China’s Role in Amplifying Southern Africa’s Extreme Uneven Development

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg and Twitter at @crglobalization. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

First published on CADTM in June 2021.

Like so many regions of the world, the 14 ‘Southern African Development Community’ countries are grappling with the complex problem of Chinese state and corporate involvement in divergent societies, politics, economies and ecologies. There is enormous concern rising now about these relationships, in part because of a new chapter in the Cold War between Beijing and Washington, leaving Southern Africa torn, divided and subject to new forms of exploitation. After centuries of slavery, colonialism and imperialism, a degree of political independence was won between the 1960s-90s, with a terrible loss of life due to white supremicism. But since then, the region has still suffered from neo-colonialism, inter-imperial rivalries, sub-imperialism, neoliberalism, sustained patriarchy, resource-looting and now also the global climate meltdown and differential access to Covid-19 treatment and vaccines. China’s role is often an amplifier of these forms of oppression, but not always. It is vital to distinguish between functions that may assist the region in autonomous, sovereign self-development, on the one hand, and those that have negative implications for the region’s relationship to the world economy on the other. Social activists often provide guidelines to help make these distinctions, critiquing China for its amplification of the region’s extreme uneven development.

Introduction: Trends in Chinese-Southern African relations during economic crisis

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) region consists of Angola, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. What is the role of China in SADC, given not only massive recent investments, loans and trade relationships with these 14 countries, but also its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)? After all, BRI’s reach is exceptionally ambitious, reaching as far off the beaten track as Southern Africa. Still, as of 2021, several SADC countries have not yet joined BRI: Mauritius, Lesotho, Eswatini, Botswana, Malawi and the DRC. And Eswatini’s long-standing Taiwan relations remain a source of growing tension with Beijing.

The main Chinese investments and loans in South Africa require unpacking because they are within the BRI, conceptually, but due to systemic corruption and ecological destruction, social resistance has arisen to the main projects. The ones discussed below are port expansion in Durban (already Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest), rail expansion to export coal from Limpopo province, an auto factory in Nelson Mandela Bay, the largest coal-fired power plant under construction in the world (Kusile), and the largest Special Economic Zone in South Africa (Musina-Makhado).

These projects were all begun during the 2010s with most continuing into the 2020s. Not only are they logical corollaries to the corporate/parastatal ‘Minerals-Energy Complex’ which exerts so much influence on local capital accumulation. They can also be understood as a function of a plenary talk at the World Economic Forum in early 2017, just before Donald Trump took power, in which Xi Jinping (2017) clarified his ideology: “We must remain committed to developing global free trade and investment, promote trade and investment liberalisation.”

In a 2015 talk, Xi had insisted on the merits of trade among his emerging-economy partners in the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa BRICS bloc. These economies must “boost the centripetal (unifying) force of BRICS nations through cooperation in innovation and production capacity to boost competitiveness” (Xi 2015). However, in reality, the supposed ‘centripetal’ economic strategy – i.e., that as the world turns, it becomes more tightly integrated – was increasingly centrifugal, given tendencies to deglobalisation that were underway already by 2007, the peak of internationally-integrated trade, finance and investment.

Well before Covid-19 disrupted the world economy, part of the reason for this process was China’s own tendencies to capitalist crisis, resulting in a ‘going-out’ process to displace its massive industrial overcapacity, but in a context of slower rates of trade, investment and cross-border financial flows. Chinese exports and imports both rose rapidly on three occasions: 2003-08, 2009-15 and 2020-21. Two global crashes help explain the subsequent 2009 and 2020 upticks, but remarkable here is the slowdown from 2014-20. Notwithstanding the current spike, as a share of GDP, China’s trade is so far below 2007’s peak level, that it is the world’s main driver of deglobalization.

Moreover, the trade that was occurring just before Covid-19 hit was increasingly disconnected from what are known as ‘value chains’: globally-integrated production systems. McKinsey Global Institute’s 2019 ‘global flows’ analysis confirmed, “…a smaller share of the goods rolling off the world’s assembly lines is now traded across borders. Between 2007 and 2017, exports declined from 28.1 to 22.5 percent of gross output in goods-producing value chains” (McKinsey 2019). The decline in trade intensity in these chains was also led by China, where gross exports as a share of gross output in goods fell from 18 percent to 10 percent from 2007-17.

The centripetal strategy expressed by Xi in 2017 was not taking hold. Instead, a centrifugal process entails ever-greater outward stress on a system as it turns, pushing an object away from the centre, potentially leading to its disintegration. Ironically, even before Covid-19 briefly wrecked the global economy in the first half of 2020 beginning in China, the decline in world trade/GDP ratios was led not only by China but the rest of BRICS group; i.e., the economies that once were considered by Goldman Sachs manager Jim O’Neil (2001) to be what he called the ‘building BRICS’ of 21st-century capitalism.

South Africa was hit especially hard by the decline in Chinese commodity imports (coal, platinum group metals, gold and iron ore are the main four). South African trade fell from 73 percent of GDP in 2007 to 58 percent in 2017, compared to a world trade/GDP decline over that period from 61 percent of GDP to 56 percent. All the BRICS witnessed reduced trade in much greater degrees than the global norm, and three spent parts of 2015–19 in recession: Brazil, Russia and South Africa. In 2020, only one (China) recorded positive GDP growth.

One classical symptom of economic crisis that since the early 2010s has emanated mainly from Chinese companies, is what can be termed the overaccumulation of capital, reflecting systemic overcapacity. China has over-invested in its plant, equipment and machinery, so much, that the ability to continue to generate growth is limited. This overaccumulation of capital is recognised by left-wing and right-wing economists alike.

For radical critics, overaccumulation has various symptoms. Given the intercapitalist competition within and between industries which leads to ever rising capital intensity and hence overproduction, there is a tendency for gluts to develop: high inventory levels, unused plant and equipment, excess capacity in commodity markets, idle labour and bubbling financial capital. Because profits are higher in the banking sector and stock markets, corporations that had been accumulating within the productive economy find it more lucrative to shift from reinvestment in fixed capital, into purchasing ‘fictitious capital’ (financial, paper assets) (Bond 2019).

Among orthodox economists, staff at the International Monetary Fund (IMF 2017a) studied Chinese capital overaccumulation and found that in major sectors – coal, steel, nonferrous metals, cement, chemicals and others where Chinese demand is between 30-60 percent of the world market – there exists at least one third overcapacity in production. And due to overindebtedness, a financial crisis can break out at any time, causing domestic and global growth to fall and worsening the living conditions of hundreds of millions of Chinese people.

