History: Rivalry Between France and Germany

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

In the immediate years after World War I, France seemed to have gained an impregnable position in mainland Europe. France’s old rival, Germany, was weakened and humiliated following the retreat of its armed forces across the frontlines in the autumn of 1918 against the French, British and American armies.

During the 1920s the French would secure alliances with states such as Czechoslovakia, Romania and Poland, along with some of the emerging Balkan nations. France at this time also possessed one of the biggest armies in the world, whereas the German Army had been greatly reduced in size. These apparent shows of strength concealed real frailties, however.

The weaker European countries that aligned themselves to France proved to be liabilities rather than assets. After 1918 the French willingly severed ties with its former ally, Russia, in part because of ideological biases towards the Bolshevik government.

Poland was continually encouraging the rise in anti-Russian feelings within France. The Poles, sometimes in the most opportunistic manner, were keen to take advantage of political or military situations which might prove detrimental to the Russian state.

Successive French governments were hostile towards Soviet Russia, which had met firm favour in Warsaw. These self-defeating actions would cost both France and Poland dear when a second global war loomed in the late 1930s. Paris had claimed that the Soviets refused to honour the debts that Tsar Nicholas II previously contracted with France.

Relations between France and Britain also deteriorated after the fighting ended in November 1918. There were disagreements in Paris and London over issues such as war debt payments, reparations and disarmament.

A feeling persisted in England, which was hardly ever publicly expressed, that they had been tricked into fighting a continental war for French interests, by helping the latter to reclaim its supremacy over Germany and the region of Alsace-Lorraine. The British gained nothing from the First World War except a huge casualty list among its soldiers and the further decline of its hegemony.

France may not have been defeated in World War I, but they were assisted a great deal in this by Britain, Russia and during the final year of the conflict, America. With the war over, at the root of French weakness was the loss of her wartime allies, particularly Russia with its vast pool of manpower and resources. The Russians have possessed enough strength to take care of themselves but France was weaker and especially needed alliances with powerful states.

On their own the French had not won a major conflict in Europe since the early 19th century under Napoleon. One of Britain’s leading commanders of the First World War, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, wrote in late May 1917 “our French allies had already shown that they lacked both the moral qualities and the means of gaining victory”.

French poilus (soldiers) posing in a trench, 16 June 1917. Note the Adrian helmets. (Licensed under the Public Domain)

There was truth to Haig’s criticisms and, to his dismay, in the spring and summer of 1917 the French Army was in the process of disintegration having been unable to cope with the rigours of a large-scale war. After weeks of upheaval by 9 June 1917 insurrections and rebellions had spread to 54 divisions throughout the French Army, amounting to hundreds of thousands of men.

In addition even in those units where no insurrection took place, more than half of French soldiers returning from leave were arriving back in a state of drunkenness. The French military command, under pressure, later acknowledged that 170 acts of rebellion had occurred across the army’s ranks between April to June 1917, though the real number was probably higher than that.

A total collapse of the French Army did not unfold but it came close to happening; as punishment for the ringleaders of the many rebellions, the military leadership resorted to extreme measures like executions by firing squad and extensive periods of penal servitude.

Increasing numbers of British and American troops were reinforcing the Allied frontlines through 1917, which was vital in restoring some of the French morale, temporarily at least. The widespread unrest in the French Army was thereafter not adequately addressed or cured. France had suffered a very high loss of life during the war. Almost half of the soldiers available to the French Army in 1914 would either be killed or wounded over the next four years.

The casualty rate led to permanent psychological damage within the army. Numerous French troops came to believe the price of victory was no longer worth paying. This feeling was passed on unchanged to the next generation of French soldiers. Most of the fighting on the Western front during World War I had taken place in France, not Germany. Subsequently, French military thinking became wholly negative and based on outmoded First World War doctrines.

Poor discipline and fighting spirit among French troops indeed persisted in the interwar years. The complete capitulation came in 1940 when the French Army was faced with a strong and motivated Wehrmacht.

The warning signs had been on display for British officers to see like Lieutenant-General Alan Brooke, who would become the head of the British Army in December 1941. A few weeks after the fall of Poland in September 1939, General Brooke attended a ceremonial parade of the French 9th Army, commanded by General André Corap.

General Brooke was disturbed to see that many of the French soldiers had “insubordinate” and sulky expressions on their faces. He noticed too their uniforms and equipment were often untidy and not properly cared for, and they did not march in unison but slouched past out of line. A few months later Brooke was not terribly surprised to learn that the French 9th Army fell to pieces, following Nazi Germany’s western invasion in May 1940.

A generation prior to that, a partial collapse in the morale of the Austro-Hungarian Army had taken place in the summer of 1916, two years into the First World War, when they were faced with a major Russian offensive overseen by General Aleksei Brusilov. Austro-Hungarian divisions, in particular Bohemian troops, deserted from the battlefield in considerable numbers, unable to cope with determined and well-trained Russian soldiers. After two years of fighting against the Russian Army, the Austro-Hungarian forces were depleted and in disarray.

