France 1939–1945: From Strange Defeat to Pseudo-Liberation

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Global Research Referral Drive: Our Readers Are Our Lifeline

***

Abstract

This essay provides a class-analysis interpretation of France’s role in World War II. Determined to eliminate the perceived revolutionary threat emanating from its restless working class, France’s elite arranged in 1940 for the country to be defeated by its “external enemy,” Nazi Germany. The fruit of that betrayal was a victory over its “internal enemy,” the working class. It permitted installing a fascist regime under Pétain, and this “Vichy-France”—like Nazi Germany—was a paradise for the industrialists and all other members of the upper class, but a hell for workers and other plebeians. Unsurprisingly, the Resistance was mostly working class, and its plans for postwar France included severe punishment for the collaborators and very radical reforms. After Stalingrad, the elite, desperate to avoid that fate, switched its loyalty to the country’s future American masters, who were determined to make France and the rest of Europe free for capitalism. It proved necessary, however, to allow the recalcitrant leader of the conservative Resistance, Charles de Gaulle, to come to power. In any event, the “Gaullist” compromise made it possible for the French upper class to escape punishment for its pro-Nazi sins and to maintain its power and privileges after the liberation.

*

Introduction

In 1914, most if not all European countries were not yet full-fledged democracies but continued to be oligarchies, ruled by an upper class that was a “symbiosis” of the landowning aristocracy (allied with one of the Christian Churches) and a bourgeoisie (i.e., upper-middle class) of industrialists, bankers, and such. Universal suffrage did not even exist yet in Britain or Belgium, so the upper class was firmly in power. In the “lower houses” of parliaments, this elite increasingly had to put up with pesky representatives of socialist (or “social-democratic”) and other plebeian parties, but it managed to maintain control. More importantly, it continued to monopolize non-elected state institutions such as the executive (usually a monarch), the judiciary, the diplomatic corps, the upper houses of parliaments, the higher ranks of the civil service, and above all, the army. (The secret services were only later to become important in this respect.)

The upper class, demographically a tiny minority, was not fond of democracy. After all, democracy means the rule of the demos, that is, the poor and restless majority of the people, the presumably dumb and cruel and therefore frightful “masses.” Particularly distressful for the upper class was the fact that, under the auspices of socialist parties and labor unions, the industrial working class had been agitating successfully for democratic reforms on the social as well as political level, such as a widening of the voting franchise, limitation of the working hours, higher wages, and social services such as paid holidays, pensions, and free or at least inexpensive health care and education.

The Working Class

The working class, then, was the driving force behind the ongoing, seemingly irresistible democratization process. Aristocrats and bourgeois feared that the democratic reforms the labor movement had been able to wrest from them were slowly undermining the established order or, worse, that a collapse of this order could suddenly come about via revolution. Indeed, most working-class parties subscribed to Marxist socialism and championed, at least in theory, the kind of revolution that was to bring about the “great transformation” from capitalism to socialism. The Paris Commune of 1871 and the Russian Revolution of 1905 had provided foretastes of such a cataclysm, and the many strikes and other eruptions of unrest in the years leading up to 1914 loomed like a kind of revolutionary writing on the wall. In this context, war was increasingly seen as the great antidote to revolution and democracy. It is mainly, though not exclusively, for this reason that the European upper class wanted war, prepared for war, and, in 1914, took advantage of a tragic but relatively unimportant incident in the Balkans to unleash war (Pauwels, 2016).

A barricade thrown up by Communard National Guard on 18 March 1871. (From the Public Domain)

As a remedy against the twin threat of revolution and democracy, however, war proved to be counterproductive. First, the “Great War” did not chase away the specter of revolution once and for all.

To the contrary, it ended up triggering revolutions in virtually all belligerent (and even some neutral) nations, and one of those revolutions even triumphed in one of the great empires, Russia. Second, the war produced not less, but more democracy: indeed, in order to take the wind out of billowing revolutionary sails in Britain, Germany, Belgium, and so forth, new, previously unthinkable democratic reforms, such as the introduction of universal suffrage and the eight-hour day, had to be introduced.

After 1918. The Upper Class

After 1918, the upper class managed to remain in control, mostly thanks to its continuing monopoly of non-elected state institutions. But the members of the ruling elite had reasons to be very disgruntled. First, they now had to operate within considerably more democratic parliamentary systems, in which socialist and even communist parties as well as militant labor unions played a role; second, they continued to feel threatened by revolution. Before 1914, revolution had been a specter, but after 1918 it was embodied by the fruit of the Russian Revolution, the Soviet Union. That new state represented a socialist “counter-system” to capitalism and served as source of inspiration and active support for the increasing number of plebeians who pursued revolutionary change à la russe—and also for the growing numbers of colonial subjects who yearned for independence. The evolutionary menace loomed even larger during the great economic crisis of the 1930s, when mass unemployment and misery, a scourge that did not affect the rapidly industrializing Soviet Union, caused even more plebeians to long for radical, revolutionary change.