In a subsequent analysis of Chinese companies that are so far in debt that they are considered ‘zombies,’ the IMF (2017b) advocated “phasing out the implicit support and making better use of resources that are currently going to zombie firms, overcapacity industries, and state-owned enterprises.” And in an economic review published in late 2020, the IMF (2020, 9) remarked on how the state’s Covid-19 financial aid “contributed to a further increase in already very high corporate debt and exacerbated existing structural problems by prolonging the economic life of non-viable and low-productivity firms, including SOEs, particularly in capital-intensive sectors with overcapacity.”

This is not surprising, according to sociologist Ho-fung Hung (2015): “Capital accumulation in China follows the same logic and suffers from the same contradictions of capitalist development in other parts of the world . . . [including] a typical overaccumulation crisis.” Well before Covid-19 amplified the country’s economic stresses, these conditions were becoming acute. According to political economist Xia Zhang (2017, 321-22), they reflect Chinese capitalism’s “restructuring as the result of overaccumulation. Often jointly with various representatives of Chinese capital, the Chinese state is compelled to reconfigure Chinese capitalism on a much larger spatial dimension so as to sustain the capital accumulation and expansion.”

One recent IMF survey of economic sectors suffering low capacity utilization confirmed how overcapacity was correlated to Chinese firms’ overseas Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) during the critical period of ‘going out,’ as such overseas activity is termed, during the mid-2010s:

The IMF economists observed,

- China’s export-driven growth model until the mid-2010s gave companies incentives to constantly expand capacities in sectors where their comparative advantage led to ever greater international market shares, which in turn reinforced such comparative advantages. However, as growth began slowing down in China, capacity utilization started to decline, putting pressure on corporate profitability. With limited room for to grow domestically, Chinese companies had to seek new markets to relocate capital and keep the pace of expansion, the latter an important consideration for the SOEs as they were often tasked to support governments at all levels to meet the growth targets. Indeed, there seems to be a negative correlation between China’s overall capacity utilization index and the level of its overseas investment. (Ding et al 2021, 19)

Progressive activists understand this too. As articulated by the 2017 Hong Kong People’s Forum on BRICS and the BRI,

- Instead of offering an alternative, the BRICS actually offer a continuation of neoliberalism. On top of BRICS there is also China’s new mega project, the BRI whose main purpose is to export China’s surplus capital, and in this process seek the cooperation and ‘mutual benefit’ of big foreign TNCs and regimes which are often authoritarian. The price of these investments is often borne by the working people and the ecological balance. (Borderless Hong Kong 2017)

From overaccumulation to a ‘New Scramble’ and resurgent geopolitical tensions

The economic crisis conditions are also playing out in a manner they have in past confrontations, in the late-19th century era of imperialism that led to World War I. Geopolitical influences are today being acutely felt, in the tug of war between West and East. There is enormous concern about whether Sino-African relationships will become the source of Western-African conficts, in part because of the way U.S. President Joe Biden is maintaining the intensity of the new Cold War between Beijing and Washington begun by his predecessor Barack Obama (2009-17) and continuing under Donald Trump (2017-21), leaving SADC countries torn, divided and subject to new forms of exploitation.

Under Trump, there was practically no effort to woo African countries – which he infamously termed s*&!-holes – to the U.S. side. But this will change under the Biden Administration, as the G7 meeting in June 2021 confirmed the West’s desire to establish a global ‘Build Back Better World’ alternative plan to the dirty BRI infrastructure. As Biden put it, the strategy “will collectively catalyze hundreds of billions of dollars of infrastructure investment for low- and middle-income countries in the coming years” through “a values-driven, high-standard, and transparent infrastructure partnership led by major democracies to help narrow the $40+ trillion infrastructure need in the developing world.”

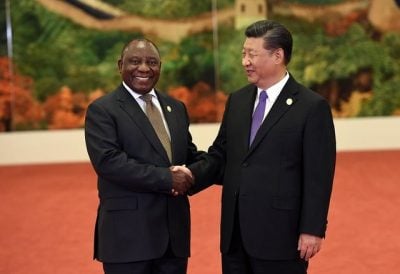

These ‘democracies’ – the U.S., Japan, Germany, United Kingdom, France, Italy and Canada – include the three main colonial and neo-colonial powers whose infrastructure investments since the 19th century invariably aimed to link ports – via railroads, roads and bridges – to mines and plantations, so as to better extract minerals and cash crops. Their Cornwall meeting in June 2021 did include as guests the two most important pro-Western leaders from Asia (India’s Narendra Modi) and Africa (South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa). But their attempts to achieve their main stated objective – i.e., to solve the Covid-19 catastrophe by gaining universal access to generic vaccines and treatments – were rebuffed.

The G7 includes one country – the U.S. – whose leader bowed to popular pressure by accepting (in principle) the idea that Covid-19 vaccines could be removed from World Trade Organization Intellectual Property restrictions during the continuing pandemic. While G7 leaders had over-ordered vaccines for their citizenry (in Canada’s case by a factor of five), the Indian and South African peoples were suffering higher rates of infection and more rapidly-buckling health systems than anywhere else on earth. That made no apparent difference at the G7 summit.

The original ‘Scramble for Africa’ – when the continent’s borders were carved – occurred in 1884-85 in a Berlin conference room, and divided peoples as a result of the whims of representatives from Britain, Portugal, France, Belgium and the host Germany. In the SADC region, each colonial power land-grabbed and to differing extents, each established settler-colonial white power over the inhabitants and nature. This Scramble represented not just colonial powers taking territories, but capitalism expanding voraciously during its own economic crisis.

According to Rosa Luxemburg, the German Communist leader who read about Namibia, the DRC and South Africa and then wrote The Accumulation of Capital in 1913,

- Capitalism must therefore always and everywhere fight a battle of annihilation against every historical form of natural economy that it encounters… The most important of these productive forces is of course the land, its hidden mineral treasure, and its meadows, woods and water, and further the flocks of the primitive shepherd tribes. Since the primitive associations of the natives are the strongest protection for their social organisations and for their material bases of existence, capital must begin by planning for the systematic destruction and annihilation of all the non-capitalist social units which obstruct its development.

Is there a new Scramble for Africa now underway, as some describe the way not only the Western colonial powers, but also South Africa and China, behave in the region? As far as the BRI is concerned, it is undeniable that two serious problems with China’s strategy are emerging. First, tension with India is acute, due to BRI’s Kashmir link via Pakistan, close to the area where Delhi is repressing a political uprising and where Sino-Indian conflict in mid-2020 led to dozens of troops’ deaths, on both sides. The second, discussed below, is rising resistance to social, environmental, political and economic injustice, which though mainly directed against tyrannical governments (some supported by the West, some by China), also have roots in structural features of the China-Africa relationship, especially resource extraction.

