Why US Governments Failed to Destroy the Cuban Revolution

Washington’s failure to overthrow communism in Cuba has been a source of extreme irritation for successive American leaders. The inability of the world’s strongest country to bend Cuba to its will has been nothing if not remarkable.

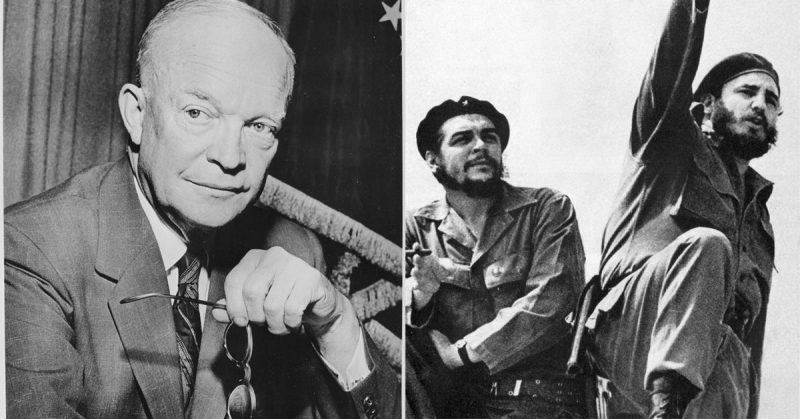

Even so, a closer examination of the United States-Cuba rivalry reveals some glaring reasons why the superpower was unable to destroy the revolution. One must return to the really critical period of the late 1950s and early 1960s. American imperial planners, and other supporters of the Monroe Doctrine of US domination over the Western hemisphere, may lay the blame squarely at the door of Dwight D. Eisenhower.

It was General Eisenhower who held the post of US president for eight years, until January 1961. During this time Fidel Castro‘s rebels successfully fought their guerrilla war against the dictator that Eisenhower was propping up, Fulgencio Batista. Castro came seamlessly to power on New Year’s Day 1959, and then managed to establish his government’s control in Cuba.

Eisenhower himself had recent history of intervening in Latin America. During the summer of 1954, he sanctioned the ousting of the democratically elected Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz. In doing so, Guatemala was sent careering into a state of misery which it has yet to emerge from. The previous year Eisenhower, with some British cajoling, had also toppled a nationalist government in oil rich Iran, with the autocratic Shah installed.

From the late 1950s the Eisenhower administration, now in its waning years, would fortunately be unable to repeat such a move in Cuba. Richard Gott, the English author and scholar of Cuban history, wrote that

“the Eisenhower government, as much from inertia as from conservatism or anti-communism, had contently gone on supporting Batista, although with a growing lack of conviction. While continuing to supply weapons, it never provided enough to allow Batista a military victory”. (1)

Castro’s influence in Cuba began to increase gradually from early 1957 as his men, from their Sierra Maestra base in south-eastern Cuba, staged skilful coordinated assaults against Batista’s forces. Eisenhower, meanwhile, paid little attention to what was occurring in Cuba at this point. Despite its close proximity on the map, Eisenhower had never visited the Caribbean island before.

Propaganda poster in Havana, 2012 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Cuba was taken for granted as a US possession, since the Americans replaced Spanish hegemony there in 1898. American landholders owned vast tracts of the country at the expense of landless Cuban peasants. By 1958, almost 75% of Cuba’s agricultural terrain was concentrated in the hands of a minority, with the best land belonging to US monopolies. (2)

On 14 March 1958, the Eisenhower administration suspended weapons sales to Batista, ostensibly because the latter had been killing his own people with US equipment. Just prior to the arms embargo, Batista’s units received a fresh supply of US weapons anyway (3). Yet Eisenhower was, in the short-term, seeking to replace the increasingly unpopular Batista with someone more amenable.

