An Overview of the Asia-Pacific War 80 Years Ago, Japan Headed for Total Defeat

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Eight decades ago, the Asia-Pacific War officially began on the morning of Sunday 7 December 1941, with Japan’s military attack on the American-controlled Pearl Harbor naval base at Oahu, Hawaii. This region is located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, 2,400 miles away from the nearest point of the United States mainland coast, at San Francisco, California.

In Western historical annals, Japan’s raid on the Pearl Harbor base is often regarded as an attack on American soil itself, neglecting to mention that the US, for no just cause, had occupied and annexed Hawaii in the late 19th century. Russia has a much greater claim to the Crimea, which is historically Russian, than America ever had to Hawaii or Cuba, etc.

In a matter of minutes the Japanese aerial bombing of Pearl Harbor had wiped out the US Pacific Fleet stationed there. This gave Japan naval dominance in the Pacific Ocean, for the time being. Japan’s warplanes had failed to destroy the huge oil tanks in the dockyard, while Pearl Harbor’s installations like its submarine pens and signals intelligence units were undamaged; most importantly, the three US aircraft carriers (Lexington, Enterprise and Saratoga) were by chance out to sea at the time of the Japanese assault. By far the closest of the three was the Enterprise, which at dawn on 7 December 1941 was positioned around 215 miles west of Pearl Harbor.

Japan’s military leaders were, on the whole, contented indeed with the damage inflicted on the US Armed Forces at Pearl Harbor, which was greater than Tokyo had expected. In south-east Asia, a few hours before the bombing of Pearl Harbor even started, the Japanese 25th Army, led by Japan’s formidable commander Tomoyuki Yamashita, landed in northern British Malaya in the early hours of 7 December 1941. Mark E. Stille, a retired US Navy commander, wrote that “Of all the armies fielded by Japan during the war, the 25th Army was the best led and equipped”. By evening of the first day of the Japanese amphibious landings, the whole of northern British Malaya had been lost by the British, almost without a fight.

In the latter part of December 1941, the Japanese 25th Army successfully pushed down the Malayan peninsula coastlines, and the British withdrew before them. Having advanced over 200 miles southward, on 11 January 1942 General Yamashita’s divisions captured the Malayan capital city, Kuala Lumpur. By late January 1942 the British had retreated into Singapore island slightly further south, meaning that in 7 weeks the Japanese had cleared the entire Malayan mainland of enemy soldiers.

On 8 February 1942, an amphibious assault established the Japanese 25th Army on Singapore, considered a jewel in the British Empire’s crown. Despite General Yamashita’s troops being outnumbered, his men captured Singapore a week later on 15 February. More than 80,000 troops fell into Japanese hands, which on paper ranks as the largest capitulation in the history of British arms. Japan’s capture of Singapore signalled the end for the British Empire in the Eastern hemisphere.

British forces surrender Singapore to the Japanese, February 1942 (Licensed under the public domain)

Four hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor finished, the Japanese 14th Army (commanded by Lieutenant-General Masaharu Homma) assailed the Philippines in south-east Asia, a US colony since the late 19th century. On 10 December 1941 Japanese soldiers landed at Luzon, the Philippines’ biggest and most populous island in the north of the country. On that same day, 10 December, the Japanese 55th Infantry Division (Major-General Tomitaro Horii) captured from the Americans the Pacific island of Guam, located almost 1,500 miles to the east of the Philippines. Another 1,500 miles further east again in the Pacific a US territorial possession, Wake Island, was captured by Japanese marines on 23 December 1941.

The decorated American general, Douglas MacArthur, was commander of US Army Forces in the Far East. He was foiled in his plan to defeat the Japanese on the beaches of the Philippines. General MacArthur decided to abandon Manila, the Philippines’ capital city, and to retire not far west to another part of the country called the Bataan peninsula. Manila, now an open city, was taken by the Japanese on 2 January 1942.

Japan’s assault on Bataan had already started on 29 December 1941, but was repulsed by MacArthur’s troops with heavy losses for the attackers. Over the next 5 weeks, the Japanese could make no progress against the American and Filipino soldiers; their offensive was postponed in early February 1942. However, towards the end of February president Franklin Roosevelt in Washington ordered MacArthur to leave the Philippines, so that the general could assume command of fresh American forces being prepared in Australia.

On 11 March 1942, MacArthur reluctantly left the Philippines by motor torpedo boat and he had vowed, “I shall return”. MacArthur was much criticised at home, and by the American troops he had left behind in the Philippines, for having abandoned them; but to be fair to MacArthur on this occasion, there was little point in his remaining in the Philippines, and he could hardly disobey for long a direct order from president Roosevelt.