Membership in the BRI is now taken for granted for those in proximity, with the exception of India, where the link from Pakistan’s Gwadar port to the western edge of China could make import of Middle East petroleum and other vital supplies much easier, and far less risky than the ocean route (what with its bottlenecks and geopolitical tensions). But India’s own agenda creates a competitive conflict that has not yet been resolved, in part because India began its own counter-BRI strategy, the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor, in alliance with Japan in 2017.

Meanwhile, the West complains that as the BRI allows for China’s expansion, Beijing still does not play by ‘fair’ rules. Whether Obama, Trump or Biden, Washington attacks China’s currency (considered to be artificially low so as to make exports more competitive), Intellectual Property theft, generous subsidies to parastatal corporations and protected domestic markets. In turn, this leads to the thorny question of whether a new Cold War has begun, in which Africa will be a pawn, yet again.

While the Biden Administration will reverse some of the more irrational U.S.-China trade war provisions imposed by Trump, there are others in the realm of state security and Big Tech that will be continued. Some of Wall Street’s largest firms are extremely exposed in China through direct investment, supplier relations, Research & Development contracts (which earn the corporates massive royalties), and consumer markets. And Beijing still owns more than $1.1 trillion in Treasury Bills, although that holding has not increased since 2012.

In spite of these interconnections, geopolitical tensions in the South China Sea began rising in 2011 with Obama’s imperialist ‘pivot to Asia.’ This meant, wrote journalist John Pilger (2016),

- almost two-thirds of US naval forces would be transferred to Asia and the Pacific by 2020. Today, more than 400 U.S. military bases encircle China with missiles, bombers, warships and, above all, nuclear weapons. From Australia north through the Pacific to Japan, Korea and across Eurasia to Afghanistan and India, the bases form, says one US strategist, ‘the perfect noose’.

In addition, Eurasia is a testing ground because of increasing investments in Chinese infrastructure via the BRI. These are being funded in part by the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), centering on Russian-Chinese energy cooperation, and moving quickly without Washington’s membership thanks originally to Obama’s (impotent, incompetent) opposition. The situation became yet more dangerous due to Trump’s mercurial character, ruthless pragmatism, exceptionally thin skin, crude bullying behaviour and ability to polarise his own society and the world.

Even though in early 2021, Trump was replaced by a much smoother U.S. leader, Biden, further belligerence can be anticipated, including aspects of the trade war that relate to U.S. military interests, where Biden will more reliably represent the Military-Industrial Complex than did the erratic Trump.

In contrast to Trump, Obama pursued a dual strategy not only of enhancing the military theat to Beijing, but also of assimilating China into Western-dominated multilateralism, including much bigger roles (and higher voting shares) in the traditionally exploitative Bretton Woods Institutions. In 2014, Obama agreed with The Economist (2014) magazine’s editor, who interviewed him about “the key issue, whether China ends up inside that [multilateral financial] system or challenging it. That’s the really big issue of our times, I think.” Obama replied, “It is. And I think it’s important for the United States and Europe to continue to welcome China as a full partner in these international norms.”

In contrast to this rhetoric, Obama in 2015 dogmatically (and unsuccessfully) discouraged AIIB membership by fellow Western powers and the Bretton Woods Institutions. It was his most humiliating international defeat. But when it came to intensified trade liberalisation in the WTO, recapitalisation of the IMF under neoliberal rule, and destruction of the binding emissions reductions targets on Western powers that characterised the Kyoto Protocol, Obama’s strategy of bringing China and the other BRICS leaders inside was much more successful.

For such reasons, the role of these countries can be considered ‘subimperialist,’ in the original sense of the term, as defined by the Brazilian dependency theorist Ruy Mauro Marini (1972): “collaborating actively with imperialist expansion, assuming in this expansion the position of a key nation.”

This collaboration was expressed the day before Trump took office in early 2017, when instead of the New York real estate tycoon, it was Xi Jinping who went to the Davos World Economic Forum to commit to expanding global capitalism. In contrast to Trump’s protectionism and ‘America First’ rhetoric, Xi’s plenary talk clarified his ideology:

- There was a time when China also had doubts about economic globalisation, and was not sure whether it should join the WTO. But we came to the conclusion that integration into the global economy is a historical trend… Any attempt to cut off the flow of capital, technologies, products, industries and people between economies, and channel the waters in the ocean back into isolated lakes and creeks is simply not possible… We must remain committed to developing global free trade and investment, promote trade and investment liberalisation… We will expand market access for foreign investors, build high-standard pilot free trade zones, strengthen protection of property rights, and level the playing field… China will keep its door wide open and not close it. (Xi 2017)

Actually, not only did Xi effectively respond in kind to Trump’s tariffs by imposing countervailing tariffs, he also engineered a decline in the Chinese currency to below RMB7/$ in August 2019. And well before Trump, Xi proved his rhetoric of liberalisation was not matched by reality, for during six months starting in mid-2015, Beijing imposed stringent exchange controls, stock market circuit breakers and financial regulations to prevent two Chinese stock market collapses from spreading beyond the existing $5 trillion in losses. Moreover, within eighteen months of his Davos speech, Xi had authorized a set of trade restrictions on US products in retaliation for Trump’s protectionist tariffs. Channeling toxic waters of excessively chaotic capitalist globalisation back into economic purification systems is indeed possible, and necessary.

The deglobalisation process illustrates the trend. As noted above, the trade/GDP ratio and share of output from global value chains were falling prior to Covid-10. So even as China continued to play the role of global leader in capital accumulation, becoming the largest economy in Purchasing Power Parity terms, the country’s GDP was estimated to rise at only around 6 percent in 2019, the lowest rate in 25 years, and 2020 growth was far lower due to Covid-19. Prior to the unsustainable late-2020 revival, the import shrinkage adversely affected African countries which had long become dependent upon Chinese purchasers of their commodities.

As a result, China’s internal economic contradictions are becoming more acute, in part because the national debt doubled from 150 percent of GDP in 2007 to more than 300 percent by 2018. In addition, the Chinese “elite who control the state sector seek capital flight, encroach on the private sector and foreign companies, and intensify their fights with one another,” explains Hung (2018, 162):

- The post-2008 boom was driven by reckless investment expansion funded by a state-bank financial stimulus. This created a gigantic debt bubble no longer matched by commensurate expansion of the foreign-exchange reserve… The many redundant construction projects and infrastructure resulting from the debt-fueled economic rebound are not going to be profitable, at least not any time soon. The repayment and servicing of the debt is going to be challenging, and a major ticking time bomb of debt has formed. This overaccumulation crisis in the Chinese economy is the origin of the stock market meltdown and beginning of capital flight that drove the sharp devaluation of Chinese currency in 2015–16.

