Hybrid Wars in sub-Saharan Africa: The Strategic Position of Malawi and Zambia

Hybrid Wars 8

The landlocked countries of Malawi and Zambia are little-known to the rest of the world, yet they occupy very strategic positions in the continental interconnectivity projects and Hybrid War projections.

Zambia is situated smack dab in the center of north-south and east-west corridors, while Malawi – for all of its poverty and underdevelopment – is still located in a strategic space between the future gas giants of Tanzania and Mozambique and the forthcoming logistical powerhouse of Zambia. Due to Malawi and Zambia’s shared history as separate British colonies and even part of the same one under the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, as well as their neighborly and landlocked status, it’s appropriate to discuss both of them in the same chapter about Hybrid War.

Unlike many of the previous reviews that have been undertaken, this one will be comparatively shorter owing to the relative lack of detailed information about these countries, though that shouldn’t be taken to infer that they’re no less important than the other states that have been studied thus far. Malawi and Zambia may not presently be the center of regional focus, but continental connectivity trends indicate that they’ll play a much greater strategic role in the future, albeit for two different reasons. Zambia will be the pivotal transit location between intersecting transport corridors, while Malawi will always remain the vulnerable disruptor in Southern Africa that could risk spoiling the entire regional arrangement if its stability unravels. Should it remain mildly stable into the future, then it could reversely play the role of a geopolitical guarantor in preventing an outburst of Weapons of Mass Migration from derailing these multipolar projects.

The research will kick off by discussing Malawi’s position between Tanzania, Zambia, and Mozambique, before describing some of its domestic and historical factors that could one day be exploited to undermine its stability. Afterwards, the work will progress to talking about Zambia and the critical interconnector role it plays in bringing together north-south and east-west mobility projects in Africa. As with Malawi, Zambia is also vulnerable to a major destabilization scenario, though one which could deal even more damage than its neighbor’s and seriously curtail the transcontinental integration projects that are expected to pass through its bottleneck territory.

Giving Meaning To Malawi’s Geography

Regional Discrepancies:

Malawi might seem to many to just be a strip on the west coast of Lake Malawi/Nyasa (if they even knew where the country was to begin with), but it actually occupies an advantageous position at the crossroads of three very important states. Like was explained in the chapter introduction, Tanzania and Mozambique are two of the world’s most promising energy giants, while Zambia is the location of planned cross-continental logistics networks. Even though Malawi is not directly linked up with any of them, it’s still within close enough proximity that any humanitarian destabilization within the country could prompt a debilitating outflow of Weapons of Mass Migration that interfere with these said projects’ viability through the disruption of each host state’s domestic equilibrium.

Socio-economic challenges are expected to noticeably increase in this densely populated nation as it explodes from 16 million people to 43 million by 2050 and then 87 million by the turn of the next century. Its present southern-concentrated Muslim minority of an estimated 13% of the population will obviously grow in proportion to this and might even gain relative ground during the country’s demographic acceleration, which might encourage irresponsible rabble-rousing rhetoric about an impending “Clash of Civilizations” and all of the resultant conflict scenarios that go with it. Focusing more on this point at Malawi’s oncoming population boom, it’s absolutely uncertain how the country will remain sustainable even in its already deeply impoverished state, and it can’t be discounted that naturally occurring humanitarian problems might develop where famine or natural disasters lead to a massive exodus of Malawians to their neighbors. Depending upon the scenarios that unfold in the future, there might even be internal migrations between the Northern, Central, and Southern Regions if the population doesn’t outright leave the country in droves (or is unable to because the borders are blocked).

This might upset the balance between the three regions, which currently sees the capital of Lilongwe in the central one as the largest city, the southern hub of Blantyre as the country’s second-largest city, and the northern capital of Mzuzu as the third-largest in Malawi. It should be qualified at this point that the Central and Southern Regions are the most populous, and that in some ways the Northern one sits at the distant periphery of the nation’s importance. Furthermore, Blantyre is connected to Mozambique’s ports of Beira and Nacala (as will be described below), while the national capital of Lilongwe is thus dependent on its southern regional counterpart for accessing the trade that runs through these routes. This state of affairs makes Blantyre the country’s economic capital and Lilongwe its political-administrative one, and the rivalry between the two regions and their city centers might become a primary point of discord in the event of future humanitarian or political crises.

