The CIA’s “Mystery Man” in Baghdad: Salvador-Style Death Squads in Iraq

Documentary on death squads, torture, secret prisons in Iraq

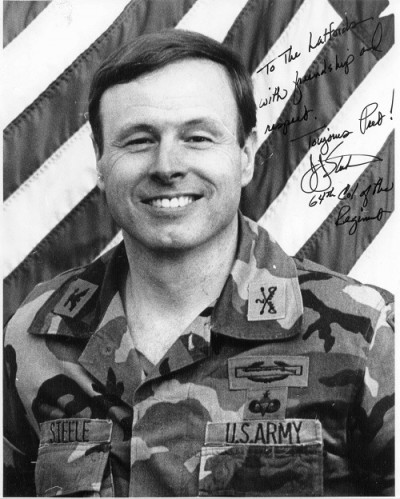

Image: Retired Col. James Steele

Official Washington has long ignored the genocide and terrorism that Ronald Reagan inflicted on Central America in the 1980s, making it easier to genuflect before the Republican presidential icon. That also helped Reagan’s “death squad” tactics resurface in Iraq last decade.

A recent British documentary Death squads, torture, secret prisons in Iraq, and General David Petraeus are among the featured atrocities in a new British documentary – “James Steele: America’s Mystery Man in Iraq” – the result of a 15-month investigation by Guardian Films and BBC Arabic, exploring war crimes long denied by the Pentagon but confirmed by thousands of military field reports made public by WikiLeaks.

The hour-long film explores the arc of American counterinsurgency brutality from Vietnam to Iraq, with stops along the way in El Salvador and Nicaragua. James Steele is now a retired U.S. colonel who first served in Vietnam as a company commander in 1968-69. He later made his reputation as a military adviser in El Salvador, where he guided ruthless Salvadoran death squads in the 1980s.

When his country called again in 2003, he came out of retirement to train Iraqi police commandos in the bloodiest techniques of counterinsurgency that evolved into that country’s Shia-Sunni civil war that at its peak killed 3,000 people a month. Steele now lives in a gated golf community in Brian, Texas, and did not respond to requests for an interview for the documentary bearing his name.

News coverage of this documentary has been largely absent in mainstream media. The Guardian had a report, naturally, at the time of release and “Democracy Now” had a longsegment on March 22 that includes an interview with veteran, award-winning reporter Maggie O’Kane, as well as several excerpts from the movie she directed. The documentary is availableonline at the Guardian and several other websites.

“James Steele” opens with a montage of soldiers, some masked, taking prisoners, some hooded, as the woman narrator sets the stage:

“This is one of the great untold stories of the Iraq War, how just over a year after the invasion, the United States funded a sectarian police commando force that set up a network of torture centers to fight the [Sunni] insurgency….

“This is also the story of James Steele, the veteran of America’s dirty war in El Salvador. He was in charge of the U.S. advisers who trained notorious Salvadoran paramilitary units to fight left-wing guerrillas. In the course of that civil war, 75,000 people died, and over a million people became refugees. Steele was chosen by the Bush administration to work with General David Petraeus to organize these paramilitary police commandos.”

Secret Prisons, Torture, Death Squads

The documentary concentrates on the creation and activities of the Iraqi police commandos who executed American policy in the face of Iraqi resistance the U.S. had never anticipated, having expected to be greeted as liberators.

There are only glancing references to the policy failures that created the crisis, such as disbanding the army and most of the government of Iraq or assuming that six U.S. police professionals would be sufficient to train a civilian police force capable of keeping peace in a nation of 30 million people.

Steele was in Iraq early in 2003 as an “energy consultant” with easy access to authorities like Gen. Petraeus, even though what he actually did in Iraq remained a mystery to most people. As the Sunni insurgency developed, Steele was brought in to organize counterinsurgency. Though still, technically, a civilian, he worked closely with Gen. Petraeus and reported directly to Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

Steele set about working with Iraqi officers to organize “special police units” under military control, as the notion of a civilian police force faded. By April 2005, there were nine battalions of these police commandos operating in Iraq, with some 5,000 in Baghdad alone.

With more and more bodies left on the streets during the night, with secret prisons spreading across the country, with reports of disappearances and torture proliferating, the New York Times took notice, at least to the extent of publishing a Sunday magazine cover story on May 1, 2005, by Peter Maass titled, “The Salvadorization of Iraq.”

By then, anyone who wanted to know the level of American-sanctioned brutality in Iraq would have had little difficulty doing so. Conditions worsened and reports kept coming throughout 2005 and 2006.

On October 2005, one of the Iraqi generals involved in the secret prisons fled Iraq and spoke out publicly from Jordan about what was happening in his country. Steele came to visit the general in Jordan, the general recalled, apparently to see if the general had any evidence – pictures, documents, tapes that could give Steele cause for concern. None have yet appeared.

Of course American media did not pursue the terror-fighting-terror story very hard, and the U.S. government denied most bad news. At a news conference on Nov. 29, 2005, a reporter asked a timid question about the killings and Secretary Rumsfeld said he had not seen any reports. Following a weak follow-up question, he said he had no data from the field – even though the truth was that Steele had reported six weeks earlier that the Shia death squads were operating effectively from his perspective.

Cold, Heartless, Ruthless, Fruitless

In the documentary, Steele is described as a cold and ruthless man by an Iraqi who knew him. “He lacks human feeling,” the Iraqi general says, “his heart has died.”

The moral vacuity of the American leadership during the Iraq War is illustrated in an exchange at a press briefing on international human rights law, in particular the treatment of prisoners, that illustrates Secretary Rumsfeld’s polite but ignorant numbness:

Gen. Peter Pace: It is absolutely the responsibility of every U.S. service member, if they see inhumane treatment being conducted, to intervene, to stop it.

Rumsfeld: But I don’t think you mean they have an obligation to physically stop it; it’s to report it.

Pace: If they are physically present when inhumane treatment is taking place, sir, they have an obligation to try to stop it.

Rumsfeld, presumably never present during inhumane treatment of a prisoner, apparently never made any effort to stop it, or to report it, or even to know about it. In that he was following the classic pattern of a cover-up as articulated by Nixon fund-raiser Maurice Stans during Watergate: “I don’t want to know, and you don’t want to know.”

The Guardian/BBC investigation into torture and death squads on Rumsfeld’s watch started after WikiLeaks provided the Guardian with almost 400,000 previously secret U.S. Army field reports, whose release is attributed to Bradley Manning. The Pentagon has not disputed the truth of the documents.

The U.S. government has arrested and tortured Manning, 25, a former intelligence officer who is currently on trial in a military court where he has pled guilty to 10 of 22 charges for which he could be sentenced to 20 years in prison. The prosecution is demanding a life sentence.

After the Stele documentary was released March 6, the Guardian invited comment from the Pentagon. Having declined to take part in the documentary as it was being made, the Pentagon said it would study the film and perhaps comment at a later date.

Unhappy with the documentary in a completely different way is Kieran Kelly whose blog critiques the movie under the headline: “The Guardian’s Death Squad Documentary May Shock and Disturb, But the Truth is Far Worse” – a claim he argues at length. For example, he criticizes the movie’s acceptance that “only” 120,000 Iraqis died in this American war, and he wonders how that “fact” squares with a million widows in Iraq?

Realistically, ten years after the American invasion, the Iraq war isn’t close to over. It’s just that, having prompted the Iraqis to kill each other the U.S. has left them to it.

[For more details on Reagan’s policies in Central America, see Consortiumnews.com’s “How Reagan Promoted Genocide.”]

William Boardman lives in Vermont, where he has produced political satire for public radio and served as a lay judge.