From late 2015, the Chinese imposed tighter exchange controls not only to prevent financial capital flight but also to confront overaccumulation with so-called Supply-Side Structural Reforms, so as to “guide the economy to a new normal.” Beijing had five strategies, namely, capacity reduction, housing inventory destocking, corporate deleveraging, reduction of corporate costs, and industrial upgrading with new infrastructure investment. The “three cuts, one reduction, and one improvement” was, according to a favourable World Bank staff review in 2018, “a departure from China’s traditional demand-side stimulus policies” (Chen and Lin, 2018).

The dilemma in coming years is whether the other contradictions in the Chinese economy, especially rising debt and the on-and-off trade war with the United States (potentially spilling into other economies trying to resist devaluation), will turn a managed process into the kind of capitalist anarchy that causes overaccumulation in the first place. If so, it will be ever more important to coordinate worker and community resistance to the devaluation process with international solidarity. What are currently tit-for-tat protectionist responses (often accompanied by right-wing xenophobic politics) must be transformed into a genuine globalisation of people, with the common objective of degrowth for the sake of socio-ecological sanity.

Civil, political, socio-economic and environmental factors

China has had a strong state for centuries, in spite of the era from 1839 to 1949 when first the British and French and then Japanese imperial powers invaded and occupied crucial parts of the country. In the past three decades, since the Tiananmen Square repression of 1989, many more human rights concerns – and social protests – have been expressed, with growing concern that Xi’s regime has taken its powers to extreme levels. Since the late 1970s, Beijing’s imposition of liberalising capitalist development – without democratisation – has entailed heightened authoritarianism, unprecedented levels of surveillance, repression of minorities especially in the Western provinces, rural land grabs in the context of an apartheid-like migrant labour system, selective prosecution of corruption, and the demise of the Iron Rice Bowl state welfare system.

Before the revolution led by Mao Tse Tung in 1949, rural China was fragmented, inefficient and repressive. His centralisation of agricultural production attempted to transform the peasantry, but led to mass starvation in 1959-61. Heavy industrial investment and strict planning allowed cities to capture surpluses, while the gap in society’s basic needs was met through an “iron rice bowl” welfare model that included state-company housing as well as schools and hospitals. Literacy improved from 20 to 83 percent of the population from 1952-78. The core system of labour control is ‘hukou’, whose parallels with apartheid’s migration constraints are notable. After liberalisation began, three hundred million rural workers moved to cities on a temporary registration basis. According to Kevin Lin (2015, 71),

- The first generation [of migrant workers] were rural peasants who, pushed by rural poverty and pulled by the burgeoning urban economy, migrated to China’s urban centres in the 1980s. Their city wages were meagre but still higher than their rural incomes. For young women, factory work and urban life also brought a new sense of freedom. But the household registration system and their own rural roots meant that the first-generation migrant workers have been predisposed to eventually returning to their villages.

- It is the family farm that lends the migrant worker away from home a substitute for the benefits he or she is not getting from urban work, as well as security in the event of dis-employment or unemployment or in old age, while this same worker helps supplement the otherwise unsustainably low incomes of the auxiliary family members engaged in underemployed farming of small plots for low returns. So long as substantial surplus labour remains in the countryside, the key structural conditions for this new half-worker half-cultivator family economic unit will prevail.

During an era in which millions of former Township and Village Enterprises have closed and there is no longer an Iron Rice Bowl, the ability of Beijing to maintain super-exploitative wages for the benefit of transnational corporate investors is partly based on the gendered dimension. As Julia Chuang (2016, 484) explains of rural gender relations,

- In the sending community, women face a double bind: they are expected to support husbands who engage in precarious and high-risk migrations; and they are expected to negotiate with those husbands to channel a portion of remittance income to their aging parents, who lack access to welfare or social support.

The tasks are harder given how few resources Beijing allocates from its massive surpluses to social welfare. Among the world’s 40 wealthiest economies measured by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2019), the Chinese share of social spending to GDP – like South Africa’s – is just 8 percent, far short of the OECD average of 22 percent. Only India, Indonesia and Mexico are lower in this peer group.

One result is rising social discontent. The last year that the Chinese government released statistics on protests was 2005, when there were 87,000. In recent years, according to Bin Sun (2019, 429), “More than 600 mass protests a day erupt in China, more than 200,000 a year. Of these, over 100,000 occur in rural areas, of which perhaps 65 percent are linked to residents’ loss of land… Chinese governments will repress religiously rooted resistance, tolerate economically motivated actions, and encourage nationalistically inspired demonstrations.”

Sometimes the protests are a good pressure-cooker indicator, leading to adjustments in state practices, including removal of officials seen to be hostile to communities or workers. In his book Responsive Authoritarianism in China: Land, Protest, and Policy Making, Christopher Heurlin (2016, 3) shows how Beijing “proactively monitors citizen opposition to state policies and selectively responds with policy changes when it gauges opposition to be particularly widespread.”

However, the exceptional advances in Beijing’s Social Credit surveillance system are now capable of not only predicting the location and timing of protests – through systematic monitoring of grievances expressed on China’s Facebook equivalent, Weibo – but also punishing activists. Although the U.S. agency Freedom House is not always reliable, what it terms the China Model of Internet Control is undeniable, and entails the Great Firewall, content removal, revoking access by users, manipulation of social media and high-tech surveillance, as well as violence, arrests and repression. One example, internet journalist Lu Yuyu, was a prolific analyst of labour and social protests. He and his partner Li Dingyu were arrested in 2016 on charges of “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble.” After jail beatings, Lu was sentenced in 2017 to four years in prison (Committee to Protect Journalists 2017).

Social Credit scoring was announced in 2014 as a way to “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.” By late 2018, Beijing’s National Public Credit Information Centre revealed, Chinese courts banned would-be travellers from buying flights on 17.5 million occasions, and from buying train tickets 5.5 million times. The system’s roll out is scheduled for 2020. This is part of a general arsenal aimed at assuring totalitarian social control. As Wired magazine reported in 2019,

- The Chinese government is already using new technologies to control its citizens in frightening ways. The internet is highly censored, and each person’s cell phone number and online activity is assigned a unique ID number tied to their real name. Facial-recognition technology is also increasingly widespread in China, with few restraints on how it can be used to track and surveil citizens. The most troubling abuses are being carried out in the western province of Xinjiang, where human rights groups and journalists say the Chinese government is detaining and surveilling millions of people from the minority Muslim Uyghur population on a nearly unprecedented scale. (Matsakis 2019)

Occupation and resident re-education camps are common especially in Xinjiang and Tibet, where minority ethnic nations have long demanded greater rights and self-rule. In November 2019, The New York Times (2019) published 403 pages of proof – the ‘Xinjiang Papers’ – from within the Chinese state, showing how after a train station attack by Islamic extremists in 2014, Xi ramped up the repression. He called for a ‘struggle against terrorism, infiltration, and separatism’ using the ‘organs of dictatorship,’ and showing ‘absolutely no mercy’ against those with ‘strong religious views,’ a process which began in earnest in 2017. Beijing’s répression of Hong Kong democracy protesters is playing out in the extraordinary activism now in process. The demonstrations are being watched closely by SADC activists since so many of the creative tactics being used to escape surveillance will be vital in a region whose authoritarian and democratic leaders have often stooped to illegal spying on the citizenry.