Mozambican Dependency:

Malawi isn’t strategic only because of its very real potential for a domestic meltdown, though that’s certainly a large part of why it’s of interest to foreign actors, whether to reinforce the stability of their regional projects by assisting the state or to gain an influencing upper hand in potentially destabilizing it and tangentially taking down the rest of its neighbors in the process. Approached from a positive and multipolar forward-looking angle, Malawi could also actively contribute to regional connectivity because of its advantageous location between these countries, but provided of course that this opportunity is identified and pursued by its partners.

The Shire River in the southern part of Malawi connects to the Zambezi and further along to Mozambique’s second-largest port of Beira, while international roads run adjacent to this path. Malawi’s other vector for international trade and general interaction with the outside world comes through the northeastern Mozambican port of Nacala, which is also linked with the country via roads. Both routes could also serve rail freight, but Mozambique’s domestic network was destroyed during the Civil War and is thus incapable of connecting to Malawi’s Central East African Railway system.

Nowadays Malawi is totally dependent on Mozambique’s transport corridors in every sense of the word, and its strategic vulnerability has spiked in the face of RENAMO’s recent offensives against the government there. Recalling the previous chapter about that country and the map that was included in the research, RENAMO lays claim to all of the territory through which Malawian goods must transit on their way to the rest of the world. This means that the non-state actor essentially has the opportunity to hold an entire state hostage if they decided to target their truckers or if the military situation in these provinces became so critical that most Malawian trade was halted as a result. In any case, Malawi’s dependence on trans-Mozambican infrastructure networks indirectly makes the country a member of the enlarged Indian Ocean economic community and thus gives these high seas paramount importance for Lilongwe in conducting its agriculturally dominated international trade.

Trouble With Tanzania:

Although its northern border is located very close to TAZARA, Malawi either doesn’t want to or is unable to take advantage of this because of the territorial trouble that it has with Tanzania. The two countries are engaged in a dispute over their international boundary on Lake Malawi/Nyasa. Lilongwe claims the entirety of the northeastern part of the body of water all the way up to the Tanzanian shoreline, while Dodoma says that the international boundary should be split evenly in the middle. This disagreement has become increasingly significant in recent years after oil deposits were prospected under the waterbed, meaning that whoever has control over its surface territory will reap the windfall of revenue that this results in. Malawi is much poorer than Tanzania and has a smaller population at only 16 million people, so forthcoming energy profits could possibly be put to more concentrated and effective use by Lilongwe than by Dodoma, though that’s not to say that Tanzania shouldn’t automatically be disentitled from some of the proceeds, too.

The issue is still being negotiated, though for the reason explained above, it’s difficult to see why Malawi would cede any of its claims or agree to respect any international arbitration that deprives it of its absolutist share over this potential cash cow. From the reverse perspective, much mightier Tanzania has every reason to continue pressing its claims, especially since the Chinese-financed Mtwara Development Corridor will turn Dodoma’s Lake Malawi/Nyasa shores into a new hub of business and thus heighten the periphery’s attractiveness to the national center. As both sides remain stubborn in their claims and international maritime tensions boil, there remains a distinct possibility that they could explode into armed conflict if one side or another engages in a provocation, which in this context, might most likely be staged by the Tanzanians since they have everything to gain and the Malawians have everything to lose if the two clash. It’s probably because of their simmering tensions that Malawi doesn’t see Tanzania as a reliable transit partner for diversifying its international trade routes from the Mozambican RENAMO-influenced ports of Beira and Nacala, so Lilongwe will likely continue to remain dependent on its eastern neighbor for the foreseeable future so long as the Tanzanian dispute remains unresolved.

