African American Resistance in the Rural South

After the overthrow of Reconstruction, the institutionalization of tenant agriculture prompting the Great Migration, Black farmers continued to seek avenues of redress and self-organization against exploitation and oppression

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (desktop version)

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

“The new industry had a vision not of work but of wealth, not of planned accomplishment, but of power. It became the most conscienceless, unmoral system of industry which the world has experienced. It went with ruthless indifference towards waste, death, ugliness and disaster, and yet reared the most stupendous machine for the efficient organization of work which the world has ever seen.” Quote taken from “Black Reconstruction in America” by Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois in the chapter entitled “Looking Forward”. (See this)

During the most disastrous post-Civil War period of African American historical development in the rural South and other regions of the United States, there were heroic efforts to reverse the process of re-enslavement which utilized brute force, super-exploitation and the passage of reactionary legislation often referred to as the Black Codes.

These Black Code laws were designed to suppress the political and economic aspirations of the formerly enslaved Africans who by their efforts during the Civil War and Reconstruction, sought to build an independent social existence in the U.S.

However, this notion of equality and self-determination clashed with the desire on the part of the planters and their allies among the white population to restore the absolute dominance of the slavocracy. African American suffrage and land ownership were viewed by the white southerners as a threat to their ruling class status.

White militias founded by former slave owners and Confederates such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) inflicted terror on the African American people. Between the 1880s and the Great Depression of the 1930s, thousands of Black people were lynched in the U.S. These acts of terrorism were justified through false claims of insolence, robbery, rape and murder against the whites.

In recent years, official tabulations of the actual number of lynchings in the U.S. remain inconclusive. Many acts of racial terror were covered-up as justifiable homicide by law-enforcement agents, white posses and the decisions of racist courts which imposed capital punishment.

The so-called “race riots” of the early 20th century in urban areas such as New Orleans (1900), Atlanta (1906), Springfield (1908), among others, were in actuality organized acts of systematic repression often incited and inflamed by white ruling class interests committed to the maintenance of their supremacy over Black labor. In the rural areas of the South such as in Mississippi, South Carolina, Louisiana, Tennessee and other post-Confederate and slave states, there were numerous massacres and forced removals of African Americans which were prompted by the desire to crush all forms of resistance and self-organization.

Populism and the African American National Question

During the 1890s, the People’s Party, or Populist Movement, was formed ostensibly to organize in the rural areas of the South to challenge the largely uncontested power of landowners in alliance with industrialists. The movement would become a viable force up until the first decade of the 20th century when it succumbed to the racism so prevalent in the U.S., particularly in the southern states.

The origins of the white farmers’ movement can be traced back to the late 1870s as the South emerged from the years of Federal Reconstruction. A Southern Farmers Alliance dominated by whites from various stratums within the agricultural industry refused to allow African Americans to join their organization.

Consequently, African American farmers, both sharecroppers and small landowners, formed their own organizations. One of the most prominent was The Colored Farmers National Alliance and Cooperative Union (CFNACU) founded in December 1886 in Houston County, Texas. Initially, the CFNACU had the support of R.M. Humphrey, a white Farmers Alliance member and Baptist missionary. Humphrey even served as a spokesman for the CFNA in an effort to temper the inevitable racist backlash against the organization of African American farmers. (See this)

The CFNACU would merge with two other farmers organizations in the African American community. These groups were the National Colored Alliance and the Colored Agricultural Wheels which operated in Arkansas, West Tennessee and Alabama. By 1890, these Black farmers organizations claimed a membership of 1.2 million people.

In September 1891, sections of the African American farmers organizations called a “cotton pickers strike” in Lee County, Arkansas. This action was met with extreme repression leading to an armed confrontation and the arrests and murders of at least 11 African Americans and a white plantation manager killed ostensibly by the strikers.

Nonetheless, differences between white and Black farmers organizations would hamper the capacity of any serious coalition. The Populist Party began by claiming their desires to organize both African American and white farmers. The grouping organized chapters in the Southern and Western regions of the U.S.

However, despite their emergence as a viable Third Party during the 1890s which challenged electorally the Democrats and Republicans, eventually leading figures in the People’s Party such as Tom Watson, abandoned any suggestion of an alliance with African Americans and became advocates of white supremacy.

The Populist Party would soon oppose efforts to guarantee the franchise to African Americans since this harkened back to the years of Federal Reconstruction. In North Carolina, there was a viable coalition of white populists and Black farmers allied with the Republican Party during the mid-1890s resulting in the ascendancy to local offices by African American politicians.

Nevertheless, this alliance was overthrown by force in the Wilmington coup of 1898, instituting Jim Crow laws which had become the norm throughout the South in the decades following the Civil War and Reconstruction. Hundreds of African Americans were massacred in the areas around Wilmington by white segregationist officials and vigilantes. These events remained largely hidden until recent years when the acknowledgement of these atrocities came to light on an official level.

Racial Terror in Elaine, Arkansas in 1919

After the conclusion of World War I, there was a rash of attacks against the African American communities across the U.S. in both rural and urban areas. Designated as “Red Summer”, African American neighborhoods were violently attacked in cities such as Chicago, Washington, D.C., Knoxville, Tennessee, etc. Dozens of people were killed and injured while others were driven out of these municipalities and given long term prison sentences.

