Is China Capitalist?

Judging by what has been said or written about China, both on the right and on the left, socialism there is finished. The country is assumed to have capitulated and become capitalist, whatever the Chinese leadership itself may say. It is this almost unanimous opinion that economists Rémy Herrera and Zhiming Long challenge with fervour in their book La Chine est-elle capitaliste?

Importance

For the left, the issue is of the utmost importance. First of all, it concerns almost a quarter of the world’s population and one of the few remaining states that have resulted from a socialist revolution. The direction that China is pursuing will help to determine the future of this planet.

In addition, that what is at stake is also very important for the battle of ideas here. China’s socio-economic development is an impressive success story. Now that capitalism shows unmistakable signs of decline, it has every interest to claim the Chinese success story as “capitalist”. This way it can both take some ideological credit and discourage the forces of dissent. Through neoliberal pensée unique, mainstream ideological conformism, no stone is left unturned in convincing people that socialism has no future. A “socialist China” does not fit into that framework.

In the eye of the beholder

For sure there are a number of eye-catching phenomena that speak in favour of assessing China as an example of capitalism: the increasing number of billionaires, the consumerism affecting large sections of the population, the introduction of a lot of market mechanisms after 1978, the implantation of just about all major Western companies trying to turn the country into a huge capitalist workshop based on low wages, the presence of the big banks on Chinese soil, and the ubiquitous presence of Chinese private companies on international markets.

But, as Herrera and Long argue, if France or another Western country were to collectivize all agricultural land and mining; nationalize the infrastructure of the country; transfer key industries to the government; set up a rigorous central planning; if the government strictly controlled the currency, all major banks and all financial institutions; if the government also closely monitored the behaviour of all domestic and foreign companies; and as if that were not enough, if there was a communist party at the top of the political pyramid to supervise it all, would we still, without inviting ridicule, speak of a “capitalist” country? Undoubtedly not. We would perhaps label it as “socialist” or “communist”. Yet it is odd that people stubbornly refuse to stick those labels on the political-economic system operative in China.

In order to understand the Chinese system properly and not get caught up in superficial observations, the authors state, you must take into account a number of extraordinary features of the country. First of all there is the enormous amount of people involved and the vastness and diversity of the territory.

You also have to look at it from a perspective of the secular eras in which the nation and culture have taken shape. For example, for two thousand years the state has appropriated the added value of the farmers, strongly restricted private initiative and transformed large production units into state monopolies. During all those centuries there was no question of capitalism.

Finally, you must take into account the colonial humiliations of the second half of the nineteenth century and the particularly turbulent first half of the twentieth century, with three revolutions and the same number of civil wars. To give an example, during thirty years of civil war the Communist Party carried out numerous experiments in “liberated territory”, in which a significant proportion of the private sector was left intact to let it compete with the new collective forms of production.

Beyond stereotypes

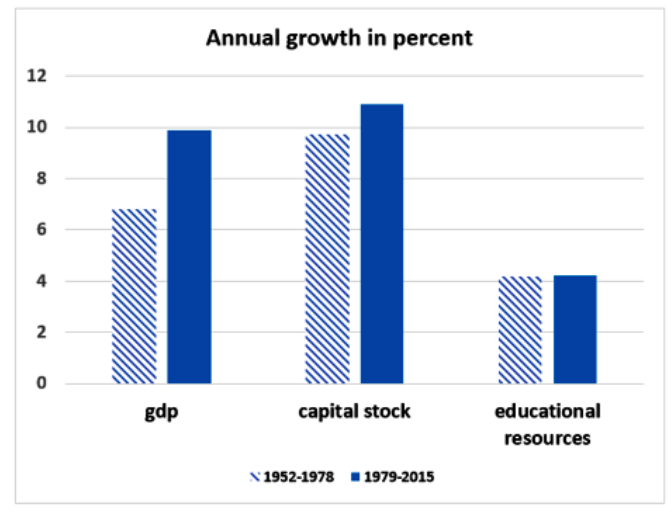

Before the authors analyse the characteristics of the system itself, they deal with two stubborn stereotypes about the Chinese success story. The first widespread cliché is that rapid economic growth has only come about since and thanks to the Deng Xiaoping reforms started in 1978. That is completely incorrect. In the ten years prior to that period, the economy had already experienced a very respectable growth rate of 6.8 percent, double the US growth in that period. If you look at the investments in production resources (capital stock) and know-how (educational resources) you see that the growth in both periods is about the same. In the first period growth in the field of Research & Development was even higher.

