Western Allies Terror-bombed 70 German Cities by 1945

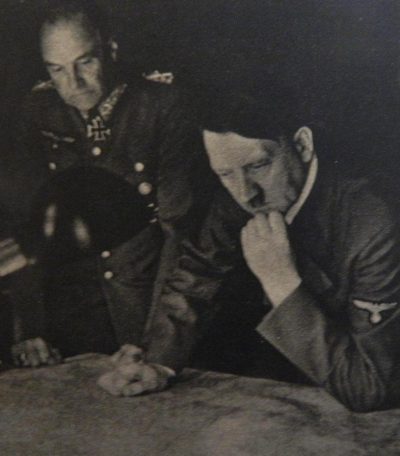

During late November 1944, the German armaments minister Albert Speer met with his leader, Adolf Hitler, at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin so as to debate the ongoing war effort. Much to Hitler’s incredulity, Speer had been overseeing what seemed like miracles for months on end.

In late 1944 German production of panzers, aircraft and munitions reached an all-time high, in spite of the now almost unchallenged Allied aerial attacks.

While Speer and Hitler convened for discussions, the Nazi leader gestured outside towards the ruins of Berlin. Hitler turned and said jokingly,

“What does all that signify, Speer? In Berlin alone you would have to tear down 80,000 buildings to complete our new building plan. Unfortunately, the English haven’t carried out this work exactly in accordance with your plans, but at least they have launched the project”.

Hitler was in fact shaken by the devastation meted out upon the Reich by British and American aircraft – but what maintained his spirits during the war’s late stages was the great assault he was preparing to unleash mostly through Belgium: The Ardennes Offensive, which would send Allied armies careering back into the English Channel.

The Ardennes itself – with its vast woodlands, rolling valleys and winding rivers – was a magical, mystical place for Hitler, and one he long associated with his crushing victory over France more than four years before; as the panzers and armoured vehicles somehow carved a path through the Ardennes’ “impenetrable” forests. It was no coincidence that in this dense, misty terrain, the dictator would launch a second major land incursion.

The Ardennes Offensive, beginning in December 1944, would not have been possible had Allied leaders directed their pilots more regularly towards bombardment of German industrial plants, communication signals and transportation lines.

Instead, from 1940 British and later American airmen were ordered to implement “area bombing”; in plain English, the destruction of cities and residential areas which entailed, as was known, the deaths of noncombatants like women, children, along with the elderly. This was a particular brand of Anglo-Saxon warfare, which had prior agreement in the highest levels of Allied government circles.

Shortly after becoming Britain’s prime minister in May 1940, Winston Churchill had said,

“this war is not against Hitler or National Socialism, but against the strength of the German people, which is to be smashed once and for all, regardless of whether it is in the hands of Hitler or a Jesuit priest”.

By the spring of 1945, Allied aircraft had terror-bombed a remarkable 70 cities across Germany – killing around 600,000 of the Reich’s civilians, the majority of whom were mothers and children, coupled with those too old to fight – along with destroying countless hospitals, schools and historical buildings. In contrast, the Luftwaffe’s Blitz of Britain killed less than 10% of the above total, about 40,000 people.

Of the 70 German cities firebombed, 69 of them endured the obliteration of 50% or more of their urban areas.

Civilians were indeed largely targeted. Over the war’s duration, more than 2.6 million tons of bombs were dropped on Germany or Reich-occupied territory; of this, less than 2% of the total bomb outlay fell upon the Nazis’ war-making factories. The vast majority of the rest were dumped over densely populated quarters and workers’ homes, separately killing large numbers of downtrodden POWs.

The Western media strongly backed the firestorming of German and Japanese cities, even demanding “more bombing of civilian targets”, whilst criticizing the few attacks restricted to military and industrial zones.

In Europe these actions were sometimes justified by claiming that every German was a supporter of Hitler, and therefore deserved their fate. Conveniently forgotten was that Hitler received little more than a third (36.8%) of the popular vote in the spring 1932 presidential elections; while Paul von Hindenburg took home more than half (53%) of all votes. In the July 1932 federal elections the Nazi Party, though now the largest in Germany, still fell far short of a majority, as they claimed just over a third (37%) of the entire vote – and Hitler’s support actually declined slightly to 33% in the November 1932 federal elections.

