|

Note: This article was revised on April 9, 2018 to add some additional material and to correct some inadvertent errors in the previous version.

Few people understand the Canadian government’s relationship with the Bank of Canada or the nature of the Bank’s original raison d’être. Back in 2011 a lawsuit had been filed in the Federal Court by the Committee on Monetary and Economic Reform against the Government of Canada and the Bank of Canada. The lawsuit attempted to:

[R]estore the use of the Bank of Canada to its original purpose, by exercising its public statutory duty and responsibility. That purpose includes making interest-free loans to the municipal/provincial/federal governments for ‘human capital’ expenditures (education, health, other social services) and/or infrastructure expenditures.

After nearly five and a half years of contentious litigation, after five court hearings resulting in contrary decisions, on May 4, 2017 the Supreme Court of Canada declined to hear the appeal case, in “deference” to the political process, i.e., their decision was that the matter appeared to be more of a political issue than a judicial one. However, strong arguments can be made to the contrary and further court procedures may still take place. But in the meantime, since it appears that the issue at present cannot be resolved through a judicial process, there is now an urgent need to deal with this in the political arena.

The Bank of Canada was established in 1934 under private ownership but in 1938 the government nationalized the bank so since then it has been publicly owned. It was mandated to lend not only to the federal government but to provinces as well. To help bring Canada out of the Great Depression debt-free money was injected into various infrastructure projects. With the outbreak of World War II, it was the Bank of Canada that financed the enormously costly war effort – Canada created the world’s third largest navy and ranked fourth in production of allied war materiel. Afterwards, the Bank financed programs to assist WW2 veterans with vocational and university training and subsidized farmland.

For the next 30 years following World War II, it was the Bank of Canada that helped to transform Canada’s economy and lift the standards of living for Canadians. It was the Bank that financed a wide range of infrastructure projects and other ventures. This included the construction of the Trans-Canada highway, the St. Lawrence Seaway, airports, subway systems, and financial assistance to a corporation that placed Canada in the forefront of aviation technology – a project that was scuttled and destroyed by a controversial federal government decision. In addition, during this period seniors’ pensions, family allowances, and Medicare were established, as well as nation-wide hospitals, universities, and research facilities.

The critical point is that between 1939 and 1974 the federal government borrowed extensively from its own central bank. That made its debt effectively interest-free, since the government owned the bank and got the benefit of any interest. As such Canada emerged from World War II and from all the extensive infrastructure and other expenditures with very little debt. But following 1974 came a dramatic change.

In 1974 the Bank for International Settlements (the bank of central bankers) formed the Basel Committee to ostensibly establish global monetary and financial stability. Canada, i.e., the Pierre Trudeau Liberals, joined in the deliberations. The Basel Committee’s solution to the “stagflation” problem of that time was to encourage governments to borrow from private banks, that charged interest, and end the practice of borrowing interest-free from their own publicly owned banks. Their argument was that publicly owned banks inflate the money supply and prices, whereas chartered banks supposedly only recycle pre-existing money. What they purposefully suppressed was that private banks create the money they lend just as public banks do. And as banking specialist Ellen Brown states: “The difference is simply that a publicly-owned bank returns the interest to the government and the community, while a privately-owned bank siphons the interest into its capital account, to be reinvested at further interest, progressively drawing money out of the productive economy.” The effect of such a change would remove a powerful economic tool from the hands of democratic governments and give such control to a cabal of foreign bankers. This was one of Milton Friedman’s radical free-market ideas.

At that time it seems that Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau came under the influence of neoliberalism, promulgated by Frederich Hayek and Milton Friedman. Then, while attending the Basil Committee sessions, he probably came under further influence of fellow Bilderberg attendees and as a result he accepted the partisan flawed logic from the world’s top banks. Apparently on the basis of this, he decided that Canada should dramatically reduce borrowing interest-free money from Canada’s own bank and instead borrow the bulk of its money from chartered banks and pay interest on the loans. It appears that this decision was made without informing Canada’s parliament. This was such a fundamental change of policy that it should not only have been debated in parliament, this should have been put to a national referendum. Strangely, even when this became known, this was apparently never questioned by the opposition parties, especially the NDP, and never revealed in the media. Strange indeed.

