How Tony Blair Sealed UK Relations with Egypt’s Dictatorship

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Tony Blair’s visit to Egypt in April 1998 was his first trip to the Middle East since being elected prime minister the previous year.

In Cairo, Blair promoted British arms exports, attended the signing ceremony of a new energy deal with British Gas and announced the creation of an Egyptian British Business Council, telling a business audience that “we should do more together”.

The strategy marked a step change from British policy under Blair’s predecessor, John Major. In July 1995, with Major’s Conservative government still in power, the Foreign Office wrote that “we have friendly but not [sic] particularly substantive relationship with the Mubarak regime”, declassified files show.

The Blair government sought to remedy two problems that had arisen between the two countries.

These were described in February 1998 by Dominick Chilcott, foreign secretary Robin Cook’s private secretary, who wrote: “Mubarak is said to have [taken] umbridge at the lack of high level contact with the government since the election and has been exercised about the presence of Islamic extremists in London”.

“The lack of contact at the highest level galls the Egyptians”, Chilcott added.

Chilcott, now Britain’s ambassador to Turkey, was referring to Mubarak’s accusation that the UK was harbouring Islamic militants, who had targeted Egypt in November 1997 when terrorists killed over 60 people in Luxor.

Mubarak specifically pointed to Yasser al-Sirri who had been convicted in absentia in Egypt in 1994 for attempting to assassinate its prime minister and was living in the UK after applying for asylum.

Despotism

British officials had few illusions about Mubarak, who had held absolute power for 17 years since the assassination of Anwar Sadat in 1981. In advance of Blair’s visit, Sir David Blatherwick, the UK’s ambassador in Cairo, wrote a long analysis of the situation in Egypt, describing it as “in effect a paternalistic despotism”.

He noted that Mubarak, who was “shrewd” and “well informed”, was also “very much in control of what happens in Egypt”.

Blatherwick had earlier written that “Mubarak is Pharaoh”, adding that “all important decisions, and many others, go to him personally” and that “he is surrounded by people who (mostly) protect him from bad news or unwelcome advice”.

But the ambassador added that “Mubarak’s survival, or failing that the survival of the regime, is in our interest”. Not the least of the reasons for this was “the potential of the Egyptian market” and “the good scope for business here”.

Under John Major, the Foreign Office had written that in Egypt the “political system is dominated by the ruling party” while “opposition parties have been rendered impotent by government restrictions”. Added to this were “allegations of corruption involving ministers and members of Mubarak’s own family”.

‘Tight grip of the security apparatus’

Mubarak’s repression was well-documented. In its annual review of Egypt for 1998, Human Rights Watch wrote: “Authorities showed no sign of loosening the tight grip of the security apparatus, and documentation of its impunity — including torture, deaths in custody, ‘disappearances’, and abysmal prison conditions — filled the pages of reports published by Egyptian human rights organisations”.

It added: “Nor did the government take any significant steps to provide additional space to independent institutions, or peaceful political opponents and critics.”

None of this seemed to matter to Blair. The briefing documents that have been declassified pay scant attention to such concerns or to human rights. Rather, in a speech in Cairo on 18 April, Blair chose to directly praise the Egyptian dictator.

He said: “Egypt has been a pioneer in promoting peace and stability across the region. I pay tribute to the leadership he [Mubarak] has shown”.

Lobbying for BAE

Briefs prepared for Tony Blair urged him to “raise defence sales prospects” given that Egypt was an “enormous importer of military equipment”. These “prospects” included military radios, armoured vehicles and Hawk aircraft, officials wrote.

When Blair met Mubarak for 90 minutes on the first day of the trip he told him “defence cooperation was… good” and that he would ask the ambassador “to follow up some points in more detail”.

