North American Integration and the Militarization of the Arctic

The Battle for the Arctic is part of a global military agenda of conquest and territorial control. It has been described as a New Cold War between Russia and America.

Washington’s objective is to secure territorial control, on behalf of the Anglo-American oil giants, over extensive Arctic oil and natural gas reserves. The Arctic region could hold up to 25% of the World’s oil and gas reserves, according to some estimates. (Moscow Times, 3 August 2007). These estimates are corroborated by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS): “The real possibility exists that you could have another world class petroleum province like the North Sea.” (quoted by CNNMoney.com, 25 October 2006)

From Washington’s perspective, the battle for the Arctic is part of broader global military agenda.

It is intimately related to the process of North American integration under the Security and Prosperity Partnership Agreement (SPP) and the proposed North American Union (NAU). The SPP envisages, under the auspices of a proposed “multiservice [North American] Defense Command”, the militarization of a vast territory extending from the Caribbean basin to the Canadian Arctic.

It also bears a relationship to America’s hegemonic objectives in different parts of the World including the Middle East. The underlying economic objective of US military operations is the conquest, privatization and appropriation of the World’s reserves of fossil fuel. The Arctic is no exception. The Arctic is an integral part of the “Battle for Oil”. It is one of the remaining frontiers of untapped energy reserves.

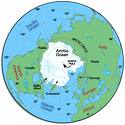

The Arctic nations (with territories North of the Arctic circle) are Russia, Canada, Denmark, the US, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Iceland. The first three countries (Russia, Canada and Denmark) possess significant territories extending northwards of the Arctic circle. (see Map).

Directed against Russia, which is in the process of claiming part of the Arctic shelf, Washington’s Arctic strategy is tied into a broader process of militarization and territorial integration.

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United States has adopted a unilateral approach to Arctic development. It has refused to approve the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which was ratified by both Russia and Canada. A United Nations Committee currently administers the Law of the Sea Convention.

The US transpolar territory is much smaller than that of Russia, Canada and Denmark. US territories bordering the Arctic are limited to the North Alaskan coastline, extending from the Bering straits to the Northeastern Alaskan US-Canadian border. The US has a number of US military bases and installations in Alaska. There are several human settlements on the Northern Slope ( Northern Alaska coastline bordering the Arctic Ocean), including Prudhoe Bay, Barrow and Cape Lisborne. This Northern Slope is rich in oil. It was among the first areas of development of Arctic oil. The Alaskan pipeline links Prudoe Bay on the North Slope to the port of Valdez in Prince William Sound on the Gulf of Alaska.

Russia

Russia, in contrast, has by far the largest border with the Arctic, from the Northwestern city of Murmansk on the Russian-Finnish border, extending over the entire Northern Siberian region, to the Bering Straits, which separate Alaska from the Russian Federation. Murmansk is the largest city north of the Arctic Circle, with a population of more than 400,000 inhabitants. In other words, a large part of the Russian Siberian continental shelf borders the Arctic.

Russia, going back to the Soviet era, had established scientific-military stations on the island of Northern Zemlya as well as in the Francois Joseph archipelago (Franz Josef Land), which is also under Russian jurisdiction. (See map.) Northern Zemlya was used during the Soviet era for underground nuclear testing.

Russia is now claiming sovereignty (under the International Convention on the Law of the Sea, UNCLOS) over a vast 1,191,000 sq km territory which is part of the Arctic shelf.

This territory claimed by Russia submitted to the UN Committee that administers UNCLOS is said to contain substantial hydrocarbon reserves, on the Arctic seabed:

The 1982 International Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) establishes a 12 mile zone for territorial waters and a larger 200 mile economic zone in which a country has exclusive drilling rights for hydrocarbon and other resources.

Russia claims that the entire swath of Arctic seabed in the triangle that ends at the North Pole belongs to Russia, but the United Nations Committee that administers the Law of the Sea Convention has so far refused to recognize Russia’s claim to the entire Arctic seabed.

In order to legally claim that Russia’s economic zone in the Arctic extends far beyond the 200 mile zone, it is necessary to present viable scientific evidence showing that the Arctic Ocean’s sea shelf to the north of Russian shores is a continuation of the Siberian continental platform. In 2001, Russia submitted documents to the UN commission on the limits of the continental shelf seeking to push Russia’s maritime borders beyond the 200 mile zone. It was rejected.

Now Russian scientists assert there is new evidence that Russia’s northern Arctic region is directly linked to the North Pole via an underwater shelf. Last week a group of Russian geologists returned from a six-week voyage to the Lomonosov Ridge, an underwater shelf in Russia’s remote eastern Arctic Ocean. They claimed the ridge was linked to Russian Federation territory, boosting Russia’s claim over the oil- and gas-rich triangle.

