About Poland and Ukraine Being One Country for 400 Years Is Misleading. Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski’s Quip

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Global Research Fundraising: Stop the Pentagon’s Ides of March

***

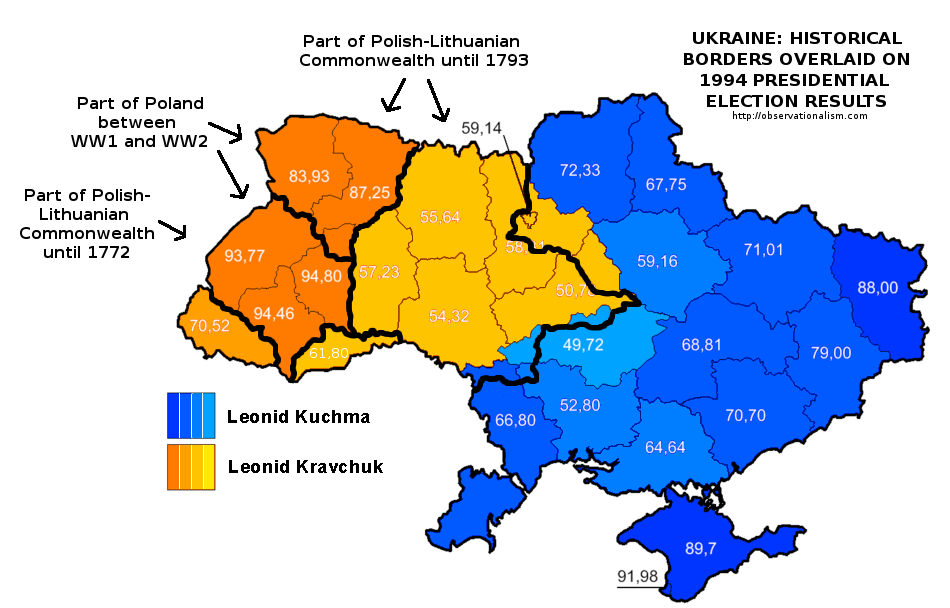

All these lands constituted the territory of the loose Polish-Lithuanian Union after Krewo in 1385 and the tighter Commonwealth after Lublin in 1569, but Warsaw only had direct rule over Eastern Ukraine for less than a century, parts of Western Ukraine for 230-360 years, and Eastern Galicia for over 420 years.

Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski recently told German press agency dpa that “Ukraine and Poland have been one country for 400 years. [Conventionally interveningin Ukraine] would provide fodder for Russian propaganda. Therefore, we should be the last ones to do so.” His quip about those two’s history is misleading, however, since both the length of time that they were together as well as the nature of their relations are disputable.

Regarding the first, the Union of Krewo in 1385 led to the creation of the loose Polish-Lithuanian Union, which was the precursor of the tighter Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that emerged from the 1569 Union of Lublin. For the nearly two centuries between those two unions, the vast majority of modern-day Ukraine was under the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s control with the exception of Eastern Galicia and Western Podolia, within which are the well-known city of Lwow and town of Kamieniec Podolski.

The Crown Kingdom of Poland only took control of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s modern-day Ukrainian regions after the Commonwealth’s creation, thus meaning that the majority of what’s nowadays known as Ukraine was part of Poland itself for less than 230 years, not 400. Less than a century later, the 1667 Treaty of Andrusovo, which ended the Polish-Russian War that was sparked by the Khmelnitsky Uprising a few years prior, saw St. Petersburg wrest control of Kiev and most of Eastern Ukraine from Warsaw.

Poland then lost Polish-majority Western Galicia (with the exception of Krakow) and Ukrainian-majority Eastern Galicia to Austria a little over 100 years after that during the first partition in 1772.

Western Podolia and most of the Ukraine’s remaining western regions then followed slightly more than two decades later after the second partition of 1793 gave them to Russia. The third partition just two years later in 1795 then saw Russia take the rest of Poland’s majority-Ukrainian-inhabited lands.

Eastern Galicia’s Lwow was part of the Polish Crown since 1349, Western Podolia’s Kamieniec Podolski officially joined in 1430 but switched hands with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania for decades before that since the mid-14th century, while the rest of Ukraine’s western regions came under its control in 1569. Accordingly, the first was part of Poland for over 420 years, the second for at least 360 years though possibly longer depending on how one measures it, and the last for less than 230 years.

It should also be mentioned that the never-implemented Treaty of Hadiach from 1658 would have trifurcated the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by carving out a “Ruthenian” (old-style term for what are nowadays Ukrainians) Duchy from most of Poland’s formerly Lithuanian lands apart from Volhynia. This is relevant in the context of Sikorski’s quip since it shows that some of those Ukrainian elites that remained under Warsaw’s control after the Khmelnitsky Uprising wanted a separate political identity.

The purpose in sharing these facts is to show that Polish-Ukrainian history isn’t as simple as he portrayed it as being at the geopolitical level, not to mention the local one as proven by the 1648-1657 Khmelnitsky Uprising and the 1468-1769 “Koliivshchyna”, both of which were anti-Polish bloodbaths. Sikorski wanted to signal support for Ukraine, but in doing so, he might have ruffled some folks’ feathers with his misleading claim that overlooks Lithuania’s historical autonomy from 1385 onwards.

The Grand Duchy was an equal member of the Commonwealth alongside the Polish Crown, not a province or vassal of the latter like casual outside observers oftentimes assume. While each were technically part of the same country, they also de facto functioned as their own states due to the wide autonomy that they preserved to administer their internal affairs, which is why the notion that Lithuanian-controlled modern-day Ukraine was “part” of Poland isn’t what most folks might imagine.

All these lands constituted the territory of the loose Polish-Lithuanian Union after Krewo in 1385 and the tighter Commonwealth after Lublin in 1569, but Warsaw only had direct rule over Eastern Ukraine for less than a century, parts of Western Ukraine for 230-360 years, and Eastern Galicia for over 420 years. Throughout that entire time, a separate Ukrainian identity was forming, and its roots laid the basis for the fascist interpretation thereof that arose during the interwar years and was revived after 2014.

Oversimplifying the geopolitical dimension of Polish-Ukrainian history like Sikorski did by claiming that they’ve “been one country for 400 years” overlooks the key facts touched upon in this piece that account for the present state of socio-political affairs in this former Soviet Republic. It misleads casual outside observers into thinking that bilateral ties are much better than they presently are due to their shared history, which is actually more complicated than he let on and seen very differently by both.

It’s important to dispel the illusion that Sikorski reinforced since it distracts from Ukraine’s three-month-long anti-Polish infowar campaign that was detailed here in mid-March. To be sure, there’s no longer any crisis in bilateral ties like they briefly experienced late last year under Poland’s former conservative-nationalist government, but trouble is still brewing. Upon becoming aware that their history isn’t as simple as he made it seem, casual outside observers can better these dynamics as they unfold.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

This article was originally published on Andrew Korybko’s Newsletter.