The possibility of splintering China apart into separate regions, outside of Beijing’s influence, has been an integral part of American foreign policy ever since the end of the 1940s, when China exited Washington’s control following the communist revolution.

The 1949 communist takeover of China was termed in imperialist language as the “loss of China” in Washington. China’s revolution was lamented by American politicians as a major blow to United States power, which it undoubtedly was, after China had been a Western client nation for many years.

The Harry Truman administration (1945–53), severely criticised for “losing China”, made concerted efforts to undermine America’s new rival. Between 1949 and 1951, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) increased the number of its operatives tenfold which were engaged in covert actions relating to China. (1)

The CIA budget, for activities against China, reached 20 times greater than the sum of money expended on the 1953 US/British-backed overthrow of Mohammad Mosaddegh’s government in Iran. (2)

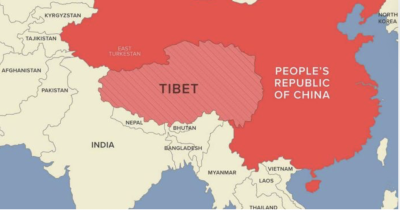

Scanning maps of east Asia, US government strategists were inevitably drawn towards Tibet, in south-western China, as an area of critical importance. The Tibetan landmass, which is recognised internationally to be within China’s frontiers, is the highest in the world, and it has an average altitude of over 4,300 metres above sea level. At 1.2 million square kilometres in size, the region of Tibet is more than twice larger than France; but it doubles to 2.5 million square kilometres, by taking into account much of the surrounding Tibetan Plateau which is scarcely inhabited by humans.

It should be noted, in modern history, that Tibet was under effective Chinese control for almost two centuries (from 1720–1912), during the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China.

After the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso, announced de facto Tibetan independence in early 1913. The Dalai Lama insisted that he was assuming spiritual and political leadership of Tibet, outside of China’s auspices. In the autumn of 1950, now a year in power, the Chinese leader Mao Zedong and his entourage – viewing Tibet as consisting of China’s historical territory – dispatched an army of 40,000 men to subdue the Tibetan independent forces, and to reintegrate Tibet to China’s authority.

Beijing went a long way to achieving its ambition in Tibet through military force, during the Battle of Chamdo (6–24 October 1950), which took place in eastern Tibet and resulted in a decisive Chinese victory. The Tibetan fighters were greatly outnumbered, and around 3,000 of them ended up surrendering to the Chinese troops.

The 14th (and current) Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, stressed that the Chinese soldiers did not attack Tibetan civilians in Chamdo, and he said they “were very disciplined” and “distributed some money” to the locals (3). Tibet was officially reincorporated or annexed to China just 7 months later, in May 1951.

The 14th (and current) Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, stressed that the Chinese soldiers did not attack Tibetan civilians in Chamdo, and he said they “were very disciplined” and “distributed some money” to the locals (3). Tibet was officially reincorporated or annexed to China just 7 months later, in May 1951.

Beijing’s military offensive in Tibet was immediately condemned by China’s neighbour, India, as being “deplorable” and “not in the interest of China or peace” (4). This position was strongly supported by India’s allies, America and England. Not mentioned was that the Western-backed Chinese politician, the anti-communist Chiang Kai-shek, had previously stated his desire for the restoration of Tibet to China’s control.

On 20 December 1941, Chiang Kai-shek wrote in his diary that Tibet should be claimed by China once the Second World War is over, along with other regions like Xinjiang and Outer Mongolia. In 1942, Chiang Kai-shek then drew up plans for the return of Taiwan and Manchuria to China. (5)

From late 1950 the US Congress, meanwhile, considered Tibet to be a region occupied by China and which was entitled to self-determination. Tom Lantos, an American politician with the Democratic Party noted, “Only when Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party came to power, and Washington broke diplomatic relations with Beijing, did sympathy for the Tibetans begin showing up at the State Department”. (6)

It was around this time, from the beginning of the 1950s, that the Dalai Lama started to receive funding from the CIA; although the Dalai Lama may actually have been obtaining CIA money from the late 1940s, and he later maintained contact with CIA agents operating freely in Tibet. (7)

From 1956, when anti-Beijing revolts broke out in the eastern Tibetan regions of Amdo and Kham, the CIA became actively involved in assisting the rebellions (8). From 1956 to 1957, the CIA trained between 250 to 300 “Tibetan freedom fighters” within the United States itself, at Camp Hale in the state of Colorado, astride the southern part of the Rocky Mountains. At Camp Hale, which was constructed for the US military in 1942, the Tibetan rebels were trained and organized under the supervision of Bruce Walker, a CIA officer.