To illustrate, the confluence of Chinese elite interests and South African leaders was on display three times – in 2009, 2011 and 2014 – when the South African government denied or delayed a travel visa for the Dalai Lama, respectively for a peace conference, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu’s 80th birthday and a Nobel Peace Prize laureates’ workshop. On the final occasion, Beijing’s Foreign Ministry spokesman celebrated “the respect given by the South African government on China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and the support given to China on this issue” (Reuters 2014). In 2015, the Foreign Ministry’s lead Africa official, Lin Songtian, complained that while Beijing was helping Jacob Zuma develop ten Special Economic Zones, the Dalai Lama “can’t just come and spoil this for you and we want a friendly atmosphere and environment for this to happen. We invest a lot of money in South Africa and we can’t allow him to come and spoil the good relations” (Mazibuko 2015).

The sovereignty of the South African state was also violated in late 2015, in the reversal of the appointment of finance minister Desmond van Rooyen, who was widely seen as a dangerously ill-equipped crony of Zuma. According to Business Day publisher Peter Bruce (2016): “I have reliably learnt that the Chinese were quick to make their displeasure known to Zuma. For one, their investment in Standard Bank took a big hit. Second, they’ve invested way too much political effort in South Africa to have an amateur mess it up. Their intervention was critical.” (Bruce saw this as a highly favourable development.)

In the other case of a widely-applauded Chinese intervention in the affairs of an African state, the November 2017 coup against Robert Mugabe followed major investments and then a fall-out. China had been invited to Zimbabwe for weapons sales and stakes in tobacco, infrastructure and mining, and its retail imports continue to deindustrialize Zimbabwean manufacturing. Mugabe’s successor Emmerson Mnangagwa had fought Rhodesian colonialism in the 1970s, and was one of Mugabe’s leading henchmen, rising to the vice presidency in 2014. But Mugabe fired him on November 6, signaling his wife Grace’s ruthless ascent. Mnangagwa’s fate was the catalyst for an emergency Beijing trip by his ally, army leader Constantino Chiwenga, for consultations with the Chinese army command. Mnangagwa received military training in China during Mao’s days (CNN 2017).

Beijing’s Global Times, which is often a source of official wisdom, was increasingly wary of Mugabe. According to a contributor, Wang Hongwi (2017) of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences,

- Mnangagwa, a reformist, will abolish Mugabe’s faulty investment policy. In a country with a bankrupt economy, whoever takes office needs to launch economic reforms and open up to foreign investment… Chinese investment in Zimbabwe has also fallen victim to Mugabe’s policy and some projects were forced to close down or move to other countries in recent years, bringing huge losses.

Amongst the populace, Mnangagwa remains widely mistrusted due to his responsibility for (and refusal to acknowledge) 1982-85 ‘Gukhurahundi’ massacres of more than 20,000 people in the country’s western provinces (mostly members of the minority Ndebele ethnic group, whose handful of armed dissidents he termed “cockroaches” needing a dose of military ‘DDT’); his subversion of the 2008 presidential election which Mugabe initially lost; his subsequent heading of the Joint Operations Committee secretly running the country, sabotaging democratic initiatives; as well as for his close proximity – as then Defence Minister – to widespread diamond looting from 2008-16 (Bond 2017a).

In 2016, Mugabe himself complained of revenue shortfalls from diamond mining in eastern Zimbabwe’s Marange fields: “I don’t think we’ve exceeded US$2 billion or so, and yet we think that well over US$15 billion or more has been earned in that area.” In order for Mnangagwa to establish the main Marange joint venture – Sino Zimbabwe – with the notorious (and now apparently jailed) Chinese investor, Sam Pa, the army under Mnangagwa’s rule forcibly occupied the Marange fields. In November 2008, troops murdered several hundred small-scale artisanal miners there (Bond 2017a).

There have been many other instances of Chinese investors propping up African dictators, but in the SADC region, the case of Sam Pa’s relationship with Jose Eduardo Dos Santos stands out. According to respected commentator António Pereira, “Pa exploited this relationship to secure total control over construction projects in Angola. The construction of the new airport [Aeroporto Internacional de Angola] is a continuation of Pa’s, CIF’s and by extension, China’s monopoly on Angola construction projects” (Africa News 2018). He also worked with Beijing parastatal Sinopec to acquire Angolan oil fields. Pa was arrested in China in 2015 after apparently falling foul of anti-corruption prosecutions that took down high-ranking party and state officials. His current whereabouts are unknown.

These are examples of local socio-economic, civil and political, and environmental violations. The most dangerous, however, are in the ways China, South Africa and other high-emitting countries continue to create climate-crisis conditions in the SADC region. Weak regulation of HCFCs, toxins and plastic products are becoming a major problem, although China’s lead in solar and wind energy generation and decision to ban waste imports are positive signs.

The combination of socio-economic and environmental damage is also evident in mega-projects, which we take up next in a brief review of the five main cases of Chinese investments and loans in South Africa.

China’s controversial role in South African mega-projects

The five largest projects involving South Africa are illustrative of the problems described above, especially those that conjoin political corruption, maldistributed economic benefits, social dislocation and ecological damage. The two biggest current projects in South Africa entail export of coal on a new rail line, and expansion of Durban’s port – the ‘Presidential Infrastructure Coordinating Commission Strategic Integrated Projects’ 1 and 2.

Campaigns for reparations have been launched against Chinese vendors, especially in Transnet’s acquisition of rail equipment. They began to succeed in early 2018, due to blatant corruption in the state transport agency’s purchase of several hundred locomotives designated to export 18 billion tons of coal in what was then a $50 billion bulk rail upgrade project.

The Chinese connection also entailed a commitment by the China Development Bank in 2013 to provide $5 billion in credit to Transnet for its capital investments, a sum that would in part pay for China South Rail’s provision of locomotives. The purchase price also included $2.9 billion in ‘irregular expenditures’ apparently known to the firm’s CEO Zhou Qinghe ; these were corruption payments to the Gupta brothers via a Transnet official. Those brothers had notoriously ‘state captured’ the South African president at the time, Zuma, through his son Duduzane whom they had employed. As a result of the public outcry, Zuma was pushed out of power in early 2018, nearly a year and a half before his term ended (Bond 2020).

