Manchester Bomber Was a UK Ally

Part 1 of Declassified UK’s investigation into the Manchester Bombing

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Salman Abedi and his closest family were part of Libyan militias benefitting from British covert military support six years before he murdered 22 people at the Manchester Arena in 2017. He is likely to have been radicalised by his experience.

The Manchester bomber and his closest family were part of Islamist militia forces covertly supported by the British military and Nato in the Libyan war of 2011.

The UK facilitated the flow of arms to Libyan rebel militias at the time, and helped train them, in a programme outsourced to its close ally, the Gulf regime of Qatar.

One of Salman Abedi’s close friends, Abdalraouf Abdallah, who was later convicted in the UK for terrorism offences related to Syria, fought in the 2011 Libyan war for the main militia group the UK helped to take over the Libyan capital.

Abdallah told the Manchester Arena inquiry he was trained by Nato at the time – a claim Nato denies.

Salman Abedi and his brothers Ismail and Hashem may have received training from militant groups that British special forces were working with to overthrow Muammar Gaddafi’s Libyan regime.

Evidence points to the Manchester bomber being radicalised by his experience in the UK-supported war in Libya in 2011. Aged 16 at the time, it was the beginning of the road that led to him murdering 22 innocent people at the Ariana Grande pop concert six years later.

Martyrs and Revolutionaries

Muammar Gaddafi’s regime had been in power since 1969 and when an ‘Arab Spring’ uprising began in February 2011, a variety of militia groups were formed to overthrow him.

Dozens of men from the British-Libyan community in Manchester flocked to the country to join the fight. They were of varying political convictions, from nationalist to jihadist.

Irrespective of their ideologies, Libyan militia forces were backed by Nato, which launched thousands of air strikes beginning in March 2011 against Gaddafi’s forces. The military intervention, which was led by the UK, France and the US, was backed across the British media and parliament.

The Manchester bombing inquiry heard that the Abedi family was associated with the February 17th Martyrs Brigade and the Tripoli Revolutionary Brigade, the latter which focused on seizing the Libyan capital, Tripoli. There was considerable fluidity of personnel between the militias.

The inquiry, which finished hearing testimonies in March and will report later this year, also heard evidence from the Greater Manchester Police (GMP) that Salman Abedi either fought with the Martyrs Brigade during the 2011 war or attended a training camp or both.

A police raid on a house a few months before the bombing found 65 photographs taken during the Libyan war apparently showing Salman and and his younger brother Hashem in camouflage uniforms, holding weapons, and with an insignia on the wall behind of the Martyrs Brigade.

Hashem was convicted in 2020 of helping his brother plan the bombing and sentenced to 55 years in jail.

The Facebook account of Salman’s older brother Ismail also contained an image of him holding a rifle with the Martyrs Brigade flags behind him and other images with him in camouflage clothing holding a rocket-propelled grenade launcher and a machine gun.

The father

The inquiry was also told that Salman’s father Ramadan Abedi, who had a long history of opposition to the Gaddafi regime and of association with Islamist extremists in the UK, was part of the Martyrs Brigade and the Tripoli Brigade.

Ramadan took Salman and Hashem to the Libyan capital in August 2011 to aid the rebels. This was just as the militia forces were descending on Tripoli.

Police told the inquiry that Ramadan’s sister Rabaa informed them he had returned to fight the regime and that he received a shrapnel wound in his back which stopped him fighting on the front line.

A fellow fighter in Libya, Akram Ramadan, said he fought with Ramadan as part of the ‘Manchester Fighters’ and that he saw Ramadan “in the mountains and later in Tripoli”.

It remains unclear if Salman fought in Libya. His friend Abdalraouf Abdallah told the inquiry he didn’t see him fighting on the front line but “probably he did fight”.

A cousin of the Abedi brothers said that, following the downfall of the Gaddafi regime, Salman obtained a job locating Gaddafi supporters.

Covert support

UK military forces on the ground, working with Nato, covertly supported the Libyan militias and directly aided the Tripoli Brigade’s takeover of the capital.

In answer to a parliamentary question, the UK government said in March 2018 it “likely” had contacts with the Martyrs Brigade in the 2011 war. But Whitehall has, unsurprisingly, never publicised its support for the Islamist forces.