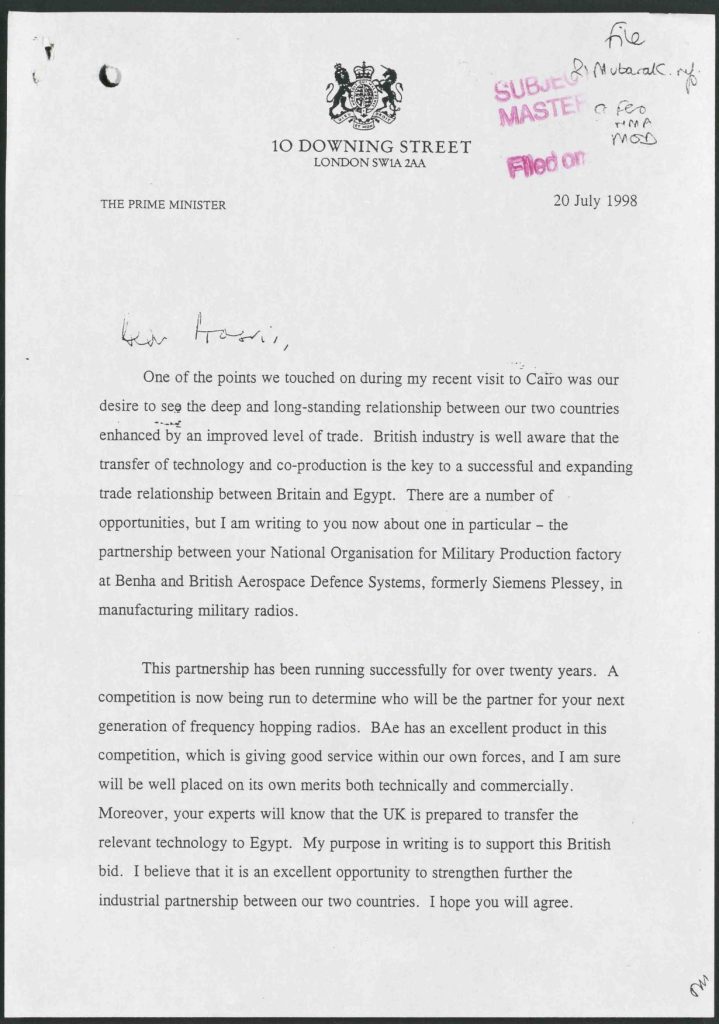

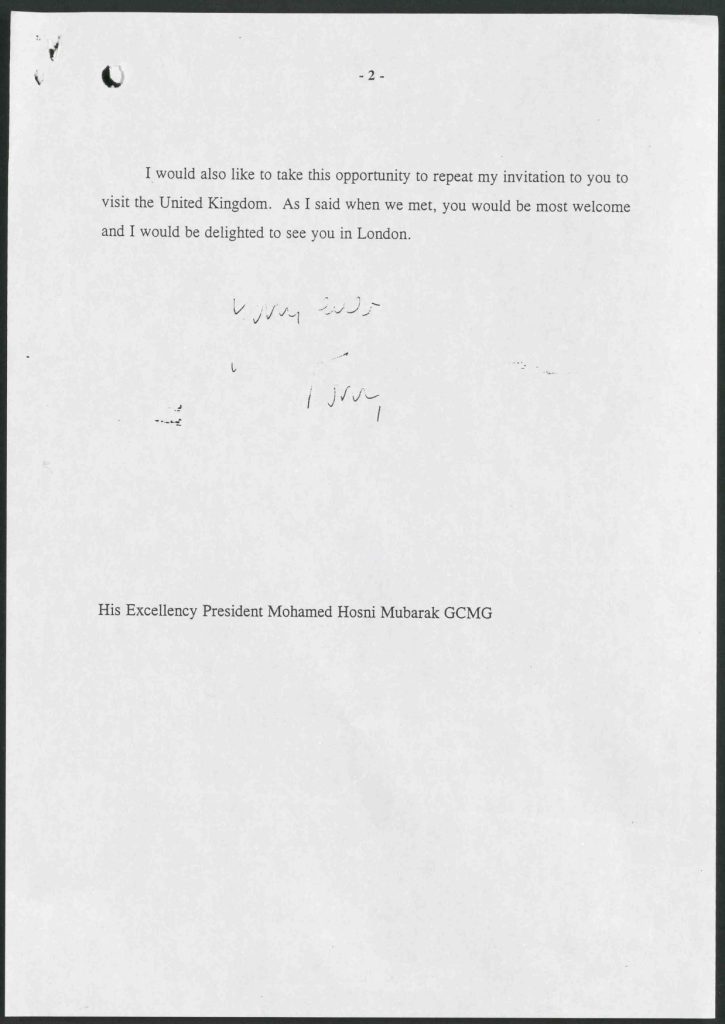

Blair did so himself. Following his visit, he directly lobbied Mubarak on behalf of BAE Systems – or British Aerospace Defence Systems as it was then called. On 20 July 1998, the British prime minister wrote a personal letter to Mubarak asking Egypt to buy military radios from BAE.

“My purpose in writing is to support this British bid”, Blair wrote, adding that “BAE has an excellent product”. The deal would be “an excellent opportunity to strengthen further the industrial partnership between our two countries”, he added.

Blair’s government subsequently approved 550 arms exports licences worth £65m to Egypt.

Letter from Tony to Blair to Hosni Mubarak, 20 July 1998, in National Archives

Energy business

British Gas (BG) chief executive David Varney wrote to Blair in early April 1998 asking if he would attend the signing of a new deal with his corporation to set up the Nile Valley Gas Company while he was in Egypt.

After Blair did so, Varney thanked him saying “Your presence was invaluable in raising BG’s profile in Egypt”.

The brief prepared for Blair by officials noted that a key aim of his visit to Egypt was “to develop our economic relations with what is emerging as an important market”. Egypt was one of the government’s 12 target markets and, in particular, “big new reserves of gas off the north coast are coming on stream (Shell and British gas are both deeply involved)”, Blatherwick wrote.

The new body that Blair launched to promote trade and investment – the Egyptian British Business Council – was “warmly welcomed by the Egyptians”, one UK official wrote.

The UK side of the new council was headed by the chair of HSBC, Stephen Green, and it consisted of senior executives from corporations such as Shell, British Gas, Unilever and Barclays.

