New Hi-Tech Police Surveillance: The “StingRay” Cell Phone Spying Device

Blocked by a Supreme Court decision from using GPS tracking devices without a warrant, federal investigators and other law enforcement agencies are turning to a new, more powerful and more threatening technology in their bid to spy more freely on those they suspect of drug crimes. That’s leading civil libertarians, electronic privacy advocates, and even some federal judges to raise the alarm about a new surveillance technology whose use has yet to be taken up definitively by the federal courts.

StingRay cell phone spying device (US Patent photo)

The new surveillance technology is the StingRay (also marketed as Triggerfish, IMSI Catcher, Cell-site Simulator or Digital Analyzer), a sophisticated, portable spy device able to track cell phone signals inside vehicles, homes and insulated buildings. StingRay trackers act as fake cell towers, allowing police investigators to pinpoint location of a targeted wireless mobile by sucking up phone data such as text messages, emails and cell-site information.

When a suspect makes a phone call, the StingRay tricks the cell into sending its signal back to the police, thus preventing the signal from traveling back to the suspect’s wireless carrier. But not only does StingRay track the targeted cell phone, it also extracts data off potentially thousands of other cell phone users in the area.

Although manufactured by a Germany and Britain-based firm, the StingRay devices are sold in the US by the Harris Corporation, an international telecommunications equipment company. It gets between $60,000 and $175,000 for each Stingray it sells to US law enforcement agencies.

[While the US courts are only beginning to grapple with StingRay, the high tech cat-and-mouse game between cops and criminals continues afoot. Foreign hackers reportedly sell an underground IMSI tracker to counter the Stingray to anyone who asks for $1000. And in December 2011, noted German security expert Karsten Nohl released “Catcher Catcher,” powerful software that monitors a network’s traffic to seek out the StingRay in use.]

Originally intended for terrorism investigations, the feds and local law enforcement agencies are now using the James Bond-type surveillance to track cell phones in drug war cases across the nation without a warrant. Federal officials say that is fine — responding to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request filed by the Electronic Freedom Foundation (EFF) and the First Amendment Coalition, the Justice Department argued that no warrant was needed to use StingRay technology.

“If a device is not capturing the contents of a particular dialogue call, the device does not require a warrant, but only a court order under the Pen Register Statute showing the material obtained is relevant to an ongoing investigation,” the department wrote.

The FBI claims that it is adhering to lawful standards in using StingRay. “The bureau advises field officers to work closely with the US Attorney’s Office in their districts to comply with legal requirements,” FBI spokesman Chris Allen told the Washington Post last week, but the agency has refused to fully disclose whether or not its agents obtain probable cause warrants to track phones using the controversial device.

And the federal government’s response to the EFF’s FOIA about Stingray wasn’t exactly responsive. While the FOIA request generated over 20,000 records related to StingRay, the Justice Department released only a pair of court orders and a handful of heavily redacted documents that didn’t explain when and how the technology was used.

The LA Weekly reported in January that the StingRay “intended to fight terrorism was used in far more routine Los Angeles Police criminal investigations,” apparently without the courts’ knowledge that it probes the lives of non-suspects living in the same neighborhood with a suspect.

Critics say the technology wrongfully invades technology and that its uncontrolled use by law enforcement raised constitutional questions. “It is the biggest threat to cell phone privacy you don’t know about,” EFF said in a statement.

ACLU privacy researcher Christopher Soghoian told a Yale Law School Location Tracking and Biometrics Conference panel last month that “the government uses the device either when a target is routinely and quickly changing phones to thwart a wiretap or when police don’t have sufficient cause for a warrant.”

“The government is hiding information about new surveillance technology not only from the public, but even from the courts,” ACLU staff attorney Linda Lye wrote in a legal brief in the first pending federal StingRay case (see below). “By keeping courts in the dark about new technologies, the government is essentially seeking to write its own search warrants, and that’s not how the Constitution works.”

Lye further expressed concern over the StingRay’s ability to interfere with cell phone signals in violation of Federal Communication Act. “We haven’t seen documents suggesting the LAPD or any other agency have sought or obtained FCC authorization,” she wrote.

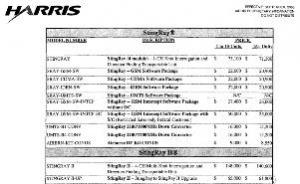

StingRay pricing chart (publicintelligence.net)

Advocates also raised alarms over another troubling issue: Using the StingRay allows investigators to bypass the routine process of obtaining fee-based location data from cell service providers like Sprint, AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile and Comcast. Unlike buying location data fro service providers, using StingRay leaves no paper trail for defense attorneys.