Britain had dozens of special forces in Libya calling in air strikes and helping rebel units assault cities still in the hands of pro-Gaddafi forces.

But Whitehall went further, secretly training rebel groups in advance of the attack on Tripoli. SAS operatives advised rebels on tactics as they prepared to storm the capital.

The Tripoli Brigade was the main rebel force that eventually took over the capital in late August 2011. In its ranks fought both Abdalraouf Abdallah and his brother Mohammed, who was also later convicted of terrorism in the UK for joining Islamic State in Syria.

The Telegraph reported at the time that British and French intelligence officers played a key role in planning the final rebel assault on Tripoli.

UK special forces reportedly “infiltrated Tripoli and planted radio equipment to help target air strikes” and “carried out some of the most important on-the-ground missions by allied forces before the fall of Tripoli”, US and allied officials told Reuters.

This was part of a broader plan involving Nato and Qatari forces which took months of planning, and involved secretly arming rebel units inside the capital.

Those units helped Nato destroy strategic targets in the city, such as military barracks and police stations, as they attacked the capital from all sides.

The Ministry of Defence refused Declassified’s freedom of information request asking for records it holds on the Tripoli Brigade. It said it could “neither confirm nor deny” it held such information.

‘Rebel air force’

A rebel planning committee, which included the Tripoli Brigade, drew up a list of dozens of sites for Nato to target in the days leading up to their attack on the capital.

The Tripoli Brigade-led military advance came amid an increased number of sorties and bombings by Nato aircraft. British Tornado fighter planes destroyed targets such as an intelligence communications facility concealed in a building in southwest Tripoli and government-controlled tanks and artillery.

Husam Najjair, a sub-commander in the Tripoli Brigade, wrote in his memoir after the war of Nato “backing us up from the air” as his forces attacked Gaddafi’s powerful Khamis Brigade, named after his youngest son.

Nato jets also struck targets around the Gaddafi leadership compound at Bab al-Aziziya, which was taken by the Tripoli Brigade, as Najjair documents in his book. The base was “bombed repeatedly by Nato”, he wrote.

A report by the global intelligence firm Stratfor, revealed by WikiLeaks, noted that Nato “served as the de facto rebel air force…during this push into Tripoli”.

It highlighted the seminal role played by Nato in the rebels’ success, stating that a “compelling rationale for the apparent breakthrough by rebel forces is an aggressive clandestine campaign by Nato member states’ special operations forces”.

This was “accompanied by deliberate information operations – efforts to shape perceptions of the conflict.”

Arming the militias

The UK may have directly armed the militias with which the Abedis were associated, and certainly helped to ensure they were armed.

A France24 film that followed the Tripoli Brigade’s seizure of the capital noted that Britain and France had given weapons to the unit. This was later denied by Husam Najjair, who appeared in the film.

As early as March 2011 the adviser to then US secretary of state Hillary Clinton, Sidney Blumenthal, informed her that French and British special forces were working out of bases in Egypt, along the Libyan border, and that “these troops are overseeing the transfer of weapons and supplies to the rebels”.

The SAS was operating closely with Qatari special forces which were delivering large quantities of arms to the militias such as Milan anti-tank missiles. A video posted on Youtube in May 2011 appeared to show the Martyrs Brigade testing Milans.

Overall the UK government was “using Qatar to bankroll the Libyan rebels”, the Times reported, since the militias lacked the firepower to win the war by themselves.

The Obama administration secretly gave its blessing to Qatari arms shipments in spring 2011 and soon began receiving reports that the supplies were going to Islamic militant groups.

Nato air and sea forces around Libya had to be alerted not to interdict the cargo planes and freighters transporting these arms into Libya.

Overall, Qatar is believed to have sent $400m in aid to the militias, involving huge quantities of arms. All the weapons supplies were illegal since they contravened an arms embargo, as a UN security council report of 2013 documented.

Qatar also later admitted deploying hundreds of its own troops to support the Libyan rebels. Its chief-of-staff, Major-General Hamad bin Ali al-Atiya, said the regime “supervised the rebels’ plans because they are civilians and did not have enough military experience”.

He also said: “We acted as the link between the rebels and Nato forces.”

But Qatar also helped train and equip the Tripoli Brigade specifically.