An essential element to explain the successes of China is its agricultural policy. China is one of the few countries in the world that has guaranteed access to agricultural land for its farming population. After the revolution, agricultural land came into government hands and every farmer was allocated a piece of land. That measure applies to this day. The agricultural issue in China is so pressing because the country has to feed almost 20 percent of the world’s population with only 7 percent of the fertile agricultural land. To give an idea of what this means: in China there is a quarter of a hectare of agricultural land per inhabitant, in India double that area and in the US 100 times as much.

China managed to feed its population fairly quickly, despite the blatant errors of the Great Leap Forward. Moreover, the added value created by agriculture was used in industry, thus laying the foundation for rapid industrial development. The spectacular growth of 9.9 percent in the post-reform period has only been possible on the basis of efforts and achievements during the first thirty years of the revolution. All in all, already under Mao the country developed in an impressive way. Under his leadership, per capita income tripled while the population nearly doubled. The authors also point out that in the initial phase the Chinese economy was not an autarky, nor did it deliberately fall back upon itself. Actually the country was suffering from an embargo from the West.

Then there is a second frequently heard cliché according to which the spectacular growth would be the natural and logical result of the opening up of the economy and of its integration into the capitalist world market, in particular since China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. That view is untenable too. Long before that accession, China experienced a strong economic growth: between 1961 and 2001 the annual average growth was 8 percent. The opening up was advantageous to the economy indeed, but the immediate increase in growth was anything but spectacular. In the first fifteen years after the accession to the WTO, economic growth increased only slightly more than 2 percent extra.

Opening up the economy to foreign countries – trade, investment and financial capital flows – has had disastrous consequences in many third-world countries. In China, this opening has been successful because it was subordinate to domestic needs and objectives, and because it was fully integrated into a solid development strategy. According to Herrera and Long, the Chinese development strategy has a coherence that is unequalled in the countries of the South.

Neither communism nor capitalism

What exactly is this “socialism with Chinese characteristics”? For the authors it is certainly not about communism in the classical sense of the word. Marx and Engels understood communism as the abolition of wage labour, the disappearance of the state and the self-government of producers. In present-day China this is not what is happening, just as it never was in actually existing socialist countries. In China, this was less the result of an ideological choice than of the extremely difficult circumstances in which the revolution came about and had to live up to. In 1949, after a long-standing civil war, a state established itself as “communist” and gradually distanced itself from the Soviet model.

After the opening up and the reforms under Deng Xiaoping, according to Herrera and Long, “socialism has retreated enormously in China”. Today, Chinese society is “far removed from the communist egalitarian ideal”. The authors refer to a number of aspects such as individualism, consumerism, favouritism, careerism, the craving for luxury and glamour, corruption, etc. These aspects are certainly disturbing, but the Chinese leadership is doing its utmost to restore “socialist morality”.

It is certainly not communism, but neither is it capitalism. For Marx, capitalism presupposes a strong separation between labour on the one hand and ownership of the most important means of production on the other. The owners of capital tend to become collectives (shareholders) of people who no longer directly manage the production process, but leave that to managers. Earnings often take the form of dividends on shares.

The vast majority of the incredibly large number of small Chinese enterprises – mostly family or artisan owned businesses – certainly do not meet that criterion. Nor does the criterion apply to the many “collectively owned” companies where the workers own part of the production equipment and have a voice in its management, and it is not in the least applicable to the cooperatives. Even in public companies, the separation between labour and property is not that clear. Because there too there is a certain, albeit limited, form of participatory management for blue-collar and office workers. In short, the separation between labour and property is often very relative.

Another important criterion for a society to be capitalist is the maximization of individual profit. In any case, this does not apply to the large state-owned companies, where the most important means of production are allocated.

No capitalism, then, but perhaps state capitalism? According to the authors that concept comes close, but it is too vague and a catch-all term.[i]

If not, then what?

The top leaders of China do not deny the existence of capitalist elements in their economy, but they see this as one of the components of their hybrid system, the key sectors of which are in the hands of the government. For them, China is still in “the first phase of socialism, a stage considered essential to develop the productive forces”. The historical goal is and remains that of advanced socialism. Like Marx and Lenin, they refuse to regard communism as “the sharing of poverty”. Hence “their will to pursue a socialist transition during which a very large majority of the population will have the opportunity of accessing wealth”. “Wouldn’t we prove at the same time that socialism can, and must, surpass capitalism?” the authors wonder.