It is for this reason that the upper class supported fascist, that is, extreme right-wing, anti-democratic movements led by strongmen, men who were prepared to take the kinds of actions of which aristocrats, bankers, and businessmen could expect to benefit: putting an end to all the democratic nonsense; ruthlessly eliminating labor unions and workers’ parties, especially the revolutionary socialists, that is, the communists; and, via a policy of low wages, (re)armament, and imperialist expansion, leading the capitalist economy out of the desert of the Great Depression.

Fascism revealed itself to be the instrument by means of which the upper class, beleaguered by an economic crisis and threatened by a socialist “counter-system,” could again hope to achieve what it had dreamed of in 1914, namely to arrest and even roll back the democratization process and to avoid revolutionary change—and also to achieve imperialist objectives, but that is a different story (see Pauwels 2019b). In just about all European countries, the upper class first supported fascist movements financially and otherwise, then took full advantage of its control over the army, the state bureaucracy, etc., to replace the liberal-democratic systems with fascist regimes. It started already in Italy in 1922, but the upper class’s greatest triumph was to come in 1933 in Germany, where Hitler was hoisted into the saddle of power to the great satisfaction of bankers, industrialists, aristocratic landowners, generals, and Catholic and Protestant prelates.

The supposedly democratic “Western” elites applauded these fascist coups d’état: Churchill, for example, loudly praised Mussolini, and the Duke of Windsor functioned as a cheerleader for Hitler. Hitler, the most ruthless of all fascist dictators, even became the “great white hope” of the Western upper class. He was expected to use the military might of the Reich to crush the Soviet Union, the fruit of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the perceived seedpod of future revolutions at home and in the colonies. Thus, he would achieve the goal they themselves had vainly pursued by means of armed interventions in support of the reactionary “Whites” against the revolutionary “Reds” in the Russian Civil War in 1918–1919.

In some countries, however, the “filofascist” plans of the upper class went awry, most dramatically so in France, where in 1934 an embryonic coup d’état failed miserably. Ironically, this attempt yielded the opposite of what the elite had hoped for: the formation of a “popular front,” a leftist coalition government that introduced a package of far-reaching social reforms, including higher wages, the 40-hour work week, collective bargaining, the legal right to strike, and paid vacations. This undeniably democratic achievement was detested by industrialists, bankers, and employers in general, because it implied a (modest) redistribution of wealth in favor of the wage-earning plebs and was perceived as a harbinger of deeper reforms to come.

To understand what happened afterwards, including the “strange defeat” of France in 1940, one must read the books of historian Annie Lacroix-Riz, professor emerita at Université Paris 7. In her Le choix de la Défaite: les élites françaises dans les années 1930 (Lacroix-Riz, 2006), and De Munich à Vichy, l’assassinat de la 3e République 1938–1940 (Lacroix-Riz, 2008), she demonstrated that in May–June 1940, when Germany attacked in the west, the French political and military leaders deliberately failed to put up the kind of resistance of which their army was certainly capable, thus making defeat inevitable.

By doing so, they sought to achieve the objective they had pursued in vain in 1934, that is, the advent to power of a fascist, or quasi-fascist, strongman like Mussolini, Franco, or Hitler. They did not particularly like to be defeated by the external enemy, Germany, but that “strange defeat,” as it was to be called by historian Marc Bloch in a book published in 1946, allowed them to achieve a victory against their internal enemy, the leftist labor movement. Being defeated by the fascist Reich made it possible to smuggle fascism into France via the back door, so to speak; it allowed them to replace France’s “Third Republic,” much too democratic to their taste, with a dictatorship tailor-made to defend and promote their interests.

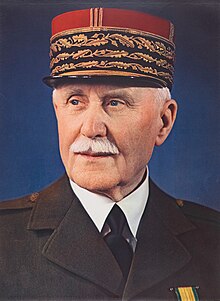

Marshal Pétain

And indeed, France’s military collapse permitted a strong leader to descend on the stage like a deus ex machina. It happened to be the same personality that had been waiting in the wings in 1934, namely Marshal Philippe Pétain, arguably not a fascist himself but certainly an arch-conservative philofascist.