Source: War History Online

On 28 June 1958 Batista attacked Castro’s guerrilla stronghold, the Sierra Maestra mountains, with 12,000 soldiers, many of whom were carrying American-made arms. Batista’s forces for this fateful incursion, including 7,000 poorly trained conscripts, still outnumbered the rebels dozens of times over; but after a six week offensive in which the Batista regime also enjoyed complete air superiority, the attack failed to achieve its objectives. Castro was joyous. He told foreign journalists that his domain of operations was an impenetrable fortress, “Every entrance to the Sierra Maestra is like the pass at Thermopylae”.

In repelling this attack, the guerrillas demonstrated their prowess in warfare. The CIA’s “more progressive elements”, as Gott recounted, continued to look “favourably on Castro” well into 1958 (4). The New York Times had likewise been sympathetic to Castro’s cause, before changing its tune later.

By early autumn 1958, it was becoming obvious that the rebels were winning the war. An unknown quantity, patently nationalist in nature, was challenging American supremacy 90 miles from the US mainland. Were Batista ousted, and the guerrillas victorious, this would represent a clear defeat for American foreign policy. Had Batista been compelled by the US government to leave Cuba, and someone else put in his place, it might have taken some of the wind out of the rebels’ sails; whose focus was concentrated entirely on the despot and his underlings.

Towards the latter stages of 1958, a force of a few thousand US marines could have been dispatched to Cuba, with the aim of thwarting the guerrillas and “restoring order”. Hindsight makes everything easier but the marines’ presence would have boosted Batista’s flagging soldiers, while dealing a psychological blow to the rebels. Eisenhower was surely aware that such a move would provoke further negative responses in Latin America.

During May 1958 vice-president Richard Nixon, while touring the Western hemisphere, had received hostile reactions from protesters. This was mainly due to ongoing US support for brutal Latin American dictators, such as Alfredo Stroessner (Paraguay) and Rafael Trujillo (Dominican Republic). Nevertheless Cuba was a unique case with Washington. It had been a virtual US colony for six decades. There were four previous American military interventions in Cuba by the marines in the early 20th century, so as to reinforce weak US-friendly governments and protect elite concerns. The prevalence of American troops in Cuba would have had the usual demoralising effect on its people.

In late August 1958 the guerrillas were implementing their decisive moves, with not an American combatant in sight. By November 1958, the US State Department and the CIA were predicting Castro’s victory “unless a mediated solution could be found” (5). On 9 December 1958 a clandestine envoy dispatched by Eisenhower, William D. Pawley, went to see Batista. Pawley urged him to accept exile in Daytona Beach, Florida. The offer was refused.

On 23 December 1958, CIA director Allen Dulles informed Eisenhower that,

“Communists and other extreme radicals appear to have penetrated the Castro movement. If Castro takes over, they will probably participate in the government” (6).

Unsettled by this news, Eisenhower expressed regret having not been told earlier. At this late date, the “Great General” placed hopes on some “third force” emerging to somehow supersede Castro.

Instead, on 1 January 1959 the revolution swiftly came to power amid much fanfare. The next day, in Santiago de Cuba in the country’s south-east, Castro gave his first speech to the Cuban public and said,

“This time it will not be like 1898, when the North Americans came and made themselves masters of our country”. (7)

Statements likes this should have left Eisenhower and Nixon no doubt as to which path Cuba would now take. On 3 March 1959, Castro nationalised the Cuban Telephone Company owned by the US conglomerate, ITT (International Telephone & Telegraph); and he also lowered the rates to affordable standards, impacting on US profits. American corporations had dominated Cuba’s telephone and electric services. By 1956 American businesses controlled 90% of these industries in Cuba, as a US Department of Commerce report highlighted. (8)

On 7 March 1959 Castro asked that Washington hand over Guantanamo Bay, a request which was quickly rejected. In the early summer of 1959, the Cuban government began instituting a land reform act, prompting an official note of protest from the US capital. Gott noted how,

“The law struck at foreign landowners, of whom the majority were American” (9).

In June 1959 Eisenhower and the NSC, convening again, decided unequivocally that Castro would have to go.

As any government assumes control by way of revolution or coup d’etat, a crucially important Consolidation Phase ensues. Throughout 1959 Castro’s position was very vulnerable. He had still to establish his authority in Cuba, and there was no financial or military support yet forthcoming from the USSR. In their defence of Cuba in 1959, the revolutionary leaders could rely only on the guerrilla soldiers who secured them power. Batista’s remaining forces were either fleeing the island in disarray, or being tracked down by the victorious rebels.