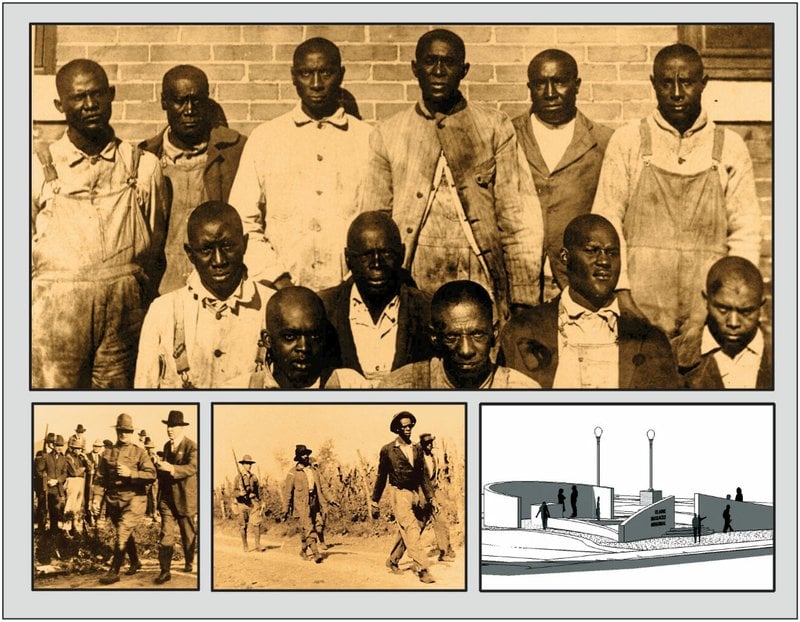

Elaine Arkansas Black defendants during 1919

However, in the rural areas of the South, these incidents of racial terror took on even more murderous proportions. In Phillips County, Arkansas, African American tenant farmers, sawmill employees and domestic workers sought to form an organization aimed at enhancing their standard of living in the immediate aftermath of WWI.

The Progressive Farmers and Household Union (PFHU) was formed in 1918 and grew rapidly among African American men and women. The organization was committed to gaining greater returns on their cotton crops where prices were increasing after the War. African American tenant farmers and domestic workers were being severely exploited through the agricultural production system.

Despite the large volumes of cotton being cultivated, these farmers and domestic workers were forced to sell their crops and labor to the white-owned firms which refused to provide any accounting for their products and purported debts owed. Every year these farmers and domestic workers would be assessed as being in serious debt and therefore obligated to pay high interest rates to the landowners and merchants.

In 1918-19, an African American named Robert Hill led an effort to withhold the labor of domestic workers and the cotton produced by the farmers. On September 30, 1919, they announced a mass meeting at a lodge in Elaine, Arkansas to explain their plans. The PFHU had hired a law firm in Little Rock to provide legal support to achieve their demands for higher wages and the acquisition of farmland.

At a location in Elaine called Hoop Spur where the meeting was convened, a white mob attacked the gathering which was guarded by armed African Americans. An ensuing gunbattle resulted in the deaths of at least one white man. In retaliation, law-enforcement agents and federal authorities led by the Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough, indiscriminately killed and arrested hundreds of African American farmers and workers. Estimates from the time period suggest that anywhere between 100-300 African Americans were killed along with five whites.

Hill was able to flee to neighboring Kansas where the then Governor Henry Justin Allen refused to extradite him back to Arkansas, declaring that it would not be possible for him to receive a fair trial in the state. 12 African American farmers designated by the Arkansas authorities as ringleaders of the effort were placed on trial by an all-white jury and sentenced to long prison terms and death by execution.

These injustices received widespread coverage in the African American and mainstream press. Several organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Equal Rights League and the People’s Movement of Chicago passed resolutions and pledged support to save the men’s lives and win their freedom.

African American journalist, organizer and anti-lynching crusader, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, left her Chicago residence to travel to Phillips County, Arkansas. Wells-Barnett interviewed the wives of the defendants then being held in jail. She then went to the jail and interviewed the inmates exposing the actual story behind the so-called “Arkansas Riot”. The Union and its supporters were accused of insurrection through a plot to kill all the white residents of Phillips County and seize the land.

Wells-Barnett in her study of the incident published as “The Arkansas Race Riot” in 1920, noted that:

“The terrible crime these men had committed was to organize their members into a union for the purpose of getting the market price for their cotton, to buy land of their own and to employ a lawyer to get settlements of their accounts with their white landlords. Cotton was selling for more than ever before in their lives. These Negroes believed their chance had come to make some money for themselves and get out from under the white landlord’s thumb.”

Eventually, through a massive legal campaign and political pressures exerted on the Arkansas state courts and the U.S. Supreme Court, the 12 African American inmates were released. Hill, the principal organizer, remained in Kansas where he would work until retirement for the railroad industry.

Legacy of Resistance Must Be Upheld

These examples of African American self-organization and resistance to racial terror, national oppression and economic exploitation illustrate the continuity of struggle in the U.S. African Americans were never totally suppressed and a century later these questions of independent organization and alliances with white farmers and workers remain unresolved.

In future articles, we will examine other efforts aimed at organizing African Americans in rural and small town areas and their impact on the further urbanization of population groups in the U.S. During the period of the Great Depression leading into World War II and the advent of the mass Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, the plight of African Americans and their resistance to oppression continued to be an important aspect of the political culture of the U.S.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Abayomi Azikiwe is the editor of the Pan-African News Wire. He is a regular contributor to Global Research.

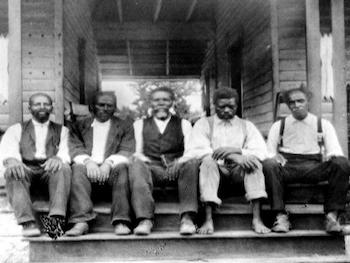

All images in this article are from the author; featured image: African American Farmers Alliance of the late 19th century