Eighty Years Ago… The Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 23, 1939: Myth and Reality

In a remarkable book, 1939: The Alliance That Never Was and the Coming of World War II, the Canadian historian Michael Jabara Carley describes how, at the end of the 1930s, the Soviet Union repeatedly tried, but finally failed, to conclude a pact of mutual security, in other words a defensive alliance, with Britain and France. This proposed arrangement was intended to counter Nazi Germany, which, under Hitler’s dictatorial leadership, had been behaving more and more aggressively, and it was likely to involve some other countries, including Poland and Czechoslovakia, that had reason to fear German ambitions. The protagonist of this Soviet approach to the Western powers was the minister of foreign affairs, Maxim Litvinov.

Moscow was eager to conclude such a treaty because the Soviet leaders knew only too well that, sooner or later, Hitler intended to attack and destroy their state. Indeed, in Mein Kampf, published in the 1920s, he had made it very clear that he despised it as “Russia ruled by the Jews” (Russland unter Judenherrschaft), because it was the fruit of the Russian Revolution, the handiwork of Bolsheviks, who were supposedly nothing but a bunch of Jews. And in the 1930s, virtually everybody with some interest in foreign affairs knew only too well that, with his remilitarization of Germany, his large-scale rearmament program, and other violations of the Versailles Treaty, Hitler was preparing for a war of which the victim was to be the Soviet Union. This was demonstrated quite clearly in a detailed study written by a leading military historian and political scientist, Rolf-Dieter Müller, entitled Der Feind steht im Osten: Hitlers geheime Pläne für einen Krieg gegen die Sowjetunion im Jahr 1939 (“The enemy is in the east: Hitler’s secret plans for war against the Soviet Union in 1939.”)

Hitler, then, was building up Germany’s military and intended to use it to wipe the Soviet Union off the face of the earth. From the viewpoint of the elites that were still very much in power in London, Paris, and elsewhere in the so-called Western world, this was a plan they could only approve of and wished to encourage and even support. Why? The Soviet Union was the incarnation of the dreaded social revolution, the source of inspiration and guidance for revolutionaries in their own countries and even in their colonies, because the Soviets were also anti-imperialists who, via the Komintern (or Third International), supported the struggle for independence in the colonies of the western powers.

Via an armed intervention in Russia in 1918-1919, they had already tried to slay the dragon of the revolution that had raised its head there in 1917, but that project had failed miserably. The reasons for this fiasco were: on the one hand, the tough resistance put up by Russian revolutionaries, who enjoyed the support of the majority of the Russian people and of many other peoples of the former czarist empire; and, on the other hand, opposition within the interventionist countries themselves, where soldiers and civilians sympathized with the Bolshevik revolutionaries and made this known via demonstrations, strikes, and even mutinies The troops had to be withdrawn ingloriously. The gentlemen in power in London and Paris had to settle for creating and supporting anti-Soviet and anti-Russian states – primarily Poland and the Baltic countries – along the western border of the former czarist empire, thus erecting a “cordon sanitaire” that was supposed to shield the West against infection by the Bolshevik revolutionary virus.

In London, Paris, and other capitals of Western Europe, the elites hoped that the revolutionary experiment in the Soviet Union would collapse by itself, but that scenario failed to unfold. To the contrary, starting in the early thirties, when the Great Depression ravaged the capitalist world, the Soviet Union experienced a kind of industrial revolution that allowed the population of enjoy considerable social progress, and the country also became stronger, not only economically but also militarily. As a result of this, the socialist “counter system” to capitalism – and its communist ideology – became more and more attractive in the eyes of plebeians in the West, who increasingly suffered from unemployment and misery. In this context, the Soviet Union became even more of a thorn in the side of the elites in London and Paris. Conversely, Hitler, with his plans for an anti-Soviet crusade, loomed increasingly useful and sympathetic. In addition, corporations and banks, especially American, but also British and French ones, made a lot of money by helping Nazi Germany to rearm and by loaning it much of the money needed to do so. Last, but not least, it was believed that encouraging a German crusade in the East would reduce if not totally eliminate the risk of German aggression against the West. Thus, we can understand why Moscow’s proposals for a defensive alliance against Nazi Germany did not appeal to these gentlemen. But there was a reason why they could not afford to reject these proposals without further ado.

After the Great War, the elites on both sides of the English Channel had been forced to introduce fairly far-reaching democratic reforms, for example a considerable extension of the franchise in Britain. Because of this, it became necessary to take into account the opinion of Labourites as well as other left-wing pests populating the legislatures, and sometimes even to include them in coalition governments. Public opinion, and a considerable part of the media, was overwhelmingly hostile to Hitler and therefore strongly in favour of the Soviet proposal for a defensive alliance against Nazi Germany. The elites wanted to avoid such an alliance, but they also wished to create the impression that they wanted one; conversely, the elites wanted to encourage Hitler to attack the Soviet Union, and even help him to do so, but they needed to ensure that the public never became aware of that. This dilemma yielded a political trajectory whose manifest function was to convince the public that the leaders welcomed the Soviet proposal for a common anti-Nazi front, but whose latent – in other words, real – function was to support Hitler’s anti-Soviet designs: the infamous “appeasement policy,” associated above all with the name of the British prime minister Neville Chamberlain, and his French counterpart, Édouard Daladier.