The foundation of a Cuban army did not begin until mid-October 1959, to be commanded by Raul Castro, and called the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces. It would number 40,000 troops by early 1961. (10)

President Eisenhower, with CIA input, started planning an illegal invasion of Cuba more than a year after Castro had taken power, in the spring of 1960. By then the sands of time were already moving fast against the US government. After further delays it would be another year before the attack occurred, three months following Eisenhower’s departure from office.

In April 1961 it was too late for a US-run invasion of Cuba to succeed, certainly one involving Cuban exile soldiers. Even with strong American air cover, it would be difficult indeed for 1,500 exiles to defeat a Cuban army numbering at least 40,000 men – under the highly motivated leadership of the new defence minister, Raul Castro. Three days after the attack’s failure, Eisenhower ungraciously grilled the new president John F. Kennedy in a meeting at Camp David. Kennedy felt that his predecessor had handed him a “burning issue” that should have been resolved before 1961. (11)

In early August and late September 1961, the Soviet Union signed two arms assistance agreements with Cuba, as a military aid program was adopted between Moscow and Havana. Noam Chomsky, the American historian and analyst, outlined that in February 1962 the US Joint Chiefs of Staff approved a plan “to lure or provoke” Cuba’s government “into an overt hostile reaction against the United States”. The Joint Chiefs, with General Curtis LeMay and General Thomas Power straining at the leash, would then launch a frontal attack to “destroy Castro with speed, force and determination”. (12)

It can be acknowledged that Generals LeMay and Power, close colleagues for many years, were also particularly dangerous men. They were described by officers under them as “not stable” mentally which tells its own story (13). Both LeMay and Power pushed for an invasion of Cuba. More broadly in the Cold War they advocated massive nuclear strikes on the Soviet Union, breaching official protocol more than once to pursue their own hawkish strategies.

Evolving US plans to attack Cuba were becoming increasingly reckless. The Attorney General Robert Kennedy warned that a large-scale invasion of Cuba, in the early 1960s, would “kill an awful lot of people” but his main concern was “we’re going to take an awful lot of heat on it” (14). By 1962, US military planners were outlining a desire not to “directly involve the Soviet Union” (15). This was no longer possible, as the Cuban Missile Crisis later that year reveals.

At the revolution’s outset the Kremlin initially showed little interest in Cuba, and knew nothing of Castro’s political leanings. Alexander Alexeyev, the first Soviet diplomat to visit Cuba, arrived in October 1959. Soviet-Cuban economic ties did not gain a head of steam until mid-February 1960, when a commercial agreement was signed. Diplomatic relations were formally established between Cuba and the USSR on 8 May 1960, one year and four months into the revolution.

Lieutenant-Colonel Donald J. Goodspeed, an experienced Canadian military historian who analysed revolutions and coup d’etats, wrote that “what the rebels most need is time” after taking power when they are at their “period of greatest weakness”. (16)

Castro’s new government was granted ample time by Eisenhower. After Castro’s takeover of the Cuban Telephone Company at the expense of US-owned ITT, Eisenhower chaired a National Security Council (NSC) meeting on 26 March 1959, in part to discuss what was taking place in Cuba. Eisenhower asked openly whether the Organisation of American States (OAS) could act against Castro (17). The president was informed that scenario was impossible, as the OAS could not intervene militarily in other countries, and Cuba had at that point not been suspended from the organisation.

In late March 1959, Eisenhower decided upon neither a coup d’etat nor an invasion of Cuba. A coup would most likely have failed. Castro had the loyalty of his advisers and the guerrilla forces, not to mention the Cuban people. An invasion was, once more, the sole means of toppling the revolution.