Later, the desire to smash “the strength of the German people” mostly spared the Nazis’ crucial weapons factories, rail networks and other resource lines. It was a great delusion on the part of Western political and military figureheads, to believe that hitting general populations would bring the enemy to their knees.

As Hermann Goering’s 1940-41 Blitz bore proof of, unloading bombs over heavily populated regions did nothing to break a people’s morale, but in fact bolstered a nation’s resolve. When relatives or friends are killed by enemy shells, the natural human reaction is to seek revenge, while the hardship brings people together.

Unlike British and American statesmen, Hitler recognized not long after the Blitz that aerial demolition of cities would not wreck the endurance of foreign populaces. During November 1944 Hitler was again telling Speer that,

“These air raids don’t both me. I only laugh at them. The less the population has to lose, the more fanatically it will fight. We’ve seen that with the English you know, and even with the Russians. One who has lost everything has to win everything… People fight fanatically only when they have the war at their own front doors. That’s how people are”.

Three months later, at the February 1945 Yalta Conference in the Crimea, Churchill was formulating the massive attack on Dresden with his advisers. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was terribly ill at this stage but he agreed at Yalta to pinpointing Dresden, in which over 500 American heavy bombers would partake, supported by smaller aircraft.

Dresden after the bombing raid (CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

As proceedings at Yalta concluded on 11 February 1945, the firestorming of Dresden began two days later against a city whose population had swollen to over one million people, including 400,000 refugees.

Today, it is still unknown how many innocents were killed, with numbers ranging from 100,000 dead up to an extravagant half a million. Hundreds of evacuee children lost their lives, while scores of American Mustang fighter-bombers returned to mow down beleaguered survivors crowding alongside river banks and in gardens. Compounding these war crimes, Dresden contained no significant armament facilities and was an undefended university town.

While Hitler was particularly brutal in the genocide he pursued primarily against Jewish populations, he was not a proponent of systematic annihilation of urbanized places – euphemistically titled “strategic bombing”. He had not prepared for it. Throughout the war, the Germans had no possession at all of four-engine heavy bomber aircraft.

Little known, and of some importance, is that the Luftwaffe’s Blitz of Britain came as a direct response to British aerial attacks over German cities. Initially, Hitler had issued strict orders that no bombs be released on London.

Liverpool city centre after heavy bombing (Public Domain)

RAF planes pounded Berlin almost every night from 25 August 1940 until 7 September 1940, the latter date heralding the Blitz’s commencement in riposte to British targeting of German populated regions. There can be little doubt that Britain started the air war against populated centres, and in fact London’s bombers had first attacked Berlin on 15 May 1940, during the Battle of France.

People in London look at a map illustrating how the RAF is striking back at Germany during 1940 (Public Domain)

For years before Hitler had come to power, influential Britons were espousing the dropping of bombs over civilian targets – dating to such men as Lord Hugh Trenchard, England’s esteemed First World War air commander and military strategist.

As far back as 1916, Lord Trenchard was expounding that, “The moral effect produced by a hostile aeroplane… is out of proportion to the damage it can inflict”. The following year, 1917, he pleaded with Britain’s War Cabinet in allowing him to “attack the industrial centres of Germany”; and in 1918 dozens of tons of British bombs were raining down from the skies over German cities, from Cologne to Stuttgart.

In May 1941, Lord Trenchard outlined to Churchill that the German achilles heel “is the morale of her civilian population under air attacks” and “it is at this weak point that we should strike again and again”.

Two months later, July 1941, Churchill told Roosevelt that “we must subject Germany and Italy to a ceaseless and ever-growing bombardment”. Roosevelt presumably agreed with this assertion, as the US president had reacted positively when hearing plans in November 1940 regarding proposed American firebombing attacks on Japan.

By the early 1940s, fascist Italy fell out of favour in Washington and London. Yet during the 1930s Roosevelt had been quite supportive of Benito Mussolini’s regime, with the new US leader writing in June 1933 that he was “deeply impressed by what he [Mussolini] has accomplished”, describing him as “that admirable Italian gentleman”.