The partisans of appeasement went to work as soon as Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933 and started to prepare for war, a war against the Soviet Union. Already in 1935, London gave Hitler a kind of green light to rearm by signing a naval treaty with him. Hitler then proceeded to violate all sorts of provisions of the Versailles Treaty, for example by reintroducing compulsory military service in Germany, by arming Germany’s military to the teeth, and, in 1937, by annexing Austria. On each occasion, the statesmen in London and Paris moaned and protested in order to make a good impression on the public but finished by accepting the fait accompli. The public was led to believe that such indulgence was required to avoid war. This excuse was effective at first, because the majority of Brits and Frenchmen did not wish to become involved in a new edition of the murderous Great War of 1914-1918. On the other hand, it soon became obvious that appeasement made Nazi Germany stronger militarily and made Hitler increasingly ambitious and demanding. Consequently, the public eventually felt that enough concessions had been made to the German dictator, and at that point the Soviets, in the person of Litvinov, came forward with a proposal for anti-Hitler alliance. This caused headaches for the architects of appeasement, from whom Hitler expected even more concessions.

Thanks to the concessions that had already been made, Nazi Germany was becoming a military Behemoth, and in 1939 only a common front of the Western powers and the Soviets seemed to be able to contain it, because in case of war, Germany would have to fight on two fronts. Under heavy pressure from public opinion, the leaders in London and Paris agreed to negotiate with Moscow, but there was a fly in the ointment: Germany did not share a border with the Soviet Union, because Poland was sandwiched between those two countries. Officially, at least, Poland was an ally of France, so it could be expected to join a defensive alliance against Nazi Germany, but, the government in Warsaw was hostile towards the Soviet Union, a neighbour that was considered as much a menace as Nazi Germany. It stubbornly refused to allow the Red Army, in case of war, to cross into Polish territory in order to do battle against the Germans. London and Paris declined to put pressure on Warsaw, and so the negotiations did not produce an agreement.

The new border between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia from September 1939 to June 1941, somewhere in the occupied territory of Poland (Public Domain)

In the meantime, Hitler made new demands, this time with respect to Czechoslovakia. When Prague refused to cede territory inhabited by a German-speaking minority known as the Sudeten, the situation threatened to lead to war. This was in fact a unique opportunity to conclude an anti-Hitler alliance with the Soviet Union and militarily strong Czechoslovakia, as partners of the Brits and the French: Hitler would have faced a choice between a humiliating disengagement and virtually certain defeat in a war on two fronts. But that also meant that Hitler would never be able to launch the anti-Soviet crusade the elite in London and Paris were craving. That is why Chamberlain et Daladier did not take advantage of the Czechoslovak crisis to form a common anti-Hitler front with the Soviets, but instead rushed by plane to Munich to conclude with the German dictator a deal in which the Sudeten lands, which happened to include the Czechoslovak version of the Maginot Line, were offered to Hitler on a silver platter. The Czechoslovak government, which had not even been consulted, had no choice but to submit, and the Soviets, who had offered military assistance to Prague, were not invited to this infamous meeting.

In the “pact” they concluded with Hitler in Munich, the British and French statesmen made enormous concessions to the German dictator; not for the sake of keeping peace, but so they could continue to dream of a Nazi crusade against the Soviet Union. But to the people of their own countries, the agreement was presented as a most sensible solution to a crisis that threatened to trigger a general war. “Peace in our time!” is what Chamberlain proclaimed triumphantly upon his return to England. He meant peace for his own country and its allies, but not for the Soviet Union, whose destruction at the hands of the Nazis he eagerly awaited.

In Britain there were also politicians, including a handful of bona fide members of the country’s elite, who opposed Chamberlain’s appeasement policy, for example Winston Churchill. They did not do so out of sympathy for the Soviet Union, but they did not trust Hitler and feared that appeasement might be counter-productive in two ways. First, the conquest of the Soviet Union would provide Nazi Germany with virtually unlimited raw materials, including petroleum, fertile land, and other riches, and thus allow the Reich to establish on the European continent a hegemony that would represent a greater danger for Great Britain than Napoleon had ever been. Second, it as also possible that the power of Nazi Germany and the weakness of the Soviet Union were both overestimated, so that Hitler’s anti-Soviet crusade might actually produce a Soviet victory, with as a result a potential “bolshevization” of Germany and perhaps all of Europe. This is why Churchill was extremely critical of the agreement concluded at Munich. He allegedly remarked that, in the Bavarian capital, Chamberlain had been able to choose between dishonour and war, that he had chosen dishonour, but that he would also get war. With his “peace in our time,” Chamberlain did in fact err lamentably. Merely one year later, in 1939, his country would become embroiled in a war against Nazi Germany which, thanks to the scandalous pact of Munich, had become an even more formidable foe.

