Why Western Economies Are at Risk of Entering a Period of Slower Growth and Impoverishment in the Coming Years

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Donation Drive: Global Research Is Committed to the “Unspoken Truth”

***

“Economic thinking about immigration is generally quite superficial. It is a fact that in different [rich] countries, reproducible national capital is on the order of four times yearly national income. As a result, when an additional immigrant worker arrives, in order to build the necessary infrastructure (housing, hospitals, schools, universities, infrastructure of all kinds, industrial facilities, etc.), additional savings equal to four times the annual salary of this worker will be needed. If this worker arrives with a wife and three children, the additional savings required will represent, depending on the case, ten to twenty times the annul salary of this worker, which obviously represents a very heavy burden for the economy to bear.“ —Maurice Allais (1911-2010), 1988 Nobel Prize in economics, 2002.

“What is the role of the Canadian government [in regards to immigration]? If it follows the recommendations of immigration advocates, it makes policies to maximize world welfare and its goal should be high, if not unlimited immigration. If its policies are to maximize the welfare of the native (Canadian) population, immigration policies should be designed to eliminate the fiscal burden (of between $20 and $26 billion a year) so that only positive economic benefits occur through immigration.” —Hebert Grubel (1934- ), Emeritus professor of economics, Simon Fraser University, 2013.

“You cannot simultaneously have free immigration and a welfare state.” —Milton Friedman (1912-2006), Professor of Economics, University of Chicago, 1999.

*

There’s no magic in economics.

To consume, you must produce, and to produce, you must save (income minus consumption expenses) and invest in productive capital, in infrastructure and in other means of supporting production. A stock of productive capital (businesses, factories, machinery, equipment, infrastructure) is required, plus innovations, technical progress, knowledge, management, reliable sources of energy and, above all, qualified workers, capable of contributing to increasing productivity and to raising the annual output of goods and services per capita.

That is how living standards and the average person’s well-being rise in some economies and why living standards remain stagnant or increase slowly in other economies.

This is explained in some economies by the lack of savings and productive capital relative to the numbers and skills of workers as well as other factors. Indeed, other economic indicators of human development do take into account the quality of life (economic and political stability, public health, education, individual security, etc.) of a population, beyond just the average of domestic output of goods and services per capita, the latter possibly distributed in a very unequal manner.

Nowadays, the so-called ‘advanced’ Western economies are considered relatively productive and their populations enjoy a relatively high standard of living, as measured by the average gross domestic product per capita. This is essentially because their stock of productive capital is high and because they benefit from technical progress, cheap energy sources and have access to a qualified labor force.

However, such relative success is not necessarily permanent and a foreclosed conclusion, if the conditions for economic growth atrophy or are replaced by other less efficient factors. A decline in living standards is not inevitable, but it can become possible, or even likely, if public policies are poorly designed.

Indeed, there have been structural changes taken place in Western economies, over several decades now, in Europe and North America. These has been a slowdown in new productive investments, a relative expansion of the services sector, an influx of low-skilled workers resulting from illegal immigration, the adoption of energy transition policies to encourage an increased reliance on more costly and less reliable energy sources and a chaotic geopolitical environment that has enhanced the possibility of hegemonic wars.

1. A simple model to understand the sources of real economic growth in the long term

Let’s start with a simple model of the real economic growth, i.e. the Solow model.

This model states that an economy’s long-run economic output growth depends on its stock of productive capital, resulting from savings, technological progress and the supply of labor.

The higher the stock of capital available in an economy, the more abundant the yearly domestic output of goods and services will be, for a given population.

If we consider that the living standard of a population ultimately depends on the stock of accumulated capital and that the annual growth of gross domestic product (GDP) depends largely on this capital, it follows that the more workers are qualified and the more they have access to capital (businesses, factories, machinery, equipment), the more productive they are, and the higher the living standard of the entire population will be.

2. An industrialized economy relies on more capital than a less developed economy

It has been observed that for an industrialized economy, it takes an average value of about $4 of capital to generate an annual domestic output of $1, at a ratio of 4:1. In a subsistence or stagnant economy, conversely, where the living standard is low, the capital/annual production ratio is low, possibly not exceeding the ratio of 1:1.

This may explain, to a large extent, the tendency towards large-scale population migrations, originating from countries with low living standards and a high demographic growth, towards countries with high living standards and highly capitalized.

In the short- and medium-term, such a migratory phenomenon is not necessarily to the advantage of advanced economies, which may see their rate of economic growth decline and the living standard of their population fall, if enough new investments are not added to the existing stock of capital.

3. Economic growth vs. population growth

One thing to understand is the following. If the population increases in an industrialized economy, either through the natural process or through a high influx of immigrants, it is then necessary that the stock of productive capital and the infrastructures of such an economy increase also, in a ratio of 4:1, (in the absence of technological progress), so as to maintain the standard of living of the entire population.

In other words, if the level of capitalization of a country with an advanced economy does not increase in proportion, and at the same time, as a strong demographic expansion takes place, a decline in income per capita and a general lowering of the living standard can be expected.[1]

It has become trivial to say that Western economies have become consumer societies. They are economies in which the percentage of goods and services produced and consumed occupy more than sixty percent of total production.