Training in the western mountains

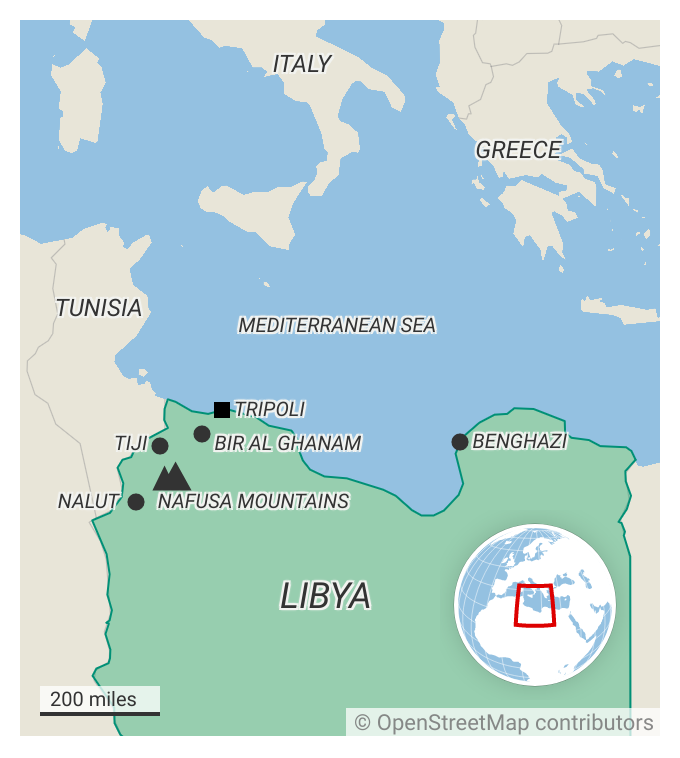

The militants in the Tripoli Brigade who successfully took the capital had swept through the country from the west, from their base at the town of Nalut in the Nafusa Mountains, about 280 kilometres from Tripoli.

The Brigade had been formed in late April in Benghazi by Mehdi al-Harati, an Irish-Libyan living in Dublin, and Husam Najjair, his brother-in-law, a 32-year-old building contractor also living in the Irish capital.

The Brigade received training from Qatari special forces in Nalut and is also reported to have flown some rebel commanders to the Gulf state for training.

Some reports have said Britain was involved in this secret training of opposition fighters in the Nafusa mountains, alongside Qatari and French forces.

Indeed, a Reuters investigation, quoting several allied and US officials, as well as a source close to the Libyan rebels, noted that Britain played a key role in organising this training.

It reported that British, French and Italian operatives, as well as representatives from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, began in May 2011 to organise serious efforts to hone the rebels into a more effective fighting force. Most of the training took place in the rebel-held western mountains.

Fighting with Nato

“We started from the border of Tunisia, called Jebel Nafusa”, Abdalraouf Abdallah told the Manchester bombing inquiry. He said he received training from Nato on “how to aim, shoot and reload”, and that he was “translating for Nato”.

“We were fighting and Nato fighting actually with us, or alongside with us, as the British Government also,” he added. “And then there was a big plan of how to take over Tripoli because that was the stronghold of Gaddafi”.

In his memoir Tripoli Brigade sub-commander Husam Najjair reveals that “three American Nato officials” visited the unit’s Nalut headquarters in the Nafusa mountains. “Having communication with Nato was very important to us, so we were happy to show them around”, he wrote.

“They made it clear they didn’t want media attention”, he added.

Najjair says he once acted as a translator between the Americans and two Libyan gun smugglers funnelling arms into Tripoli. This was “to give the Yanks as much information as possible about the coordinates of the latest loyalist military installations”.

Najjair also wrote that he met the Americans “to detail our plans for the advance and our military targets” as the brigade pushed towards Tripoli. He had a “walkie-talkie direct to Nato”, he quotes his commander, Mehdi al-Harati saying to him.

A Nato official told Declassified: “There were no forces under Nato command in Libya during the conflict in 2011. In line with its mandate from the UN Security Council, Nato’s mission in Libya consisted of policing the arms embargo, patrolling a no-fly zone, and protecting civilians from attack by Gadhafi forces.

The official added: “While it is a matter of public record that some Nato Allies had small military contingents on the ground in Libya, Nato was not involved in training opposition forces.”