Image: Philippe Pétain (From the Public Domain)

The “Vichy France” over which Pétain presided, with Hitler breathing down his neck, was an extremely undemocratic system, but for the country’s upper class it was a paradise, especially for the bankers, industrialists and “employers” (le patronat) in general, as Annie Lacroix-Riz has shown in another book of hers, Industriels et banquiers sous l’Occupation (Lacroix-Riz, 2013).

They were delighted that, just as in Hitler’s Germany, labor unions and working-class parties were eliminated, wages were lowered considerably, and the social reforms introduced by the Popular Front were abolished. Profits rose, not merely because labor costs were minimized: highly profitable business could be done with France’s Nazi overlords, especially as the war dragged on and Hitler ordered plenty of trucks and tanks from French manufacturers such as Renault.

The Nazis also purchased lots of French luxury products such as perfumes and fine wines, including Champagne and grands crus from Bordeaux and Burgundy, as well as Cognac. Some looting did occur, for example, during the fighting in the spring of 1940, but looting was the exception, while the general rule was that the Nazis purchased these goods, and at inflated prices. They paid with Francs extorted from Pétain’s collaborator regime based in Vichy under the terms of the French capitulation of June 1940. The taxes squeezed out of ordinary Frenchmen by the Petain regime thus found their way via German buyers—the armed forces, the SS and other Nazi Party organizations, wine merchants, and so forth—into the wallets of rich producers and distributors of wines and perfumes. This sad saga has been related in detail in Christophe Lucand’s recent (2019) book, Hitler’s Vineyards: How the French Winemakers Collaborated With the Nazis. The myth that the Nazis’ efforts to loot French wines were mostly thwarted by smart and patriotic vintners and dealers, concocted by the latter at the end of the war, was promoted in a book published in 2001 by two American journalists, Don and Petie Kladstrup, Wine and War: The French, the Nazis and the Battle for France’s Greatest Treasure (Kladstrup & Petie, 2001).

As for the Catholic Church, its French prelates were tickled pink that Pétain buried the anticlerical republic and resurrected the country’s intimate relationship with Catholicism, personified by Joan of Arc, which had fallen victim to the Revolution of 1789. Not surprisingly, the Pope blessed Pétain just as eagerly as he had blessed Mussolini, Franco, and even Hitler.

Last but not least, all “pillars” of the French establishment rejoiced that the menace of revolution had seemingly evaporated forever. Indeed, communism—that is, revolutionary socialism—was emasculated domestically as the communist party was outlawed. Moreover, communism also looked doomed internationally when, in June 1941, Hitler finally launched his great crusade against its Mecca, the Soviet Union, a crusade that had been eagerly anticipated, and was to be actively supported, by the French elite.

The Vichy Regime

The Vichy regime benefited the upper class but was catastrophic for the working class and for ordinary people in general, who had to put up with a precipitous 50 % drop in wages between 1940 and 1945, longer working hours, poorer food, more industrial accidents and diseases such as tuberculosis, and higher prices. Even vin ordinaire became extremely expensive as the Nazis also made massive purchases of plonk and suppliers took advantage of the opportunity to raise prices.

Not surprisingly, the choice between collaboration and Resistance—or, for that matter, sitting on the fence, known as “attentisme”—was not a matter of individual choice, of psychology, but of class, of sociology.

It is hardly surprising that the French working class provided the bulk of the resisters, because they had every reason to hate the Vichy system and its Nazi patrons; the collaborators, on the other hand, were predominantly of upper-class background, because they were delighted with a system they had in fact imported into the country via the “strange defeat.”

While workers joined the Resistance, which turned out to be not exclusively but “mostly working-class and communist,” as Lacroix-Riz emphasizes, businessmen and bankers, army generals, high-ranking officials of the police and the state bureaucracy, judges, university professors, prelates of the Catholic Church, and so forth, proved loyal to Marshal Pétain, benevolent towards the Germans, and hostile towards the enemies of Nazi Germany. These enemies included the British, the Soviets, and all shades of the Resistance, first and foremost the communists but also the non-communist, conservative but patriotic resisters such as General de Gaulle, leader of the “Free French” forces based in Britain. Under the auspices of Vichy, the French upper class—whose members, female as well as male, were often seen hobnobbing with SS officers in Maxim’s and other Parisian hotspots (d’Almeida, 2008)—eagerly helped the Germans to hunt down, imprison, torture, and execute resisters; they also assisted in sending French workers to Germany to serve as slave laborers, and in deporting Jews, anti-Franco Spanish refugees, and other “undesirables” to concentration camps. The Resistance responded with sabotage and assassinations of leading collaborators and German military, for which the Germans and/or the Vichy authorities often exacted a terrible revenge, for example, by taking

and executing hostages.