The Zambian Detour Or Zambia’s Detour?:

The most hopeful opportunity that Malawi has for relieving its dependency on Mozambique is to expand its rail network to Zambia and onwards to one of the several crisscrossing infrastructure projects cutting through the country. The first step in this direction was already taken in 2010 with the commissioning of the Chipata-Mchinji railway between both states. It has thus far underperformed in its potential and most of Malawi’s trade is still conducted with Mozambique or by means of its territory through Beira and Nacala ports. Instead of the railway serving to diversify Malawi’s international trade away from Mozambique, it might reversely have the effect of deepening its dependency due to Zambia’s own grand strategy of infrastructural diversification.

Lusaka wants to position itself as the central crossroads of South-Central African trade, and in doing so, it has a vision to extend its own rail networks through Malawi and onwards to Nacala. The existing problem is that Mozambique’s relevant rail line to that port hasn’t been operational for decades, though this is why the African Development Bank approved a long-term $300 million loan in February for restoring the route. If the route is completed and RENAMO doesn’t behave as an obstructive force in inhibiting the corridor’s economic viability, then the ZaMM (Zambia-Malawi-Mozambique) railroad could function as a complementary Silk Road in pairing with the Tanzanian portion to Zambia and allowing for a secondary Indian Ocean terminal for the Southern Trans-African Route (STAR). This is because Nacala would link to TAZARA, which in turn could connect to Angola’s Benguela line via the Northwest Railway that might soon be constructed in Zambia.

ZaMM would be a welcome addition to multipolarity’s network of transnational infrastructure projects if it ever sees the light of day, though it would be entirely ironic for Malawi given that its plans for a Zambian detour away from Mozambique ultimately turned into Zambia’s own detour to Mozambique and Malawi’s double dependency on its neighbor.

Color Revolutions And Coups Along The Lake Malawi/Nyasa Coast

Demographic, “civilizational”, and intra-regional pressures present the most ‘organic’ conflict scenarios for Malawi, and like it was mentioned above, these could predictably lead to an outflow of Weapons of Mass Migration into the three surrounding states. That being said, there are also two much more artificially manufactured destabilization scenarios that could burst forth in Malawi at any moment, and these are Color Revolutions and coups, both of which have a recent history of attempted deployment in the country. The situational specifics of any future iteration of these schemes might change, but the general idea of foreign-supported regime change would remain the same.

Color Revolution Failure:

Malawi was rocked by a failed Color Revolution attempt in July 2011, though one which ultimately claimed a handful of lives and confirmed that the China-orienting country was on the list of America’s regime change targets. Prior to the events, President Bingu wa Mutharika had recognized Beijing as China’s official government in 2008, after which bilateral relations took off and the two started moving to one another. Chinese investments entered the country and Beijing’s influence was finally felt in one of the few corners of the world where it had been absent over the past several decades. Mutharika’s policy reversal towards China was significant because Malawi had previously been in full lockstep with Western policies ever since its 1964 independence and Cold War rule under President Hastings Banda. Malawi’s leader tried so hard to emulate the Western establishment that he sometimes even outdid his patrons, such as when his country – the only African one with diplomatic ties to apartheid South Africa – continued trading with Pretoria despite many of his European and American partners sanctioning it from 1986 until its removal in 1994. This is why Mutharika’s about-face caught so many off guard, since it totally broke with his predecessors’ stringent policy of recognizing Taiwan.

In the run-up to the Color Revolution, the government expelled the UK High Commissioner in April 2011 after he called the president “autocratic”, “combative”, and “intolerant of criticism” – smears that are regularly used in ginning up an information campaign against a foreign leader. It shouldn’t be too unexpected that a protest movement broke out a few months later in July, and following the government’s defensive actions in restoring law and order, the UK and the US both suspended their aid to the donor-dependent country as punishment for its president’s success in fending off the regime change operation. The suspicious timing between the UK’s implicit anti-government threats and the unleashing of a Color Revolution shortly thereafter is enough to make one question whether the entire mess was managed by Malawi’s former colonial occupier, just as the close coordination between London and Washington’s aid suspensions lend credence to the thought that the US might have had something to do with this as well. Mutharika didn’t directly accuse either of them for being behind the deadly commotion, but he did point his finger in early 2012 at what he claimed were some unnamed donor nations that were working with in-country NGOs to organize the protests against him.