Growing discontent was on display, for example, in the Wehrmacht when its invasion of Russia was faltering in the autumn of 1941. Tensions and open acrimony developed between the German army high command, field commanders, and ordinary frontline troops, though nothing like on the scale of the French in 1917.

That Germany by this point had already gained its revenge over the Franco-British forces in the summer of 1940 was not altogether unexpected. At the end of World War I the Germans were treated shabbily enough by the Allied powers, but the potential remained within Germany for the country to recover its influence and become one of Europe’s strongest nations again.

Italian philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli said centuries before that an enemy should either be killed or ruined beyond any possibility of recovery, or he should be treated leniently, depending on the circumstances. With the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, the Western Allies neither dismantled Germany nor treated the country generously. The Germans were instead wounded and a wounded animal is a dangerous one. Before long he will recover from his wounds and seek retaliation.

French political and military leaders like Georges Clemenceau and Ferdinand Foch, both staunch anti-Germans, knew this very well. Clemenceau wanted to forever remove the German threat to France by dismembering Germany. In not doing so he feared that in a future conflict the odds would be heavily in Germany’s favour, and that France might not have the same allies to call upon in the next war.

Clemenceau knew as well the German population remained quite larger than that of France. In 1920 there were 62 million Germans and just 39 million French people. German industrial potential continued to be greater than France too. When the French war hero Marshal Foch saw the terms laid down by the Versailles Treaty he had said, “This is not peace. It’s an armistice for 20 years”. As with Clemenceau, Foch desired the breaking up of Germany into different states.

It could be argued as a result that the First World War’s outcome was inconclusive, a view which Clemenceau and Foch may well have agreed with. The territories of the nations that failed to secure victory were not occupied for long periods by foreign armies. The Second World War had been a direct consequence of the First World War, with an uneasy 20-year armistice in between as Marshal Foch predicted.

In the two world wars Russia, Britain, France and America had fought against Germany and various allies of the Germans. A clear result was reached in 1945 with the Axis powers’ unconditional surrender. Yet World War II, unlike its predecessor, was a necessary war in that the fascist states, above all Nazi Germany, had to be soundly defeated and demilitarised.

At the conclusion of World War I the British had wanted Germany to survive as a nation, in the main because they believed that Germany’s continued existence would help to prevent the spread of communism. Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for War and Air, did not want the disbanding of the German Army in 1919, as he felt it might be needed to assist in thwarting the perceived threat posed by Soviet Russia.

Churchill disagreed with the harsh terms of the Versailles Treaty aimed at Germany, and he feared it would lead to another continental war. Churchill wanted Britain to be as he said “the ally of France and the friend of Germany”.

In comparison Churchill’s attitude towards the Bolshevik government in Russia was belligerent and unhelpful, at least in part because of his entrenched anti-communism. Churchill supported the unprovoked Allied invasion of Russia in 1918 and British military involvement in the conflict against the Red Army.

Churchill had not relished the prospect of France gaining an unassailable position in mainland Europe after 1918, which was part of the reason he wanted the Germans to be treated leniently. Most British politicians hoped that Germany would gradually recover but not to again threaten British interests. London simply wanted a counterbalance to the French in central Europe.

Economic policies in Europe during the 1920s came as a reaction to World War I, along with growing domestic unrest. In Britain in 1926 a general strike, the biggest in the country’s history, was eventually broken by the Conservative government as a restless industrial peace then settled over the United Kingdom.

Communist propaganda was blamed for the revolts in Britain’s overseas possessions such as India, but the instability brought on by World War I was actually the cause of the uprisings. Between 1914 and 1918, the inhabitants of Britain’s colonial empire realised for the first time that Britain was not the world’s dominant state after all, but was in fact one of several great powers.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

This article was originally published on Geopolitica.RU.

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree and he writes primarily on foreign affairs and historical subjects. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Sources

“1917, Georges Clemenceau named French prime minister”, History.com, 16 November 2009

Timothy C. Dowling, The Brusilov Offensive (Indiana University Press, 18 June 2008)

J. P. Harris, “Douglas Haig”, Oxford Bibliographies, 29 November 2022

Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill: World in Torment, 1916-1922 (Hillsdale College Press, 1 January 2008)

Evan Mawdsley, Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War, 1941-1945 (Hodder Arnold, 23 February 2007)

Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars (Random House Value Publishing, 2nd edition, 3 April 1985)

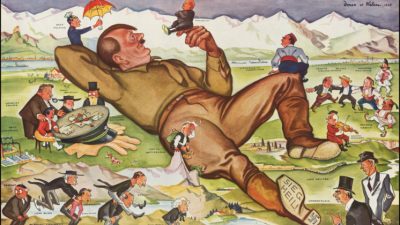

Featured image is from Geopolitica.RU