The War on Journalists and Environmental Defenders in the Amazon Continues

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Since I became an environmental journalist six years ago, my family, friends and acquaintances all labeled me “crazy”. Why? Because they were extremely scared after reading my articles and hearing my testimonies of field investigative reporting experiences in the Brazilian Amazon.

The question that I have always heard since then was: “Aren’t you afraid of the work you do?” Until June 5, I’ve automatically responded: “No.”

But now I am afraid. And ravaged, angry, and sad.

Journalists in Brazil and around the world are devastated — and scared — about the tragic end of a 10-day search for British journalist Dom Phillips and Indigenous advocate Bruno Pereira in the Amazon rainforest near the Brazil-Peru border in northern Amazonas state. Bodies believed to be theirs were found on June 15 after a huge outcry against the federal government’s inaction following their disappearance. Indigenous patrols bravely conducted their own search while the government did little.

Vigil for Dom Phillips and Bruno Araújo Pereira at the Brazilian Embassy in London. Image courtesy of Chris J Ratcliffe/Greenpeace

Dom and Bruno had gone missing June 5 as they returned from a visit to Indigenous territory in the Javari River Valley, where about 6,000 Indigenous people live, including some of the last groups living in voluntary isolation from the outside world. This area has lately become known as one of the “most dangerous” in Brazil due to the onslaught of violence against Indigenous peoples by illegal land invaders, drug traffickers, miners, loggers, and fishermen.

I was completely shocked when I read the news about their disappearance on June 6. Within minutes, I started receiving dozens of messages from caring friends. “Do you know them, Karla?” “I worry about you, my friend” “When I read this news, I froze thinking about you!” “I’m so glad you’re in Rio, well and safe!”

A movie started to play in my mind with several risky situations where I put myself while reporting in the Amazon. The very first happened five years ago, when a Canadian journalist and myself went in a boat with garimpeiros (gold miners) in the Madeira River, in northern Rondônia state, visiting barges and dredges for a story about illegal gold mining. In early 2019, an English documentary filmmaker and myself heard shots on our way back from field reporting in the Arariboia Indigenous Reserve, in northeastern Maranhão state, considered one of the most threatened Indigenous territories. At the end of that same year, two motorbikes followed me and my reporting team on our way back from the Tembé Indigenous Reserve, in northern Pará state, where I was doing a palm oil investigation. These are but a few personal experiences — I’ve heard many similar accounts from fellow reporters, photographers, and filmmakers.

From that moment, a thought stuck in my head: “What happened to Dom and Bruno could have happened to any of us.”

Aerial view of the Javari River in Brazil’s northern Amazonas state. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

Since that day, I haven’t been sleeping well. I’ve been waking up in the middle of the night and thinking about Dom and Bruno, as well as about the future of environmental reporting.

I knew Dom and Bruno, who were admired for their work. Dom was one of the first international correspondents I met in Rio, when I started working for foreign media and started going to a monthly happy hour of correspondents based in the city. He was always very nice and was an intriguing and engaging person to speak with.

I met Bruno in Brasília in early 2019, when he was the head of isolated Indigenous groups at FUNAI, Brazil’s Indigenous affairs agency. At the time, I was co-directing and co-producing a documentary film about the Guardians of the Forest, a group of Guajajara Indigenous who risk their lives to protect their Arariboia reserve against illegal loggers and also to protect the Awá isolated Indigenous people who live in the same territory. Dom did a great story about the Guardians in 2015 and I remember him congratulating me about the documentary film, which won three international awards.

In November 2019, Paulo Paulino Guajajara, one of the Guardians featured in the documentary film, was brutally murdered in the Arariboia reserve, allegedly by illegal loggers. I remember as if it was today how devastated I was for several months, sleepless as I thought about Paulo and his family as well as Laércio Guajajara, the Guardian who escaped the ambush. Nobody has been charged yet for these crimes.

Three years later, Bruno is the second interviewee featured in the documentary film who was murdered. And he was very connected to Dom, who also reported about the Guardians. This only came to my mind now, as I write. I now see a tragic connection between the three murders: they were all warriors and Guardians of the Forest.

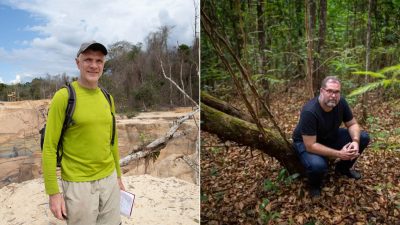

The murders of British journalist Dom Phillips (left) and Indigenous advocate Bruno Pereira (right) in the Brazilian Amazon are emblematic of the plight of journalists and activists across Latin America as violence escalates in the region. Composite: João Laet/AFP/Getty Images (left); Daniel Marenco/Agência O Globo (right).

The murders of Dom, Bruno, and Paulo are emblematic of the plight of journalists across Latin America as violence against both journalists and activists in the region escalates. It also raises an alarm for the need to protect reporters as we report on environmental crime from Nature’s frontline.

But these crimes will not stop us: Exposing wrongdoing across Brazil’s critical biomes — from the Mata Atlantica to the Cerrado to the Amazon — is more necessary than ever now. Yet after these murders, doing our jobs will be harder than ever before: Beyond the impunity with which these murderers act, it’s likely that most news outlets will set up stricter risk assessments for field reporting to protect staff and freelancers.

At the same time, demanding justice for the murder of Bruno and Dom became a fight of all of us. That’s why Mongabay signed a letter to the Brazilian government, along with dozens of media outlets, demanding immediate action to find Bruno and Dom on June 8.

Defending the Amazon and the environment is not “an adventure”, as argued by President Jair Bolsonaro in his first remarks about the disappearance of Bruno and Dom. Being an environmental journalist is a mission: A fight for a better world for future generations.

Our battle is not only for the planet — it’s also to honor the memory of all who have fallen before us, putting their lives on the line. Even as they navigated what must be unbearable grief, Alessandra Sampaio and Beatriz Matos, Dom’s and Bruno’s wives, respectively, eloquently articulated what’s at stake.

“Today, we also begin our quest for justice. I hope that the investigations exhaust all possibilities and bring definitive answers on all relevant details as soon as possible,” said Alessandra Sampaio, Dom’s wife in a statement. “We will only have peace when the necessary measures are taken so that tragedies like this never happen again.”

“Now that Bruno’s spirits are passing through the forest and spreading among us, our force is much stronger,” said Beatriz Matos, Bruno’s wife in a tweet.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.