before and after 9/11, James Bamford described how Feith and Perle developed a blueprint for the Iraq operation while working for pro-Israeli think tanks. Their plan, called “A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm,” centered on taking out Saddam and replacing him with a friendly leader. “Whoever inherits Iraq,” they wrote, “dominates the entire Levant strategically.” The subsequent steps they recommended included invading Syria and Lebanon.

After joining the Bush administration, Feith created the Office of Strategic Influence. Senior officials have called it a disinformation factory. He later launched the Office of Special Plans (OSP). Officially, its job was to conduct pre-war planning. But its actual target was the media, policymakers, and public opinion. According to London’s Guardian newspaper, the OSP provided key people in the administration with “alarmist reports on Saddam’s Iraq.” To do that, it circulated cooked intelligence from its own unit and a similar Israeli group. There was also a close relationship with Vice President Cheney’s office.

According to Bamford, OSP’s intelligence unit cherry-picked the most damning items from the streams of U.S. and Israeli reports and briefed senior administration officials. “These officials would then use the OSP’s false and exaggerated intelligence as ammunition when attempting to hard-sell the need for war to their reluctant colleagues, such as Colin Powell, and even to allies like British Prime Minister Tony Blair,” he reports. Senior White House officials received the same briefings.

The final step was to get Powell to make the case to the UN. This was handled by the White House Iraq Group (WHIG), a secret office established to sell the war. WHIG provided Powell with a “script” for his speech, using information developed by Feith’s group. Much of it was unsourced material fed to reporters like Miller by the OSP. Such techniques continued to prove useful after the invasion.

Shaping the environment

Like other forms of perception management, the manipulation and misuse of reporters isn’t new. In the 1960s, the FBI used large dailies like the San Francisco Chronicle to place unfavorable stories and leak false information. In Chicago, such “friendly media” assisted with smears of black nationalist groups on the radio and in print. Sometimes reporters were unwittingly exploited, but often they knew what they were doing: writing dubious stories that made FBI speculation and falsehoods sound true. When challenged, they too vigorously protected their sources.

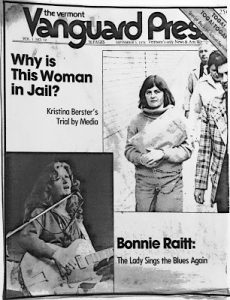

Vermont’s media saw perception management at work in 1978, when a young woman named Kristina Berster was caught crossing the border illegally from Canada into Vermont. The FBI knew only that she was a West German citizen and was wanted for something called “criminal association,” a crime that didn’t exist in the United States. But FBI Director William Webster realized that her arrest could help buttress his claims that urban terrorism was increasing. He was in the process of lobbying for more agents and expanded authority to investigate those who were “reasonably believed” to be involved in “potential” terrorist activities.

Initially, journalists presented the government’s version without asking many questions. After all, why else the high bail, 24-hour guard for the judge, metal detectors, and armed officers on the courthouse roof? As the trial proceeded in U.S. District Court in Burlington, new information about potential “threats” was distributed to the press, reinforcing the idea that foreign terrorism loomed over the Green Mountains.

However, once local reporters had time to observe the defendant, a small, fair-haired woman with a mild demeanor and open smile, the huge security team began to look like overkill. And as the media coverage shifted, the general public also gave the case a second look and the story gradually unraveled.

The verdict, delivered on Oct. 27, 1978 after more than five days of deliberations, was a felony and misdemeanor conviction for lying to a customs official, but acquittal on the crucial conspiracy charge. The government had lost its main case. Afterward, several jurors said that they found Berster’s situation compelling and expressed hope that the guilty verdict on minor charges wouldn’t prevent her from winning asylum.

But beyond this small New England state, the smear campaign rolled on. In New York City, a banner headline in the New York Post the day after Berster’s conviction trumpeted, “No Asylum for Terrorist.”

This story has a happy ending at least: When Berster returned home to Germany, the old charges against her were dropped. Still, it demonstrates how perception management works. Manipulating the press and exploiting fear are powerful tools, too often used to justify bigger budgets or intrusive security measures.

Today, controlling public opinion involves more than what was once simply labeled propaganda. Over the years, both business interests and governments have developed a creative toolbox of tactics to promote the stories they want to see and prevent others from being aired or published. In some cases, this involves what has become known as spin, or “white propaganda,” arguments that tend to move opinion in a specific direction.

For journalists, the pitfalls include institutional constraints, commercial imperatives, relationships with sources that have hidden agendas, the temptation to focus on easy targets, and a tendency toward self-censorship. There is also an increasing likelihood, exacerbated by the Internet and social media, that rumors or speculation will be confused with reality.

In other words, perception management is about more than censoring or pushing an individual story. Rather, it involves the creation of an environment that promotes false narratives, the uncritical acceptance of questionable assumptions, and media willing to exploit them.

As Noam Chomsky put it, “The point is not that the journalists or commentators are dishonest; rather, unless they happen to conform to the institutional requirements, they will find no place in the corporate media.” The fact that the interests of owners shape what is defined as news is one of the main structural “filters” underlying newsgathering, he notes.

When confronted with such a critique, many journalists reject it as “conspiracy” thinking. Translation: it’s paranoid, extreme, and therefore irrelevant. Especially now, when most reporters and unnamed sources are assumed to be part of the Trump “resistance.” Unlike any other employees, most journalists insist that they are free of direct supervisory control, outside influences, or serious bias, and thus free to pursue any story, wherever it leads.

But as anyone who has worked in a real news organization knows, every story involves a series of decisions and judgments about what is important, relevant, permissible and appropriate. And almost every source, from a disgruntled bureaucrat to Deep Throat, brings an agenda of his or her own. It may all add up to news, but that doesn’t make it true.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Greg Guma writes on his blog, For Preservation & Change, where this article was originally published.

All images in this article are from the author