The major determinant of the failure of the negotiations between the Anglo-French duo and the Soviets had been the appeasers’ unspoken unwillingness to conclude an anti-Hitler agreement. An auxiliary factor was the refusal of the government in Warsaw to allow the presence of Soviet troops on Polish territory in case of war against Germany. That provided Chamberlain and Daladier with a pretext for not concluding an agreement with the Soviets, a pretext needed to satisfy public opinion. (But other excuses were also conjured up, for example the alleged weakness of the Red Army, which supposedly made the Soviet Union a useless ally.) With respect to the role played by the Polish government in this drama, there exist some serious misunderstandings. Let us take a closer look at them.

First of all, it should be taken into account that interwar Poland was not a democratic country, far from it. After its (re)birth at the end of the First World War as a titular democracy, it did not take very long before the country found itself ruled with an iron hand by a military dictator, general Józef Pilsudski, on behalf of a hybrid elite representing the aristocracy, the Catholic Church, and the bourgeoise. This un- and anti-democratic regime continued to govern after the general’s death in 1935, under the leadership of “Pilsudski’s colonels,” whose primus inter pareswas Józef Beck, the minister of foreign affairs. His foreign policy did not reflect warm feelings towards Germany, which had lost a part of its territory to the advantage of the new Polish state, including a “corridor” that separated the German region of East Prussia from the rest of the Reich; and there was also friction with Berlin on account of the important Baltic seaport of Gdansk (Danzig), declared to be an independent city-state by the Versailles Treaty, but claimed by both Poland and Germany.

Poland’s attitude towards its eastern neighbour, the Soviet Union, was even more hostile. Pilsudski and other Polish nationalists dreamed of a comeback of the great Polish-Lithuanian empire of the 17thand 18thcenturies that had stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea. And he had taken advantage of the revolution and subsequent civil war in Russia to grab a vast piece of territory of the former czarist empire during the Russian-Polish War of 1919-1921. This territory, to become known rather inaccurately as “Eastern Poland,” extended for several hundred kilometers to the east of the famous Curzon Line that ought to have been the eastern border of the new Polish state, at least according to the Western powers that had been the godfathers of the new Poland at the end of the Great War. The region was essentially populated by White Russians and Ukrainians, but in the following years Warsaw was to “polonize” it as much as possible by bringing in Polish settlers. The flames of Polish hostility towards the Soviet Union were also fanned by the fact that the Soviets sympathized with the communists and other plebeians who opposed the patrician regime in Poland itself. Finally, the Polish elite was anti-Semitic and had embraced the concept of Judeo-bolshevism, the notion that communism and all other forms of Marxism were part of a nefarious Jewish plot, and that the Soviet Union, the product of a Bolshevik and therefore supposedly Jewish revolutionary scheme, amounted to nothing other than “Russia ruled by the Jews.” Even so, relations with the two powerful neighbours were normalized as much as possible under Pilsudski by the conclusion of two non-aggression treaties, one with the Soviet Union in 1932 and one with Germany soon after Hitler’s advent to power, namely in 1934.

After the death of Pilsudski, the Polish leaders continued to dream of territorial expansion to the borders of the quasi-mythical Great Poland of a distant past. For the realization of this dream, there seemed to exist numerous possibilities in the east, and particularly in the Ukraine, a part of the Soviet Union that stretched invitingly between Poland and the Black Sea. Despite disputes with Germany and a formal alliance with France, which counted on Polish help in case of a conflict with Germany, first Pilsudski himself, and then his successors, flirted with the Nazi regime in the hope of a joint conquest of Soviet territories. Anti-Semitism was another common denominator of two regimes that hatched schemes to rid themselves of their Jewish minorities, for example, via deportation to Africa.

Warsaw’s rapprochement to Berlin reflected the megalomania and naivety of the Polish leaders, who believed that their country was a great power of the same caliber as Germany, one that Berlin would respect and treat as a full-fledged partner. The Nazis kindled this illusion, because by doing so they weakened the alliance between Poland and France. The Polish eastern ambitions were also encouraged by the Vatican, which expected considerable dividends to flow from Catholic Poland’s conquests in mostly Orthodox Ukraine, viewed as ripe for conversion to Catholicism. It is in this context that a new myth was conjured up by the propaganda machine of Goebbels in collaboration with Poland and the Vatican, namely the fiction of a famine orchestrated by Moscow in the Ukraine; the idea was to be able to present future Polish and German armed interventions there as a humanitarian action. This myth was to be resuscitated during the Cold War and become the creation myth of the independent Ukrainian state that emerged from the ruins of the Soviet Union. (For an objective view of this famine, we refer to the many articles of the American historian Mark Tauger, an expert in the history of Soviet agriculture; they have been published together in a French edition, Famine et transformation agricole en URSS.)