The council’s vice chair was Sir Peter de la Billiere, the former director of the SAS who was now with the merchant bank, Robert Flemings Holdings. De la Billiere clearly had high level access to the Egyptian regime: one declassified document shows he personally met Mubarak in March 1997.

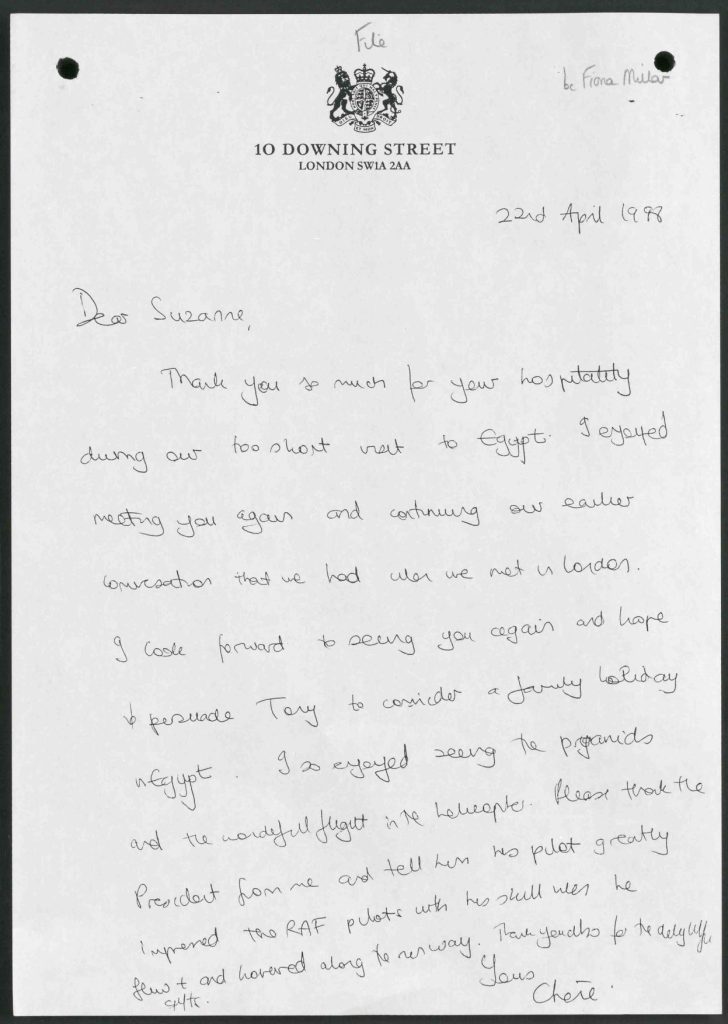

Note from Cherie Blair to Suzanne Mubarak, 22 April 1998, in National Archives

Cherie thanks the president

Blair’s wife, Cherie, accompanied him on his visit and the declassified files contain a draft written note from her to Mubarak’s wife, Suzanne.

Cherie Blair thanked Suzanne Mubarak for her hospitality, writing: “I so enjoyed seeing the pyramids and the wonderful flight in the helicopter. Please thank the President from me”.

In the note, written on Downing Street headed paper, Cherie Blair also told Suzanne Mubarak she hoped “to persuade Tony to consider a family holiday in Egypt”.

She evidently succeeded. Four years later, in 2002, Tony and Cherie holidayed at the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh “as a guest of the Egyptian government”. The return flights were paid for by Mubarak’s government.

‘Laid the foundations’

After the visit, Blair wrote to Mubarak thanking him for the “wonderful hospitality” and saying: “I… believe we have laid the foundations for even better and closer relations between Britain and Egypt”.

Blatherwick agreed, saying that before Blair’s visit “the Egyptians were tending to feel that we were not interested. They have been delighted to find this is not so”.

Mubarak also became more muted about the presence of Egyptian militants in London. By October 1998, trade secretary Peter Mandelson’s assistant private secretary, Zhada Bibi, was writing that “political and economic ties with Egypt are strengthening”.

The UK government continued to back the Mubarak regime under Blair and his successors. Just before Mubarak was overthrown in the popular ‘Arab spring’ protests of 2011, Blair described the beleaguered Egyptian leader as “immensely courageous and a force for good”.

The deepened relationship Blair established was also a precursor to that with the country’s current pharaoh, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Blair welcomed the Egyptian army’s seizure of power in 2013 which brought Sisi to power and then went on to advisehim.

The UK has supplied Egypt with £297m worth of military equipment under Sisi’s regime, which has created an unprecedented human rights crisis in the country.

BG was acquired by Shell in 2015. It is their interests, alongside BP’s interests in Egypt, that UK foreign policy now promotes, while Whitehall largely ignores the country’s increasing human rights disaster.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Mark Curtis is the editor of Declassified UK, and the author of five books and many articles on UK foreign policy.

Featured image: Tony Blair with Hosni Mubarak. (Photo: Peter Macdiarmid / Getty)