Queen Elizabeth II: The Middle East She Knew in 1952

When the late monarch took the throne, Britain was still an empire and arguably the strongest power in the region. Since then, kings have fallen and new states arisen

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

When the late Queen Elizabeth II took the throne in February 1952, the UK was still an empire that held control over vast swathes of the planet and counted hundreds of millions of subjects.

Since then the world has seen wars, revolutions and coups. Britain’s empire has largely disappeared.

Much of the Middle East and North Africa, still a region where the UK holds deep ties – not least through the monarchy – was largely under British control, both directly and indirectly, when she came to the throne.

Cyprus, Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Yemen’s south, Oman and Sudan were all de jure or de facto ruled by the British Empire, while Egypt, Jordan, Iraq and Saudi Arabia were heavily under the empire’s influence.

The Middle East and North Africa in 1952

Much of the traditional control the UK exerted over the Middle East was grounded in a range of monarchies that had been imposed or backed by the empire and maintained close links to Britain’s royal family.

Elizabeth ascended to the British throne on 6 February 1952. At that time, Britain directly controlled most of what are now the Gulf Arab states, with only Saudi Arabia and North Yemen as independent states – albeit ones closely aligned to the empire.

Kuwait would have to wait until 1963 before it became formally independent, while the UAE (then known as the Trucial States), Qatar and Oman would remain protectorates until the 1970s.

Iraq, Iran, Egypt and Jordan were all monarchies aligned with Britain, while the Republic of Turkey would join the Nato alliance that year and come into the Western sphere of influence.

In 1955, Iraq, Iran and Turkey would join Pakistan and the UK in the anti-communist Baghdad Pact.

Four years before Elizabeth became queen, Britain pulled out of Palestine, but not before encouraging Jewish immigration and the Zionist movement’s plan to settle there – a policy that rocked a region that is still coming to terms with the creation of Israel.

Though Britain had left Palestine, in the wake of the Second World War the Middle East was firmly in the Western camp – though the fear of communism and Arab nationalism was never far from rulers’ minds.

Though no longer a direct colony, Egypt played a crucial role in the empire.

Under the rule of King Farouk, the country was closely aligned with Britain, the former colonial power. Poverty and inequality were rife in the kingdom under Farouk, but British support ensured – for a time at least – his administration’s ability to weather the burst of discontent from the populace.

The British had also shared sovereignty over Sudan with Egypt since 1899, maintaining forces in the southern region following their victory in the Mahdist war of 1881-1899.

Crucially, British forces were stationed around the Suez Canal, a route integral to international trade.

Constructed by the Suez Canal Company between 1859 and 1869, the British- and French-owned canal would later become symbolic for Egyptian nationalists of their country’s subservience to foreign powers.

Ensuring the steady flow of ocean trade was one of the key goals of the British Empire in the Middle East.

At the other end of the Red Sea was Aden, in the southwest of the Arabian Peninsula. The city’s port was one of the busiest harbours in the world for trade and travel in the 1950s, overlooking the Gulf of Aden.

Tens of thousands of British soldiers were stationed in Aden. Deals with local tribal leaders helped keep down threats from labour unions and leftists who demanded autonomy and better treatment for native workers – at least for the time being.

In addition to the forces stationed at Suez, control of the canal and Aden left the British fully in control of the quickest shipping route between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean.

At the time of her accession, Elizabeth counted more than 7,300,000 subjects in the MENA region, while a further 55,000,000 at least were under British influence.

A question of sovereignty

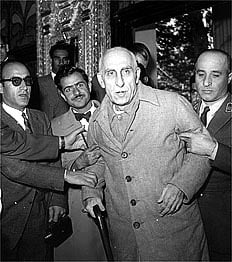

The Iranian government led by Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who in 1951 had nationalised his country’s oil industry, provided real concern for the empire.

Mosaddegh’s decision to take over the British-0wned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company – with the popular support of the communists – was in part motivated by the belief that the company existed as a means of exerting foreign control over Iran.

The takeover alarmed Britain and its allies. But the problem would be rectified soon: a year later, with the backing of the UK and the US, Mosaddegh would be overthrown in a coup and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi would be placed in full control of the country and in full deference to foreign powers.

Across the rest of the Middle East and North Africa, other colonial powers still held sway, as well.

Following the infamous Sykes-Picot agreement during World War 1, Syria and Lebanon had fallen under French control but had achieved independence by the 1940s.

However, Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria were still under French colonial rule, while Spain controlled what is now known as Western Sahara.

It would not be long before all demanded their own indepdence, with Algeria plunging in a brutal anti-colonial conflict, while Western Sahara remains a disputed region and site of anti-colonial struggle to this day.

The status quo was not to last.

Just five months after Elizabeth ascended to the throne, a group of nationalist military officials, including Gamal Abdel Nasser, launched a coup d’etat in Egypt, abolished the monarchy and declared the country a republic.

That event, perhaps more than any other, kicked off the process ending Britain’s role as the dominant power in the Middle East. Nasser’s government would later oversee indepedence and the end of UK rule in Sudan in 1956, as well as expelling British forces from Suez and nationalising the canal.

The Suez Crisis that followed would see Britain – and its allies France and Israel – fail to unseat Nasser through military force and re-assert control over the canal. The British Empire’s status as the foremost imperial power was over and the US would soon move in to take its place.

“We feel that we are strong, we feel that the world has changed,” Nasser said in a speech following the start of the invasion.

“They want to insult us? Well, we can also insult them… can’t our papers also insult the Queen and their prime minister?”

What the young queen thought – if anything – of these events goes unnoted, as became standard for a figurehead keen to be seen as apolitical.

The same year as the Suez Crisis, King Faisal II of Iraq would pay a visit to London.

In footage taken by British Pathe, Elizabeth, her husband Prince Phillip and other royals and government officials meet Faisal off the train at Victoria Station before being taken by a coach and horses down the thronged street to Buckingham Palace.

During the visit Elizabeth described Iraq as the “model of a modern state built on ancient and famous foundations and confidently facing towards the future”.

Within two years, Faisal would be overthrown and killed in a nationalist takeover inspired by Nasser’s coup in Egypt. The country would be declared a republic and withdrawn from the Baghdad Pact, growing closer to the Soviet Union.

By the end of the 1970s the only remaining monarchy outside of the Gulf was Jordan, with South Yemen becoming a “socialist country” after independence in 1967 (later uniting with the north in 1990), and Iran’s transformation into the Islamic Republic following the 1979 revolution.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Featured image: Mohammad Mosaddegh in court, 8 November 1953 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)