‘Constitutional Coup’:

Mutharika suddenly passed away in April 2012 at the age of 78, sparking a brief constitutional crisis of who his legal successor should be. Per the constitution, power must be transferred from the President to the Vice-President during the passing of the former, though the tricky situation was that Mutharika had disowned his successor a year beforehand. Joyce Banda entered into problems with Mutharika and was dumped from the ruling party in 2010, just one year after he picked her to run on his winning ticket during the 2009 elections. Banda allegedly didn’t support Bingu’s plans to have his brother and then-Foreign Minister Peter Mutharika succeed him in the future, and this dispute is what led to her de-facto dismissal. The problem, however, was that Banda chose not to resign from her post and stubbornly remained the legal Vice-President throughout the rest of Bingu’s tenure. The ruling Democratic Progressive Party was factionalized by the controversy and Bingu did not have enough influence within his own party to get her impeached. Therefore, when he abruptly died in early April, she legally became his successor, though there was a short two-day period where the government met without her and conspired to pass the baton to Bingu’s brother, Peter. The plot didn’t succeed because the military wouldn’t stand behind it, and therefore Banda became Malawi’s first female president.

What’s interesting about this episode is that Banda didn’t even belong to the ruling party by that time, having been expelled in 2010. She created her own “People’s Party” in May 2011, just two months before the Color Revolution. This was obviously done in tactical coordination with the UK and US, which evidently threw their weight behind her as they tried to topple Mutharika. It’s telling that just a few months after Banda’s inauguration, the US rescinded its former aid suspension and renewed its donations to the country, clearly as a reward for their proxy’s victory during the ‘constitutional coup’. Even more curiously, the American-based and globally renowned Forbes magazine included Banda on their list of the world’s most powerful women from 2012-2014, with the latter year unbelievably ranking her as the 40th most powerful despite her never achieving anything of international significance ever in her career. It doesn’t take much to realize that this was just a more personal reward for the politician in exchange for returning Western influence to the country, even though she never ended up going as far as reversing her predecessor’s recognition of Beijing. In spite of her ‘popularity’ in Forbes and the ‘power’ that the Western elite said that she had, Banda dismally lost her first-ever election in 2014 and was replaced by Bingu’s brother, Peter Mutharika, thus preventing her from fully carrying out her envisioned/ordered policies.

Coup Fears:

Peter Mutharika’s presidency has been marked by a balance between Malawi’s traditional Western aid partners and China, though even this pragmatic approach towards Beijing appears to have set off alarm bells in the Western capitals. The investigation itself is still ongoing, but the government claims to have foiled a coup plot in February of this year. According to reports, the American Ambassador met with opposition leader Lazarus Chakwera during his visit to the US and hatcedh a coup plot, one which allegedly was also being organized with other conspirators through WhatsApp. The specific details of how the putschists planned to seize power haven’t been publicly released (at least to the author’s knowledge), so it’s unclear whether this was meant to be a military coup, a ‘constitutional coup’, or a Color Revolution coup. In what might be an unrelated event but which could also possibly have something to do with this scandal, the president dismissed the head of the army at the end of July. One media report said that this was because the country’s intelligence chief linked him to a planned coup, which if true, would confirm that the original plotters from February (the US and its on-the-ground network of political and NGO proxies) haven’t given up on their mission to overthrow Mutharika.

Just as it was with his brother Bingu, Peter Mutharika is being targeted because of his government’s decision to continue Lilongwe’s relationship with Beijing. Banda was unable to cut Malawi’s ties with China because they had simply become much too advantageous for her country, as was seen when she signed a $667 million electricity deal with China’s Export-Import Bank in 2013. It’s not known why she would do this while still being a stereotypical Western stooge, but it could be that she felt confident enough that the US and UK wouldn’t turn on her just for that, especially since they had already invested in helping her gain power in the first place. The fact that Banda would still continue Malawi’s relationship with China despite she herself being a Western proxy is a strong testimony to just how important China has become to the country in the less than a decade since bilateral ties have been established. Peter, for his part, went even further and recently hosted a China-Malawi Investment Forum where he invited China to take part in a wide array of projects in the agriculture, agro-processing, energy, mining, ICT, tourism, infrastructure, and manufacturing industries, among others. Pretty much, he offered to open the entire country up to Chinese capital in exchange for the development that it would bring, and with this in mind, it’s reasonable to predict that the last two pro-US coup plots certainly won’t be the last to be attempted.