Herrera and Long describe the political-economic system in China as a system of “market socialism”. Such a system is based on ten pillars, which largely don’t exist in capitalism:

- The sustainability of a powerful and modernized planning; which is no longer the rigid and hyper-centralized system of bygone days.

- A form of political democracy, clearly perfectible, but enabling the collective choices that are found to be the basis of this planning.

- The existence of very extensive public services, most of which remain outside the market.

- Ownership of land and natural resources that remain in the public domain.

- Diversified forms of property, suitable for the socialization of the productive forces: public enterprises, small individual private property or socialized property. Capitalist property is maintained during a long socialist transition, even encouraged, in order to stimulate overall economic activity and to encourage efficiency in other forms of property.

- A general labour policy of increasing wages relatively more rapidly compared to other sources of income.

- The stated desire for social justice from an egalitarian perspective promoted by the authorities, going against a several-decades-old trend towards social inequalities.

- Priority given to the preservation of the environment.

- A concept of economic interstate relations based on a win-win principle.

- Political interstate relations based on the systematic search for peace and more equitable relations between peoples.

Some of those pillars are addressed in more detail. We go through two of them here: the key role of state-owned companies and modernized planning. Moreover the book addresses the important issue of the relationship between political and economic power.

State-owned companies play a strategic role in the whole of the economy. They operate in a way that is not at the expense of the many small private companies and the industrial structure of the nation. They are focused on productive investments and can easily and inexpensively provide services to other companies and collective projects. In these companies, the government can also decide for itself which form of management is most appropriate. The key role that government companies play is one of the essential explanations for the good performance of the Chinese economy. They also play their role on a social level. The state-owned companies can give their employees higher wages and good social benefits. It is in that sector that the best opportunities are found to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor.

Economic planning is “the actual space in which a nation chooses its common destiny and the means for a sovereign people to become the master of that destiny”. According to the authors, in China there is a “powerful” planning, the techniques of which have been relaxed, modernized and adapted to present-day requirements. In the planning of the past, which was overly centralized, a company had to accept products, regardless of the quality or real cost at which they had been produced. This mechanism greatly limited the initiative of companies and also the efficiency of the productive sector as a whole. Quality and cost were seen as “administrative” or “technocratic” problems and lost their capacity to stimulate the economy. The coercion and limitations in manufacturing manifested themselves through recurring crises of availability of goods and material resources.

From the 1990s onwards, planning has become more flexible, monetarized and decentralized. That planning was still drawn up under the direction of a central macroeconomic authority. The companies were given more autonomy to manage foreign currencies and to purchase goods. Thanks to this relaxation it has been possible to solve a number of deficiencies of the old planning and this has led to an economic development that is more intensive[ii] and more respectful of the environment.

Does the transition to socialism require that economic and political power coincide completely? The authors believe it does not. It is, however, necessary that the owners of economic power – the capitalists – come under the strict supervision of political power. The authors refer to a discussion between Mao Zedong and the then Soviet leadership in 1958. According to Mao, the Chinese revolution could continue its course, even though there were still capitalists in China. His argument was that the capitalist class no longer controlled the state, but that this was now done by the Communist Party.[iii] Today, according to Herrera and Long, the proprietors of national private capital are effectively restricted in their ambitions through a very powerful public ownership of the strategic sectors. Moreover, the Communist Party is still able to prevent the bourgeoisie from becoming a dominant class again.

What will the future bring?

The authors’ judgement on the Chinese trajectory remains undecided. A continuation of the road towards socialism is possible, but a restoration of capitalism is not to be excluded. The outcome will be chiefly determined by class struggle. Class relations in today’s China are complex. On the one hand, you have the Communist Party that relies mainly on the middle class and the entrepreneurs. In recent decades both sections of the population benefited most from strong economic growth. On the other hand, you have the large strata of workers and peasants who continue to believe in the possibility of being masters of their collective future and who still have hope of a socialist future.

The question now is whether the party will succeed in extending its success story without changing the balance of power in favour of the workers and peasants. If the party takes the path of capitalism, it risks upsetting the fragile balance. This could lead to major political confrontations and a loss of control over the contradictions of the system, and at the same time to a failure of the long-term development strategy.

The outcome is uncertain. But for the authors there are a lot of aspects that distinguish China’s system from capitalism. In addition, there is also the long-term objective of socialism and there is a lot of potential to reactivate that project.

