U.S. Veterans Reveal 1962 Nuclear Close Call Dodged in Okinawa

Ota Masakatsu’s horrifying account of an erroneous order to launch nuclear missiles in Okinawa during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 raises the possibility that, despite the U.S. military’s vehement denials, a nuclear war could start by accident. While much discussion has centered on the Cuban Missile Crisis spinning out of control into nuclear war, the latest revelations link 1950s Okinawa as yet another site in which the possession of U.S. nuclear weapons came close to bringing nuclear holocaust.

Describing an earlier incident in Okinawa, veterans of the Nike-Hercules surface-to-air missile battery at Naha Airbase recalled an accidental firing during a circuits test in 1959, that was blamed on stray voltage. The missile left the launcher, smashed through a fence, and plunged down to the beach below where the warhead bounced out and skidded across the water “like a stone,” but did not detonate. The rocket blast killed two technicians and injured one. (“Nike History: Eyewitness Accounts of Timothy Ryan, Carl Durling and Charles Rudicil,” retrieved November 11, 2012, posted at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MIM-14_Nike_Hercules)

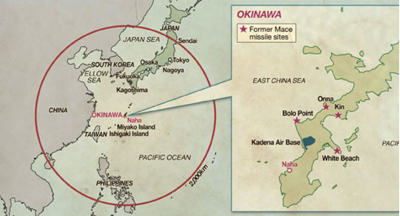

While U.S. bases were scattered throughout Japan, it was only in Okinawa that nuclear weapons were stored and warheads mounted on rockets. This was one, and perhaps the most dangerous, way that the disproportionate burden carried by this small island prefecture, where two-thirds of the total U.S. military presence in the country remains, weighed so heavily. Along with the risk of “reactivation” is the troubling possibility of serious environmental hazards at former nuclear sites in Okinawa. These include the village of Henoko, now also threatened by the planned construction of a U.S. Marine airbase in the face of deep Okinawan opposition from the grassroots to the Governor. Robert S. Norris, William M. Arkin, and William Burr reported in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists (November/December, 1999, pp. 26-35) that “Okinawa hosted 19 different types of nuclear weapons during the period 1954-1972.” The “secret agreement” accompanying the 1969 reversion pact between President Nixon and Prime Minister Sato identified nuclear weapons sites at “Kadena, Naha, Henoko, and Nike-Hercules units.” The agreement specified that the U.S. “requires standby retention and activation [of the sites] in time of great emergency.”

Steve Rabson is professor emeritus of East Asian studies, Brown University, and a Japan Focus associate. His latest book is The Okinawan Diaspora in Japan: Crossing the Borders Within (University of Hawaii Press, 2012). He was stationed in Okinawa as a U.S. Army draftee during 1967-68.

Okinawa and atom bombs: A Timeline (by Jon Mitchell)

1945 – U.S. military seizes control of Okinawa on June 23rd, fighting continues for several months

1952 – Treaty of San Francisco ends U.S. occupation of mainland Japan but affirms continued U.S. military rule over Okinawa

1954 – crew of the Lucky Dragon #5 are irradiated when the U.S. tests a powerful H-bomb at Bikini in the Pacific. More than 30 million Japanese people sign a petition in protest. U.S. military secretly stations first nuclear weapons on Okinawa

1956 – Ryukyu Assembly of Elected Officials demands the withdrawal of all nuclear weapons from the island

1962 – first of four Mace missile sites becomes operational at Bolo Point, Okinawa.

1965 – U.S. loses hydrogen bomb from the U.S.S. Ticonderoga 130 km off Okinawa’s coast

1966 – Iejima Island residents successfully block the deployment of Nike nuclear missiles

1967 – PM Sato Eisaku first suggests Japan’s three non-nuclear principles – not to possess, manufacturer or allow the introduction of atomic weapons

1968 – B-52 crashes near nuclear warhead bunkers on Kadena Air Base

1969 – Japan and the U.S. conclude a secret agreement which allows America to re-introduce nuclear weapons to Japan during times of crisis

1971 – Washington demands Tokyo help to pay for the removal of nuclear arms from Okinawa – the first official U.S. admission of the presence of nuclear weapons on the island

1972 – Okinawa reverts to Japanese administrative control with U.S. military bases intact

U.S. Veterans Reveal 1962 Nuclear Close Call Dodged in Okinawa

At the final moment of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, the U.S. nuclear missile men in Okinawa received a launch order which was later found to have been mistakenly issued, according to testimonies by former U.S. veterans given to Kyodo News.

In the fall of 1962, the Soviet Union introduced nuclear missiles into Cuba from where Moscow could target the mainland of the United States. U.S. President John F. Kennedy and his top advisers then seriously considered military options as a countermeasure, and the two superpowers were on the brink of nuclear exchanges.

The testimonies by the veterans, who gazed into the “abyss” of a nuclear war, shed new historical light on a nuclear close call which could have triggered the use of nuclear weapons, highlighting the potential risk of an accidental nuclear launch.

According to John Bordne, 73, former member of the 873rd Tactical Missile Squadron of the U.S. Air Force, several hours after his crew took over a midnight shift from 12 a.m. on Oct. 28 in 1962 at the Missile Launch Control Center at Yomitan Village in Okinawa, a coded order to launch missiles was conveyed in a radio communication message from the Missile Operations Center at the Kadena Air Base.

Another former U.S. veteran who served in Okinawa also recently confirmed on condition of anonymity what Bordne told Kyodo News in an interview last summer and in following e-mail exchanges. Bordne has mentioned the incident in an unpublished memoir based on his diary.