Demystifying Zambia

With Malawi’s strategic situation and Hybrid War vulnerabilities out of the way, it’s now time to connect the research to neighboring Zambia, the mysterious-sounding country in South-Central Africa which the casual observers knows absolutely nothing about. To give the reader a crash course about the basics of Zambia’s significance, one should start by speaking about former President Kenneth Kaunda, the man who is essentially the ‘father of the nation’. In many ways, he was to Zambia what his close friend and ally Julius Nyerere was to Tanzania, and that’s a pragmatic, stable, and decades-long leader who presided over his state throughout all of the Cold War. Just like Tanzania, Zambia was a frontline state fighting against apartheid in South Africa and the remaining colonial governments in Angola, Mozambique, and Rhodesia, and the country was a sanctuary for rebel groups fighting in these neighboring conflicts. Although there were several high-profile incursions against its territory – most notably when the Rhodesian government attacked some of the insurgents there during the late 1970s – Zambia was never formally involved in any conventional war (not even “Africa’s World War” in 1990s Congo), and it thus remained largely untouched by the conflicts that have ravaged Africa over the past half a century.

This deserves further commentary because – like Tanzania – it’s very unusual that such an identity-diverse state could evade domestic and international conflict for so long while its counterparts seemed to inevitably become embroiled in it. Zambia counts 73 ethnic and linguistic groups within its borders, making it less diverse than Tanzania, but still relatively eclectic by any other standard (especially European). The largest groups are the Bemba and the Tonga, comprising 21% and 13.6% of the population and concentrated mostly in the north and south, respectively. Interestingly, former President Kaunda was born in traditionally Bemba northern Zambia to Tonga parents from Malawi, and this ‘minority-of-a-minority’ status might have played a part in why he didn’t promote tribalism during his rule. His assimilation and integration as an ‘outsider’ into local society was an integral part of his personal upbringing, and this formative experience could be attributed with influencing him to pursue an inclusive national identity that emphasized state patriotism over tribal affiliation. It also helped to a large degree that Kaunda was a peaceful anti-imperialist and a stout socialist, two interlinked ideological matrices which obviously had a strong effect on his views. Although it’s possible for a supporter of these ideas to also be a parochial tribalist, that wasn’t the case with Kaunda, who practiced what he preached and put it to the test by forging a unified Zambian identity.

Zambia’s commendable stability also owes itself to its alliance with Tanzania and its close partnership with China. Under the imperial period of British rule, all of Zambia’s connective infrastructure projects were built according to a ‘north-south’ logic, thus making the country completely dependent on Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe) and apartheid South Africa for its connection to the rest of the international marketplace. This became a major vulnerability after the country’s 1964 independence when Kaunda took to actively practicing his anti-imperialist policies and started training and hosting rebel groups from all around the region. In order to retain strategic flexibility and prevent Zambia from blackmail by its neighbors, it looked eastward to ideologically identical Tanzania for a desperately needed alternative outlet to the world. As such, the TAZAMA oil pipeline linking the two countries was completed in 1968, followed by the Chinese-financed TAZARA railroad along mostly the same route in 1975. Taken together, the Tanzanian-linked infrastructure projects gave Zambia the opportunity to more independently practice its anti-imperialist policy, and the railroad was especially pivotal in the export of the country’s copious copper deposits after Angola’s Benguela railroad became inoperable during the country’s post-independence civil war in 1975 and Lusaka opted to diversify its prior export dependency away from Rhodesia. Had it not been for the backup options that Tanzania provided it for energy and commodity market access, then Zambia would have remained fully reliant on the imperialist and apartheid states and thus would have eventually been subsumed by their influence and control with time.