Another uncertain factor that may determine the future is financial monopoly capitalism, based on a US military hegemony which increasingly seeks confrontation with China, despite the strong economic interdependence between the two countries. Herrera and Long warn that people in the West must be well aware that world capitalism is at an impasse and “that in its decline it will cause nothing but social devastation in the North and wars in the South”.

We may add that it is to be hoped China’s capitalist logic can be checked. Otherwise we will almost certainly end up in a situation similar to that of the eve of WWI, where imperialist blocs were heading for a mutual showdown in order to expand or retain their spheres of influence.

The story sketched by the authors is not a triumphant one. “Socialism with Chinese characteristics” is by no means a “finished ideal of the communist project”. For it to be like that there are too many “shocking imbalances” in the project. Herrera and Long note that China is still a developing country and that it will therefore go through a “long and difficult process, full of contradictions and risks”. This should not come as a surprise, because capitalism also “took ages to consolidate”. Anyway, the many disparities and contradictions should discourage sympathizers from applying the Chinese recipe elsewhere.

A few comments

Herrera and Long are academics, but know how to present their arguments in a very readable and convincing way. The book contains strong and new figures and also a lot of useful graphs. In one of the annexes you will find a very interesting timeline of China’s history that starts at the beginning of human history. A downside is that not all argumentation is worked out equally well; the book is too concise for that.

The perspective is economic. The advantage of this is: a materialist approach, no woolliness. The disadvantage is that the authors may have a tendency to underrate the role of ideological struggle. Although Herrera and Long point out a number of negative aspects in this field, they underestimate the fact that the whole of society up to and including the Communist Party is permeated by capitalist propaganda. That came to light, for example, in the events surrounding Tiananmen. At the time China came very close to going the same way as the Soviet Union. Reducing capitalist ideology will be crucial for staying on course towards socialism.

In their argument about whether or not the system is capitalist, they focus on ownership relationships. That is correct, but only partly, because ownership relationships are not completely indicative of the government’s control over the economy. By either granting or not granting access to procurement contracts, tax breaks, to public investment funds, financial institutions and grants, etc., central government controls entire sectors including private companies, without having direct control over individual companies or holding shares in them.[iv]

For various reasons, China is one of the most misunderstood countries in the world. Therefore Herrera and Long’s work is more than welcome. It courageously goes against the tide and disproves a number of stubborn prejudices. In the light of the relative decline of capitalism, both economically and politically, the authors bring the ideological debate into focus. That is the second reason why the book is highly commendable.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Rémy Herrera & Zhiming Long, La Chine est-elle capitaliste?, Paris: Éditions Critiques, 2019, 199 pages.

Translated by Dirk Nimmegeers

Notes

[i] The term state capitalism is by no means an unequivocal concept about which there is unanimous consent. Below are some systems that the term can refer to:

- The state undertakes commercial and profitable activities, government companies exercise capitalist management (even though the state calls itself socialist).

- Strong presence or dominance of state-owned companies in a capitalist economy.

- The means of production are privately owned, but the economy is subject to economic planning or supervision. Cfr. New Economic Policy (NEP) under Lenin.

- Variant: the state has considerable control over the allocation of credits and investments.

- Another variant: the state intervenes to safeguard the interests of its monopolies (state monopoly capitalism).

- Another variant: the economy is largely subsidized by the state, which also takes on strategic Research & Development.

- The government manages the economy and behaves like a single large company that derives the added value from labour to reinvest.

Sources: MilibandR., Political theory of Marxism, Amsterdam, 1981, p. 91-100; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_capitalism.

[ii] Extensive development is quantitative growth, more of the same by deploying more people and machines or making them work more. Intensivedevelopment is qualitative growth based on higher productivity.

[iii] “There are still capitalists in China, but the state is under the leadership of the Communist Party”. Mao Zedong, On Diplomacy, Beijing 1998, p. 251.

[iv] See, for example, Hsueh R., China’s Regulatory State. A New Strategy for Globalization, Ithaca 2011; Zhao Zhikui, Introduction to Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, Beijing 2016, chapter 3; Kroeber A., China’s Economy. What Everyone Needs to Know, Oxford 2016, chapter 5; Porter R., From Mao to Market. China Reconfigured, London 2011, p. 177-184; Naughton B., “Is China Socialist?”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 31, no. 1 (Winter 2017), pp. 3-24, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44133948?seq=5#metadata_info_tab_contents.