Following completion of training at Camp Hale, the Tibetan insurgents were transported by CIA and US Air Force planes to a secret base for operations against China, located in Aspen, the Colorado mountain resort. Once the aircraft were positioned over the facility at Aspen, the Tibetans would jump out and deploy their parachutes.

The CIA was also training Tibetan fighters in the region of Tibet. The scholar Melvyn Goldstein, an expert on Tibet wrote, “The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) immediately made contact with the [Tibetan] resistance leaders, and by 1957 had begun to train and provide weapons to Tibetan guerrilla forces” (9). In May 1957, a rebel group in Tibet with its own fighting unit was created with the help of the CIA.

The Americans had already placed on their payroll the Dalai Lama’s older brother, Gyalo Thondup, who like his sibling is still alive today. In 1951 Thondup travelled to Washington, and he became a key source of information for the US State Department regarding the situation in Tibet. For example, the CIA learned from Thondup in 1952 that there were between 10,000 to 15,000 Chinese troops stationed in Tibet.

The CIA offered assurances to Thondup that it would assist in securing Tibet’s independence from China. In return, Thondup agreed to aid the Americans in preparing guerrilla forces in Tibet to fight against Mao Zedong’s soldiers.

A CIA intelligence report, from September 1952, acknowledged there would be serious difficulties in successfully aiding the Tibetan resistance against the might of the Chinese Army (People’s Liberation Army). The CIA developed and organised Operation ST-Circus in 1959, a covert war against Chinese influence in Tibet using guerrilla warfare, and which was headed by the Dalai Lama’s brother (10). ST-Circus turned into a fiasco as the insurgency was overcome easily by Beijing’s troops, resulting in thousands of deaths.

Through this secret war in Tibet, the CIA was assisted by the intelligence services of India and Nepal. The latter country was also a US ally and shares a lengthy frontier with Tibet. CIA training camps were set up in India and Nepal. There was a joint CIA-Indian command centre in the capital city of India, New Delhi.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, hundreds of Tibetans were flown to the American-controlled islands of Guam and Okinawa, where they underwent development as guerrilla fighters (11). The Tibetan insurgents were subsequently flown back to Tibet where they exited the airplanes by parachute. The CIA provided air drops to the rebels which contained mortars, grenades, rifles and machine guns.

The March 1959 Tibetan uprising, that erupted in Tibet’s capital city Lhasa, was supported by the US and India. It was an escalation of the Kham and Amdo revolts, which had been encouraged by the Dwight Eisenhower administration (1953-61).

Lasting for 2 weeks, the 1959 uprising was another bloody, expensive and enduring failure: Beijing’s forces smashed it with an iron fist, compelling the Dalai Lama in the second half of March 1959 to flee Lhasa to northern India, along with tens of thousands of his followers. The Americans gave cautious backing to the new Tibetan Government in exile, the Central Tibetan Administration, which was founded in April 1959.

Over elapsing time, the Dalai Lama continued to be subsidised with CIA money. In one year alone, 1964, he received $180,000 in CIA funds (12). The sum of $180,000 in 1964 is presently worth about $1.7 million. The same year, 1964, the CIA provided $500,000 ($4.7 million today) to the training of Tibetan guerrillas in Nepal, while $400,000 ($3.8 million today) was spent on training other Tibetans at Camp Hale in Colorado in 1964. The CIA forked out that year $185,000 for the transportation of the Tibetans at Camp Hale, who were flown to India. (13)

Documents released by the US State Department in August 1998 stated that, from the late 1950s until the mid-1970s, the Dalai Lama in fact received $180,000 every year for his assistance during that period (14). The Dalai Lama’s retinue denied that the spiritual leader ever pocketed any of the cash himself. The Dalai Lama, who is no fool and can speak several languages including Chinese and English, later admitted, “the C.I.A.’s motivation for helping was entirely political”.