Zigzagging Through The South-Central African Pivot Space

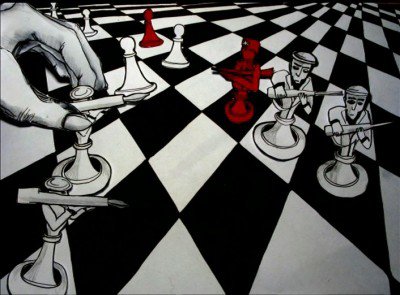

In relation to the infrastructure projects zigzagging through Zambia, it’s apparent that the country serves as the connectivity juncture for the entire sub-equatorial transport network running throughout the region. For this reason, Zambia can be described as the pivot state over this vast space and an object of priceless envy in the New Cold War:

* Red: TAZARA

* Green: TAZARA-Katanga-Benguela/TAZARA-North West Railroad-Benguela

* Pink: Walvis Bay Corridor

* Blue: Zambia-Zimbabwe-South Africa railroad network

* Purple: ZaMM (Zambia-Malawi-Mozambique)

The above map visually depicts Zambia’s geostrategic importance in Africa through the perspective of New Silk Road connectivity. It lies at the center of multiple intersecting infrastructure projects and has the potential for linking them all together to forge an integrated sub-equatorial coast-to-coast transit system in this part of Africa. Furthermore, if an interconnecting route was to be made between Tanzania’s TAZARA and Kenya’s LAPSSET Corridor (i.e. bridging Dar es Salaam and Lamu via Mombasa), then it would be conceptually possible to join Ethiopia’s nearly 100-million-strong marketplace and the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railroad to this transcontinental mainland transportation line. Even barring the expansion of this network past the equator and into the Horn of Africa, the Zambia-intersecting sub-equatorial rail matrix makes the South-Central country one of the continent’s most influential pivot spaces, and accordingly, a very likely victim for Hybrid War.

Cutting The Zambian Knot

Zambia is the key component to the larger transcontinental New Silk Road interconnectivity project that’s taking shape in sub-equatorial Africa, and it accordingly ties all of the projects together into an integrated whole. If Zambia were to be destabilized in any significant way, then it would immediately throw this multipolar vision into jeopardy, either disrupting it partially or wholly, or allowing a third-party state (i.e. the US) to acquire influence or control over the entire structure. For this reason, it’s integral for Zambia to strictly adhere to its traditional complementary policies of independence and stability, as any major deviation from either of these could create problems for the rest of the international network that transits through the country. In evaluating the Hybrid War threats facing Zambia, four in particular stand out, including both general and ‘conventional’ scenarios and those which are more specific and asymmetrical.

It should be kept in mind at all times that the US is known for its phased and adaptive approach to destabilizing targeted countries, and that it doesn’t always aim for regime change per say. Sometimes it’s only hoping that certain events (regardless of the amount of control that the US directly exercises over them) can result in enough pressure that the intended government tweaks their policies in conformity with the US’ interests. Other times, it wants to do more than overthrow the government and actually aims for a ‘regime reboot’, or in this case, a complete domestic reformatting of the country from a unitary republic to a divided federation. Regardless of what the physical result ultimately ends up being, the guiding motivation is always to either disrupt, control, or influence the multipolar transnational connective infrastructure projects in question, which in this case are the five such ones that transit through Zambia.

Color Revolution:

It was evident that Zambia was at risk of an incipient Color Revolution even before the summer 2016 election resulted in a narrow margin of victory for the ruling party. The government was forced to shut down the main ‘opposition’ newspaper after it accumulated millions of dollars in overdue tax arrears, with the owner obviously flouting the law with the expectation that the government wouldn’t dare to move against it out of fear of being accused of an “anti-democratic crackdown”. “The Post” completely misjudged the authorities and was shut down a little over one month before the 11 August election. Shortly after that, ‘opposition’-led clashes killed one person and injured several others, after which the government temporarily suspended campaigning so as to allow both sides to cool down and deescalate the tensions between them.

