Hamas’ “Guests” — Table Manners in Israel vs. Arab Traditional Values: The History of Palestinian Solidarity with Jewish Immigrants

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

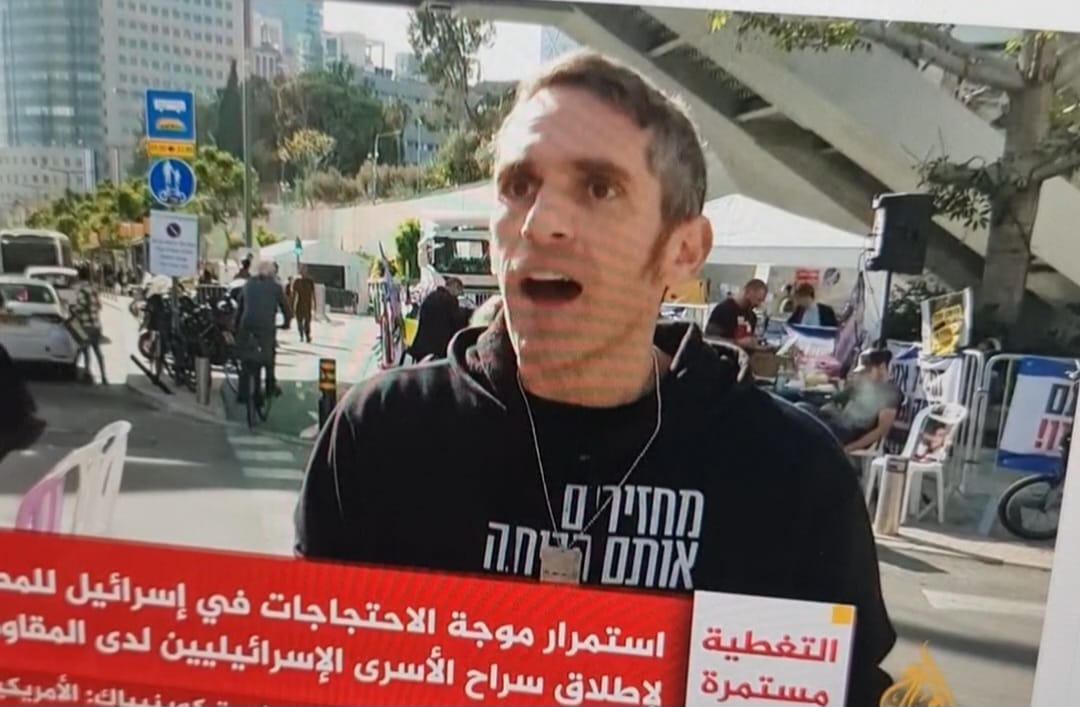

Only a short time prior to listening to Abu Obaidah’s press statement of Dec 21, I had been watching a news report that included a view of the installation of the table set for 200 that was initially organized in Tel Aviv by Mosaic United, the World Zionist Organization and the European Jewish Congress as a symbol of the absent prisoners held by the Palestinian resistance in Gaza. The news report featured an Israeli activist saying, without irony, “because human lives matter.”

What struck me in Abu Obaidah’s statement wasn’t, as you might think, the hypocrisy of such a statement by the activist, a hypocrisy I have come to expect after more than two months of Israeli massacres of Palestinian children and civilians numbered in the thousands. Rather, what struck me was something Abu Obaidah said about a clash of civilizations: “The enemy continues to repeat its foolishness and historical mistakes because it is disconnected from the reality of our people and their civilization.”

The image of the pristine table arrangement in Tel Aviv graphically represents a western settler-colonial reality.

The images of the frenetic scramble for food on top of humanitarian aid trucks by starving Palestinians only increased the grotesqueness of this image below and its associations in my mind.

Installation featuring a table set for 200 in “a pristine Shabbat arrangement” extends across the entire plaza outside the Tel Aviv Museum of Art

In the epic events unfolding horrifically before our eyes in Gaza in ways that often fail words, adherence to tradition and social norms are not confined to interactions with fine china, crystal glasses, and silverware. When the Palestinian resistance called their captives “guests,” anyone familiar with the Arab tradition of hospitality immediately understood what that meant and was not surprised at the testimony of released Israeli captives regarding their good treatment.

Historically, Arab hospitality emerged from the practice of welcoming and providing for desert travelers who passed through towns. The aim was to honor guests and break the ice, eliminating any awkwardness or fear associated with meeting strangers.

