Today’s Plutocrats Seek to Recreate 19th-century Dystopia, Child Labour Rampant in Asia, Serfdom on the Rise Here

“The disparity in income between the rich and the poor is merely the survival of the fittest. It is the working out of a law of nature and a law of God.” –John D. Rockefeller, 1894.

During the first 70 years that followed this pronouncement by one of the 19th-century’s leading “robber barons,” the worst excesses of unfettered free enterprise were curbed by government regulations, increases in the minimum wage, and the growth of the labour movement. Strong unions and progressive governments combined to have wealth distributed less inequitably. Social safety nets were provided to help those in need.

Corporate owners, executives, and major shareholders resisted all these moderate reforms. Their operations had to be forcibly humanized. They always resented having even a small fraction of their profits diverted into wages, taxes, and social benefits; but until the mid-1970s and early ‘80s they couldn’t prevent it. Now they can.

Empowered by international trade agreements and the global mobility of capital, they can overcome virtually all political and labour constraints. They are free once more, as they were in the 1800s, to maximize profits and exploit workers, to control or coerce national governments, to re-establish the survival of the fittest as the socioeconomic norm.

This resurgence of corporate power is eroding a century of social progress. We are in danger of reverting to the kind of mass poverty and deprivation that marked the Victorian era. Indeed, this kind of corporate-decreed barbarism and inequality is already rampant in many developing countries, and even in some developed one. Including Canada.

Millions of people in this country have been forced to live in poverty by the outsourcing of good-paying industrial jobs under “free trade” and the erosion of social benefits. For them, a reversion to the bleak era of the 19th-century robber barons is already well underway.

Middle-class Canadians, of course, still cling to good jobs and live in relative comfort, but many are not nearly as secure in their lifestyle as they seem to think. They don’t know how badly their forebears were mistreated in the workplaces of the 1800s, so the prospect of a reversion to Victorian times doesn’t worry them. It should.

A brief history lesson may therefore be in order.

Industrial serfdom

Working hours in the mines and factories were from sunrise to sunset, about 72 hours a week. Wages, in 1910 currency, averaged less than $3 a day. Workers had to live in shacks or overcrowded tenements. They couldn’t afford carpets on the floor or even dishes for their meals.

Most workplaces were dirty, dimly lit, poorly heated. In many factories there were no guards on saw-blades, pulleys, or other dangerous machinery, because owners were not held responsible for industrial accidents. Workers took jobs at their own risk. If they were killed or injured at work, as many thousands were, they were blamed for their own “carelessness.” Uncounted thousands also died of tuberculosis, pneumonia, and other diseases caused by inadequate heat or sanitation.

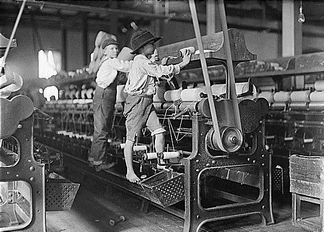

Conditions in the mines were especially bad, with most miners dying from accidents or “black-lung” disease before they reached the age of 35. Hundreds of thousands of children, some as young as six, were forced to work 12 hours a day, often being whipped or beaten.

A Canadian Royal Commission on Child Labour in the late 1800s reported that “the employment of children is extensive and on the increase. Boys under 12 work all night in the glass-works in Montreal. In the coal mines of Nova Scotia, it is common for 10-year-old boys to work a 60-hour week down in the pits.

“These children work as many hours as adults, sometimes more. They have to be in the mill or mine by 6:30 a.m., necessitating their being up at 5 for their morning meal, some having to walk several miles to their work.”

Child labor (Source: Wikispaces)

This Royal Commission found that not only were children fined for tardiness and breakages, but also that in some factories they were beaten with birch rods. Many thousands of them lost fingers, hands, even entire limbs, when caught in unguarded gears or pulleys. Many hundreds were killed. Their average life expectancy was 33.

As late as 1910 in Canada, more than 300,000 children under 12 were still being subjected to brutal working conditions. It wasn’t until the 1920s, in fact, that child labour in this country was completely stamped out.

An enterprising union organizer managed to get into a cigar factory in 1908. He found young girls being whipped if they couldn’t keep up their production quota. Many girls wound up at week’s end owing the boss money because they had more pay docked for defective cigars than they earned.