This worked in the sense of preventing another outbreak of pre-electoral violence, but it didn’t mitigate the ‘opposition’s’ pent-up anti-government energy that eventually burst out in the aftermath of the vote. United Party for National Development (UPND) candidate Hakainde Hichilema alleged that the ruling Patriotic Front led by incumbent President Edgar Lungu defrauded the ballot and illegally pulled off his victory, demanding a recount which he believed would rectify the results and give him the presidency instead. The government refused to cave into the pressure and insisted that Lungu rightfully won the election with 50.35% of the vote compared to Hichilema’s 47.67%, which in turn prompted the UPND to reject the official tabulation. The national situation remains very tense because of this, and it’s possible that some elements of the ‘opposition’ might be planning a Hybrid War to help them seize power.

Regional-Tribal Conflict:

Even if the present drama is resolved, that doesn’t take away from the fact that the country is almost evenly divided into two separate political camps for the second time in just as many years. During the extraordinary 2015 vote that was called in response to incumbent President Sata’s unexpected death, Lungu beat Hichilema 48.33% to 46.67% by the razor-thin difference of nearly 27,000 votes and was therefore accorded with the right to serve out the rest of his predecessor’s term before the next round of elections, which he won by a slightly more comfortable (though still narrow) margin. The geographic nature of this division follows the general north-south split between the Bemba and Tonga’s zones of influence, indicating that tribalism might finally be on the verge of becoming a palpable political factor.

Even though it would be utterly destabilizing to the country’s traditional social and political harmony for this to happen – and likely herald in the sort of violent conflict that has hitherto been a staple of most African nations’ history – it wouldn’t exactly be surprising, since the ‘opposition’ displayed its inclination to politicize tribal identity earlier this year when some of its highest-ranking representations proposed that Zambia “should choose leaders on tribal rotation basis”, which effectively amounts to “Bembas and other tribes [being] excluded from seeking the presidency on grounds of tribe”. The ruling Patriotic Front immediately admonished its rivals for flirting with such a dangerous ideology and warned that “it is outrageous and completely away from established democratic principles upon which our beloved Zambia is built.”

In hindsight and judging by the results of the latest election, this scandal might have been effective in reinforcing the incipient regional-tribal politicized identity that is perniciously creeping to the fore of Zambian politics. Should this trend continue, then it will almost certainly catalyze a larger centrifugal process whereby the decay of inclusive socialist-era Zambian patriotism accelerates to become an all-out rapid post-modern degeneration into regionalized, tribalized, and then perhaps even localized identities that split the country into halves and possibly even divide it further into a multidimensional mix of militantly conflicting variables (“stereotypical African tribal warfare”). More than likely though, the immediate effect of Zambia’s descent into domestic violence would see the western and southern parts of the country teaming up against the northern and eastern ones, though it might not be the Bembas and Tongas that end up starting a war for political power, but the Lozi in “Bartoseland” that spark one for independence or Identity Federalism.

“Barotseland” Separatism And Identity Federalism:

The Lozi account for only about 5.7% of Zambia’s 15 million people, but they’re sparsely spread throughout most of the expansive Western Province and have historic kingdom claims to nearly 44% of the country’s entire territory if one includes their pre-colonial footprint in the contemporary Northwestern and Southern Provinces. The Lozi’s homeland of Bartoseland became a protectorate of the UK in the late 19th century and came to constitute the vast majority of the then-province of Barotseland-North-Western Rhodesia prior to its merger with its counterpart of North-Eastern Rhodesia in 1911 to form Northern Rhodesia, which would later become Zambia after its 1964 independence.

It was right before the country’s freedom from the British that the Barotseland issue returned to the national spotlight, as all sides agreed to the Barotseland Agreement in that year which gave the region broad autonomy over its civil affairs. Kaunda, however, rescinded this in 1969 following a constitutional referendum that equalized each province’s status and tangentially ended up changing Barotseland’s name to the Western Province (with its historical territory in the modern-day Northwestern and Southern Provinces never having been administratively incorporated into its namesake entity). The topic subsequently remained a non-issue for decades until the past couple of years ago when activists made a fuss about it on several occasions and ended up in jail for their attention-seeking stunts. There were even riots in the regional capital of Mungu in 2011 and 2013, but these were quickly quelled by the authorities. Since then, Barotseland has been a slowly simmering problem that threatens to rise to the surface in the coming future, and it might just receive foreign encouragement because of the geostrategic implications that it would have.

