|

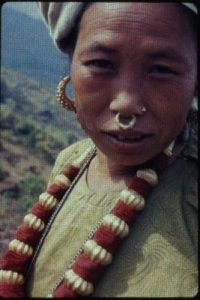

Featured image: Nepal Limbu worker

Aama disappears into the darkened house to light the fire. Flames ignite from hot coals stirred out of the ash and Aama eases a pot of kodo onto the rock grill. Neither an announcement nor a spoken invitation is needed. We rise from our workplaces and move inside, seating ourselves around the hearth. Danamaya takes a ladle, stirs the brew, and pours a spoon of the steaming liquor in each brass bowl set on the ground in front of us.

Mylie follows laying small leaf plates on the ground near our bowls, then places on each plate a back, spicy sauce. I recognize this, a sharp lemony pickle– a typical popular Limbu achar that accompanies every Nepali’s meal whether we’re eating rice or vegetables or drinking liquor. Some of the workers prefer kodo; others choose raxsi, also warmed to taste.

‘I’m surprised”, I remark. “My friend Monamaya isn’t with us. She promised to help with my naugiri.”

“Monamaya will arrive soon”, murmurs Danamaya, adding “when the raxsi is warmed.”

Just then Monamaya struts into the room and seats herself beside me, gleefully accepting an immodest portion of raxsi from Aama and turning to me says, “Ah, Didi; so you’ll have your very own Limbu jewels; eh eh.” She leans closer, lifts my cigarette from my hand and holds its glowing tip to light her own.

“What a day! A sheep got loose so sisters and I spent the whole morning searching for it,” complains this unapologetic latecomer. Everyone takes a sip of their drink without comment.

Limbu Danamaya In my presence people withhold their opinion of Monamaya. They know she and I have become friends since my arrival here and they seem to respect our closeness. Monamaya is the only unmarried woman her age that I know in Kobek. She’s the most audaciously raucous and bold, even by Limbu standards. I recognize that she’s a social oddity. She doesn’t like to work in the fields, behavior which in this rural community is interpreted as irresponsible. Like me, she doesn’t feel the need for a companion when traveling through the hills. If she needs to go to town, she fearlessly sets out alone on the three-hour walk. I was never able to discover the reason for my friend’s unpopularity and I was left to enjoy her companionship as I pleased.

After everyone has consumed at least three bowls of kodo, we return to the veranda where we’ll stay until our task is complete, now joined by Monamaya. The alcohol seems not to have reduced anyone’s capacity for the delicate work.

“Kodo and raxsi are nourishment for us,” explains my friend. “Without it we can’t work at all; drinking this we don’t need any other food.”

Our workforce is augmented by two newcomers, elderly women from Salaka lineage, thus clanswomen of my host. Buddhamaya is a tall, dry-witted lady with aristocratic features set in a heavily wrinkled face. We adjust our seating to make space for Buddhamaya on the mat; Danamaya hands her a nylon thread to which she replies, “Who is this for?”

“White Didi here,” explains my host.

“Why do you want this?” the old woman demands of me. “This is for poor farmers. You should have solid gold pieces– here, here, here,” she shouts, stroking me to indicate just where gold might encase my head and arms–like some Limbu-Aztec warrior princess. (Ugh, the thought is itself an encumbrance.)

Monamaya comes to my defense.

“No, no. white Didi is going to wear this to the Chatrapati feast next week; then she’ll take it with her to America. Everyone there will admire it. And Didi will tell Americans all about our poor land.”

I remain silent. I have already passed hours fruitlessly arguing with my hosts about my devotion to their lifestyles. I’ve had no success explaining how this necklace is an example of their art, or their beauty. They insist that my interest is only curiosity, and this naugiri will be presented outside as a curio, and will stimulate discussion of Nepal’s economy, an economy they expect to be viewed as poverty.

It’s probably true that I’m interested in the naugiri for what it might (or might not) represent about the economy here. I’ve never understood how an average hill farmer affords jewelry like the naugiri and the gold earrings, items which seem extravagant to me, yet which, while essential, are not a sign of wealth. A naugiri is the price of a valued plowing bullock. While every woman wears a naugiri, fewer than ten percent of households possess a pair of oxen.

Certainly one can’t equate the cost of this necklace to the price of an ox. A naugiri is not in the same class as animals or land. Land is highly valued and people work hard to save to buy land and prepare new paddy fields. A naugiri is hard to put a cash price on. It’s an obligatory expense for a family, like a wedding or funerary feast—an integral part of family social and economic obligations.

A Limbu naugiri embodies a whole set of sentiments which I cannot possibly untangle, identify and comprehend. It’s not a dowry. It does not in itself mark one’s marital status. My naugiri it does not reflect a personal indulgence in ornamentation. I myself wear no bangles, bracelets or earrings. (My neighbors had already noted this, with some dismay.) Nevertheless these Limbu companions really want me to take this piece of jewelry with me when I depart. Curio or art, it is a gift to me wrapped in their memories. It symbolizes our bond and the cooperative spirit of our months together.

My Limbu naugiri As for myself? Why am I determined to have a naugiri? Well, from when I first set eyes on one, it symbolized the vigor or Limbu womanhood. I like its combination of a coarse, chunky, undazzling weightiness, and its dull gold luster. It may not be refined, but it’s nevertheless beautiful, somehow more precious because every woman owns one. It’s not for special occasions but an everyday thing she carries on her chest– as she suckles her baby, stirs pots of kodo and rice, cleans the hearth and sweeps the yard, and plants potato or millet. It’s a well made object requiring intense labor and constructed to last a lifetime.

Where is my naugiri today? Well, it seemed so precious that I made it a wedding gift to the young woman who married my son. Sadly, they divorced after only two years and I’ve lost track of both her and the necklace. I wonder what Danamaya or even Monamaya would think of its fate.

Originally published on Heresies, A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, Jan/Feb, 1978.

All images in this article are from the author.

|