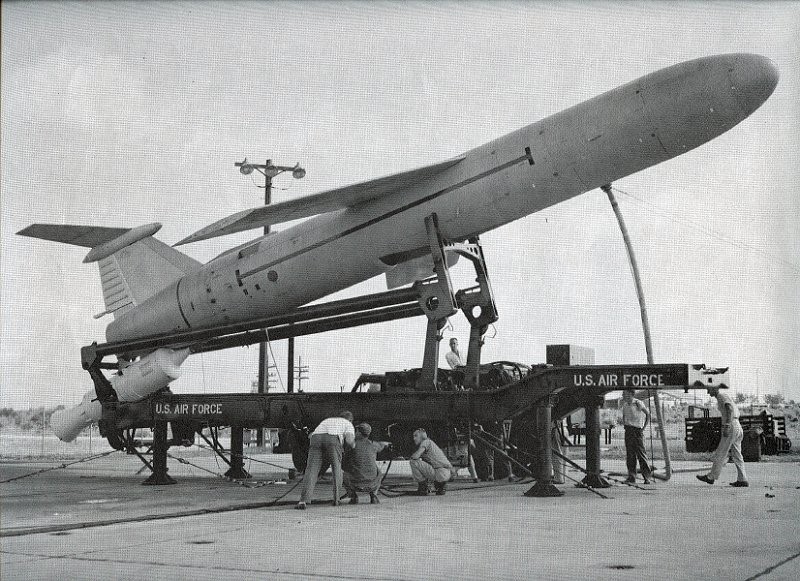

Eight “Martin Marietta Mace B” nuclear cruise missiles were deployed at that time at the Yomitan missile site, called “Site One Bolo Point” by U.S. military personnel. Bordne, who currently lives in Blakeslee, Pennsylvania, was one of seven crew members there.

There were a total of four Mace B sites in Okinawa including Bolo Point. Each site had eight missiles which were commanded and controlled by the Missile Operations Center at Kadena.

The main daily mission of Bordne, one of the flight-control specialists called Mech2, was to maintain the ready-to-launch status of Mace B missiles. Normally, once they started an eight-hour shift at the site, they “recycled” a missile, meaning powering down a missile, checking parts of the warhead, nosecone and flight control systems and returning it to ready-to-launch status.

“Oh, my God!” Bordne recalled his colleagues as saying as they turned white with shock and surprise when they received a launch order before dawn on Oct. 28. The order was issued from Kadena to all four Mace B sites in Okinawa including Bolo Point, he said.

According to him, the three-level confirmation process was taken step-by-step in accordance with a manual by comparing codes in the launch order and codes given to his crew team in advance. All of the codes matched.

“So, we read the targets out loud. Out of the four missiles, we had only one headed toward Russia. The other three were not going to Russia. That, right away, gave us a start to wonder. Because the launch directive said you launch all the missiles,”

Bordne said. His crew team was in charge of four out of eight missiles deployed at the site.

“And we figured, ‘Why hit these other countries?’ They’ve got nothing to do with this. That doesn’t make any sense,” Bordne said. “So, our captain, the launch officer, said to us ‘We’ve got to think this through in a logical, rational manner’.”

When the launch order was issued, the five-level “DEFCON” scale, or defense condition, remained at level 2, one step from starting a war. Theoretically, a launch order should not be issued unless DEFCON is raised to 1, which means initiating a military counterattack against enemy forces.

The order under DEFCON 2 made the crew team, especially the launch officer, so dubious about its authenticity that the officer ordered suspension of the ongoing launch procedures which Bordne was engaged in.

Finally, the launch officer figured out that the order had been mistakenly issued, Bordne said, but added he has no idea why such an order was issued. Even though Bordne did not specify which country had been targeted besides Russia under the order, it is believed to be China considering the Mace B missile range of 2,200-2,300 kilometers.

It is not clear what caused such a wrong launch order to be issued, but a U.S. U-2 spy plane was shot down over Cuba just a few hours before the order was conveyed to the Mace B sites in Okinawa.

Other former U.S. veterans in Okinawa recalled tense moments during the Cuban Missile Crisis in interviews with Kyodo News, even though they did not have direct knowledge about the aborted nuclear missile launch order, which seems to have been handled as a military secret.

“I knew I was never going home. If we had launched our missiles and they had launched their missiles, there would be nothing to go back to,” Bill Horn, a 71-year old former colleague of Bordne, recalled of the moment when he listened to the presidential address on Oct. 22, 1962, which made public the Soviet buildup of a missile base in Cuba.

“Everybody in that part of the Air Force, or in the military service, knew at that point in time that peacetime would be over, that there would be no more wars to fight…1962 was the closest we ever came to complete annihilation of civilization as we know,”

said Horn, who lives in Cookeville in Tennessee.

On Oct. 24, two days after the presidential address, the U.S. Strategic Air Command, the command unit at the time of a nuclear war, raised the “DEFCON” level from 3 to 2 without consultation with Kennedy.

“Going to DEFCON 2 was disturbing since DEFCON 1 is all-out war. DEFCON 2 is one step from war,” said Larry Havemann, another Mace B veteran who was stationed in Okinawa during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

“Since I was trained on the nuclear weapon I knew that if all the missiles were unleashed there would not be much left of this world or the people on it. That haunts me to this day,”

Havemann, 73, told Kyodo News in Sparks, Nevada.

After DEFCON 2 was issued, U.S. forces took a posture to be ready for war within 15 minutes.

The crisis ended on Oct. 28, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev announced that he would withdraw nuclear missiles from Cuba.

Ota Masakatsu’s report appeared at Kyodo News on March 27, 2015. The original report is available here.