From the summer of 1959 a Tibetan guerrilla unit, known as the Chushi Gangdruk Volunteer Defense Force, was receiving weapons and training from the CIA. This group was operating from the Himalayan mountains of Nepal, from which its forces would advance and ambush unsuspecting Chinese troops, or commit sabotage against their supply lines. At different times, the rebels were assisted by CIA-contract mercenaries and CIA planes roaming overhead. (15)

By the mid-1960s, the Chushi Gangdruk force had nearly 2,000 fighters of Khampa ethnicity, from the Kham area of eastern Tibet, and which were now being commanded by CIA officers. One of the Tibetan fighters Nawang Gayltsen recalled, “None of us knew how to fight the Chinese the modern way. But the Americans taught us. We learned camouflage, spy photography, guns and radio operation. We played ping-pong on Sundays”. (16)

In the games room at Camp Hale there was a portrait of Eisenhower, which was signed by the US president at the bottom, “To my fellow Tibetan friends, from Eisenhower” (17). Nawang said he had been taught how to destroy bridges by his CIA instructors at Camp Hale. The insurgents were paid directly by the Americans to attack Chinese government facilities, infrastructure and machinery in Tibet. If the raids were successful, the CIA would increase the payment to the rebels.

According to author Joe Bageant, the final CIA arms drop to the Tibetan forces occurred in May 1965 (18). By then, American government attention under president Lyndon Johnson (1963–69) was shifting increasingly to the US war in Vietnam, which the Johnson White House escalated sharply in the mid-1960s.

Roger McCarthy, a CIA officer formerly in charge of the Tibetan program said, “Generally speaking, I think the Agency [CIA] looks at Tibet as having been one of the best operations that it has ever run… But if you look at the final results, it’s a very sad commentary. If we look at what we did to Tibet as about the best that we could do, then I say that we failed miserably”.

The CIA continued its operations against the Chinese alongside the Tibetan guerrillas until 1974, as relations between the US and China began to thaw at that time, on the surface at least. It was also in 1974 that the CIA funding to the Dalai Lama suddenly ceased. (19)

***

Notes

1 Luiz Alberto Moniz Bandeira, The Second Cold War: Geopolitics and the Strategic Dimensions of the USA (Springer 1st edition, 23 June 2017) p. 76

2 Ibid.

3 Thomas Laird, The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama (Grove Press; 1st Trade Paper edition, 10 October 2007) p. 305

4 Madhur Sharma, “Explained: The China-Tibet 17-Point Agreement, The Conflict’s History, And India’s Place In It”, OutlookIndia, Updated 23 May 2022

5 Rana Mitter, China’s Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism (Belknap Press, 27 January 2023) p. 45

7 Bandeira, The Second Cold War, p. 77

9 Melvyn Goldstein, “The United States, Tibet, and the Cold War”, Journal of Cold War Studies, Summer 2006, Jstor, p. 4 of 20

10 Bandeira, The Second Cold War, p. 75

11 Paul Salopek, “The CIA’s Secret War in Tibet”, Chicago Tribune, 26 January 1997

12 Bandeira, The Second Cold War, p. 76

13 Ibid.

14 Dennis G. Fitzgerald, Informants, Cooperating Witnesses, and Undercover Investigations, A Practical Guide to Law, Policy, and Procedure (CRC Press Incorporate, 2nd edition, 5 November 2014) p. 15

15 Bennett, “Tibet, the ‘great game’ and the CIA”, Global Research

16 Salopek, Chicago Tribune

17 Joe Bageant, “CIA’s Secret War in Tibet”, HistoryNet, 12 June 2006

18 Ibid.

19 Fitzgerald, Informants, Cooperating Witnesses, and Undercover Investigations, p. 15

The 14th (and current) Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, stressed that the Chinese soldiers did not attack Tibetan civilians in Chamdo, and he said they “were very disciplined” and “distributed some money” to the locals (3). Tibet was officially reincorporated or annexed to China just 7 months later, in May 1951.

The 14th (and current) Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, stressed that the Chinese soldiers did not attack Tibetan civilians in Chamdo, and he said they “were very disciplined” and “distributed some money” to the locals (3). Tibet was officially reincorporated or annexed to China just 7 months later, in May 1951.