Since the Coyne affair in the early 60s, the long-standing debate about the autonomy of the Bank of Canada from so-called government control has been ignored. Central banks around the world are supposed to be autonomous, concerned only with monetary policy while the governments are to be concerned with fiscal policy. What many elected representatives do not realize is that fiscal policy and monetary policy interact with each other and can supplement each other. This is acknowledged in the Bank of Canada Act where the Governor of the Bank of Canada and the Finance Minister must consult regularly with each other.

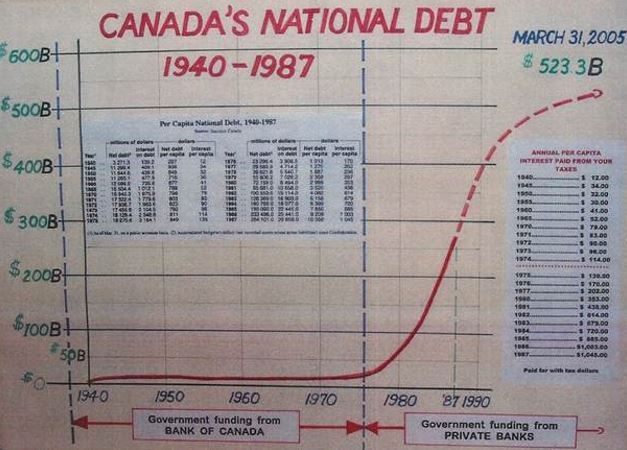

Successive Canadian governments have surrendered sovereign control over monetary policies and money supply to the beliefs of the international neoliberal private bankers and investors. As a result, Canadians have been saddled with government debt at all levels – debt that has risen exponentially since 1974. During the time that the Bank of Canada provided additional money, interest-free, to federal and provincial governments when it was needed, according to data supplied by Jack Biddell (accountant with Clarkson-Gordon, the first commissioner on the federal anti-inflationary board representing the province of Ontario and the chairman of the Ontario Inflation Restraint Board), the federal debt remained very low, relatively flat, and quite sustainable during all those years. (See his chart below.) In fact, in 1974 the country’s debt totalled only 18 billion dollars. When Canada stopped relying on its own bank it launched the country on a staggering deficit accumulation path. In 2016/17 the combined federal and provincial debt was $1.4 trillion, of which the federal debt was $728 billion. It appears that perhaps as much as 90% of the $1.4 trillion is the result of compound interest charges created by investors and private banks.

A history of Canada’s debt, using or not using the Bank of Canada. Source: Jack Biddell

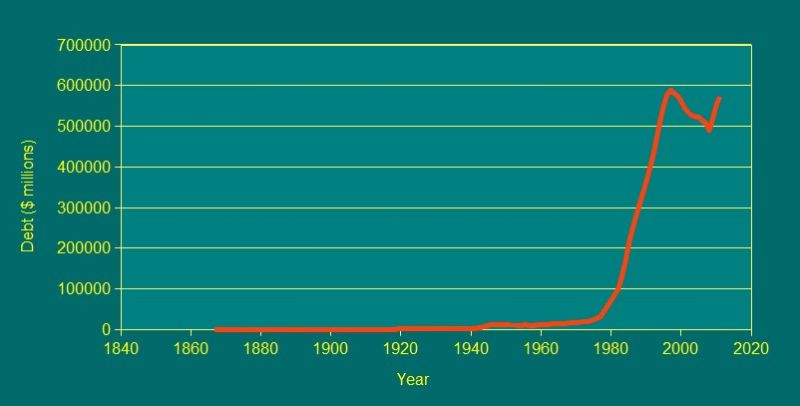

Canada’s net federal government financial debt from confederation to 2011. Source: Statistics Canada, Table 385-0010

The above chart illustrates the history of Canada’s federal debt; obviously something went terribly wrong after 1974. Over a 108-year period (1867-1974) the accumulated debt shows as nearly a flat line growing to only $18 billion. But around 1974, the debt began to grow exponentially and, over a mere 43 years, it reached to $728 billion in 2017.

