Venezuelan Farmers Fight Monsanto Seed ‘Imperialism’ – And Win!

In this historic victory–arguably the biggest thing to happen in Venezuela since the death of Hugo Chavez–a movement of small farmers took on one of the largest corporations in the world, and won.

“Nature will always prevail,” says Angel Moreno, a campesino and leader in the National Network of Popular Agroecological Schools, as he points to the grass sprouting through the sidewalk in the mountain village of Monte Carmelo in Venezuela. “But if we’re going to fight imperialism, we need seeds.”

It is Oct. 29, 2015, the 10th anniversary of the Day of the Campesino seed, and over a thousand people from around the country and around the world have gathered in this humble village, described by the Agujero Negro media collective as “the ecosocialist capital of Venezuela.”

The people of Monte Carmelo began these gatherings in 2005, and in 2012 they hosted an international gathering from eight countries throughout Latin America. There, over multiple days of discussions and debates, they wrote the Monte Carmelo Declaration and launched the international network of the Guardians of Seeds.

Monte Carmelo has become a center of gravity in Venezuela for the politics and practice of a movement that calls itself ecosocialist, leading a return to the land and the transcendence of the oil economy. Most big decisions in Venezuela are decided in the capital city of Caracas, but the people of Monte Carmelo and the neighboring towns are leading the way in a movement which is all at once local, national and global–to return to the source of ancestral practices of seed saving.

This year the small farmers of Monte Carmelo once again took the lead in a struggle to fight back against the ongoing economic crisis through a program of grassroots action. “We’re in a profound food crisis globally,” said Ximena Gonzalez, an activist academic from the Venezuelan Institute of Scientific Investigations who like many others come to Monte Carmelo to participate and accompany this movement of seed savers. “We should take advantage of this conjuncture to put forward an integral plan of mobilization, legislation, and production.” And over the next several days, that is what happened.

The Guardians of Seeds

We live in a world where one third of all food is wasted, where industrial agriculture accounts for the lion’s share of carbon emissions, and where the genetic diversity of the whole food chain is in free-fall, all presided over by an international regime of biopiracy headed by multinational corporations like Monsanto. But not everyone is taking it sitting down.

The Guardians of the Seeds are the alternative, and in their struggles and celebrations they prefigure a different way of life. As over a thousand people streamed into the small town of Monte Carmelo on the morning of October 29, this vision comes to life. People from around the country bring their seeds to trade, to discuss, to learn and compare. Small children run through the crowds, as eager to trade for a new kind of seed as children in the cities to buy a new plastic toy.

The Guardians of the Seeds don’t see their job as just agriculture or production. There is a profound spiritual consciousness, diverse and deep, which pervades the atmosphere. “Seeds are the beginning, the force of rebirth, and the inspiration to reclaim our cultural and ancestral heritage,” said Cesar David Escalona, a young anthropologist and historian living in and studying the history of Monte Carmelo.

The Guardians are promoting not only another kind of agriculture, but another kind of life. “I used to live by earning money,” Daniel, a campesino from Trujillo told me. “Money puts your mind to sleep. True liberty is in the land, in protecting nature.”

The political framework for this vision is ecosocialism, since 2013 the official policy of the Venezuelan government. The “eco-socialist economic production model” as defined in the current six year plan, written by constituent assemblies and voted into law in 2013, is “based on a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature that guarantees the rational and optimal use of natural resources while preserving the processes and cycles of nature.” While there are ecosocialist organizations on every populated continent, each bringing the theory into unique practices, it is in places like Monte Carmelo that the political philosophy comes to life. Asking attendees what ecosocialism means to them elicits responses as diverse as the seeds themselves.

The people of Monte Carmelo are overwhelmingly in support of the current government of Venezuela, which since the election of Hugo Chavez in 1999 has transformed the country legally, socially and politically. But the vision of ecosocialism which emerges from Monte Carmelo is decidedly and unapologetically grassroots. Like in the Zapatista communities of Chiapas, in Monte Carmelo the people command and the government obeys. “Those who work in institutions don’t follow the lunar calendar,” said Angel Moreno, criticizing politicians, bureaucrats and academics who don’t work the land themselves. “We’re talking about the afro-descendent, Indigenous and campesino seeds, and we have to take care of them ourselves, so that the institutions don’t come and put our seeds in a refrigerator.” This is the Venezuelan revolution at its most radical. And it comes not a moment too soon.