The latest findings are likely to prompt Russia to lodge another bid at the UN to secure its rights over the Arctic sea shelf. If no other power challenges Russia’s claim, it will likely go through unchallenged. (See Vladimir Frolov, Global Research, July 2007)

Russia is basing its claim on the grounds that this portion of the Arctic sea shelf is connected to Russia’s continental shelf, through the 2000 km long underwater Lomonosov ridge. “According to Russian media, the physical connection to the Russian intercontinental shelf means that the ridge is technically a part of Russia, and therefore open to exploitation.”

( http://www.oilmarketer.co.uk/2007/07/04/russia-seeks-un-approval-on-artic-oil-grab/

The Strategic Role of Canada and Denmark’s Arctic Territories

After Russia, Canada and Denmark have the largest transpolar territories.

To effectively challenge and encroach upon Russian territorial claims in the Arctic, Washington requires not only the collaboration of Canada and Denmark, but also jurisdiction over their respective Northern territories, which are considered by Washington as strategic from both a military and economic standpoint.

The US has a military presence in both Canada and Denmark (Greenland). Both countries play an important role in Washington’s Arctic strategy.

Canada’s territory, extends northwards to the Queen Elizabeth archipelago which includes Ellesmere Island bordering onto the Sea of Lincoln, which is part of the Arctic Ocean. Ellesmere Island is part of the Canadian territory of Nunavut.

Alert on Ellesmere Island (located at 82°28’N, 62°30’W) is considered the northernmost human settlement in the world. In practice it operates as a military intelligence station (Canadian Forces Station Alert) is under the jurisdiction of the Canadian military. CFS Alert is 840 km from the North Pole.

The militarization of the Arctic is part of the process of North American integration under the Security and Prosperity Partnership Agreement (SPP). The proposed North American Union (NAU) constitutes a means for the US to extend its sovereignty over Canada’s Arctic territories.

When the creation of US Northern Command was announced in April 2002, Canada accepted the right of the US to deploy US troops on Canadian soil, extending into its Arctic territories:

“U.S. troops could be deployed to Canada and Canadian troops could cross the border into the United States if the continent was attacked by terrorists who do not respect borders, according to an agreement announced by U.S. and Canadian officials.” (Edmunton Sun, 11 September 2002)

In April 2006, Canada formally ratified a renewed North American Aerospace Defense Agreement (NORAD), (“renewed NORAD”), which allows the US Navy and Coast Guard to deploy American war ships in Canadian territorial waters including its Arctic seabed territories. (For further details, see Michel Chossudovsky, Canada’s Sovereignty in Jeopardy: The Militarization of North America, Global Research, August 2007)

Greenland

Greenland, which is under Danish jurisdiction, constitutes a sizeable landmass bordering the Arctic Ocean.

The Thule Air Force base in Northern Greenland is under the jurisdiction of the US Air Force 821st Air Base Group. It constitutes the US’s northernmost military facility (76°32′N, 68°50′W). The military base lies approximately 1118 km north of the Arctic Circle and 1524 km south of the Terrestrial North Pole. The Thule base is 885 km east of the North Magnetic Pole.

The Thule US Air Force base also “hosts the 12th Space Warning Squadron, a Ballistic Missile Early Warning Site designed to detect and track Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) launched against North America.”

The Thule base links up to NORAD and US Northern Command headquarters at the Peterson Air Force base in Colorado. The Thule base is also “host to Detachment 3 of the 22d Space Operations Squadron, which is part of the 50th Space Wing‘s global satellite control network.”

Denmark is member of NATO, firmly allied with the US. Both Danish and Canadian territory will be used by the US to militarize the Arctic. Denmark has also been a firm supporter of the Bush administration’s military agenda in the Middle East.

Canada’s Arctic Military Facilities

Ottawa’s July 2007 decision to establish a military facility in Resolute Bay in the Northwest Passage was not intended to reassert “Canadian sovereignty. In fact quite the opposite. It was established in consultation with Washington. A deep-water port at Nanisivik, on the northern tip of Baffin Island is also envsaged.

The US administration is firmly behind the Canadian government’s decision. The latter does not “reassert Canadian sovereignty”. Quite the opposite. It is a means to eventually establish US territorial control over Canada’s entire Arctic region including its waterways.

Under the renegotiated North American Aerospace Defense Agreement (NORAD), the US military has access to Canada’s domestic territorial waters including Canada’s sea shelf with the Arctic, which coincidentally also provides Washington under the guise of “North American sovereignty” with a justification to challenge Russia in the Arctic.