‘It Is Disease that Makes Health Sweet and Good’

How Heraclitus, the Riddler, may teach us to fight Covid-19

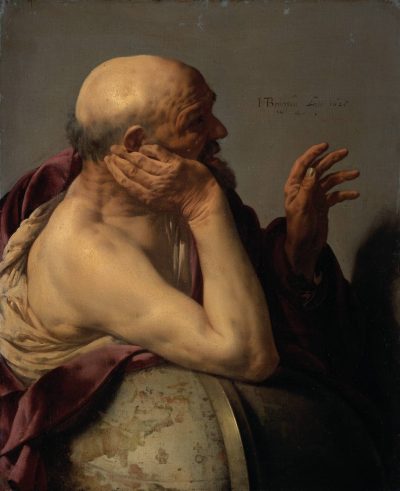

He was known as “the Riddler.” Even “the Dark.” Heraclitus of Ephesus was one of a kind.

In his heart of hearts a contemptuous aristocrat, this master of paradox despised all so-called wise men and the mobs that adored them. Heraclitus was the definitive precursor of social distancing.

We, unfortunately, owe the “pre-Socratic” reductionist label to 19th century historians, who sold to modernity the notion that these thinkers were not so preeminent because they lived before Socrates (469-399 B.C.) throughout the 6th and 5th century B.C., in assorted latitudes found in today’s Greece, Italy and Turkey.

Yet Nietzsche nailed it: the pre-Socratics invented all the archetypes of all the history of philosophy. And if that was not enough, they invented science as well. Their Grandmaster Flash was, unequivocally, Heraclitus.

Perpetual detective story

Only around 130 fragments of Heraclitus’s thinking managed to survive – prefiguring Walter Benjamin’s intuition that the beauty of knowledge is encapsulated by the fragment.

Let’s start with “Nature loves to hide.” Heraclitus established that nature and the world are ambiguous par excellence, in a never-ending film noir. As nature is a nest of riddles, he could only use riddles to examine it.

It’s tempting to imagine Heraclitus as a doppelganger of the famous Delphic oracle, which “neither declares nor conceals, but gives a sign.” He’s certainly a precursor of Twin Peaks (the owls are not what they seem). Legend has it that the only copy of his book was consigned to a temple in Ephesus in the early 5th century B.C., shortly after the death of Pythagoras, so the mobs wouldn’t have access to it. Heraclitus, a member of the Ephesus royal family, would not have settled for less.

So we, as a race, are essentially a misguided bunch.

“Men are deceived in the recognition of what is obvious, like Homer who was wisest of all the Greeks,” Heraclitus wrote. “For he was deceived by boys killing lice who said: ‘What we see and catch we leave behind; what we neither see nor catch we carry away.’”

Heraclitus compared our lot to beasts, winos, deep sleepers and even children – as in, “Our opinions are like toys.” We are incapable of grasping the true logos.

History, with rare exceptions, seems to have vindicated him.

There are two key Heraclitus mantras.

1) “All things come to pass according to conflict.” So the basis of everything is turmoil. Everything is in flux. Life is a battleground. (Sun Tzu would approve.)

2) “All things are one.” This means opposites attract. This is what Heraclitus found when he went tripping inside his soul – with no help of lysergic substances. No wonder he faced a Sisyphean task trying to explain this to us, mere children.

And that brings us to the river metaphor. Everything in nature depends on underlying change. Thus, for Heraclitus, “as they step into the same rivers, other and still other waters flow upon them.” So each river is composed of ever-changing waters.

If you step into the Ganges or the Amazon one day, that would be something completely different compared with stepping in on another day.

Thus the notorious mantra Panta rhei, “Everything flows”. Flux and stability, unity and diversity, are like night and day.

One river may consist of many waters, and even if there are many waters, it’s still one river. That’s how Heraclitus reconciled conflict and unity into harmony – quite an Eastern philosophy concept.

No fragment tells it explicitly. But what’s fascinating is that flux in unity and unity in flux do look like moving parts of the logos, the guiding principle of the world, which no one before him had managed to understand.

Next to your fire

Everything flows. And that brings us to war – and once again Heraclitus meets Sun Tzu: “War is father of all and king of all.”

That also brings us to fire. The world is “fire ever living” and “fire for all things, as goods for gold and gold for goods.” Here Heraclitus seems to be equating gold, as a vehicle of economic exchange, to fire as a vehicle of physical change. He would have despised fiat money; Heraclitus was definitely in favor of the gold standard.

No wonder Heraclitus fascinated Nietzsche because he was essentially proposing a cyclical theory of the universe – Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence – with everything turning into fire in serial cosmic bust-ups.

Heraclitus was a Taoist and a Buddhist. If opposites are ultimately the same, this implies the unity of all things.

Heraclitus even foresaw the reaction we should have towards Covid-19: “It is disease that makes health sweet and good; hunger, satiety; weariness, rest.” Lao Tzu would approve. In the Heraclitus framework of serial cosmic recycling, disease gives health its full significance.

This collective attitude could go a long way to explain the relative success of Eastern societies in the fight against Covid-19 compared with the West.

And once again, all this Heraclitean interconnectivity could not be more Eastern – from Tao to Buddhism. No wonder the grandmasters of Western civilization, Plato and Aristotle, didn’t get it.

Plato distorted Heraclitus like there was no tomorrow. Plato based his analysis on Cratylus, a philosopher who misunderstood Heraclitus in the first place. Because Plato and Aristotle basically regurgitated Cratylus’s reductionist interpretation everyone afterward followed them, not the original Riddler.

For Plato and Aristotle, it was impossible to understand Heraclitus because they seemed to have taken “You cannot step into the same river twice” literally.

Heraclitus in fact discovered, for all humanity to see, that rivers and everything else in nature change constantly. They’re all about flux, even when they seem still. Call that a definition of history.

At least Plato’s misguided interpretation raised a key question we are still debating 2,500 years later: How is it possible to have certain knowledge of an ever-changing world? Or as Nietzsche famously put it: There are no facts, only interpretations.

So because of Plato’s misunderstanding, Heraclitus the genuine article became a sideshow in the history of thought. The Riddler would not have given a damn. It’s up to us to do him justice in these anguished times.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Asia Times.

Pepe Escobar is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from Wikimedia Commons