The second biggest mega-project in South Africa is the expansion of what is already the largest sub-Saharan African container terminal, costing $15 billion. In the first stage, a much smaller case of Gupta bribery occurred, again via Transnet, during the purchase of seven tandem-lift ship-to-shore cranes used mainly to import goods from East Asia. These were provided by Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries (in partnership with Liebherr-International of Switzerland) and entailed an $8 million payoff to the Guptas as part of what were termed the ‘world’s most expensive cranes’ due to the markup and supplier profiteering (Amabhungane 2017).

The most important point about the Durban port expansion, however, is that it is firmly opposed – and regularly protested – by the main social movement in the area, the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance due to the large-scale pollution and displacement (Bond 2017b).

Third, another major port city further down the Indian Ocean coast is the Nelson Mandela Bay municipality (formerly Port Elizabeth). It includes a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) with substantial tax benefits at the area known as Coega, and contains the largest single Chinese manufacturing investment in South Africa. The Beijing Automobile Industrial Corporation (BAIC) plant is co-financed by the South African state’s Industrial Development Corporation (IDC).

In mid-2018, the first semi-knock down Sport Utility Vehicle came off the BAIC assembly line, just a day before the BRICS Summit was to start in Sandton. The manufacturing plant cost nearly $1 billion (then R11 billion), and was the single largest Foreign Direct Investment in any of the main South African SEZs. In June 2018, Chinese Ambassador to South Africa Lin Songtian stated, “I’ve been to many developing countries and industrial development zones and the Coega SEZ is by far the best of them all” (Toussaint et al 2019).

However, in the subsequent year, the BAIC/IDC joint venture encountered many difficulties. The University of the Western Cape (Toussaint et al 2019) report on SEZs documented these:

- Crises included inadequate Small, Medium and Micro Enterprise involvement, budget shortfalls for the start-up phase, differential labour laws, and delays in production, which played havoc with the image projected of a functional SOE partnership. As one report in the (partially Chinese-owned) Independentnewspaper chain confessed in 2019, “Serious doubts have been expressed in motor industry circles about the claims that the vehicle was manufactured in South Africa… Last September, the local media reported that the construction had been moving at a snail’s pace and all SMMEs had vacated the premises due to non-payment.”

Again, according to University of Western Cape analysts, one manifestation was local dissent:

- Local journalist Max Matavire reported on extensive labour and small business protests against BAIC during construction, and titled a November 2019 article, “Overambitious production targets delay R11bn BAIC project,” since BAIC “has missed its deadline by two years because it failed to meet its own overambitious and unrealistic production targets set at the launch… Currently, they are producing 50 000 vehicles per year from the semi-knocked-down kits. This will increase to 100 000 a year when fully operational”… Inadequate pay at the factory was the source of further grievances, according to media reports. Workers demanded twice the R24/hour that they were earning in 2018, and were on strike for several weeks, for the second time. (Toussaint et al, 2019)

Finally, at what is potentially the biggest SEZ in South Africa – at the far northern tip of the country – there is a $10 billion China-funded metals-manufacturing facility planned in a corridor termed Musina-Mukhado. One smaller part of the SEZ is just 50 km from the Zimbabwean border post of Beit Bridge. But it is the rural Makhado section that Chinese entrepreneur Ning Yat Hoi and his Shenzhen Hoi Mor Resources Holding Company chose for an 8000 hectare project, bordering the main highway heading north. That part of the Musina-Makhado SEZ (MMSEZ) is the energy-metallurgical complex (hence sometimes termed EMSEZ).

President Cyril Ramaphosa had co-chaired the Forum on China-Africa China Cooperation in September 2018, and in addition to promoting the MMSEZ, he announced a further $1.1 billion (R16.5 billion) loan from the Bank of China for SEZs and industrial parks in South Africa (Mokone 2018). If approved, the MMSEZ will contain a coal washing plant (with the capacity to process 12 million tonnes per year); a coking plant (3 million tonnes); an iron plant (3 million tonnes); a stainless steel plant (3 million tonnes); a ferro manganese powder plant (1 million tonnes); a ferrochrome plant (3 million tonnes); a limestone plant (3 million tonnes); and most controversially, a 3300 MW coal-fired power plant.

The latter is not incorporated in South Africa’s official Nationally Determined Contributions to cutting emissions mandated in the Paris Climate Agreement, nor in the Energy Department’s Integrated Resource Plan for added capacity. Water to cool the plant is not immediately available, and will require an international transfer from deep aquifiers in water-starved western Zimbabwe and Botswana.

Even the company hired by the MMSEZ to conduct environmental analysis, Delta BEC (2020), admitted that in terms of greenhouse gases, “emission over the lifetime of the project will consume as much as 10 percent of the country’s carbon budget. The impact on the emission inventory of the country is therefore HIGH. The project cannot be implemented in the current regulatory confines.” Delta BEC suggested the environmental contradiction could be overcome with a carbon-capture-storage strategy for the vast CO2 emissions, although no such proven technology exists.

Pressures arose against Delta BEC in early 2021 as community consultations failed to win buy-in, so the main staffer quit in disgust. The provincial agency in charge of the project worked with Ning to scale down the project, displacing several components from Makhado and reducing the power plant to 1320MW. Still, environmental legal critiques, (white) conservationist opposition, and (black) community resistance facilitated by Earthlife South Africa remained intense.

Moreover, corruption is another concern in a part of South Africa, Limpopo Province, that has notorious legacies of state capture. Ning had spent much of 2017-18 defending himself in court and was even on the Interpol ‘Red List’ for theft. In 2015-17 he served as board chair of a mining company in Zimbabwe, ASA Resource Group, but was fired by the other directors and charged with $5 million in alleged graft. At a November 2018 London High Court hearing on the case, the judge ruled that there were credible allegations against Ning for “stealing money, a corrupt relationship between Mr Ning and the Chinese suppliers and an alleged tortious conspiracy between the Chinese directors. The pleadings are extensive.”

Investigative journalists at Amabhungane (South Africa’s leading reporters) identified many suspicious relations between Ning and South African officials. These included dereliction of duty by the South African Ministers of Trade and Industry responsible for giving Ning permission to operate that part of the MMSEZ, Rob Davies and Ebrahim Patel (Amabhungane 2020).

Still, the project would continue because, according to one reporter,

- the concept of the MMSEZ was premised on extensive cross-border research to determine what commodities were crossing the Beit Bridge border with the top ten identified as being potential low-hanging fruit. The idea was that that instead of machinery and equipment being built in, say, Durban and shipped to a SADC country, it could far more advantageously be done in the MMSEZ (Ryan 2019).

In other words, the net benefit for South Africa was dubious, if the MMSEZ’s opening of new capacity in one part of the country simply shut down that capacity in another part, one where the tax rate was about twice as high. Indeed, the standard corporate tax rate for South African businesses was, in 1992 at the close of apartheid, 52 percent. It was reduced to 28 percent over the subsequent three decades and 27 percent in 2021. But still this was not sufficient to entice new investment by either local or foreign capital. The SEZ strategy is to lower the rate still further, to just 15 percent – the lowest corporate tax agreed by the G7 in 2021, to promote internationally.

