|

In the context of the revolution that erupted in Germany as the country suffered defeat in November 1918, a revolutionary situation also arose in Strasbourg, capital of Alsace, a province that still belonged to the Reich at that time.

Inspired by the proclamation of a “free and socialist republic” in Berlin by Karl Liebknecht on the 9th of that month — and the proclamation, on November 8, of a Bavarian soviet republic (Räterepublik) in Munich, mutinous soldiers as well as civilians seeking radical political and social changes, mostly workers, established a Russian-style revolutionary council or “soviet” in the Alsatian capital and immediately introduced all sorts of radical democratic reforms, including abolition of censorship, wage increases, improved working conditions, the right to strike and to demonstrate, etc.

In addition, the revolutionaries declared that they wanted “nothing to do with the capitalist states” and desired to be neither German nor French but aspired to be able to live, thanks to the “triumph of the red flag,” in a “Republic of Alsace-Lorraine” (Republik Elsaß-Lothringen) that would be free, democratic and linguistically tolerant. A red flag fluttered from the lofty spire of the Alsatian capital, but the democratic project launched there resonated throughout the province: revolutionary movements simultaneously emerged in many other towns of the province, including Colmar, Mulhouse, Haguenau, Molsheim, Neuf-Brisach, Ribeauvillé, Saverne, and Sélestat. Red flags also appeared in the city of Metz, major city of the northern part of Alsace’s neighbouring province, Lorraine, likewise still part of the German Reich in 1918, though not for much longer.

In Strasbourg, the local bourgeoisie, overwhelmingly German-speaking, as well as the local social-democratic leaders, were horrified and decided that they preferred to be “French rather than red.” They appealed to the French army to “rush to Strasbourg as soon as possible” in order to put and end to “red rule” in the city. French troops entered Strasbourg a few days earlier than planned, namely on November 22, overthrew the soviet and cancelled all the democratic measures it had fathered. Strasbourg and the rest of Alsace (and the north of Lorraine) were unilaterally and unceremoniously annexed by France and subjected to a draconian process of “re-francisation”, including a prohibition of the use of the German and even Alsatian languages in education and in the public administration, the demotion of persons of insufficiently French origin to the status of second-class citizens, and the expulsion or ostracism of anyone suspected of disloyalty to France; the famous Doctor Albert Schweitzer was one of the victims of this sort of treatment. After their “liberation”, the Alsatians were less free than before and were no longer allowed to speak their own language, and many of them were (mis)treated as aliens in their own land.

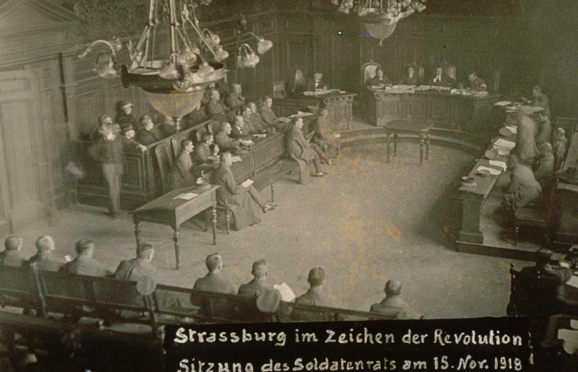

Meeting of the Strasbourg soviet on November 15, 1918(Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg 686107, CC BY 2.0, c/o Wikimedia Commons)

The case of Alsace illustrates the sad fact that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the Great War was not a “war for democracy” at all. Even the arguably most democratic of all belligerent powers, France, clearly did not fight for ideals such as democracy, justice, and the Wilsonian principles of self-determination; its victory represented the triumph of a fanatical and intolerant version of nationalism, a consolidation of authoritarian rule, and a setback for democracy.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Jacques R. Pauwels is historian and political scientist, author of ‘The Myth of the Good War: America in the Second World War’ (James Lorimer, Toronto, 2002). His book is published in different languages: in English, Dutch, German, Spanish, Italian and French. Together with personalities like Ramsey Clark, Michael Parenti, William Blum, Robert Weil, Michel Collon, Peter Franssen and many others… he signed “The International Appeal against US-War”.

Featured image: Proclamation of the republic in Strasbourg on November 10, 1918 (Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg 686071, c/o Wikimedia Commons)

|