|

The dissolution of Haiti’s parliament on January 12, 2015, coming so close Martin Luther King Jr’s birthday, brings forth reflections on the utility of non-violent action as a tool to fight a foreign occupation.

An occupation, of course, is not the same as the struggle of a disenfranchised group of people for equal rights within a country where there is a pretense of fairness and the rule of law. A foreign occupation is a project of conquest that is meant to crush the spirit of a people and subjugate them, unravel the very fiber of their society, even eradicate them in cases. Foreign occupations usually involve murder, rape, pillage, the imposition of an alien culture, and the removal of young children from their families. They should be fought by any means necessary. Here I dissect the practice and validity of non-violent action, as MLK might have encouraged Haitians to do, to identify approaches that might be adapted to suit our own situation, place, and time.

Stuck in time in Washington, August 1963

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr has become fetishized, stuck in most people’s minds in the quarter of an hour of his “I have a dream” speech, although he had devoted many years of his life to the fight for equality in the United States and redefined his tactics countless times. The speech, which took stock of the dire situation for blacks in the US 100 years after emancipation, was delivered on August 28, 1963 to the people who had attended the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This was the first such march to be extensively televised and the biggest one, with about 250,000 people. The multiracial audience hailed from many organizations, including MLK’s own Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), religious groups, and labor unions.

How it must have felt to hear MLK’s words when even today, a film of the event can be cathartic! One could not fail to recognize that a man of great historical importance had spoken. The force of his delivery was only part of it. Everything at the march, every camera, focused on him. He had demonstrated that his organization could publicize the event far and wide and coordinate the transport of a quarter of a million people to Washington: an extraordinary achievement. His wife beamed with pride. His older children, who had been harassed by their peers for having a “criminal” parent who was always in and out of jail, witnessed their father get introduced as “the moral leader of our nation” before delivering the closing speech of the march.

Two days later, William Sullivan, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s intelligence division, would write to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover: “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.” From that moment on, a campaign was formulated to discredit MLK in the press, with churches, universities, the Nobel Committee, and every other aspect of his life. This persecution would take the same form as the FBI’s attacks on perceived enemy agents and continue until MLK’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

Aimless marches imply a transfer of power

Incredibly, these attacks on MLK began after he made a tactical change from direct actions, where he and others deliberately broke what they deemed to be unjust laws, to completely legal marches. In the March on Washington, a quarter of a million people were peacefully ushered to the country’s capital to make various demands from the government. Inspect the posters from any section of the march, and they will shout back a cacophony of demands for: an end to segregation in public schools, voting rights, jobs, $2 per hour minimum wage, self government for the predominantly black District of Columbia, and so on. All the posters had been prepared by the organizers. The eloquent writer James Baldwin was prevented from speaking, for fear that he might say something inappropriate. The march itself covered less than one mile: from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial.

Surely this was inoffensive enough. But was it really? What MLK had shown, and what was clear to the FBI, is that he could gather a massive crowd and utterly control it. A quarter of a million people with countless grievances sat alongside like-minded people and listened to songs and speeches for several hours. This amounted to more than one million man hours. Such time could have been used instead to construct something magnificent in a massive “barn raising,” so to speak. Alternatively, it could have been spent to block all activity in Washington or destroy the city. The latter had certainly occurred to law enforcement, whose presence was unprecedented. By sitting still for several hours, the people at the march divested themselves of their own power and gave it to their leaders, who went to meet with President Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson after the march to discuss civil rights legislation. Such a transfer of power from the people as a background to a series of negotiations is the essence of large, seemingly aimless marches.