Lieutenant-Colonel Goodspeed wrote that in order to oust a foreign administration, particularly a centralised one like Castro’s,

“the important members of the existing government must be neutralised so that their writ can no longer run throughout the nation… In even the oldest kingdom or the most legalistic republic the business of governing is actually done, not by tradition or precedent, but by individuals. When these men are disposed of, their control also vanishes”. (18)

From a US imperial standpoint, for Eisenhower to eliminate Castro’s control he would have to remove the Cuban leader; along with other key members of the revolution, like Raul Castro, Che Guevara and Manuel Pineiro. Goodspeed recognised that with an early intervention,

“the swifter the stroke the greater the surprise. Government forces have no time to rally, no time even to think of what would be the best line of resistance”. (19)

As the months slipped by in 1959, Castro’s government was sinking its first tentative roots into Cuba’s fertile soil. Foreign recognition was inevitably sought. In June 1959, Guevara was sent on distant ventures to garner support, visiting such countries as Pakistan, India, Yugoslavia and Egypt. When in Cairo, Guevara made contact with the Soviet embassy there.

In the spring of 1959, the American government agreed to acts of “sabotage” against Cuba, in reality terrorism. Beginning in May 1959, the CIA was also supplying anti-communist guerrillas inside Cuba with weaponry. The first attacks consisted of incendiary and bombing raids by Cuban exile pilots, departing from Miami in US airplanes. This terrorism was doomed to failure from the beginning. The real centres of power, Castro’s military and political apparatus, went untouched. This would be the case again and again. It is quite amazing that Eisenhower, a former World War II Supreme Commander, did not apparently discern this. The terrorist acts against Cuba increased in frequency under Kennedy from late 1961.

The bombing was directed at Cuban industrial and agricultural centres, along with targeting its urban areas. The attacks did not affect Castro’s popularity, as was erroneously expected. It led to a siege mentality and, if anything, strengthened the government’s position further. The arming of anti-communists in Cuba was bound not to prevail either. These subversive elements lacked the backing of Cuba’s people, and they did not have the numbers to defeat the growing military forces harnessed by the Castro brothers.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree. He is interested in writing primarily on foreign affairs, having been inspired by authors like Noam Chomsky. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Notes

1 Richard Gott, Cuba: A new history (Yale University Press, 20 Aug. 2004), p. 164

2 Cuba Platform, “Cuban Land Reform”, https://cubaplatform.org/land-reform

3 Rex A. Hudson, Cuba: A Country Study (Department of the Army; 4th ed edition, 1 January 2003), p. 288

4 Gott, Cuba: A new history, p. 164

5 Thomas M. Leonard, Fidel Castro: A biography (Greenwood, 30 Jun. 2004), p. 44

6 Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, Foreign Relations, 1958-1960, Volume VI, p. 302

7 Nigel D. White, The Cuban Embargo under International Law (Routledge; 1 edition, 3 Nov. 2014), p. 68

8 Timothy M. Gill, The Future of U.S. Empire in the Americas: The Trump Administration and Beyond (Routledge; 1 edition, 24 Mar. 2020)

9 Gott, Cuba: A new history, p. 171

10 Hudson, Cuba: A Country Study, p. 288

11 Nestor T. Carbonell, Why Cuba Matters: New Threats in America’s Backyard (Archway Publishing, 27 May 2020)

12 Noam Chomsky, Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance (Penguin, 1 January 2004), p. 83

13 Richard Rhodes, “The General and World War III”, The New Yorker, 12 June 1995

14 Noam Chomsky, Who Rules The World? (Metropolitan Books, Penguin Books Ltd, Hamish Hamilton, 5 May 2016), p. 105

15 Chomsky, Hegemony or Survival, p. 83

16 Donald J. Goodspeed, The Conspirators (Macmillan, 1 Jan. 1962), pp. 231-232

17 Office Of The Historian, Memorandum of Discussion at the 400th Meeting of the National Security Council, Washington, 26 March 1959

18 Goodspeed, The Conspirators, p. 225

19 Goodspeed, The Conspirators, p. 228

Featured image: Raúl Castro, left, with has his arm around second-in-command, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, in Cuba. In their Sierra de Cristal Mountain stronghold south of Havana, in 1958 during the Cuban Revolution. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)