As seen from the perspective of France’s upper class, the humiliating defeat of 1940 brought subordination of their country to a foreign power, to an “external enemy.” That may have been unpleasant to many aristocrats and bourgeois members of the upper class, but it was a minor nuisance in comparison to the fact that this defeat signified a triumph of their class against their “interior enemy,” the working class. Thanks to the Nazis, the upper class was able to get rid of the democratic system of the Third Republic and of the revolutionary menace embodied by the communists. That Nazi Germany was now in control of all or most of Western as well as Central Europe did not constitute a problem for them; to the contrary, it was a blessing. Nazi Germany was henceforth perceived as the guardian angel of the upper class in France and all of Europe. And when the mighty, supposedly invincible Wehrmacht attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, it was confidently expected that its inevitable victory would guarantee that Germany would rule all of Europe for an indefinite period of time; under Nazi auspices, the upper class in France and throughout Europe would thus be able to rule forever over a chastened, disciplined, and docile lower class.

But a dark lining started to stain this silver cloud as early as July 1941. French generals, meeting in Vichy that month, discussed confidential reports received from German colleagues about the situation on the eastern front, where the German advance was going well, but not nearly as well as expected; they came to the conclusion that Germany was unlikely to defeat the Red Army and would in all likelihood end up losing the war. The major setback suffered by the Wehrmacht in early December 1941 in front of Moscow by a powerful Red Army counterattack, coupled with the entry into the war of the US, caused even more cognoscenti in France (and elsewhere) to doubt that Germany could still win the war. After the British-American landings in French North Africa in November 1942 and particularly after the crushing German defeat at Stalingrad in the winter of 1942–1943, just about every Frenchman knew that Nazi Germany was doomed. That also meant that the Soviet Union was about to emerge from the war as the great victor, likely to wield unprecedented prestige and influence throughout Europe and, horribile dictu, in the colonies, where its achievement electrified independence movements. As far as France was concerned, it meant that the country’s upper class would be orphaned of its German tutor; that the class conflict reflected by the collaboration-Resistance dichotomy would end with a triumph of the resisters; that the victors would exact terrible revenge for the crimes of the collaborators; and that upper-class rule would collapse in a blaze of socializations and other revolutionary changes.

Except for a hard core of fanatical French fascists who were to remain loyal to Pétain and Hitler until the end, and underlings who remained unaware that “the times were a-changing,” the French upper class discreetly went to work to avoid this terrifying scenario. Bankers, industrialists, generals, high-ranking policemen and bureaucrats such as prefects and colonial governors, judges, university professors and other public- and private-sector patricians who had been directly or indirectly involved in the treason of 1940 and the murderous policies of the Vichy Regime and the Nazis, and had profited from collaboration, discreetly started to distance themselves from their Nazi overlords. They prepared for what loomed increasingly like the only alternative to a Soviet future for France, namely the nation’s subordination to the US. They hoped that the German occupation of France would be followed by an occupation by the Americans, from whom they could expect salvation; and this expectation was not unfounded

(Lacroix-Riz, 2014, pp. 104-110; Lacroix-Riz, 2016, p. 245ff).

The political, economic and military elite of the US had nothing against fascism, not even against its German variant, Nazism. After all, Hitlerite antisemitism and racism in general were not perceived as particularly objectionable in a country where “white supremacy” was alive and well. Moreover, Nazism and all other shades of fascism were deadly enemies of the number one foe of the American elite, namely communism.

Washington, which had prepared plans for war against Japan, but not Germany (Rudmin, 2006), had involuntarily “backed into” the war against Germany. It had done so after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which was followed by a totally unexpected declaration of war on the US by Hitler. A few days before Pearl Harbor, on the day the Soviets launched a counter-offensive in front of Moscow, Hitler had been informed by his own generals that he could no longer expect to win the war. By gratuitously declaring war on the US, he hoped, in vain as it turned out, to lure the Japanese into declaring war on the Soviet Union, which might have revived the prospect of a German victory in the “Eastern War.” Tokyo did not take the bait, but the result was that, undoubtedly to the surprise and even shock of its political and military leaders, the US was now formally an enemy of Germany—and an ally of the Soviet Union.

The alliance with the Soviets was based solely on facing a common enemy and was therefore unlikely to survive that enemy’s defeat, after which Washington was likely to resume its hostile stance vis-à-vis the Soviets. Even as they were fighting the Nazis and other fascist regimes, such as Mussolini’s Italy, American leaders sought ways to limit any advantages the Soviet Union might gain from being the major contributor to the common triumph. This strategy involved leaving it to the Red Army to do most of the fighting and suffer the bulk of the sacrifices required to defeat the mighty Nazi behemoth. It was hoped that, at war’s end, the Soviet Union would thus prove too weak to prevent America from establishing its hegemony in the liberated countries of Europe and in defeated Germany. And under US auspices it would be strictly verboten for the population to bring about radical, and certainly revolutionary changes, even when such changes were desired by resistance movements that enjoyed widespread popular support, as in the case of France.