Economic Crisis

Venezuela is currently in a severe economic crisis – so severe that the word that is used in Venezuela today is not crisis, but war. And it’s no exaggeration – the scale of the crisis requires the permanent mobilization of the whole society in order to make ends meet.

But in Monte Carmelo, another picture emerges of this crisis, one which again prompts us to return to the source for answers. “The economic crisis hasn’t effected us very much,” said Abigail Garcia, one of the founders of the Socialist Seedbed of Monte Carmelo: “We grow our own food; we don’t need to wait in line for mayonnaise. Most of all this crisis has provoked a change of consciousness, and that is the most important of all changes.”

All around Venezuela, this sentiment is on the front lines. As prices surge beyond control or comprehension, the economic war has also brought communities together into networks of solidarity and production, where people are rediscovering their roots.

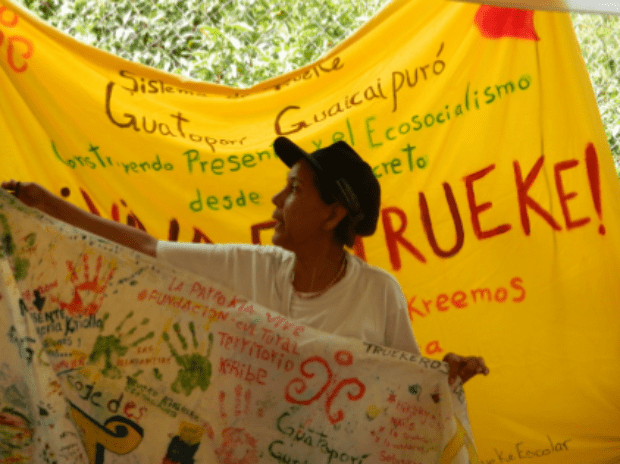

“When a crisis comes, we fall back on our cultural, historical reserves as a people, including the actual geographic sites of exchange and trade routes,” said Livio Rangel from the National Trueke Network: “We’re not talking about anything new. Look in your roots and your ancestors.” Rangel is one of the promoters of the “Trueke” movement. Literally translated as barter, Trueke combines community organizing around basic economic needs with a political and historical education wherein communities design their own currencies and organize themselves in assembly. At a Trueke, people of all ages gather to exchange everything from seeds to books, clothing to cosmetics, and also give workshops in specific skills.

“Trueke is what can save us from this economic war,” Rangel continues: “It can help us to find ourselves within our socio-productive essence…When you go to the supermarket, the Other is the enemy. When you go to Trueke, the Other is a friend, a love…” In Monte Carmelo, at the height of an economic war whose casualties are measured not only by inflation but by real human lives, where people die because medicine is being hoarded, the Trueke movement suddenly seems to have become common sense.

Trueke

The economic crisis has moved Trueke to center stage of the political process, and in Monte Carmelo this common sense is common practice: People were exchanging seeds, plants, food, books, arts and crafts, ideas and practices, all without money. I spoke with Walterio Lanz, a nationally respected figure whose innovative fish-farming practices and political activism over decades have earned him strong ecosocialist credentials. “We have gone a step beyond Jesus; we don’t just teach people how to fish, we teach them how to grow and care for them.”

While the market system is failing, this ancient system of economics is being jump-started again. The economy of Trueke reaches back to ancestral and indigenous traditions where different ethnicities engaged in trade across and throughout bioregions. An initiative from the Ministry of Higher Education has organized workshops around the country, organized by bioegion, to implement community-university Trueke systems in every state of Venezuela. And in the context of economic crisis, Trueke is taking on the character of a street action.