Knowledge of this background allows us to understand the attitude of the Polish government at the time of the negotiations for a common defensive front against Nazi Germany. Warsaw obstructed these negotiations, not out of fear of the Soviet Union but, to the contrary, because of anti-Soviet aspirations and its concomitant rapprochement to Nazi Germany. In this respect, the Polish elite found itself on the same wavelength as its British and French counterparts. Thus, we can also understand why, after the conclusion of the Munich agreement, which allowed Nazi Germany to annex the Sudeten region, Poland grabbed a piece of the Czechoslovak territorial loot, namely the town of Teschen and its surroundings. By descending on this part of Czechoslovakia like a hyena, as Churchill remarked, the Polish regime revealed its real intentions – and its complicity with Hitler.

The concessions made by the architects of appeasement made Nazi Germany stronger than ever before and made Hitler more confident, arrogant, and demanding. After Munich, he revealed himself far from satiated, and in March 1939 he violated the Munich Agreement by occupying the rest of Czechoslovakia. In France and Britain, the public was shocked, but the ruling elites did nothing other than to express the hope that “Herr Hitler” would eventually become “sensible,” that is, start his war against the Soviet Union. Hitler had always had the intention to do so but, before indulging the British and French appeasers, he wanted to extort some more concessions from them. After all, there seemed to be nothing they could refuse him; furthermore, having made Germany so much stronger via their earlier concessions, were they in a position to deny him the presumably final little favour he asked for? That final little favour concerned Poland.

Towards the end of March 1939, Hitler suddenly demanded Gdansk as well as some Polish territory between East Prussia and the rest of Germany. In London, Chamberlain and his fellow arch-appeasers were in fact inclined to give in again, but the opposition emanating from the media and the House of Commons proved too strong to allow that to happen. Chamberlain then suddenly changed course, and on March 31 he formally – but totally unrealistically, as Churchill remarked – promised Warsaw armed assistance in case of a German aggression against Poland. In April 1939, when opinion polls revealed what everybody already knew, namely that almost ninety percent of the British population wanted an anti-Hitler alliance on the side of the Soviet Union as well as France, Chamberlain found himself obliged to officially display an interest in the Soviet proposal for talks about “collective security” in the face of the Nazi threat.

In reality, the partisans of appeasement were still not interested in the Soviet proposal, and they thought of all kinds of pretexts to avoid concluding an agreement with a country they despised and against a county they secretly sympathized with. It was only in July 1939 that they declared themselves ready to start military negotiations, and it was only in early August that a Franco-British delegation was sent to Leningrad for that purpose. In stark contrast to the speed with which, one year earlier, Chamberlain himself (accompanied by Daladier) had rushed by plane to Munich, this time a team of anonymous underlings were shipped to the Soviet Union on board a slow freighter. Furthermore, when, having passed through Leningrad, they finally arrived in Moscow on August 11, it turned out that they did not possess the credentials or authority required for such discussions. By this time, the Soviets had had enough, and one can understand why they broke off the negotiations.

In the meantime, Berlin had discreetly launched a rapprochement towards Moscow. Why? Hitler felt betrayed by London and Paris, who had earlier made all sorts of concessions but now denied him the trifle of Gdansk and sided with Poland, and thus faced the prospect of war against Poland, which refused to let him have Gdansk, and against the Franco-British duo. To be able to win this war, the German dictator needed the Soviet Union to remain neutral, and for that he was willing to pay a high price. From Moscow’s perspective, Berlin’s overture contrasted starkly with the attitude of the Western appeasers, who demanded that the Soviets make binding promises of assistance, but without offering a meaningful quid pro quo. What had started between Germany and the Soviet Union in Mayas informal discussions within the context of commercial negotiations without great importance, in which the Soviets initially did not show interest, eventually morphed into a serious dialogue involving the two countries’ ambassadors and even foreign ministers, namely Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov – the latter having replaced Litvinov.

Ribbentrop taking leave of Molotov in Berlin, November 1940 (CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

A factor that played a secondary role but should nonetheless not be under-estimated is the fact that, in the spring of 1939, Japanese troops based in Northern China had invaded Soviet territory in the Far East. In August, they would be defeated and pushed back, but this Japanese threat confronted Moscow with the prospect of having to fight a war on two fronts, unless a way was found to eliminate the threat emanating from Nazi Germany. Moscow was offered a way to neutralize this threat by Berlin’s overtures. reflecting its own desire to avoid a two-front war.