By now, Roosevelt had decided there was no possibility of relieving Bataan, and Japan’s hierarchy reinforced the Bataan area with 2 more Japanese divisions. On 3 April 1942, a new Japanese offensive in Bataan succeeded. Six days later on 9 April 1942, the US Major-General, Edward P. King Jr., chose to surrender along with 12,000 American troops and more than 60,000 Filipino troops.

While Filipino soldiers bore the brunt of the calamity in the northern Philippines, and subsequently the brutal Bataan Death March, the Battle of Bataan ranks as the largest overseas surrender of forces in American history; and the biggest surrender of US troops since September 1862 in the American Civil War, when 12,419 Union soldiers gave themselves up to the Confederates during the Battle of Harpers Ferry. After Bataan, complete defeat for US-led divisions was a matter of time in the Philippines, and on 8 May 1942 the country came under Japan’s total control.

Surrender of US forces at Corregidor, Philippines, May 1942 (Licensed under the public domain)

On 16 December 1941 Borneo, Asia’s largest island and positioned fewer than 1,000 miles south of the Philippines, was attacked by Japanese units consisting primarily of the 35th Infantry Brigade (Major-General Kiyotake Kawaguchi). The British-led forces managed to hold out in Borneo’s jungle-covered mountains until 1 April 1942, when they surrendered on that date.

Further north, Hong Kong, in south-eastern China, a British possession from the days of London’s narcotrafficking wars, was assailed by Japan on the morning of 8 December 1941, led by the Japanese 23rd Army (Lieutenant-General Takashi Sakai). During the Battle of Hong Kong, the Japanese advanced rapidly and captured at least 10,000 Allied troops. On Christmas Day 1941 Mark Aitchison Young, the British Governor of Hong Kong, surrendered in person to Lieutenant-General Sakai.

Concurrently with Japan’s campaign in British Malaya, about 1,000 miles to the north the Japanese began a large-scale assault to capture Burma (Myanmar), a south-east Asian state bigger than France which since 1824 had been under British rule. On 16 January 1942 the Japanese 15th Army, under the command of Lieutenant-General Shojiro Iida, cut into Lower Burma from neighbouring Thailand; the latter country, which until then was never colonised, had capitulated to the Japanese on 8 December 1941, and 2 weeks later Thailand signed a formal alliance with Japan.

On 31 January 1942, the Japanese captured the southern Burmese city of Moulmein from the British. Japan’s forces were enjoying significant help from Burma’s inhabitants, who strongly desired independence for their country. Much of the Burmese population were amazed to see Asian troops (the Japanese) outperforming white soldiers, and because of this the locals received a lot of encouragement. A myth had persisted in colonised nations that the white man was invincible.

The British withdrew from Lower Burma in February 1942. On 8 March 1942 the Japanese captured Rangoon, the capital city of Burma. Two days later on 10 March, the Japanese 55th Infantry Division started pursuing the departing British from Rangoon. These setbacks for the Allies in Burma caused a serious rupture in British-Australian relations. The Australian government had resisted great pressure from British prime minister Winston Churchill, who wanted the Australians to divert to Rangoon one of its two divisions that was returning from the Middle East, for the defence of Australia itself.

The Japanese had also gained a foothold in the petroleum-rich Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), which for decades was among the world’s biggest oil producing countries. The Dutch East Indies was designated by Tokyo as a vital target. Japan’s conquest of the Dutch East Indies was swift, as they advanced through its islands of Sumatra, Java and Celebes in late January, February and early March 1942. The Dutch East Indies’ capital city, Batavia (Jakarta), was taken by the Japanese on 5 March 1942. The Netherlands sued for peace 4 days later.

By the end of March 1942, Japan’s military had achieved each of its pre-war goals as outlined shortly before the attack on Pearl Harbor. After less than 4 months of fighting against the Western Allies, the Japanese had captured Hong Kong, British Malaya and Singapore, Thailand, Borneo, the Dutch East Indies, Guam and Wake Island, along with Rabaul on the island of New Britain in Papua New Guinea.

All of this was accomplished with just 11 Japanese divisions, quite clearly a remarkable feat of arms, equal to that of the 1940 German defeat of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark and Norway. Unlike with Germany, Japan has seldom been given credit in the West for its military triumphs, and the Japanese have generally been treated with contempt; which one can only assume, at this stage, is due at least in part to a lingering racism.