Philippe Pétain meeting Hitler in October 1940 (Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

The Role of US Banks and Corporations

Washington was determined to save a capitalist system that, in Europe, had been thoroughly discredited by the Great Depression of the 1930s and by its intimate association with Nazi Germany and collaborator regimes such as Vichy.

Saving the established capitalist order in general, and saving the big banks and corporations that happened to be the stars of the capitalist universe, loomed all the more important in the minds of the US leaders since America’s own banks and corporations happened to have plenty of branch plants and other investments as well as lucrative partnerships in Nazi Germany and occupied countries (Pauwels, 2017, part two).

The latter included France, where subsidiaries of US banks and corporations, such as the branch plant of Ford, flourished thanks to collaboration with the Nazis. These firms, which had eagerly involved themselves in profitable and sometimes criminal collaboration, were extremely likely to fall victim to socializations in case liberation from Nazi and Vichy-rule might trigger revolutionary changes. This would have been a catastrophe for the stateside owners, managers, and shareholders, who happened to be extremely influential in Washington (Pauwels, 2015, chapters 20 and 21).

After Pearl Harbor, the American leaders were officially opposed to German and all other forms of fascism and they were allied with Soviet communism. But behind this anti-fascist façade they remained hostile to the Soviets and communists in general, including the countless communists active in the Resistance movements, and extremely indulgent towards fascists, anti-communists like themselves. The Americans also worked hard, discreetly or openly, to save the skin of the European elites that had supported fascist movements, brought fascists to power in Germany and elsewhere, profited from their socially regressive policies and wars of conquest, and, all too often, had helped them to commit terrible crimes—or looked the other way when

these crimes were being committed (Pauwels, 2015, chapter 22).

In this context we can understand why Washington considered the collaborationist government in Vichy to be legitimate and maintained diplomatic relations with it; they were only terminated (by Vichy) in January 1943, after the allied landings in North Africa of November of the previous year. The US authorities, including president Roosevelt, hoped that Pétain himself or some other Vichy personality not overly discredited by collaboration—such as Weygand or Darlan—would stay in power after the liberation, possibly after a purge of its most rabid pro-German elements and the application of a veneer of democratic varnish on a Vichy system that essentially functioned as the political superstructure of France’s capitalist social–economic system.

We can also understand how, conversely, increasing numbers of Vichy collaborators proved themselves eager to switch from the German to the American bandwagon. An American occupation of France would forestall “disorders,” meaning the kind of revolutionary changes planned by the Resistance, would make it possible for their pro-Nazi sins to be forgiven and forgotten, and would enable them to continue to enjoy their power and privileges, not only those they had traditionally enjoyed but also many if not most of those bestowed on them by Vichy.

Under the auspices of the new American masters, France would be a “Vichy without Vichy.” Contacts between the two parties with an interest in an “American future” for France were discreetly established via the Vatican as well as US consulates in Algeria and other French colonies in Africa, in Franco’s Spain, and in Switzerland. The Swiss capital, Berne, served as the crow’s nest whence Allen Dulles, agent of the American secret service OSS, forerunner of the CIA, observed developments in occupied countries such as France and Germany. Dulles, a former New York lawyer with plenty of clients and other connections in Nazi Germany, was in touch with conservative civil and military members of the Reich’s filofascist upper class, that is, the bankers, big businessmen, generals, etc. who had brought Hitler to power in 1933. They had done so, in a context of economic crisis and what seemed to be a revolutionary threat, to save the Reich’s established social–economic order, which was—and was to remain—a capitalist order (see for example, Pauwels, 2017, pp. 63–65), and they had profited handsomely from Hitler’s elimination of the working-class parties and unions, regressive social policies, armament program, war of aggression, and assorted crimes, including the despoliation of Germany’s Jews. Like their counterparts in France, these folks were also hoping that Uncle Sam would intervene to save them and the capitalist system from perishing after an ineluctable Soviet victory.

Nazi Germany was a capitalist Germany, Vichy France was a capitalist France.