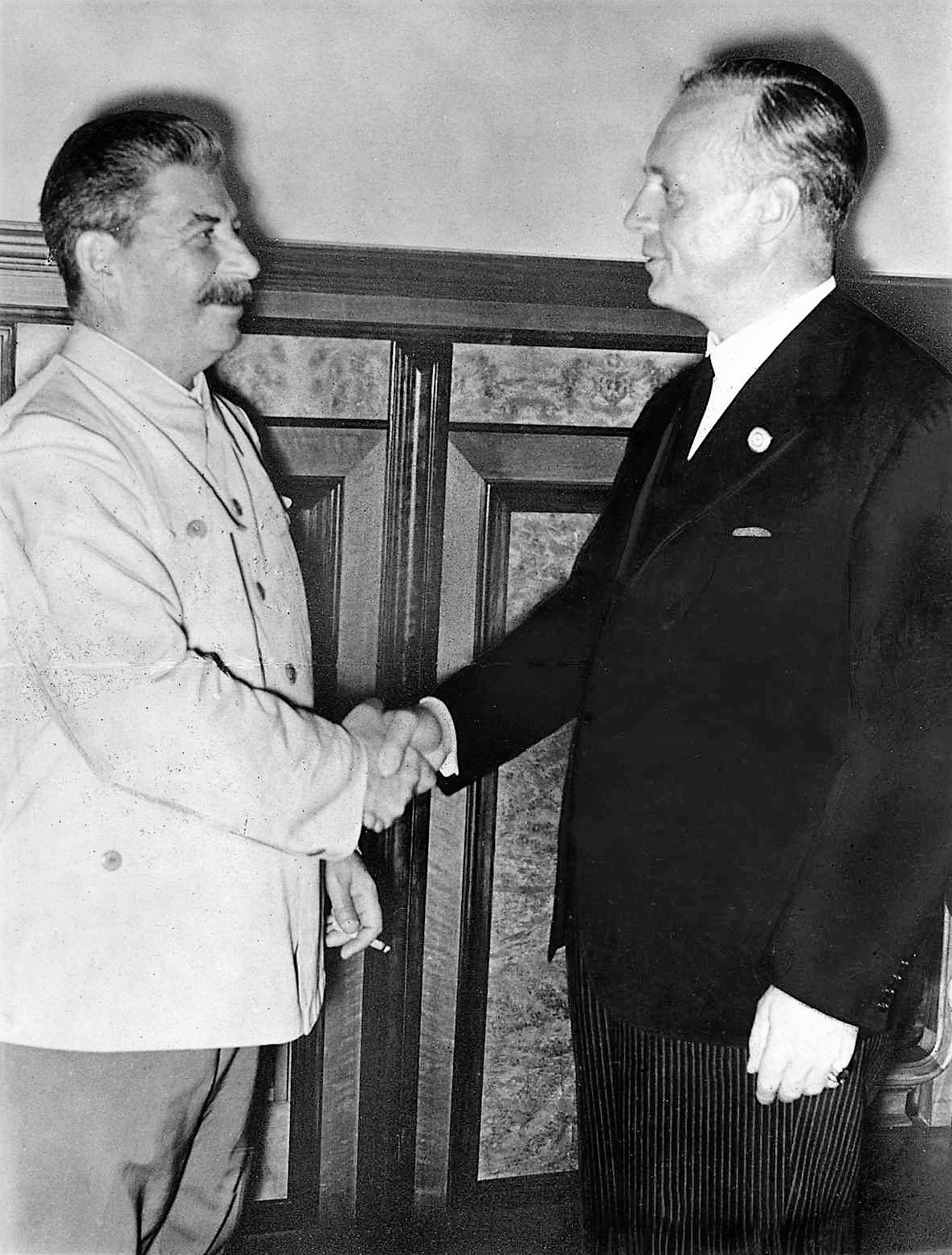

It was only in August, however, when the Soviet leaders realized that the British and the French had not arrived to conduct bona fide negotiations, that the knot was cut and that the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, namely on August 23. This agreement was named the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, after the ministers of foreign affairs, but it was also to become known as the Hitler-Stalin Pact. That such an agreement was concluded hardly came as a surprise: a number of political and military leaders in Britain as well as France had predicted on a number of occasions that the appeasement policy of Chamberlain and Daladier would drive Stalin “into the arms of Hitler.”

Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking hands after the signing of the pact on August 23, 1939 (CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

“Into the arms” is actually an inappropriate expression in this context. The pact certainly did not reflect warm feelings between the signatories. Stalin even turned down a suggestion to include in the text a few conventional lines about hypothetical friendship between the two peoples. Furthermore, the agreement was not an alliance, but merely a non-aggression pact. As such, it was similar to a number of other non-aggression pacts that had been signed earlier with Hitler, for example by Poland in 1934. It came down to a promise not to attack each other but to maintain peaceful relations, a promise that each party was likely to keep as long as it found it convenient to do so. A secret clause was attached to the agreement with respect to the demarcation of spheres of influence in Eastern Europe for each of the signatories. This line corresponded more or less to the Curzon Line, so that “Eastern Poland” found itself in the Soviet sphere. What this theoretical arrangement was to mean in practice was far from clear, but the pact certainly did not imply a partition or territorial amputation of Poland comparable to the fate imposed on Czechoslovakia by the British and the French in the pact they had signed with Hitler in Munich..

The fact that the Soviet Union laid claim to a sphere of influence beyond its borders is sometimes described as evidence of sinister expansionist intentions; however, establishing spheres of influence, either unilaterally, bilaterally, or multilaterally, had long been a widely accepted practice among powers big and not so big, and was often intended to avoid conflict. The Monroe Doctrine, for example, which “asserted that the New World and the Old World were to remain distinctly separate spheres of influence” (Wikipedia), purported to forestall transatlantic new colonial ventures by European powers that might have brought them into conflict with the United States. Similarly, when Churchill visited Moscow in 1944 and offered to Stalin to carve up the Balkan Peninsula into spheres of influence, the intention was to avoid conflict between their respective countries after the end of the war against Nazi Germany.

Hitler was now able to attack Poland without running the risk of having to fight a war against the Soviet Union as well as the Franco-British duo, but the German dictator had good reasons to doubt that London and Paris would declare war. Without Soviet assistance, it was clear that no effective aid could be offered to Poland, so that it would not take long for Germany to defeat the country. (Only the colonels in Warsaw believed that Poland was able to withstand the onslaught of the powerful Nazi hordes.) Hitler knew only too well that the architects of appeasement continued to hope that, sooner or later, he would eventually fulfill their fondest wish and destroy the Soviet Union, so that they were willing to close their eyes to his aggression against Poland. And he was also convinced that the British and the French, even if they declared war on Germany, would not attack in the West.

The German attack against Poland was launched on September 1, 1939. London and Paris still hesitated a few days before they reacted with a declaration of war against Nazi Germany. But they did not attack the Reich while the bulk of its armed forces was invading Poland, as some German generals had feared. In fact, the protagonists of appeasement only declared war on Hitler because public opinion demanded it. In secret, they hoped that Poland would soon be finished, so that “Herr Hitler”could finally turn his attention on the Soviet Union. The war they waged was merely a “phoney war”, as it would rightly be called, a charade in which their troops, who could have virtually walked into Germany, remained inactively ensconced behind the Maginot Line. It is now almost certain that Hitler sympathizers in the camp of the French and possibly also the British appeasers had let it be known to the German dictator that he could use all his military might to finish off Poland without having to fear an attack by the Western powers. (We refer to the books by Annie Lacroix-Riz, Le choix de la défaite. Les élites françaises dans les années 1930, and De Munich à Vichy. L’assassinat de la 3e République.)

The Polish defenders were overwhelmed, and it quickly became obvious that the colonels who ruled the country would have to surrender. Hitler had every reason to believe they would do so, and his conditions would undoubtedly have implied major territorial losses for Poland, especially, of course, in the country’s Western reaches, bordering on Germany. Nevetheless, a truncated Poland would very likely have continued to exist, just as, after its surrender in June 1940, France was to be allowed to continue to exist in the guise of Vichy-France. On September 17, however, the Polish government suddenly fled to neighbouring Romania, a neutral country. By doing so, it ceased to exist because, according to international law, not only military personnel but also members of the government of a country at war must be interned upon entering a neutral country for the duration of the hostilities. This was an irresponsible and even cowardly act, with nefarious consequences for the country. Without a government, Poland effectively degenerated into a kind of no man’s land – a terra nullius, to use juridical terminology – in which the conquering Germans could do as they pleased since there was nobody to negotiate with about the fate of the defeated country.

This situation also gave the Soviets the right to intervene. Neighbouring countries may occupy a potentially anarchic terra nullius; moreover, if the Soviets did not intervene, the Germans would undoubtedly have occupied every square inch of Poland, with all the consequences that this would have entailed. This is why, on that same 17th of September 1939, the Red Army crossed into Poland and started to occupy the eastern reaches of the country, the aforementioned “Eastern Poland.” Conflict with the Germans was avoided because that territory belonged to the Soviet sphere of influence established in the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact. Here and there, German troops that had penetrated to the east of the demarcation line had to withdraw in order to make room for the men of the Red Army. Wherever they made contact, the German and Soviet militaries behaved correctly and observed traditional protocol. This sometimes involved some kind of ceremony, but there were never any common “victory parades.”