In the town of Lagunillas, a few days before the gathering in Monte Carmelo, I attended a Trueke where seeds were given away in exchange for the commitment to plant them (with names and phone numbers collected to check in), and dozens gathered at a workshop to learn how to make soap out of used cooking oil. “This is the ancient and new call of Trueke,” said Pablo Mayayo, another leader in the national Trueke network: “Against the monotheism of money, which we worship every day, let’s learn to resolve our problems without money. Let’s take a rest from cash, and exchange with solidarity. We are re-learning how to grow food, we are apprentices to small farmers. The return to the small farm is the return to our roots. They want this revolutionary process to fall, but what’s falling is capitalism, because it doesn’t know how to sow seeds, it doesn’t know how to love.”

Trueke is not only grassroots economics, but also grassroots democracy; an assembly at the end of every Trueke determines how to move forward; where the next one will be, who will participate, who will take which responsibilities. While hundreds of people line up in the cities to buy soap, in the countryside a new economics and a new politics are taking place. “I think that’s the most subversive thing you can do,” Livio Rangel told me: “Make your own soap, grow your own food. Make by yourself the things thatthey are hoarding. That’s the counter-model.”

Monsanto Vs. Monte Carmelo

But how does this economy and politics take on a larger scale? How can the experience of Monte Carmelo be spread and shared throughout Venezuela in the context of a rentier petroleum economy that imports the majority of its food? And how can it be mobilized to fight against the spread of corporate industrial agriculture, which has already begun to bring the chemical pesticides, fertilizers and hybrid and genetically modified seeds into the country?

In 2013, a seed law that would have opened a legal loophole for the importation of genetically modified seeds almost passed the Venezuelan legislature. Since the constituent assembly in 1999 when Venezuelans rewrote their constitution, the Venezuelan people have taken an active and leading role in writing and refining new laws to support their movements. So in 2013, the movement was ready – it blocked the passage of this law, and began a three-year process of writing a new seed law. This one would be written from the bottom up, through assemblies and workshops held across the country.

The struggle for a new seed law was the subtext of this year’s gathering in Monte Carmelo. With parliamentary elections coming up that December, it was widely perceived that the movement needed to act quickly to pass the People’s Seed Law, which by October had achieved consensus in assemblies throughout the country.

Tensions were high. One woman in an assembly reminded the crowd: “If the bad seed law is approved, we will all be converted into criminals – everyone who grows and guards ancestral seeds.” As far-fetched as it sounds, laws have criminalized seed saving around the world. The United States is an instructive example, where the federal government has persecuted and shut down seed banks across the country.

So in the midst of debates on October 30, the assembly decided that they would convoke a march to Caracas where they would rally outside the national assembly and demand that the people’s seed law be passed. And so it was. At the end of November, the outgoing national assembly voted into law a revolutionary seed law written by small farmers. It outlaws not only any GMO seeds, but also prohibits all forms of patent and intellectual property rights on seeds. And because small farmers know that laws on paper by themselves don’t necessarily change things, the law also stipulates that the government is responsible for helping to promote an alternative sustainable agro-ecological model throughout the country.

In this historic victory – arguably the biggest thing to happen in Venezuela since the death of Hugo Chavez – a movement of small farmers took on one of the largest corporations in the world, and won. And yet they remain humble. “We’re not at the head or the first of anything, we’re not on the top of a pyramid,” said Alan Soto Lopez, an artisan and activist who accompanies this movement. Walterio Lanz echoed: “We’re just doing what history is pushing us towards.”

“Plan de Siembra”

Even before the passage of the revolutionary seed law, the Guardians of the Seeds were dreaming up plans for how to organize the country along ecosocialist lines. On October 30, after the Day of the Campesino Seed, a coalition of academics and farmers, young activists and veteran organizers gathered in Monte Carmelo to debate a plan to win the economic war by building an ecosocialist mode of production from the bottom up; the “Plan de Siembra,” or the Plan of Sowing.

“Where are we going?” a poster at the front of the room asked at the beginning of a long day of discussion and debate, and pointed towards the answers: “Toward productive and political coherence: the rescue of native varieties, the use of organic fertilizers, and the empowerment of a communal chain of production and distribution.” The plan, which was subsequently illustrated and refined throughout the day, was to sow over 60,000 acres under “the logic of the communes.” Forty thousand would be devoted to corn, to beat the monopoly on pre-cooked corn flour owned by the Polar company, directed by the counter-revolutionary agribusiness tycoon Lorenzo Mendoza.