Although Barotseland only encompasses the Western Province, its historical claims stretch into the Northwestern one and up to the DRC border, which could theoretically put the separatist-federalist entity right in the middle of the Northwestern railroad project to Angola’s Benguela, or in other words, cut right into the middle of the Southern Trans-African Route’s (STAR) Congo-alternative ‘detour’. The proposed Zambian-Angolan rail connection is much more geopolitically reliable than the Katanga corridor due to the DRC’s inherent instability and proneness to large-scale and disruptive conflict, so the inability to construct the Northwestern railroad due to a possible Barotseland secessionist campaign would deal a heavy blow to the long-term strategic security of STAR.

Moreover, even if a future Barotseland conflict with the newly formed “Barotseland Liberation Army” or other groups never directly interferes with STAR, the ensuing domestic political configuration that might occur through the granting of autonomy to the region or even federal status might produce an uncontainable contagion effect that spreads throughout the whole country, possibly leading to its full-on devolution and the granting of quasi-independent autonomous/federalized status to the Northwest Province as well. Zambia is already giving more power to the provincial and local governments as per the 2013 Decentralization Policy, and this initiative could be exploited by regional-tribal actors such as the Barotse, or even the Bemba and Tonga in the event of large-scale post-election clashes between them, in order to promote a nationwide devolution of power which would transition Zambia from a unitary state into a series of autonomous or federalized statelets.

Regardless if it’s sparked by the Barotseland separatists or not, the nationwide fulfillment of this scenario could lead to a these semi-independent identity-based statelets controlling disrupting, controlling, and/or influencing the five separate multipolar transnational connective infrastructure projects running through Zambia and linking together the whole of Southern Africa, which could thenceforth create a cartographic checkerboard of opportunities for out-of-regional states such as the US to divide-and-rule these vital transit corridors

ULTIMATE DISRUPTOR: Weapons Of Mass Migration:

It’s difficult to predict if, or when, this might happen, but should any form of significant conflict break out in the DRC, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, or perhaps even Angola or Tanzania, then the wave of Weapons of Mass Migration that might crash into the historically stable state of Zambia could totally upend the domestic harmony that’s pervaded the country for decades and push it to the brink of civil breakdown. The ‘opposition’-manufactured tension between the Bemba and Tonga, to say nothing of the separatist desires of a progressively loud segment of the Lozi in Barotseland, could be inflamed and each respective identity group might see a valuable window of opportunity for promoting their agenda amidst the confusion and disorder that a large-scale migrant influx might bring.

It’s not to imply that the arrival of thousands of migrants would instantly lead to a reversal of law and order in the country, but that it would indeed cause a divisive reaction among the locals and cause unforeseen budgetary, administrative, and policing pressures which could in turn worsen existing institutional stresses. Depending on the intensity of the onslaught, it might either progressively or rapidly overwhelm these said entities and contribute to the perception of state weakness – one which opportunistic non-state actors and ‘opposition’ parties might be keen to take advantage of. Despite its location at the crossroads of South-Central Africa, Zambia has yet to experience a massive inflow of migrant/refugees from its neighbors, and even so, it was much more politically and socially cohesive under the Cold War presidency of Kaunda to handle any such contingency. The situation is dramatically different nowadays, and as the elections clearly exhibit, the country is sharply divided into two competing political factions, the balance of which might be disastrously disturbed by the sudden introduction of this rogue and ultra-unpredictable third-party element.

To be continued…

Andrew Korybko is the American political commentator currently working for the Sputnik agency. He is the author of the monograph “Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change” (2015). This text will be included into his forthcoming book on the theory of Hybrid Warfare.

PREVIOUS CHAPTERS:

Hybrid Wars 1. The Law Of Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid Wars 2. Testing the Theory – Syria & Ukraine

Hybrid Wars 3. Predicting Next Hybrid Wars

Hybrid Wars 4. In the Greater Heartland

Hybrid Wars 5. Breaking the Balkans

Hybrid Wars 6. Trick To Containing China

Hybrid Wars 7. How The US Could Manufacture A Mess In Myanmar