The debt curve that began its exponential rise in 1974 tilted toward the vertical in 1981, when interest rates were raised by the U.S. Federal Reserve to 20%. At 20% compounded annually, debt doubles in less than four years. Canadian rates went as high as 22% during that period. Canada has now paid over a trillion dollars in interest on its federal and provincial debt—at least more than twice the actual debt itself.

A further example of this is that in the early 1990s, at the height of the media’s deficit hysteria and the demand to cut social programs, 91 per cent of the $423-billion debt at that time was due to interest charges. As revealed by an Auditor-General’s report to parliament (section 5.41), our real debt – revenue minus expenditures – was just $37 billion.

In other words, from 1867 to 1992 the federal government accumulated a net debt of $423 billion. Of this, $37 billion is the actual debt, which represents the accumulated shortfall in meeting the cost of government programs since 1867. The remainder, $386 billion, represents the amount the government has borrowed to service the debt, essentially a payment of interest on interest to the private sector. If the government had borrowed, interest-free, from the Bank of Canada to service the actual shortfall of $37 billion, a debt to private sector and banks of $386 billion would have never been created.

Although other points could still be presented, or some matters debated, the essence of this issue has been made clear. What now remains are a series of questions that need answers.

Why did both the Conservative and Liberal federal governments oppose the lawsuit in Federal Court that would have obliged the government to resume borrowing the bulk of extra needed money, interest-free, from the Bank of Canada? Why did these governments oppose this? Was this opposition to the lawsuit based on an agreement that may have been made by Prime Minister Trudeau in 1974 with Bank for International Settlements to henceforth reduce borrowing at no interest from the Bank of Canada?

Why did the Bank of Canada oppose the lawsuit that would have required the government to borrow the bulk of its extra needed money from the Bank of Canada interest-free as mandated under the Bank of Canada Act?

After its meeting with the international bankers’ Basel Committee in 1974, the federal government proceeded to borrow the bulk of its needed money, with interest charges, from private investors including banks and dramatically reduced dealing with its own bank that had no interest charges. This was done in secret and without the approval of parliament. Once this dereliction of duty to parliament and Canada’s people became known, why didn’t the opposition parties, especially the NDP, complain and make a major issue of this matter?

Why is it that Canada’s mainstream media has never brought any of these matters to the public’s attention? After the Supreme Court declined to deal with this case, citing specious reasoning that this was more of political issue than a judicial one, the media boycotted the story and therefore hardly anyone in Canada knows of this case. Canada’s top constitutional lawyer Rocco Galati who handled this lawsuit has always gotten major media attention, except for this case, which he considers to have been his most important lawsuit. Prior to this, Galati had been best known for stopping the Supreme Court appointment of Judge Marc Nadon, whose nomination had been put forward by Stephen Harper. Although Galati is unable to identify his sources, he states that he was informed that the government instructed the mainstream media to give this case, and prior lawsuits on this matter, limited coverage. And they complied. The story trickled out through alternative news sources.

In the course of five court hearings dealing with this case, Rocco Galati, as the lead lawyer, maintained that since Canada joined the Bank of International Settlements all their ensuing meetings have been kept secret. Their minutes, discussions and deliberations are secret and not available nor accountable to Canada’s Parliament, notwithstanding that the Bank of Canada policies emanate directly from these meetings. As Galati has stated:

“These organizations are essentially private, foreign entities controlling Canada’s banking system and socio-economic policies.”

As such, private foreign banks and financial interests, contrary to the Bank of Canada Act, dictate the Bank of Canada and Canada’s monetary and financial policy.

It was hoped that these court hearings would have led to civil proceedings on behalf of Canadians, to reveal matters and make them crystal clear to the public and politicians, but the mainstream media have effectively ignored these proceedings and have never revealed any of this vitally important information to the Canadian public. Why?