Because their government had gone up in smoke, the Polish armed forces that continued to offer resistance were arguably degraded to the level of irregulars, of partisans, exposed to all the risks associated with that role. Most Polish army units allowed themselves to be disarmed and interned by the arriving Red Army, but sometimes resistance was in fact put up, for example by troops commanded by officers hostile to the Soviets. Many such officers had served in the Russian-Polish War of 1919-1921 and had allegedly committed war crimes such as executing POWs. It is widely accepted that such men were later liquidated by the Soviets in Katyn and elsewhere. (Although with respect to Katyn, doubts have recently resurfaced; this theme has been analyzed in great detail in a book by Grover Furr, The Mystery of the Katyn Massacre.)

Many Polish soldiers and officers were interned by the Soviets according to the rules of international law. In 1941, after the Soviet Union became involved in the war and was therefore no longer bound by rules governing the conduct of neutrals, these men were transferred to Britain (via Iran) to take up battle against Nazi Germany again on the side of the Western allies. Between 1943 and 1945, they would make a major contribution to the liberation of a considerable part of Western Europe (a far more tragic lot befell the Polish military who fell into the hands of the Germans). Those who benefited from the occupation of Poland’s eastern territories by the Soviets also included the Jewish inhabitants. They were transferred to the interior of the Soviet Union and thus escaped the fate that would have awaited them if they had still been in their shtetls when the Germans arrived there as conquerors in 1941. Many of them survived the war and were to start a new life afterwards in the US, Canada, and of course Israel.

The occupation of “Eastern Poland” was carried out correctly, that is, according to the rules of international law, so this action did not constitute an “attack” against Poland, as too many historians (and politicians) have presented things, and certainly not an attack in collaboration with a Nazi-German “ally.” The Soviet Union did not become an ally of Nazi Germany by concluding a non-aggression pact with it, and neither did it become an ally on account of its occupation of “Eastern Poland.” Hitler had to tolerate that occupation, but he would certainly have preferred the Soviets not to intervene at all, so that he could have grabbed all of Poland. In England, Churchill publicly expressed his approval of the Soviet initiative of September 17th, precisely because it prevented the Nazis from conquering Poland in toto. That this initiative did not constitute an attack, and therefore not an act of war against Poland, also appeared clearly from the fact that Great Britain and France, formal allies of Poland, did not declare war on the Soviet Union, as they would otherwise certainly have done. And the League of Nations did not impose sanctions on the Soviet Union, which is what would have happened had it considered this an authentic attack against one of its members.

From the Soviet perspective, the occupation of Poland’s eastern reaches signified the recovery of some of its own territory, lost because of the Russian-Polish conflict of 1919-1921. It is true that Moscow had recognized this loss in the Peace Treaty of Riga that put an end to this war in March 1921, but Moscow had continued to look for an opportunity to recover “Eastern Poland,” and in 1939 this opportunity materialized and was seized. One may stigmatize the Soviets for that, but in this case one must also stigmatize the French, for example, for recuperating Alsace-Lorraine at the end of the First World War, since Paris had recognized the loss of that territory in the Peace Treaty of Frankfurt that had put an end to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871.

More important is the fact that the occupation – or liberation, or recovery, recuperation, or whatever one may want to call it – of “Eastern Poland”provided the Soviet Union with an extremely useful asset that, in the jargon of military architecture, is called a “glacis,” that is, an open space that an attacker must cross before reaching the defensive perimeter of a city or fortress. Stalin knew that, regardless of the pact, Hitler would attack the Soviet Union sooner or later, and this attack would in fact take place in June 1941. At that time, Hitler’s host would have to launch its attack from a starting point much farther away from the important cities in the Soviet heartland than would have been the case in 1939, when he had already been eager to start that attack. On account of the pact, the starting blocks for the 1941 Nazi offensive stood several hundred kilometers farther to the west and therefore at a much greater distance from the strategic objectives deep in the Soviet Union. In 1941, the German forces would arrive to within a stone’s throw from Moscow. That means that, without the pact, they would certainly have taken the city, which may have caused the Soviets to capitulate.

Thanks to the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, the Soviet Union not only gained valuable space, but also valuable time, namely the extra time they needed to prepare for a German attack that was originally scheduled for 1939 but had to be postponed until 1941. Between 1939 and 1941, much crucially important infrastructure, above all factories producing all sorts of war materiel, were transferred to the far side of the Urals. Moreover, in 1939 and 1940, the Soviets had an opportunity to observe and study the war that raged in Poland, Western Europe, and elsewhere, and thus to learn valuable lessons about Germany’s modern, motorized, and “lightning-fast” style of offensive warfare, the Blitzkrieg. The Soviet strategists learned, for example, that the concentration of the bulk of one’s armed forces for defensive purposes right at the border would be fatal, and that only a “defense in depth” offered the possibility of stopping the Nazi steamroller. It would be, inter alia, thanks to the lessons learned that way that the Soviet Union would manage – admittedly with great difficulty – to survive the Nazi onslaught in 1941 and eventually to win the war against that mighty foe.