By March 1942 Japan’s forces, as highlighted earlier, had also firmly established themselves in the Philippines and in Burma. The above Japanese victories had come on top of their other recent conquests, such as taking an enormous swathe of eastern China by 1939, which altogether brought about 170 million Chinese under Japan’s rule; along with Tokyo’s capture by mid-1941 of all of French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia).

Britain’s colonial authorities believed that “all Japanese soldiers were very short-sighted and inherently inferior to western troops”, military author Antony Beevor wrote. Ordinary British soldiers on the frontline were better acquainted with the reality, and less likely to hold racist views. Almost 30 years after the war Gilbert Collins, a gunner in the British 14th Army, said that “The Japanese was a good soldier. He was a good soldier. When he was told to do a job, he would stop there until he died”. Captain Neville G. Hogan of the British 14th Army described the Japanese as “great fighting soldiers. Their battle drill was fantastic, you couldn’t help but admire them”.

Crucially, Japan’s troops had adapted very well to jungle warfare. Teruo Okada, an officer in the Japanese 15th Army recalled, “I liked the jungle, and it did not have the fear it seems to have had for some of the Allied soldiers. It was a friendly place, dark, where you could cover yourself and camouflage yourself. In the jungle, fortunately, the Burmese jungle, there are many bamboo groves, you see, and in Japan we all eat bamboo shoots, so that there is a lot of natural food in the form of bamboo shoots all over the place. Apart from that, we all know that what a monkey can eat, we can eat too. So if you watch the monkeys and avoid what the monkeys also avoid, you are fairly safe. There are such creatures as bandicoots, snakes, jungle lizards and tokays, small lizards, you cut off the head and chop them up and make it into curry. Mixed with pepper it can make a good curry”.

Freddie Tomkins, a sergeant in the British 14th Army, remembered how “I’d never seen a jungle, I’d seen a forest, but I hadn’t seen a jungle. We went in there, it was dark, dirty, damp, rain, all sorts of animal noises we never heard before. In actual fact it was really scary. We have our meats and our Yorkshire puddings and so forth. They [Japanese troops] lived on rice. Now you can’t get meat and Yorkshire pudding and greens and potatoes out there. So we had to reorganise ourselves and lived on the things that the army could produce for us. Like corned beef, and it’s the only place [Burmese jungle] that I know where you can open up a tin of corned beef and pour it out like a liquid”.

The Japanese, in early April 1942, captured from the Australians the Papua New Guinean islands of Buka and Bougainville, located not too far north of Queensland. Japan was attempting here to cut off Australia from American aid. That same month, in April, the Royal Navy had to abandon the Indian Ocean. Everything seemed to be going Japan’s way.