It is a complex evolution which is linked to the phenomenon of deindustrialisation that has been observed for half a century in most Western economies. It is measured by the decline of the part of industrial added value and industrial jobs, in GDP and in total employment.[2]

Such a phenomenon is accompanied by a national relocation of certain high productivity industries towards emerging economies, under the influence of economic globalization. This has meant a relative expansion of the production and consumption of private services (commerce, finance, transport, catering, entertainment, etc.) and of public services (teaching, health care, administration, etc.), a sector generally less likely to record important productivity gains.

4. Structural dissavings of governments through debt

Relative deindustrialization and the shift to a service economy in Western economies has forced governments to increase their budgetary deficits, pushing some countries into a level of total public debt that currently exceeds the level of their gross domestic product.

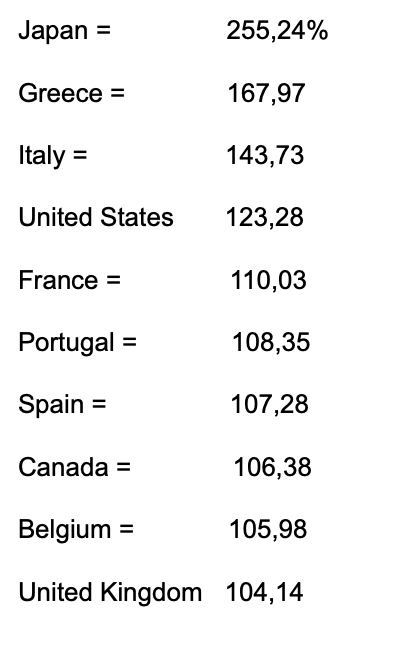

Those advanced economies with the highest levels of national debt relative to their annual gross domestic product, in 2024, as measured by the percentage of public debt to annual GDP, are:

P.S.: Japan is a special case because of its high household saving rate. Personal savings in Japan averaged 13.09% from 1963 until 2023, reaching an all time high of 62.10% in June of 2020. Moreover, Japan’s public debt is nearly all domestic.

For a more complete picture, one must add to the current public dissavings of governments the increasing waste of resources devoted to the global arms industry and to recurring ruinous and polluting wars, some of which could eventually lead to a catastrophic nuclear war.

5. Global warming and the energy crisis

There is a great complementarity between productive capital and energy. Indeed, when energy sources were abundant and could be considered unlimited, they were considered a given. Since pollution resulting from the burning of fossil fuels is one of the causes of global warming, this cannot be the case in the future.

Moreover, the global warming crisis has persuaded several governments to take drastic measures to reduce the combustion of fossil fuels, which are relatively abundant but non-renewable, easy to exploit and highly energy efficient (coal, oil, natural gas, etc.). The goal is to gradually replace them, over the coming decades, with less abundant renewable energy sources (solar, wind, hydraulic, etc.), some of which are intermittent and less reliable, in addition to being expensive to exploit.

The nuclear sector falls between these two categories of energy sources. Nuclear power accounts for about 10% of electricity generation globally. Nuclear power has advantages and disadvantages, but it is very expensive to produce. However, certain countries lacking alternative energy sources, such as France, will not have much choice but to resort more to it in the future.

6. Energy has played a big role in the rapid rise in living standards

Since the first Industrial Revolution, from 1750 to 1900 in Europe, and its acceleration in the 20th century, the availability of abundant and inexpensive energy sources of fossil fuels has been an important factor that has propelled industrial and commercial civilization upwards. Indeed, this is what has transformed economies that, for millennia, had been agrarian and artisanal, into urbanized industrial and commercial economies, like those of today.

In the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the advent of machines in the textile industry as well as in agriculture, followed by electrification and the subsequent multiplication of the means of transport, helped to multiply the physical and manual labor of workers and increase the production and distribution of products on a high scale. This resulted in considerable increases in labor productivity and in real GDP growth. GDP per capita followed, propelling upward the standard of living and the wealth of nations, as well as the quality of life of their populations.

For example, during the forty years between 1960 and 2000, a period of strong economic growth and relative international peace, French researcher Simon Yaspo estimated that GDP per capita in France, Germany and in the U.S. grew by more than 250 percent.

Such a rise has never been seen before in the history of the world. It is possible that humanity might never again experience such a long golden period of economic growth, with such a rapid rise in living standards.

7. Government policies and the energy transition

There is currently, in certain government circles, great optimism regarding the possibility of decarbonizing some national economies over the next quarter of a century, that is to say by the year 2050. This is based on the belief that substitution policies can be designed to promote a relatively rapid shift, from more polluting energies to cleaner ones. The objective is to limit the rise in global warming to 1.5℃ by the year 2050 and to keep it below 2.0℃ by the year 2100.

However, numerous economic and political obstacles could stand in the way of such an otherwise very laudable scenario.

The 2023 energy report, published by the International Energy Agency (IEA), is somewhat less hopeful that a quick reduction of fossil energies can occur before 2050. Indeed, according to the organizations’s most recent energy forecasts, global consumption of oil and natural gas, which is expected to peak during the current decade, is seen to remain more of less around that level, until the year 2050. This is a consequence of the inertia and synergy that exist in energy systems. In other words, the development of new energy sources requires the use of fossil energies.