To make it possible to defend Leningrad in depth, a city with vital armament industries, the Soviet Union proposed to neighbouring Finland in the fall of 1939 to swap territories, an arrangement that would have shifted the border of the two countries farther away from the city. Finland, an ally of Nazi Germany, refused, but via the “winter war” of 1939-1940, Moscow eventually managed to achieve this border modification. Because of that conflict, which did amount to an aggression, the Soviet Union was excommunicated by the League of Nations. In 1941, when the Germans attacked the Soviet Union, assisted by the Finns, and were to lay siege to Leningrad during many years, this border adjustment would permit the city to survive this ordeal.

It was not the Soviets but the Germans who had taken the initiative for the negotiations that eventually produced the pact. They did so because they expected to obtain an advantage from it, a temporary but very important advantage, namely the Soviet Union’s neutrality while the Wehrmacht attacked first Poland and then Western Europe. But Nazi Germany also derived an additional benefit from the commercial agreement associated with the pact. The Reich suffered from a chronic penury of all sorts of strategic raw materials, and this situation threatened to become catastrophic when, as was to be expected, a British declaration of war would lead to a blockade of Germany by the Royal Navy. This problem was neutralized by the delivery of products such as petroleum by the Soviets, stipulated in the agreement. It is not clear how crucial those deliveries really were, especially the deliveries of petroleum: not very important, according to some historians; extremely important, according to others. Nevertheless, Nazi Germany continued to rely to a large extent on petroleum imported – mostly via Spanish ports – from the United States, at least until Uncle Sam entered the war in December 1941. In the summer of 1941, tens of thousands of Nazi planes, tanks, trucks and other war machines involved in the invasion of the Soviet Union were still largely dependent on fuel supplied by American oil trusts.

While it is uncertain how important Soviet-supplied petroleum was to Nazi Germany, it is certain that the pact required the German side to reciprocate by supplying the Soviets with finished industrial products, including state-of-the-art military equipment, which was used by the Red Army to upgrade its defenses against a German attack they expected sooner or later. That was a major cause of concern for Hitler, who was therefore keen to launch his anti-Soviet crusade as soon as possible. He decided to do so even though, after the fall of France, Great Britain was far from counted out. Consequently, in 1941, the German dictator would have to wage the kind of war on two fronts that he had hoped to avoid in 1939 thanks to his pact with Moscow, and he would face a Soviet enemy that had become much stronger than he had been in 1939.

Stalin signed a pact with Hitler because the architects of appeasement in London and Paris turned down all Soviet offers to form a common front against Hitler. And the appeasers turned down those offers because they hoped that Hitler would march east and destroy the Soviet Union, a job they sought to facilitate by offering him a “springboard” in the guise of Czechoslovak territory. It is virtually certain that, without the pact, Hitler would have attacked the Soviet Union in 1939. Because of the pact, however, Hitler had to wait two years before he would finally be able to launch his anti-Soviet crusade. This provided the Soviet Union with the extra time and space that permitted its defences to be improved just enough to survive the onslaught when Hitler finally sent his dogs of war to the East in 1941.The Red Army suffered terrible losses but eventually managed to stop the Nazi juggernaut. Without this Soviet success, an achievement described by the historian Geoffrey Roberts as “the greatest feat of arms in world history,” Germany would very likely have won the war, because they would have gained control of the petroleum fields of the Caucasus, the rich agricultural lands of the Ukraine, and many other riches of the vast land of the Soviets. Such a triumph would have transformed Nazi Germany into an inexpungable superpower, capable of waging even long-term wars against anyone, including an Anglo-American alliance. A victory over the Soviet Union would have given Nazi Germany hegemony over Europe. Today, on the continent, the second language would not be English, but German, and in Paris the fashionistas would promenade up and down the Champs Elysees in Lederhosen.

Without the Pact, then, the liberation of Europe, including the liberation of Western Europe by the Americans, British, Canadians, etc., would never have taken place. Poland would not exist; the Poles would be Untermenschen, serfs of “Aryan” settlers in a Germanized Ostlandstretching from the Baltic to the Carpathians or even the Urals. And a Polish government would never have ordered the destruction of monuments honouring the Red Army, as it has done recently, not only because there would have been no Poland and therefore no Polish government, but because the Red Army would never have liberated Poland and those monuments would never have been erected.

The notion that the Hitler-Stalin Pact triggered the Second World War is worse than a myth, it is an outright lie. The opposite is true: the pact was precondition for the happy outcome of the Armageddon of 1939-1945, that is, the defeat of Nazi Germany.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Jacques R. Pauwels is the author of The Great Class War: 1914-1918. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Featured image: Molotov (left) and Ribbentrop (right) at the signing of the Pact (Public Domain)