If the federal government needs additional funds to those collected by taxes, it should borrow ALL these funds from its own bank, basically interest-free. This is especially important since cutting out interest has been shown to reduce the average cost of public projects by about 40%. Why should the government be borrowing from private investors and chartered banks whose rapacious compound interest charges then result in horrendous federal debt? It’s not that this is something novel and unheard of. The state of North Dakota has had a state-owned bank for almost a hundred years, the Bank of North Dakota – the only such bank in the USA, although it should be noted that many other US jurisdictions are now looking at this option. The BND holds all of the state’s revenues as deposits by law. As Ellen Brown has stated:

The BND is able to make 2% loans to North Dakota communities for local infrastructure — half or less the rate paid by local governments in other states. For example, in 2016 it extended a $200,000 letter of credit to the State Water Commission at 1.75% … Since 50% of the cost of infrastructure is financing, the state can cut infrastructure costs nearly in half by financing through its own bank, which can return the interest to the state… .The profits return to the bank, which either distributes them as dividends to the state or uses them to build up its capital base in order to expand its loan portfolio.

In the case of China where the government owns most of the country’s banks, China has managed to fund massive infrastructure projects all across their country, including 12,000 miles of high-speed rail built just in the last decade. These state-owned banks return their profits to the government, making the loans interest-free; and the loans can be rolled over indefinitely. If China can do this, why can’t Canada with its own Bank of Canada?

If North Dakota can have a publicly owned bank, why can’t each of Canada’s provinces have their own banks? It appears that because of Canada’s constitution, current laws and regulations, this at present is not possible – until appropriate amendments are made.

Alberta in the 1930s attempted to establish a publicly owned bank but this was blocked by the federal government. Instead, the province then formed the Alberta Treasury Branch in 1938. Although this is technically not a bank, it provides virtually every service that a bank can do. In 2015 it had assets of $43 billion and provided financial services to about 700,000 Albertans in 243 communities. Hence this still continues to play a vital role in the province.

In 1975 the NDP government in British Columbia set out to establish a ‘super bank,’ but to avoid problems with the federal Bank Act, this was called the B.C. Savings & Trust. The NDP government was defeated in the next election and nothing came of this endeavour.

Ontario used to have the Province of Ontario Savings Office (POSO) and during the Rae years, one MPP, Jim Wiseman, chair of the first finance committee, attempted to persuade the provincial finance minister, Floyd Laughren, to fund the provincial deficits through the POSO. His efforts were unsuccessful and in the next election the government was defeated, and there was never a public debate on this matter. The governments of Harris and McGuinty sold POSO to the private sector, as part of their neoliberal “age of austerity.”

Ed Schreyer, while premier of Manitoba from 1969 to 1977, was thwarted in his efforts to form a publicly owned bank or a treasury branch; he continues to support the idea that the federal government should obtain its loans, interest-free, for infrastructure purposes from the Bank of Canada.

As it stands, profits from chartered banks can be siphoned into offshore tax havens, but with publicly owned banks, in addition to providing interest-free loans, profits would be recycled to the government and thereby to Canadian society.

Although resolutions calling for a return to government borrowing from the Bank of Canada instead of the private banks have been passed at NDP conventions, it does not appear that the NDP has ever pursued this matter in Parliament. Why is this? This is a fundamentally important question. Has this been the result of lack of sufficient information or has there been some other reason? The NDP should pose the questions I have raised in this article in Parliament, and demand answers.

Since the Supreme Court has refused to hear the case, contending that this is more of a political issue than a judicial one, and before the case is pursued further in the courts, surely it behooves the NDP to pursue this matter. Not just pursue it, the NDP should make this a cause célèbre! Although the NDP is now in a distinct minority in Parliament, they should nevertheless pose questions to the government about its position on this critically important matter. Let the government try to defend its position, which in many ways is untenable and certainly not in the best interests of the Canadian public. The media would then have no choice but to reveal this to the public.

In any case, this issue should become a major plank in the NDP platform. If properly and fully pursued it could be of great help in getting support from the electorate. As it stands, it seems that the international banking cabal appears to have such a grip on Canada’s current capitalist government that it has refused to act in Canada’s best interests. As in the case of getting Medicare enacted in Canada, it may be up to a social democratic party to eventually get the Bank of Canada reinstated as the country’s bank.

*

John Ryan, Ph.D., is a retired professor of geography and a senior scholar at the University of Winnipeg.

|