However, IEA is optimistic about a rapid reduction in the global consumption of coal, the most available and cheapest energy source. It predicts that such a consumption, after a peak reached also during the current decade, will quickly fall by 40% by the year 2050, which could bring it back to the level observed in the year 2000.

Nevertheless, coal and charcoal wood play a major role in heating, cooking and electricity production in several emerging and developing countries. The Chinese economy alone, for example, is responsible for 50% of global coal consumption. In Africa, coal represents 70% of the continent’s total energy consumption. Some resistance to switching from coal to more costly sources of energy could be expected from these regions.

Moreover, even in Western nations, some political resistance could be expected about the negative economic effects that an imposed energy transition could have on living standards and on the quality of life of populations. Some governments, seen as being too hasty on the issue or ill-prepared to mitigate its consequences, could be overthrown and be replaced by political leaders more inclined to resort to adaptation measures rather than to simple suppression, concerning energy production and consumption of various sources of energy.

Conclusions

The Great Recession of 2007-2008 may have served as a warning sign that the sources of economic growth in Western economies were beginning to fade. That deep recession forced major central banks to push interest rates way down, even towards zero, in order to stimulate growth.

In the coming years, Western economies will have to face structural developments even riskier to their future prosperity.

Indeed, Western economies risk suffering, all at the same time, from: 1- a slowdown in productive investments and productivity gains, the results of deindustrialization and the transition to a service economy; 2- a pressure from largely under-qualified illegal immigration, which could lower the ratio of productive capital per capita and accentuate the push towards consumption of public and private services; 3- public dissaving, the result of high public budgetary deficits and a resulting public over-indebtedness; 4- a waste of resources due to the expansion of the unproductive arms sector, in a global context of geopolitical instability and wars; and, 5- an energy transition that will be difficult to achieve, with policies aimed at penalizing inexpensive fossil fuels, in favor of more costly and less reliable alternative energies.

With these economic headwinds interacting and reinforcing each other, western economies could face lower economic growth rates ahead. This could also translate into a relative drop in standards of living, and also possibly, in people’s quality of life, over the coming years and coming decades.

In fact, in a not too far away future, the main limiting factor to economic growth in Western economies could likely come from more expensive sources of energy, which are less reliable than in the past. Likewise, demographic growth rates that are too rapid in relation to the stock of available productive capital, the result of uncontrolled immigration, could also become a cause of economic impoverishment.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

This article was originally published on the author’s blog site, Dr. Rodrigue Tremblay.

International economist Dr. Rodrigue Tremblay is the author of the book about morals “The code for Global Ethics, Ten Humanist Principles” of the book about geopolitics “The New American Empire“, and the recent book, in French, “La régression tranquille du Québec, 1980-2018“. He was Minister of Trade and Industry (1976-79) in the Lévesque government. He holds a Ph.D. in international finance from Stanford University. Please visit Dr Tremblay’s site or email to a friend here.

Prof. Rodrigue Tremblay is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Notes

1. The decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire, in the 5th century AD, is probably the most complex and most important historical phenomenon of an economic, political and military system that collapsed under the effect of several causes, but notably following a fall in income.

2. For example, the share of industrial jobs in total employment dropped by more than half in advanced economies, from 1970 to 2016.

The share of industrial jobs in total employment went from 46% to 17% in the U.K., from 31% to 17% in the U.S., from 39% to 18% in France, from 45% to 17% in Belgium. In Canada, the share of manufacturing jobs in total employment fell from 19.1% to 9.1%, from 1976 to 2019.

(For Quebec and Ontario, during the same period, the share of manufacturing employment, in total provincial employment, dropped from 23.2% to 11.5%, in the first case, and 23.2% to 10.2%, in the second case.

The Code for Global Ethics: Ten Humanist Principles

The Code for Global Ethics: Ten Humanist Principles

by

Publisher: Prometheus (April 27, 2010)

Hardcover: 300 pages

ISBN-10: 1616141727

ISBN-13: 978-1616141721

Humanists have long contended that morality is a strictly human concern and should be independent of religious creeds and dogma. This principle was clearly articulated in the two Humanist Manifestos issued in the mid-twentieth century and in Humanist Manifesto 2000, which appeared at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Now this code for global ethics further elaborates ten humanist principles designed for a world community that is growing ever closer together. In the face of the obvious challenges to international stability-from nuclear proliferation, environmental degradation, economic turmoil, and reactionary and sometimes violent religious movements-a code based on the “natural dignity and inherent worth of all human beings” is needed more than ever. In separate chapters the author delves into the issues surrounding these ten humanist principles: preserving individual dignity and equality, respecting life and property, tolerance, sharing, preventing domination of others, eliminating superstition, conserving the natural environment, resolving differences cooperatively without resort to violence or war, political and economic democracy, and providing for universal education. This forward-looking, optimistic, and eminently reasonable discussion of humanist ideals makes an important contribution to laying the foundations for a just and peaceable global community.