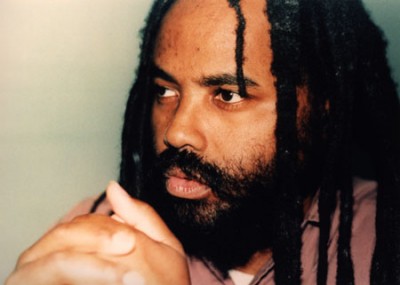

Mumia Abu-Jamal Remains the Voice of the Voiceless

After 40 years of incarceration the “voice of the voiceless” remains a focus of international attention

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

During the late 1960s, Mumia Abu-Jamal became a youth activist in the city of Philadelphia where a succession of racist police chiefs engaged in widespread abuse against the African American community.

Philadelphia has a centuries-long history of African self-organization dating back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries when the Free African Society, African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) and other institutions were formed by Richard Allen, Sarah Allen and Absalom Jones.

During mid-19th century, the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society provided avenues for men and women to build support for the Underground Railroad and the movement to completely eradicate involuntary servitude in the antebellum border and deep southern states. By the 1960s, the city became known as one of the first municipalities where African Americans would rise up in rebellion on the north side during the late August 1964.

Max Stanford (later known as Muhammad Ahmed), a co-founder of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) in 1962, was from Philadelphia. RAM proceeded the Black Panther Party (BPP) and sought to form an alliance with Malcolm X (also known as El Hajj Malik Shabazz), a leading spokesman for the Nation of Islam and later the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). RAM advocated for the development of a revolutionary movement in the U.S. and consequently became a target of the Justice Department.

In 1969, Mumia joined the Black Panther Party at the age of 15 when the organization was deemed by the then Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) J. Edgar Hoover as the “greatest threat to national security” in the United States. The Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) had a special division which was designed to monitor, disrupt, imprison and kill various leaders and members of African American organizations from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the BPP as well as a host of other tendencies. Documents released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) since the mid-to-late 1970s indicate that the BPP was a principal target of the U.S. government and local police agencies.

Why was the BPP considered so dangerous by the leading law-enforcement agency inside the country? In order to provide answers to this question it must be remembered that between 1955 and 1970, the African American people led a struggle for civil rights and self-determination which impacted broad segments of the population in the U.S. helping to spawn movements within other oppressed communities.

The Black Panther Party was first formed in Lowndes County Alabama in 1965. Its origins grew out of the organizing work of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), whose field organizer, Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) was deployed to the area in the aftermath of the Selma to Montgomery march in late March of the same year. Working in conjunction with local activists, an independent political party was formed known as the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). The group utilized the black panther as its symbol while rejecting both the Republican and Democratic Party.

In subsequent months, there were other Black Panther organizations formed in several cities including Detroit, Cleveland, New York City and other urban areas. In Oakland, California during October of 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.

This movement represented an emerging phase of the Black liberation struggle where there were calls for armed self-defense, mass rebellion and the political takeovers of major municipalities by those who had been excluded from the reins of official power. Thousands of African American youth flocked to the Black Panther Party viewing the organization as a symbol of uncompromising resistance to racism, national oppression and economic exploitation.

Mumia and the BPP

Although the BPP was projected in the national corporate media as gun toting militants willing to use weapons against the police when they were threatening the Party and the community, most of the work of the organization revolved around distribution of its weekly newspaper, the establishment of free breakfast programs for children, community health clinics for the people in the most oppressed areas of the African American community while building alliances with revolutionary forces among other sectors of the population including, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Asians, Native Americans and whites committed to fundamental change within U.S. society.

Mumia noted the diversity of programmatic work during his tenure in the BPP of the late 1960s and early 1970s in his book entitled “We Want Freedom”:

“As the Breakfast program succeeded so did the Party, and its popularity fueled our growth across the country. Along with the growth of the Party came an increase in the number of community programs undertaken by the Party. By 1971, the Party had embarked on ten distinctive community programs, described by Newton as survival programs. What did he mean by this term? We called them survival programs pending revolution. They were designed to help the people survive until their consciousness is raised, which is only the first step in the revolution to produce a new America.… During a flood the raft is a life-saving device, but it is only a means of getting to higher ground. So, too, with survival programs, which are emergency services. In themselves they do not change social conditions, but they are life-saving vehicles until conditions change.” See this.

On December 4, 1969, the Chicago police under the aegis of the Illinois State’s Attorney Edward V. Hanrahan and the Chicago field office of the FBI, raided the residence of BPP members on the city’s west side. Two Panther leaders, Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were killed while several other occupants of the house were wounded.

These police actions along with hundreds of other attacks on BPP chapters across the country resulted in the deaths of many Panther members and the arrests and framing of hundreds of cadres. Numerous BPP members were driven into exile as others were sentenced to long terms of imprisonment.

The Voice of the Voiceless from the Streets to Death Row

On December 9, 1981, Mumia was arrested in Philadelphia and charged with the murder of white police officer Daniel Faulkner. He was railroaded through the courts and convicted on July 3, 1982. The following year, Mumia was sentenced to die by capital punishment. He remained on death row until 2011 after an international campaign to save his life proved successful.

However, his death sentence was commuted to life in prison without parole. Mumia and his supporters have maintained that he is not guilty of the crime of killing a police officer.

After his sojourn in the BPP, Mumia utilized his writing and journalist skills learned in the Party to become a formidable media personality in Philadelphia. He was a fierce critic of police brutality and a defender of the revolutionary MOVE organization which emerged during the 1970s in the city.

Mumia was a co-founder of the Philadelphia chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) in the 1970s. He worked as a radio broadcaster and writer exposing the misconduct of the police surrounding the attack on the MOVE residence in August 1978. In 1979, he interviewed reggae superstar Bob Marley when he visited Philadelphia for a concert performance.

While behind bars Mumia has become an even more prolific writer and broadcast journalist. He issues weekly commentaries through Prison Radio where he discusses a myriad of topics including African American history, international affairs, political economy, the deplorable conditions existing among the more than two million people incarcerated in the U.S. along with police misconduct. (See this)

A renewed campaign entitled “Love Not Phear” held demonstrations around the U.S. and the world during the weekend of July 3 marking the 40th anniversary of his unjust conviction in 1982. Love Not Phear says that it is committed to the liberation of all political prisoners including Mumia Abu-Jamal.

An entry on their website emphasizes that:

“The landscape has changed over the last 40 years, a time frame that also marks the years Mumia has been incarcerated. The fight for the release of political prisoners requires a recalibration in order to challenge police corruption and racism as they have evolved in this new landscape. We cannot deny the racism, corruption, and misconduct that permeated the so-called ‘Halls of Justice’ during Mumia’s arrest and unjust kangaroo court trial. The people today know the truth; commonplace bribed witnesses, suppressed evidence, biased judges, and backroom deals put Mumia behind bars.” (See this)

Mumia through his attorneys have filed another appeal based upon evidence related to prosecutorial misconduct which has been further revealed over the last four years. The hearing will take place on October 19 in Philadelphia. Supporters of Mumia and other political prisoners will attend the hearing in this latest attempt to win the long-awaited freedom for this activist who is now 68 years old.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Abayomi Azikiwe is the editor of the Pan-African News Wire. He is a regular contributor to Global Research.