The US, the most capitalist of all capitalist countries, was determined to save capitalism in both. Vichy also represented collaboration, which was despised by most Frenchmen, but the Americans were prepared to forgive the sins of all but the most discredited collaborators. The Resistance was a different kettle of fish. On account of its mostly working-class character and the communist ascendancy within the movement, the Resistance was associated with radical and even revolutionary changes—such as socializations—and therefore with anti-capitalism. (The reforms planned by the Resistance were codified in the “Charter of the Resistance” of March 1944; they called for “the introduction of a genuine economic and social democracy, involving the expropriation of the big economic and financial organizations” and “the socialization [le retour à la Nation] of the [most important] means of production such as sources of energy and mineral wealth, and of the insurance companies and great banks.”) (“1944: Charte du Conseil National de la Résistance,” 1944) For this reason, the US authorities hated the Resistance almost as much as Vichy did.

Charles de Gaulle

Of course, there also existed a non-radical Resistance. It was personified by a conservative general, Charles de Gaulle, head of the “Free French” and based in England, but because of his patriotism he also enjoyed considerable prestige and influence in Resistance circles within France. But the Americans detested de Gaulle. They shared Vichy’s view that the general was a front for the communists, a kind of Kerensky who, if he ever came to power, would simply pave the way for a “Bolshevik” takeover.

In France, the German occupation authorities were very much aware that the rats were abandoning the doomed Vichy ship. With the exception of the most fanatic among them, they proved to be indulgent because they knew that in the Reich itself preparations were being made for an “American future” and that not only leading bankers, industrialists, bureaucrats, and generals, but even bigwigs of the Nazi Party, including the SS and Gestapo, were in touch with sympathetic Americans such as Dulles. In Germany itself, leading members of the upper class who had been intimately involved with the Nazi party, such as the banker Hjalmar Schacht, would even be allowed to morph into “resisters” by being locked up in concentration camps such as Dachau, where they were accommodated in separate, comfortable quarters and well treated. In similar fashion, the German authorities in France were kind enough to arrest numerous high-profile collaborators and deport them to the Reich. There they awaited the end of the war, ensconced in the comfort of a VIP “detention center,” for example a resort hotel on the banks of the Rhine or in the Bavarian Alps. Waving such a “certificate of Resistance,” they could masquerade as patriotic heroes upon their return to France in 1945.

When the French upper class betrayed the nation in 1940 to install a fascist regime under Nazi-German auspices, “a French leader acceptable to the German overlord” was already waiting in the wings, namely Pétain. Selecting a leader for the soon-to-be-liberated France, acceptable to the nation’s new American master, proved to be less easy. As already mentioned, Charles de Gaulle, in retrospect the most obvious candidate for the position, did not meet the criteria because he was suspected of being a front for the communists. It was only on October 23, 1944, that is, several months after the landings in Normandy and the beginning of the liberation of the country, that de Gaulle was officially recognized by Washington as the head of the provisional government of the French Republic.

That had become possible on account of three factors. First, the Americans finally realized that the French people would not tolerate that, after the departure of the Germans, the Vichy system would be maintained in any way, shape, or form. Conversely, they had come to understand that de Gaulle was popular and enjoyed the support of a considerable segment of the Resistance. They therefore needed him to “neutralize the communists at the end of the hostilities.” Second, de Gaulle appeased Roosevelt by committing himself to pursue a “normal” political course that would in no way threaten the “economic status quo.” To underscore and even guarantee his commitment, countless “recycled” Vichy collaborators who enjoyed the favors of the Americans were integrated into his Free French movement and even given leading positions. (This did not go unnoticed by the Soviets, and Stalin expressed his concern that de Gaulle was being “surrounded by Vichy defectors.”) Third, the head of the Free French, who had earlier flirted with Moscow, distanced himself from the Soviet Union, albeit never enough to satisfy Washington. This move also constituted a response to the Soviets’ dim view of the military contribution of the Free French to the common anti-Hitler struggle, their unwillingness to admit France to the circle of the victors, the “Big Three,” and their lack of support for de Gaulle’s planned restoration of the French colonial empire, especially Indochina (Magadeev, 2015).

Gaullism thus became respectable and de Gaulle himself morphed into “a right-wing leader,” acceptable to the French upper class as well as the Americans, successors to the Germans as “protectors” of the interests of that elite.

Image: A WWII photo portrait of General Charles de Gaulle (From the Public Domain)

These undertakings made it possible for the general to be anointed by the Americans, albeit very belatedly and without any enthusiasm. At the time of the landings in Normandy, they were not yet prepared to do so and were poised to administer liberated France themselves. But things changed when, at the end of August 1944, Paris was about to be liberated and the possibility arose that in the French capital the communist-dominated Resistance might form a government. Suddenly, the Americans deemed it necessary to rush de Gaulle to the scene to present him as the savior for whom patriotic France had been waiting for four long years. They made it possible for him to strut triumphantly down the Champs Elysees, while forcing the local Resistance leaders to follow him at a respectful distance, looking like unimportant extras.