While Monsanto and other proponents of the Green Revolution propose that societies like Venezuela overcome their food problems by turning to new innovations in agricultural science and technology, the Guardians of the Seeds and their allies in Monte Carmelo are pointing in precisely the opposite direction.

“The ancient things are the most powerful,” Mayayo explained: “They are more trustworthy than the new things, because the ancient things have already proved themselves; they have resisted capitalism for hundreds of years. They’re still here!”

For the whole day, the hundreds of people from around the country divided themselves into rooms organized by type of crop – beans, corn, potatoes, and so on – in order to measure the efforts of all the different communities and integrate them into a coherent whole.

Here in a small mountain village, small farmers were on the cutting edge of history, protagonists in debates concerning the future of the nation and the revolutionary process.

Gabriel Garcia, a small farmer and a leader in Monte Carmelo, emphasized that there should not be a centralized state bureaucracy which manages seeds, and that legislation should not substitute for mobilization: “Seeds can’t be in a museum. They have to be cultivated. Every day is the Day of Seeds, not just October 29. We have to believe in ourselves, or we’ll always depend on technicians from universities, and we’ll end up using heavy machinery and other inappropriate technologies.”

Rangel and Mayayo from the Trueke network voiced concerns that the Plan of Sowing should not devolve into centralized bureaucracies where small farmers would be once again sacrificed on the altar of industrial production. “First they kick the small farmer off the land, then they force them into a city, and now they want to accuse them of not producing enough to feed the city?” Rangel questioned: “The point is not just the seed but the farmer; to defend not just the seed but the person who defends the seed. In counting seeds we get screwed. Take the harvest to the Trueke, not to the state.” Angel Moreno also argued against the quantitative framework: “Here in this seed is our essence. It can’t be measured.” Mayayo continued, “central planning in agriculture never worked in Russia or in China. It worked in health, education, prevention of accidents, but not in economy.” Walter Lanz took it a step further, telling me later: “any solution has to break with the logic of cities. As long as we can’t break from the model of exploiting the country to feed the city, we’ll never resolve our social or ecological problems.”

Such radical and often spiritual perspectives are strong in Monte Carmelo, and the tensions between small farmers who insist that their production could not be measured clashed with those who were concerned that without a quantifiable plan, the movement would not be able to either pass legislation that favored their efforts, or truly coordinate them into a coherent whole capable of providing an alternative to both the current economic crisis or the industrial agriculture of the Green Revolution. The debates were not only between friends and comrades and organizations, but also included deputies and representatives of the government.

And yet what emerged was not a mess of contradictions, but a beautifully complex picture of solidarity and struggle. Relieving some of the high tensions after a day of debates, Moreno reminded everyone that they were together as revolutionaries. “We live conspiring. We have to be insurgents. Next year let’s come with sacks of seeds, not just little bags.”

Conclusion

The Guardians of Seeds in Monte Carmelo are returning to the source, and they are inviting the world to join them. Their program is an integrated plan of action, including mobilization, legislation, and production. It’s an uphill battle in difficult conditions, but their convictions, like their practices, are deeply rooted and not easily discouraged.

An international media and diplomacy war against Venezuela continues to confuse the world about what is really happening in Venezuela – to the extent where one of the more reliable news sources on the country is the corrections section of the New York Times. But the revolutionary process in Venezuela continues to make major strides. While detractors point to long lines for food, people in Venezuela are also pointing to the first anti-GMO seed law in the world, and an ecosocialist Plan of Sowing. While some claim human rights abuses, the National Human Rights Plan launched by the government for 2015-2019 is one of the most comprehensive in the world, also having been written with participation of thousands of people across the country.

For small farmers in Venezuela at the cutting edge of history, the future is now. What is called for both by the grassroots and also by the government, is nothing less than a new geography – where the cities don’t exploit the countryside – and a new calendar – where the seasonal and lunar cycles matter more than the electoral and business cycles.

Monte Carmelo doesn’t rest on its laurels. On October 31st, over fifty people from eight different countries gathered to discuss and debate “the convocation of the First Ecosocialist International.” They invite the world to join them in a return to the source, which takes us beyond the source, like the seed, which unites the soil to the sky.