Despite hasbara efforts to obscure these facts, it is well documented that Palestinian communities under the British Mandate initially welcomed Jewish immigrants to Palestine, because they recognized their economic contributions and skills.

Palestinian families were hospitable, providing food and shelter to Jewish immigrants who arrived in Palestine with little or no resources, emphasizing a shared humanity. All of this changed when Zionist plans to displace Palestinians and take their land became apparent to a largely agrarian population.

It’s a pity that Zionist invaders in Palestine did not learn from the traditions and values of the land they occupied in 1948, but rather brought with them their own version of Nazi cruelty (the Irgun targeted Palestinian civilians then, just as the “IDF” is targeting them now with much more devastating weapons, even invoking nuclear weapons), thus adopting the colonial values and tactics of their western countries of origin and practicing the same harsh suppression measures introduced by the British in Palestine during the 1936–1939 Palestinian revolt.

Israeli activist: “Because human lives matter …”

The British administration during that time employed various tactics to suppress the Palestinian uprising of 1936–1939. These repressive measures, often conducted with the help of Jewish forces, were intended to intimidate the entire Palestinian population and undermine popular support for the revolt. If you are following Israel’s war on Gaza and its repression tactics these past decades since its establishment, you will recognize the methods I list below immediately:

Mass detentions of Palestinians (“caging a village”) took place with the aid of Zionist intelligence and helped build a network of informants: “Mass detention of male populations during searches — in on-site or semipermanent cages — became commonplace and was often combined with forced labor and other forms of punishment. The scale of detentions and the broad sweep of the population they affected are one of the most dramatic and underexamined aspects of the 1930s counterinsurgency.”

Another “dramatic” measure was that of extra-judicial executions: By summer 1938, “the British reoccupied villages in the Galilee and the central highlands, put the Special Night Squads — notorious units that placed irregular Jewish forces under British officers to carry out raids and extrajudicial executions — into action, and converted the Mandate judicial system into a hanging court for Arabs.”

There were also house demolitions used as a punitive tactic, heightened surveillance and control over Palestinian communities by British and Jewish policemen, house searches without warning or consent, administrative detentions (beatings and imprisonments without formal charges or trial), night raids disrupting lives and instilling fears, torture, deportation, and land confiscations with the confiscated land sometimes allocated for Jewish colonies or other purposes.

Today, Israel by all accounts is following in the footsteps of the imperial superpower of our time in Iraq. I am referring here to US “counterinsurgency” efforts in Iraq in 2003–2006, when the US struggled to mount an effective plan to protect the civilian population and lacked a coherent strategy, which led to intermittent and ineffective tactical approaches without achieving desired outcomes.

In western culture, knowing how to set a table correctly and understanding the proper use of knives and forks is considered a sign of cultural refinement. Think of Downton Abbey or of the many times in movies a character from a “lower-class” background agonizes over the use of knives and forks when thrown into a posh environment. And think also of the smug assumptions some western cinema goers make upon encountering the heartwarming Arab tradition of arranging the family table on the floor using pita bread or flatbread or the right hand to scoop up bites from a communal dish, where simplicity and communal sharing are given priority over elaborate table settings.

Arab culture is a culture that European Zionist Jews regard as inferior, in keeping with what Edward Said calls the “dispossessing movements of modern European colonialism.”

The notion that some cultures were advanced and civilized, others backward and uncivilized; these ideas, plus the lasting social meaning imparted to the fact of color (and hence of race) by philosophers like John Locke and David Hume, made it axiomatic by the middle of the nineteenth century that Europeans always ought to rule non-Europeans.

Imperial table manners are just a veneer. A great deal has been made of Queen Victoria’s “quick thinking and uncommon courtesy” during a diplomatic reception in 19th-century England when she drank from a finger bowl in imitation of the action of an African chieftain, who had no idea of its use. With this gesture, she is said to have “spared her guest from humiliation.” Why an African chieftain should feel humiliated for not being familiar with the table etiquette of a finger bowl is not a mystery. The assumption is that the table manners of the empire are naturally more “civilized” than those of the chieftain’s culture.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

This article was originally published on the author’s blogsite.

Rima Najjar is a Palestinian whose father’s side of the family comes from the forcibly depopulated village of Lifta on the western outskirts of Jerusalem and whose mother’s side of the family is from Ijzim, south of Haifa. She is an activist, researcher and retired professor of English literature, Al-Quds University, occupied West Bank.

She is a regular contributor to Global Research.