It was probably at that time that Washington realized that a government led by de Gaulle was the only alternative to a government controlled by the left-wing, communist-dominated non-Gaullist Resistance, a government that was likely to introduce the kind of radical reforms that American leaders, including president Roosevelt, equated with a “red revolution.” On October 23, 1944, Washington finally officially recognized de Gaulle as leader of the provisional government of liberated France.

Under the auspices of de Gaulle, France replaced the Vichy system with a new, democratic political superstructure, the “Fourth Republic.” (That system was to give way to a more authoritarian, American-style presidential system, the “Fifth Republic,” in 1958.) The working class, which had suffered so much under the Vichy regime, was treated to a package of benefits including higher wages, paid holidays, health and unemployment insurance, generous pension plans, and other social services; in short, a kind of “welfare state,” modest in many ways, but a genuine “workers’ paradise” in comparison with the unbridled capitalist system of the US, devoid of even the most elementary social services. The introduction of these benefits also purported to retain the loyalty of ordinary Frenchmen in the face of the postwar competition with the Soviet Union, the country that most Frenchmen credited with having defeated Nazi Germany and which many admired for its achievements on behalf of the working class.

All these measures benefited from widespread support of wage-earning plebeians but, because they hardly favored capital accumulation, were resented by the upper class, and especially by the patronat, the employers, who had to help subsidize this “welfarism.” On the other hand, the ruling elite appreciated that these reforms appeased the working class, thus taking the wind out of the revolutionary sails of the communists, even though the latter found themselves at the height of their prestige because of their leading role within the Resistance and their association with the Soviet Union, then still widely credited in France as the vanquisher of Nazi Germany. Then again, in order to avoid conflict with its American and British allies, Moscow had instructed the French Communist Party as early as March 1944 not to prepare for revolutionary action.

The women and men of the Resistance were officially elevated to hero status, as monuments were erected and streets named in their honor. Conversely, collaborators were officially “purged,” and their most infamous representatives were punished; some of them—for example the sinister Pierre Laval—even received the death penalty, and leading economic collaborators, such as the car manufacturer Renault, were nationalized. But with his provisional government full of recycled Vichyites and Uncle Sam looking over his shoulder, de Gaulle ensured that only the most high-profile bigwigs of the Vichy regime were purged, as Annie Lacroix-Riz demonstrates in her most recent book (Lacroix-Riz, 2019).

Many if not most of the collaborationist banks and corporations owed their salvation to an American connection, for example Ford’s French subsidiary. Death sentences were frequently commuted, and Nazi occupation officials (such as Klaus Barbie) and collaborators who had committed major crimes were spirited out of the country to a new life in South or even North America by France’s new American overlords, who appreciated the anti-communist zeal of these men. Countless collaborators got off the hook because they managed to produce fake “Resistance certificates” or suddenly developed diseases that caused their trials to be postponed and eventually dropped. Local officials guilty of working with and for the Germans escaped retribution by being transferred to a city where their collaborationist past was unknown, for example, from Bordeaux to Dijon. And most of those who were found guilty received only a very light punishment, a mere slap on the wrist. All of this was possible because de Gaulle’s government, and its Ministry of Justice in particular, teemed with unrepentant former Vichyites; unsurprisingly, they were what Lacroix-Riz calls “a club of passionate opponents of a purge” (un club d’anti-épurateurs passionnés).

While France’s upper class had to put up again, as before 1940, with the inconveniences of a democratic parliamentary system in which plebeians were allowed to provide some input, it managed to remain firmly in control of the post-war French state’s non-elected centers of power, such as the army, the judiciary, and the high ranks of the bureaucracy and the police, centers which it had always monopolized. Vichy generals, for example, mostly known to have been enemies of the Resistance who had conveniently converted to Gaullism, retained control over the armed forces, and countless officials who had been diligent servants of Pétain or the German occupation authorities remained in office and were able to pursue prestigious careers and benefit from promotions and honors. Annie Lacroix-Riz concludes that the supposedly “law-abiding state” (État de droit) of de Gaulle “sabotaged the purge of the [collaborationist] high-ranking officials, thus. . . .allowing the survival of a Vichy hegemony over the French judicial system”—and, one might add, the survival of a Vichy-style system in general.