A visitor to a twine-making factory in 1907 counted nine girls at one bench alone who had lost either a finger or a thumb.

A surgeon who lived in a mill town related in his memoirs that, over a 15-year period, he had amputated over 1,000 fingers of children whose hands had been mangled when forced to oil or clean unprotected mill machines while they were still running.

Child labour defended

This callous mistreatment of working people was not only condoned, but even extolled – and not just by the business establishment. The daily newspapers of the time also defended the employers. So did the major religions. In 1888, when labour leader Daniel O’Donaghue proposed a resolution at a public meeting in Toronto calling for the abolition of child labour, all 41 clergymen who attended the meeting voted against it.

In Quebec, for many years, the Catholic Church forbade its members to join a union “under pain of grievous sin” – and many bishops and priests went so far as to deny union members a Christian burial when they died.

Blessed by the clergy, the press, and the politicians, employers considered it their God-given right to treat workers as virtual slaves. Said railroad tycoon George F. Baer,

“The interests of the labouring man will be cared for, not by the labour agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God has given control of the property rights of the country.”

In the United States, another robber baron, Frederick Townsend Martin, was even more candid. In an interview he gave to a visiting British journalist, he boasted:

“We are the rich. We own this country. And we intend to keep it by throwing all the tremendous weight of our support, our influence, our money, our purchased politicians, our public-speaking demagogues, into the fight against any legislation, any political party or platform or campaign that threatens our vested interests.”

Back to the future

Today’s big business executives are not so outspoken, at least not in public, but privately they could make the same boast. Their basic agenda is not that much different from that of their 19th-century forerunners, whom they envy and seek to emulate. And what’s really scary is that they now have amassed almost as much of the political and economic power they need to recreate the “bad old days” of the industrial robber barons.

David Rockefeller (Source: The Corbett Report)

A modern descendant of John D. Rockefeller — his great-grandson, banker David Rockefeller — put it plainly in a speech he gave back in the 1990s:

“We who run the transnational corporations are now in the driver’s seat of the global economic engine. We are setting government policies instead of watching from the sidelines.”

A long-time proponent of a corporate New World Order, David Rockefeller has also declared that:

“The supranational sovereignty of an intellectual élite and world bankers is surely preferable to the national auto-determination practised in the past.” He also said: “All we need is the right major crisis and the nations will accept the New World Order.”

Whether 9/11 or the 2008 financial crash was the major crisis Roosevelt yearned for, they have both resulted in an upsurge of corporate power. Today’s CEOs are unquestionably calling the shots, having harnessed almost all governments to their regressive agenda. The only thing they aren’t sure about is how long it will take them to obliterate the last vestiges of the hated “welfare state” and establish the neo-Victorian New World Order David Rockefeller predicted would be the ultimate corporate triumph.

Already, in many developing nations, they have brought back child labour. Conditions in most factories operated by or for the transnational corporations in Asia and parts of Latin America are not much better today than they were in North America and Europe in the 1800s. Thousands of boys and girls are being compelled to work 12 hours a day in dirty, unsafe workshops, for 40 or 50 cents an hour.

One 15-year-old girl who started working in a maquila sweatshop in Honduras when she was 13, testifying before a U.S. Senate subcommittee on child labour 20 years ago, told how she and 600 other teenaged girls were compelled to sew cotton sweaters from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., seven days a week. They were beaten by their bosses if they make a mistake, forbidden to speak to co-workers, allowed only half an hour a day for lunch, and just two visits a day to the bathroom. She was paid 38 cents an hour to make sweaters that were sold in the U.S. for $90.

This flinthearted exploitation of child labour may never be repeated in Canada, mainly because there are so many children in poorer nations who can more easily be exploited. But don’t rule out the possibility that much of our adult work force will be driven back into a modern-day version of serfdom. With our labour laws impaired and laxly enforced, with workers’ unions and bargaining rights weakened, with well-paid manufacturing jobs being replaced by low-paid part-time or temporary work, the regression of our labour force into 19th-century-style servitude is far from a dystopian fantasy.

Canadians should take a good hard look back at the age of absolute corporate power that doomed millions to dire poverty and serfdom in the late 1800s. If they did, they might be more concerned about having to relive that blighted and benighted past – and become active in the struggle to avert it.

Featured image: credits to the owner