Crack defense attorney Stephen Leckar who scored a victory in a landmark Supreme Court decision over the feds’ warrantless use of a GPS tracker in US v. Jones, a cocaine trafficking case where the government tracked Jones’ vehicle for weeks without a warrant, also has concerns.

“Anytime the government refuses to disclose the ambit of its investigatory device, one has to wonder, what’s really happening,” he told the Chronicle. “If without a warrant the feds use this sophisticated device for entry into people’s homes, accessing private information, they may run afoul of a concurring opinion by Justice Alito, who ruled in US v Jones whether people would view unwarranted monitoring of their home or property as Constitutionally repugnant.”

Leckar cited Supreme Court precedent in Katz v. US (privacy) and US v. Kyllo (thermal imaging), where the Supreme Court prohibited searches conducted by police from outside the home to obtain information behind closed doors. Similar legal thinking marked February’s Supreme Court decision in a case where it prohibited the warrantless use of drug dogs to sniff a residence, Florida v. Jardines.

The EFF FOIA lawsuit shed light on how the US government sold StingRay devices to state and local law enforcement agencies for use specifically in drug cases. The Los Angeles and Fort Worth police departments have publicly acknowledged buying the devices, and records show that they are using them for drug investigations.

“Out of 155 cell phone investigations conducted by LAPD between June and September 2012, none of these cases involved terrorism, but primarily involved drugs and other felonies,” said Peter Scheer, director of the First Amendment Center.

The StingRay technology is so new and so powerful that it not only raises Fourth Amendment concerns, it also raises questions about whether police and federal agents are withholding information about it from judges to win approval to monitor suspects without meeting the probable cause standard required by the Fourth. At least one federal judge thinks they are. Magistrate Judge Brian Owsley of the Southern District of Texas in Corpus Christi told the Yale conference federal prosecutors are using clever techniques to fool judges into allowing use of StingRay. They will draft surveillance requests to appear as Pen Register applications, which don’t need to meet the probable cause standards.

“After receiving a second StingRay request,” Owsley told the panel, “I emailed every magistrate judge in the country telling them about the device. And hardly anyone understood them.”

In a earlier decision related to a Cell-site Simulator, Judge Owsley denied a DEA request to obtain data information to identify where the cell phone belonging to a drug trafficker was located. DEA wanted to use the suspect’s E911 emergency tracking system that is operated by the wireless carrier. E911 trackers reads signals sent to satellites from a cell phone’s GPS chip or by triangulation of radio transmitted signal. Owsley told the panel that federal agents and US attorneys often apply for a court order to show that any information obtained with a StingRay falls under the Stored Communication Act and the Pen Register statute.

DEA later petitioned Judge Owsley to issue an order allowing the agent to track a known drug dealer with the StingRay. DEA emphasized to Owsley how urgently they needed approval because the dealer had repeatedly changed cell phones while they spied on him. Owsley flatly denied the request, indicating the StingRay was not covered under federal statute and that DEA and prosecutors had failed to disclose what they expected to obtain through the use of the stored data inside the drug dealer’s phone, protected by the Fourth Amendment.

“There was no affidavit attached to demonstrate probable cause as required by law under rule 41 of federal criminal procedures,” Owsley pointed out. The swiping of data off wireless phones is “cell tower dumps on steroids,” Owsley concluded.

But judges in other districts have ruled favorably for the government. A federal magistrate judge in Houston approved DEA request for cell tower data without probable cause. More recently, New York Southern District Federal Magistrate Judge Gabriel Gorenstein approved warrantless cell-site data.

“The government did not install the tracking device — and the cell user chose to carry the phone that permitted transmission of its information to a carrier,” Gorenstein held in that opinion. “Therefore no warrant is needed.”

In a related case, US District Court Judge Liam O’Grady of the Northern District of Virginia ruled that the government could obtain data from Twitter accounts of three Wikileakers without a warrant. Because they had turned over their IP addresses when they opened their Twitter accounts, they had no expectation of privacy, he ruled.

“Petitioners knew or should have known that their IP information was subject to examination by Twitter, so they had a lessened expectation of privacy in that information, particularly in light of their apparent consent to the Twitter terms of service and privacy policy,” Judge O’Grady wrote.

A federal judge in Arizona is now set to render a decision in the nation’s first StingRay case. After a hearing last week, the court in US v. Rigmaiden is expected to issue a ruling that could set privacy limits on how law enforcement uses the new technology. Just as the issue of GPS tracking technology eventually ended up before the Supreme Court, this latest iteration of the ongoing balancing act between enabling law enforcement to do its job and protecting the privacy and Fourth Amendment rights of citizens could well be headed there, too.