We Saved Net Neutrality Once. We Can Do It Again

Just a few years ago, powerful grassroots pressure rose up to protect a free and open internet.

Democracy lives or dies on the quality of public conversation. “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government,” Thomas Jefferson wrote, “I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

Today it doesn’t take the smarts of a Jefferson to realize that our public conversation, filtered through corporate-controlled, often-fractured media, is faltering. While analyzing how to fix our broken news system, from the promotion of public broadcasting to eliminating fake news, is complex, right now is a critical moment to hold the line. If we hope to reinvigorate our media, today democracy defenders are called upon to play defense—and quickly.

Earlier this month, Federal Communications Commission Chairman Ajit Pai proposed a plan to dismantle net neutrality, an extremely worrying move—one that has provoked the ire of organizations and citizens across the country. And this Thursday, the commission will vote on the plan.

If you’ve heard the term “net neutrality,” is it something you imagine only internet fanatics can grasp? Not at all. It simply refers to baseline protection ensuring that no internet service provider can “interfere with or block web traffic, or favor their own services at the expense of smaller rivals.” As such, it is integral to democratic dialogue. To abolish it, explains Craig Aaron, president and CEO of the media advocacy group Free Press, “would end the open nature of the internet and leave activists, media makers and all the rest of us at the mercy of the biggest phone and cable companies.”

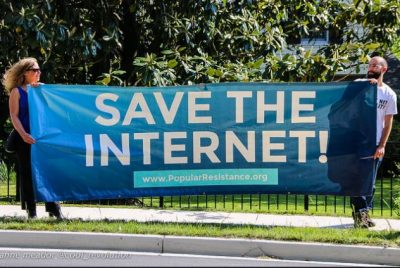

Image: “Recently, more than half a million people called Congress about net neutrality and approximately the same number filed comments on the FCC website.” (Photo: Joseph Gruber/Flickr/cc)

Needless to say, given the current composition of the FCC, the fate of net neutrality looks bleak.

Yet, the recent history of net neutrality offers an encouraging story of the power of the people to protect the core democratic principle of free exchange and shows that even if things look bad, grassroots pressure holds the key to saving the internet as we know it.

The story starts in 2010. That December, the FCC passed what those most concerned considered pretty weak half-measures prohibiting internet service providers from blocking websites or imposing limits on users, Aaron says. And by 2014, a federal lawsuit brought by Verizon succeeded in striking down even this half-measure. Verizon’s hubris ignited a massive call for the FCC to fight back. Protests demanded even stronger rules to reclassify internet service providers as “common carriers,” requiring them to act as neutral gatekeepers to the internet and to protect access for all.

By May 2014, inspired by the Occupy Wall Street protests, concerned citizens had set up camp in Washington, D.C., at the FCC headquarters. It had all started with a protest organized by Margaret Flowers and Kevin Zeese. Flowers, a pediatrician who cut her teeth in the fight for universal health care, and Zeese, a lawyer who fought injustices in the 1980s’ war on drugs, announced at the protest’s end that they were not going to leave. The duo rolled out their sleeping bags on the grass, stayed the night, and before they knew it, the occupation grew drastically. Fellow concerned citizens flooded in with tents and banners. One day followed the next, each to the tune of passing cars honking in solidarity. Not only did employees of the FCC come out to thank the occupiers, but three of the five FCC commissioners came to meet Flowers and Zeese.

A week later, then-FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler put out a “notice of proposed rule-making” that asked the public, “What is the right public policy to ensure that the internet remains open?” The preferred solution put forward by the FCC, outlined in the notice, would have left the door ajar for a “two-tiered internet” plan, wherein internet service providers could sell content providers priority access to their subscribers at rates only big companies could afford. Citizen reformers couldn’t and wouldn’t get behind this proposal.

But the notice also sought public comment on whether the FCC should “reclassify” the internet as a common carrier under the law. Doing so would give the FCC greater legal authority over providers to fully and truly keep the internet open. This request for comments gave citizens, especially those emboldened by the FCC occupation, an opening.

For months citizens continued protesting and spreading awareness about the importance of net neutrality. Leading up to the closing of the comment period in September 2014, the activist group Fight for the Future parked a Jumbotron outside FCC headquarters. The giant video billboard played videos of fellow citizens explaining why net neutrality mattered to them. Later, reformers performed a skit outside the FCC, a “Save the Internet Musical Action.” The musical’s chorus—“Which side are you on, Tom? Which side are you on?”—would soon be answered.

These courageous public actions built on the momentum sparked by the FCC occupiers. Together, they galvanized citizens to submit 4 million comments to the FCC. The FCC chairman reversed his position, endorsed strong rules, and moved to restore the agency’s authority. In February 2015, the FCC announced it would reclassify internet service providers as common carriers. Wheeler called it “the proudest day of my public policy life.” Another FCC commissioner called it “democracy in action.”

The victory taught one very important lesson. As Flowers put it, “it showed we don’t have to compromise. We can actually stay true to what we are fighting for and win.” For that win, a broad coalition of citizen power united folks ranging from the tech industry—such as Netflix and Tumblr—to the Black Lives Matter movement. They all understood the democratic value of a free internet on which independent media is kept accessible and online grassroots organizing is made possible. “This cross-generational and multi-issue movement was critical in pressuring the FCC commissioners and lawmakers to support net neutrality,” Aaron says.

The situation in which we find ourselves today is different from how it was in 2014. The composition of the FCC has changed, and, after a year of resisting President Trump’s agenda, many perceive grassroots activists to be tired. Yet, the takeaway from the above story is that citizens have untold political power and, when they effectively wield it, can influence even politically removed bureaucrats to win major democratic victories.

Countless Americans are already rising to the challenge. Recently, more than half a million people called Congress about net neutrality and approximately the same number filed comments on the FCC website. Moreover, on Tuesday, activists across the country began a “Break the Internet” campaign to raise as much awareness about the issue as possible before the FCC’s critical vote. According to Aaron, “public awareness has never been higher.”

This grassroots pressure will have to be sustained and significantly expanded to save the internet. And even if the FCC votes to repeal net neutrality, the fight must continue. Concerned Americans will have to pressure Congress to pass a bill to overturn the FCC decision. The fate of democracy depends on it.