In spite of the dilemmas associated with access to capital and to water, climate, and corruption, even the 2019 UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) special SEZ report unequivocally promoted the MMSEZ:

- In Africa, intercontinental trade and economic cooperation through border SEZs is also high on the agenda. The MMSEZ of South Africa is strategically located along a principal north-south route into the Southern African Development Community and close to the border between South Africa and Zimbabwe. It has been developed as part of greater regional plans to unlock investment and economic growth, and to encourage the development of skills and employment in the region (UNCTAD 2019: 160).

UNCTAD officials weren’t paying attention. There was a new truck route away from both Makhado and Musina, crossing Botswana in a northwesterly direction, avoiding the costly, inefficient northeasterly Zimbabwe border (Beitbridge) a few kilometers north of Musina. According to Africa trade analyst Diana Games:

- In May 2021, the Kazungula Bridge across the Zambezi River linking Botswana and Zambia was opened by the presidents of the two countries. The construction of the bridge, which replaces the longstanding, slow ferry service across the river, means trucks on regional routes can now cross the river in a few hours, or less, rather than the previous three days to a week. It also means they can avoid using the biggest crossing between the ports and factories of South Africa and the rest of southern Africa, Beitbridge, which is also one of the most congested borders in Africa. A one-stop border post at the bridge will allow easier thoroughfare.

The diversion of traffic from this essential ‘Gateway to Africa’ truck route is a formidable deterrent to the MMSEZ’s overall rationale. In working through Ning’s firm, and emphasizing much closer ties to the Zimbabwean and South African governments – while suffering often frosty relations with Zambia – the Chinese economic diplomats and others in FOCAC who entertained such high hopes for the MMSEZ witnessed a string of profound disappointments.

Conclusion: Potentials for reviving positive Chinese-SADC relations

The adverse conditions Chine capital accumulation is encountering in the South African cases discussed above, and indeed across the region, are indisputable, and will continue to be contested. Yet many Southern Africans know a different face of China, not only that of the super-exploitative state and private firms now active in the region.

Many ask whether Chinese workers, peasants and progressives could one day, just as they did in 1949, wrest their society away from a self-destructive ruling class now controlling the economy and state? To be sure, China’s role in Africa has often been honorable, and there are many reasons to admire and offer return solidarity to those forces which have consistently sought liberatory allies in Africa.

Chinese socio-ecological-economic advances celebrated by progressives everywhere include:

- China’s 1949 peasant-worker revolution and decolonisation – and later in the 1960s-70s, its crucial support for African anti-colonial struggles (especially Zimbabwe’s) and regional development aid (especially the Tanzania-Zambia railway);

- China’s capacity for rapid pollution abatement and renewable energy dissemination (based partly on disregard for the West’s Intellectual Property);

- China’s strength in maintaining international financial sovereignty through exchange controls and financial regulations (especially those imposed in 2015-16 to halt spreading stock market crashes into other markets);

- China’s 2009-14 expansion of mass housing, services, recreational and transport innovations (especially the “Chongqing Model” of municipal development promoted by China’s neo-Maoist ‘New Left’);

- China’s ongoing worker and peasant protests which are reputed to number more than 100 000 annually, in spite of often severe punishment;

- Chinese internet users’ ability to avoid Beijing’s repressive surveillance systems (including ongoing democratic organising in Hong Kong).

There are also Zhou Enlai’s ‘Eight Principles’ for Chinese interrelations with Africa dating back more than 55 years. As the first Premier of China, Zhou listed principles for foreign aid during a trip to Africa in late 1963 and early 1964:

- mutual benefit

- no conditions attached

- the no-interest or low-interest loans would not create a debt burden for the recipient country

- to help the recipient nation develop its economy

- not to create its dependence on China

- to help the recipient country with projects that need less capital and quick returns

- the aid in kind must be of high quality at the world market price to ensure that the technology can be learned and mastered by the locals

- the Chinese experts and technicians working for the aid recipient country are treated equally with local ones, with no extra benefits to them (Shixue 2011).

While many such principles, innovations and aspirations are admired by SADC progressives, the pages above considered the more recent, generally négative aspects of China’s socio-economic and environmental advances. These include Chinese parastatal and corporate investments, financing and trade, as well as in China’s role in multilateralism and its geopolitical power in Africa. The conclusion, hence, is pessimistic regarding the relationship binding Chinese and SADC elites. Yet there are grounds for optimism regarding social resistances that in future may reconnect Southern African progressives with their Chinese counterparts.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @globalresearch_crg and Twitter at @crglobalization. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Patrick Bond, Professor, University of the Western Cape School of Government. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Sources

Africa News. 2018. Disgraced Chinese tycoon building Angola’s new airport. 4 October, https://www.africanews.com/2018/10/04/disgraced-chinese-tycoon-building-angolas-new-airport//

Amabhungane. 2017. #GuptaLeaks: More multinationals ensnared in Transnet kickback web. 17 July. https://amabhungane.org/stories/guptaleaks-more-multinationals-ensnared-in-transnet-kickback-web/

Amabhungane. 2020. #EarthCrimes: Limpopo’s dirty great white elephant. 7 April. https://amabhungane.org/stories/earthcrimes-limpopos-dirty-great-white-elephant/

Bin Sun. 2019. Outcomes of Chinese Rural Protest. Asian Survey 59 (3): 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2019.59.3.429

Bond, P. 2017a. Zimbabwe witnessing an elite transition as economic meltdown looms. Pambauzka, 23 November. https://www.pambazuka.org/democracy-governance/zimbabwe-witnessing-elite-transition-economic-meltdown-looms

Bond, P. 2017b. Red-green alliance-building against Durban’s port-petrochemical complex expansion. In : Grassroots Environmental Governance: Community Engagements with Industry, L.Horowitz and M.Watts (Eds), London, Routledge, pp.161-185, http://www.tandfebooks.com/doi/book/10.4324/9781315649122

Bond, P. 2018b. The BRICS centrifugal geopolitical economy. Вестник Рудн. Серия: Международные Отношения. Vestnik Rudn. International Relations, 18, 3, pp.535-549, http://journals.rudn.ru/international-relations/article/view/20102

Bond, P. 2019. Degrowth, devaluation and uneven development from North to South. in E.Chertkovskaya, A.Paulsson and S.Barca (Eds), Towards a Political Economy of Degrowth. London: Rowman and Littlefield, pp.157-176, https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781786608963/Towards-a-Political-Economy-of-Degrowth

Bond, P. 2020. Who really ‘state-captured’ South Africa?, in E. Durojaye and Mirugi-Mukundi (Eds), Exploring the Link between Poverty and Human Rights in Africa, Pretoria, Pretoria University Law Press, pp.59-94, http://www.pulp.up.ac.za/images/pulp/books/edited_collections/poverty_and_human_rights/Chapterpercent204.pdf

Borderless Hong Kong 2017. Invitation to a Hong Kong seminar. Hong Kong, 22 August. https://intercoll.net/Invitation-to-a-Hong-Kong-seminar-on-The-BRICS-and-One-Belt-One-Road-2-3

Bruce, P. 2016. Thick end of the wedge. Business Day, 22 January. http://www.bdlive.co.za/opinion/columnists/2016/01/22/thick-end-of-the-wedge-oops-zuma-on-slope-slips-in-snow

Chen, M. and L.Chuanhao (2018), Foreign Investment across the Belt and Road. Policy Research Working Paper 8607. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Chuang, J. 2016. Factory girls after the factory: female return migrations in rural China, Gender and Society, 30, 3.