In 1944–1945, the French upper class did not atone for its collaborationist sins, and it was lucky that the revolutionary threat to its capitalist social–economic order, embodied by the Resistance, could be exorcized through the introduction of a system of social security. The bitter wartime class conflict between France’s patricians and plebeians, reflected in the dichotomy of collaboration-resistance, was thus not really terminated, but merely yielded a truce. And that truce was essentially “Gaullist,” since it was concluded under the auspices of a personality who was conservative enough for the taste of the French upper class and its new American “tutors,” but whose sterling patriotism endeared him to the Resistance and its constituency.

De Gaulle collaborated with Washington to prevent the radical reforms which the Resistance had planned and many if not most Frenchmen had expected and would have welcomed.

After the war, however, he proved himself to be not nearly as pliant a vassal in the context of the Pax Americana the US imposed on “liberated” Western Europe as, for example, Konrad Adenauer in Germany and the postwar leaders of Italy, Belgium, etc. He refused, for example, to allow the American armed forces to ensconce themselves indefinitely on French soil, as they did in Germany, Italy, and the Low Countries (Gaja, 1994, pp. 332–333). It is for that reason that the CIA very likely orchestrated some of the coups and assassination attempts directed against the regime and/or person of the recalcitrant French president (Blum, 2012, pp. 130–132).

After the death of de Gaulle and, more importantly, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the French upper class ceased to see the need to maintain the system of social services it had only adopted reluctantly, and which functioned as an annoying impediment to capital accumulation.

The task of dismantling the French “welfare state,” undertaken under the auspices of pro-American presidents such as Sarkozy and now Macron, was facilitated by the de facto adoption by the European Union of neoliberalism, an ideology advocating a return to unfettered laissez-faire capitalism à l’américaine.

The class warfare that had pitted collaboration against Resistance during World War II was thus restarted, as reflected in the recent weekly demonstrations by the “yellow vests.” Whether this situation will be alleviated or exacerbated by the Coronavirus crisis remains to be seen.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Dr. Jacques R. Pauwels was born in Belgium in 1946, moved to Canada in 1969. Undergraduate history studies at Ghent University, Phd in history from York University in Toronto; MA and PhD in Political Science from University of Toronto. Part-time lecturer in history at various universities in Ontario from approximately 1975 to 2005.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Sources

1944: Charte du Conseil National de la Résistance, 1944. Retrieved from http://www.ldh-france.org/1944-CHARTE-DU-CONSEIL-NATIONAL-DE.

Blum, W. (2012). Killing Hope: U.S. Military and C.I.A. Interventions since World War II (2nd ed.). Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press.

d’Almeida, F. (2008). La vie mondaine sous le nazisme. Paris: Perrin.

Gaja, F. (1994). La filosofia del bombardemanto. La storia da riscrivere. Milan: Maquis.

Kladstrup, D., & Kladstrup, P. (2001). Wine and war: The French, the Nazis and the Battle for France’s greatest treasure. New York: Broadway Books.

Lacroix-Riz, A. (2008). De Munich à Vichy, l’assassinat de la 3e République 1938–1940. Paris: Armand Colin.

Lacroix-Riz, A. (2006). Le choix de la Défaite: Les élites françaises dans les années 1930. Paris: Armand Colin.

Lacroix-Riz, A. (2013). Industriels et banquiers sous l’Occupation. Paris: Armand Colin.

Lacroix-Riz, A. (2014). Aux origines du carcan européen 1900–1960. Paris: Delga.

Lacroix-Riz, A. (2016). Les élites françaises entre 1940 et 1944. De la collaboration avec l’Allemagne à l’alliance américaine. Paris: Armand Colin.

Lacroix-Riz, A. (2019). La non-épuration en France: De 1943 aux années 1950. Armand Colin: Malakoff.

Lucand, C. (2019). Hitler’s vineyards: How the French winemakers collaborated with the Nazis. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military (Originally published in French as Le vin et la guerre. Comment les nazis ont fait main basse sur le vignoble français, Malakoff, Armand Colin, 2017.).

Magadeev, I.. France in the Soviet foreign policy, 1943–45, Conference Paper, July, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313304058_France_in_the_Soviet_foreign_policy_1943-45.

Pauwels, J. R. (2015). The myth of the good war: America in the Second World War, revised edition. Toronto: James

Lorimer.

Pauwels, J. R. (2016). The Great Class War 1914-1918. Toronto: James Lorimer.

Pauwels, J. R. (2017). Big business and Hitler. Toronto: James Lorimer.

Pauwels, J. R. (2019). First world war and imperialism. In I. Ness & Z. Cope (Eds.), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of imperialism and anti-imperialism. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rudmin, F.. (2006). Secret war plans and the malady of American militarism. Counterpunch, 13:1, pp. 4–6. Retrieved from http://www.counterpunch.org/2006/02/17/secret-war-plans-and-the-malady-of-american-militarism.