The British and American capitalist business communities were generally benevolent to both Mussolini and Hitler, investing significant sums in the dictatorial states, and viewing them as bulwarks against Bolshevism.

US General Billy Mitchell, an instrumental figure often dubbed “the father of the American air force”, was an ingrained exponent of mass raids over city environments. In 1932, Mitchell wrote in an article relating to Japan that,

“These towns, built largely of wood and paper, form the greatest aerial targets the world has ever seen”.

Also keen supporters of attacking built-up centres were Cordell Hull, Roosevelt’s Secretary of State, and General George Marshall, the US Army Chief of Staff.

One need but glance at the array of four-engine heavy bombers dominating the British and American fleets: Such as London’s Short Stirling (introduced August 1940), the Handley Page Halifax (introduced November 1940) and Avro Lancaster (introduced February 1942); along with Washington’s Boeing B-17 (introduced April 1938) and the B-24 Liberator (introduced March 1941). These airplanes were undergoing design long before Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, or indeed Japan’s December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

The above aircraft boasted flying ranges of over a thousand miles upwards past two thousand miles; while the Luftwaffe’s most widely known airplane, the one-engine Stuka divebomber, held a roaming distance of just 200 miles. Allied aircraft could fly far and wide so as to inflict widespread damage over concrete landscapes; while they were not created as such to aim at specific military installations or war-making facilities.

Britain’s Stirling and Lancaster bombers were designed to carry over 6,000 kilograms (14,000 pounds) of explosives, compared to the Stuka’s 700 kilograms (1,500 pounds). The Stuka’s most infamous feature was its howling, melancholic siren, which was personally devised by Hitler in order to induce maximum psychological damage on civilians, but not so much physical harm.

The aerial bombardment of German, and Japanese cities, had served to lengthen World War II by many, many months – as the raids often spared not merely industrial hotspots, but also enemy soldiers. The running joke was that the safest place to be is at the front.

Speer outlined, “The war would largely have been decided in 1943” if enemy aircraft “had concentrated on the centres of armaments production”. Yet in their bloodlust, the Allied commanders did not relent in their desire to decimate civilian areas.

Nazi Germany’s ball bearing and fuel depots, pivotal to various armaments in her war machine, were bombed sporadically at times and not at all mostly. From spring 1944, intermittent Allied air raids upon the ball bearing industry abruptly stopped.

Speer remarked that, “the Allies threw away success when it was already in their hands” while “Hitler’s credo that the impossible could be made possible” looked to be running true to form. “You’ll straighten all that out again” the Nazi leader assured Speer when war production was briefly reduced, and as the latter noted, “In fact Hitler was right – we straightened it out again”. Armaments manufacturing remained strong, giving Hitler hope that the German ability to recover from seemingly desperate predicaments could yet turn the war around.

As a consequence of the Allied fixation on turning populated centres into rubble, almost to the end of the war German construction of heavy armour and ammunition rose. Speer revealed “our astonishment” as the enemy “once again ceased his attacks on the ball bearing industry”.

Perhaps it was not as astonishing as it appeared. On 28 July 1942 Arthur “Bomber” Harris, leader of RAF Bomber Command, said that his pilots were bombing one German city after another “in order to make it impossible for her to go on with the war. That is our object; we shall pursue it relentlessly”.

Such was Harris’ desire to wreak vengeance on civilians that he opposed the introduction of other aircraft – like the RAF’s Pathfinder – that could have significantly improved precision of aerial assaults, potentially shifting Bomber Command’s focus towards military-related targets. Harris feared that the Pathfinder, introduced in the autumn of 1942, would lead to calls for an end to terror-bombing of cities, his specialty.

Harris portrayed the firestorming of Hamburg in July 1943 as “a relatively humane method”; raids which killed tens of thousands of people, mostly civilians.

The Western democracies and “defenders of civilization” – in opposition to fascist tyranny – pursued the most destructive and crude of methods in a supposed bid to quickly win the war.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree. He is interested in writing primarily on foreign affairs, having been inspired by authors like Noam Chomsky. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.