CNN. 2017. The Chinese connection to the Zimbabwe coup. 18 November. https://edition.cnn.com/2017/11/17/africa/china-zimbabwe-mugabe-diplomacy/index.html

Committee to Protect Journalists. 2017. China sentences journalist Lu Yuyu to four years in prison. New York. 4 August. https://cpj.org/2017/08/china-sentences-journalist-lu-yuyu-to-four-years-i/

Delta BEC. 2020. Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone Designated Site: Environmental Impact Assessment Report. Polokwane, September. https://deltabec.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/P17102_REPORTS_25_REVpercent2000-Draft percent20environmental percent20impact percent20assessment percent20report.pdf

Ding, D., F. Di Vittorio, A. Lariau and Y. Zhou. 2021. Chinese Investment in Latin America: Sectoral Complementarity and the Impact of China’s Rebalancing. IMF Working Paper, Washington, International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2021/English/wpiea2021160-print-pdf.ashx

Hung, H. 2015. China fantasies. Jacobin, December. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/12/china-new-global-order-imperialism-communist-party-globalization/

Hung, H. 2018, Xi Jinping’s absolutist turn. Catalyst, 2. https://catalyst-journal.com/vol2/no1/xi-jinpings-absolutist-turn

Garcia, A. & Bond, P. 2018. Amplifying the contradictions: The centrifugal BRICS. in L.Panitch and G.Albo (Eds), The World Turned Upside Down: Socialist Register 2019, London, Merlin Press, 2018, pp.223-246, http://www.merlinpress.co.uk/acatalog/THE-WORLD-TURNED-UPSIDE-DOWN–SOCIALIST-REGISTER-2019.html

Heurlin, C. 2016. Responsive Authoritarianism in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hongwi, W. 2017. Where is Zimbabwe headed after shift? Global Times, 16 November. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1075611.shtml

International Monetary Fund 2017a. China: Article IV Consultation, Washington, DC, http://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2017/08/15/pr17326-china-imf-executive-board-concludes-2017-article-iv-consultation

International Monetary Fund 2017b. The walking debt: Resolving China’s zombies. IMF Blog, Washington, DC, 11 December. https://blogs.imf.org/2017/12/11/chart-of-the-week-the-walking-debt-resolving-chinas-zombies/

International Monetary Fund 2020. China: Article IV Consultation Staff Report, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2021/01/06/Peoples-Republic-of-China-2020-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-49992

Lin, K. 2015. Recomposing Chinese Migrant and State-Sector Workers. in Chinese Workers in Comparative Perspective, edited by Anna Chan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015),

Luxemburg, R. 1913. The Accumulation of Capital. New York: Routledge. https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1913/accumulation-capital/ch27.htm

Marini, R.M., 1972, Brazil Subimperialism Monthly Review 23 (9), Available at: https://monthlyreviewarchives.org/index.php/mr/article/view/MR-023-09-1972-02_2/0.

Matsakis, L. 2019. How the West Got China’s Social Credit System Wrong. Wired, 29 July. https://www.wired.com/story/china-social-credit-score-system/

Mazibuko, P. 2015. Dalai Lama threat to China, SA’. Independent Online, 28 December https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/dalai-lama-threat-to-china-sa-1964436

McKinsey Global Institute, 2019. Globalization in Transition, New York, January. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/innovation-and-growth/globalization-in-transition-the-future-of-trade-and-value-chains

O’Neill, J. 2001. Building better global economic BRICs. New York: Goldman Sachs Global Eocnomics Paper 66, http://www.elcorreo.eu.org/IMG/pdf/Building_Better_Global_Economic_Brics.pdf

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2019. Society at a Glance 2019. Paris. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/soc_glance-2019-en.pdf?expires=1606762391&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=D6DA63176DC444944B2224B094A8EBEA

Pilger, J. 2016. The Coming War on China. New Internationalist, 30 November. https://newint.org/features/2016/12/01/the-coming-war-on-china/

Reuters 2014. South Africa denies Dalai Lama visa again. 5 September, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-safrica-dalailama-idUSKBN0H00MZ20140905

Ryan, E. 2019. Musina Makhado SEZ hosts packed investment conference to transform Limpopo’s economy, Mail&Guardian, 6 December. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/mail-guardian/20191206/textview

Shixue, J. 2011. China’s principles in foreign aid. Global Times, 29 November. http://www.china.org.cn/opinion/2011-11/29/content_24030234.htm

The Economist. 2014. An interview with the President. 2 August. https://www.economist.com/democracy-in-america/2014/08/02/an-interview-with-the-president

The New York Times. 2019. The Xinjiang Papers. 16 November. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html

Toussaint, E., Mbangula, M. D’Sa, D. Thompson, L. and Bond, P. 2019. Shifting Sands of the Global Economic Status Quo. African Centre for Citizenship and Democracy Policy Paper #2/2 on South Africa’s Special Economic Zones in Global Socio-Economic Context. November. https://accede.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ACCD percent20& percent20FES percent20Policy percent20Working percent20Paper percent20No.2-draft percent20version.pdf

UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2019. World Investment Report 2019. Geneva. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2019_en.pdf

Xi, J., 2015. Jointly build partnership for bright future. Speech to the 7th BRICS Heads-of-State Summit, Ufa, Russia, 9 July. https://brics2017.org/English/Headlines/201701/t20170125_1402.html

Xi, J., 2017. Opening plenary address. World Economic Forum, Davos, 17 January. https://www.weforum.org/events/world-economic-forum-annual-meeting-2017/sessions/opening-plenary-davos-2017.

Zhang, X. (2017), Chinese Capitalism and the Maritime Silk Road, Geopolitics, 22, 2, 2017, pp.310-331, DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2017.128937

Featured image: “President Cyril Ramaphosa at 2018 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation” by GovernmentZA is licensed with CC BY-ND 2.0.