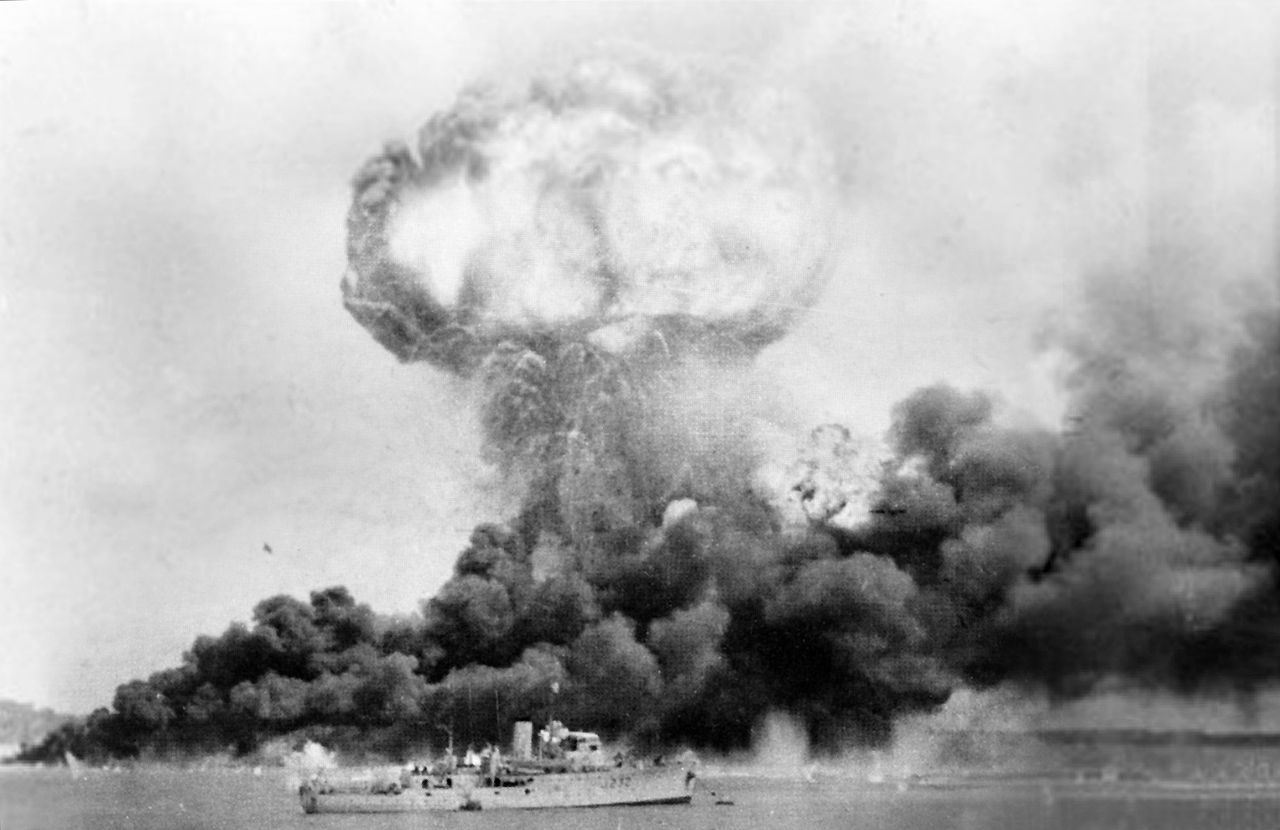

The Bombing of Darwin, Australia, 19 February 1942 (Licensed under the public domain)

By April 1942 the Japanese leadership had a decision to make. To rest on its gains, or to ambitiously extend the area of Japan’s supremacy through more military conquests. They chose the latter option. Tokyo decided to neutralise Australia and Hawaii, by targeting those areas with land-based Japanese bomber aircraft.

Also in April 1942, the new perimeter of the Empire of Japan was enlarged on maps by Tokyo’s strategic planners – in order to include the capture of the Aleutian Islands (North Pacific), Midway (North Pacific), Samoa (south-central Pacific), the Fiji Islands (South Pacific), New Caledonia (south-western Pacific) and Port Moresby (south-western Pacific).

Elsewhere, in south-east Asia the Japanese advance northwards through Burma was continuing. The British commander, Harold Alexander, was forced to retreat with his soldiers to the town of Prome in central Burma. General Alexander was unable to hold on to Prome, which was taken by Japan’s soldiers on 2 April 1942. Just over 2 weeks later, on 18 April Japanese forces had advanced 115 miles north of Prome to capture the city of Yenangyaung, on the famous Irrawaddy River, Burma’s largest river. The final remnants of Britain’s troops withdrawing from Yenangyaung destroyed the city’s power station, so as to prevent its use by the enemy.

On the following day, 19 April 1942, the Japanese 55th Infantry Division took the town of Pyinmana, 95 miles east of Yenangyaung. The day after that, Japan’s troops captured the city of Taunggyi, 140 miles east of Yenangyaung. On 22 April, the British decided to fall back to Meiktila, a city located on the Meiktila Lake.

On 25 April 1942 the Anglo-American commanders in Burma, Harold Alexander, William Slim and Joseph Stilwell, decided to pull all Allied troops out of the country. Nearly a week later, on 1 May the Japanese 18th Infantry Division captured Mandalay, Burma’s 2nd biggest city, while they also cut the Burma Road. The following week, on 8 May the Japanese took the city of Myitkyina in northern Burma.

By mid-May 1942, British-led forces had retreated out of Burma north-westwards to neighbouring India, where they found refuge in the city of Imphal. Military historian Donald J. Goodspeed wrote, “The rains then came and brought another disastrous campaigning season to a close. British casualties in Burma had been about three times higher than the Japanese loss of forty-five thousand men”.

To the east in the North Pacific Ocean thousands of miles away, a greater catastrophe was to unfold for Japan during the Battle of Midway (4–7 June 1942). Their defeat in this engagement, against the Americans, saw Japan’s military lose 4 of their aircraft carriers, 1 heavy cruiser, 275 planes along with the deaths of 3,500 men, including many experienced pilots. In spite of their past victories and huge territorial expansion, Japan’s reverse in the Battle of Midway made certain their utter defeat in World War II. The American admiral Chester W. Nimitz said, “Midway was the most crucial battle of the Pacific War, the engagement that made everything else possible”.

The Americans were assisted in their defeat of the Japanese at Midway, by their having previously cracked Tokyo’s codes. English historian Andrew Roberts wrote, “Intelligence was key to the American victory at Midway, both the accurate and timely information that Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander-in-Chief in the Pacific, was given by his code-breakers, and the halting and inaccurate reports that Admirals [Isoroku] Yamamoto and [Chuichi] Nagumo got from their intelligence officers, who did not have the luxury of reading their enemy’s signals”.

How had it come to this for the Japanese? The fact is that a bloody conflict had ensued in the Eastern hemisphere between two imperial powers, America and Japan, for control over sections of the globe, and Japan would ultimately lose. America had boasted the world’s largest economy since 1871, and was becoming richer as the decades passed. The US was a significantly wealthier and stronger nation than Japan, possessing greater industrial power and manpower.

In 1941 the US was easily the planet’s largest oil producing country. That year the Americans manufactured more than 5 times more oil than the Soviet Union in 2nd place. By the end of World War II, the Americans had in total built an incredible 296,000 aircraft, 86,333 tanks and 952 warships. The German-Axis armies had invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 with 4,400 warplanes and 4,000 tanks.

On 26 July 1941, in response to Japan’s occupation of southern French Indochina, the Roosevelt administration froze all Japanese assets in America, and instituted an oil embargo against Tokyo. Drastic actions like this by Roosevelt’s government, which were the driving force behind the Asia-Pacific War erupting, immediately resulted in 90% of Japan’s oil imports being wiped out along with 75% of its foreign trade. These were grave issues for a resource-poor nation like Japan. Their oil supply could last only until the end of January 1943; that is, unless Japan’s forces embarked upon more military adventures.

By November 1941, a month before Pearl Harbor, the American demands on Japan had become so severe that, according to US historian and analyst Noam Chomsky, “Japan would have had to abandon totally its attempt to secure ‘special interests’ of the sort possessed by the United States and Britain, in the areas under their domination, as well as its alliance with the Axis powers, becoming a mere ‘subcontractor’ in the emerging American world system. Japan chose war – as we now know, with no expectation of victory over the United States but in the hope ‘that the Americans, confronted by a German victory in Europe and weary of war in the Pacific, would agree to a negotiated peace in which Japan would be recognized as the dominant power in Eastern Asia’.”

Japan’s foreign policy was undoubtedly expansionist, up to a point. There was no Japanese presence at all in the Western hemisphere or the Middle East, nor would it have been tolerated by the Americans short of war. Much more serious from Japan’s viewpoint, Washington was not prepared either to grant Japan hegemony within its own spheres of interest in east Asia. Summarising Tokyo’s predicament, the Japanese Foreign Affairs Minister Yosuke Matsuoka asked, “Is it for the United States, which rules over the Western hemisphere and is expanding over the Atlantic and Pacific, to say that these ideals, these ambitions of Japan are wrong?”

President Roosevelt from the outset of World War II was “aiming at United States hegemony in the postwar world”, historian Geoffrey Warner wrote. After 1939, top-level US State Department officials highlighted which regions of the globe the US would control, titled by Washington planners as the Grand Area. In the early 1940s, the Grand Area of US hegemony was designated to consist of the entire Western hemisphere, the Far East (at the expense of Japan) along with the former British Empire, which contained the Middle East’s oil and gas reserves. England was to be assigned a junior partner role subordinate to the American boss, a status which has held true ever since.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree. He is interested in writing primarily on foreign affairs, having been inspired by authors like Noam Chomsky. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Sources

Naval History and Heritage Command, “Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941, Carrier Locations”, 1 April 2015

Mark E. Stille, Malaya and Singapore 1941–42: The fall of Britain’s empire in the East (Osprey Publishing; Illustrated edition, 20 Oct. 2016)

Peter Chen, “Invasion of Burma”, World War II Database, October 2006

Antony Beevor, The Second World War (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2012)

Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars (Random House Value Publishing, 2nd edition, 3 April 1985)

Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War: A New History of the Second World War (Harper, 17 May 2011)

Noam Chomsky, On The Backgrounds of the Pacific War, Liberation, September-October 1967, Chomsky.info

The World At War: Complete TV Series (Episode 14, Fremantle, 25 April 2005, Original Network: ITV, Original Release: 31 October 1973 – 8 May 1974)

Evan Mawdsley, Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War, 1941-1945 (Hodder Arnold, 23 Feb. 2007)

Oil production by country, 1900 – 2018, Youtube.com

Featured image: USS Arizona burned for two days after being hit by a Japanese bomb in the attack on Pearl Harbor. (Licensed under the public domain)