Empowering marches with a mission and destination

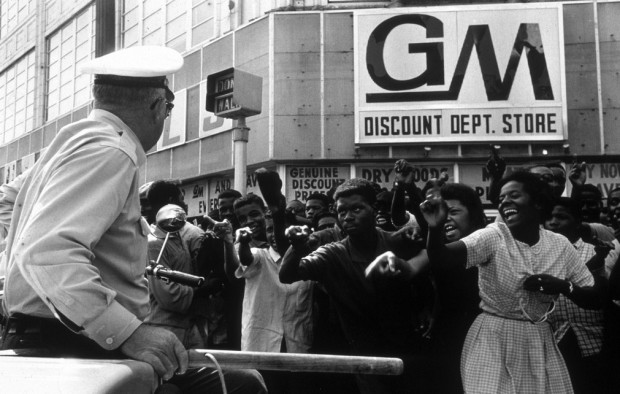

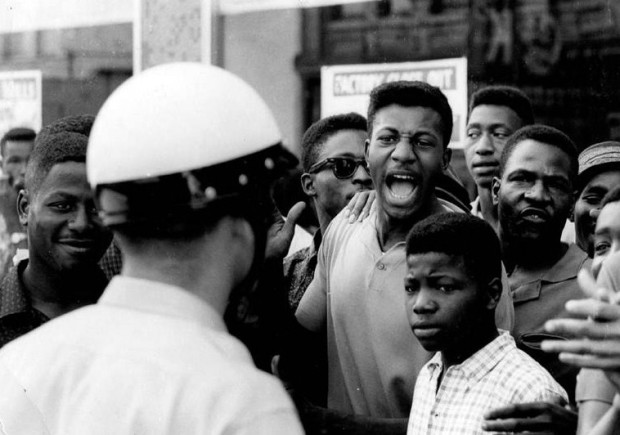

The march on Washington stands in great contrast to the Birmingham campaign, only a few months before, in April to May 1963. This campaign empowered the marchers, who had an aim and a destination. In these actions, MLK and other SCLC organizers led black citizens, including many students, to specific sites in Birmingham, Alabama, to desegregate them. MLK participated in the most radical part of the campaign, which was called “Project C,” for confrontation. Its aim was to challenge the city’s racial laws, which sanctioned the segregation of public spaces like parks and buses, and commercial facilities such as stores. One memorable such venue was the Woolworth’s lunch counters whose desegration is well documented. To attract public scrutiny and national sympathy, the campaign deliberately drew and exposed the law-enforcement response, which involved attacks on the protesters with police dogs and firehoses. MLK’s arrest in Birmingham on April 12, 1963, rendered famous by hisletter from Birmingham jail, was his 13th arrest. This letter to a group of religious leaders stands as a testament to his dedication to direct action and a timeless retort to those who call for patience and moderation in the face of intransigence and abuse.

By 1968 MLK had returned to direct action to confront racism in parts of the US where it was not institutionalized but was actually more virulent. In March of that year, just days before his assassination, he traveled to Memphis to support a sanitation workers’ strike. Two city workers had been crushed to death by a dysfunctional dump truck that should have been retired. In response, about 1,300 garbage collectors, all of them black males, walked out on the job. The strikers called for recognition of their union, better wages, and improved safety, but their demands and marches to address the Mayor at the City Hall were consistently met with police attacks and tear gas. Civil rights groups like the NAACP and Community on the Move for Equality (COME) organized students to march with the workers. This strength in numbers should have been helpful, but some of the students were agents provocateurs who turned one major march into a riot, creating yet more paranoia about MLK’s perceived power to start a race war.

MLK did not survive to see the strike to its conclusion, and though it is difficult to know exactly how and when the strike would have ended if he had lived to see it through, it is certain that one of his approaches would have been to expand the strike to the entire city so as to bring the mayor of Memphis to the negotiating table. At the least, this would have created solidarity with other sectors of the city and politicized the population. A strike, where the injured party reaches out to a larger group, represents yet another approach to non-violent resistance. The strikers do not relinquish their power to a group of leaders but, rather, become more empowered by broadening their support base. This is not, however, how the strike ended in Memphis. Instead of expanding the strike, the publicity of MLK’s death was exploited to organize a massive march led my MLK’s widow, Coretta Scott King, and to pressure the mayor into an agreement.

The case of Haiti

All non-violent action boils down to one principle: non-cooperation in one’s own repression. Currently a multinational group of occupiers live in Haiti in relative luxury, and they depend for all their services on the support of Haitians.

The United Nations (de)Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH)

As of September 2014, MINUSTAH boasted of having a “local civilian staff” of 1,169 people, but these are merely the Haitians on MINUSTAH’s official payroll. If one includes the servants, cooks, janitors, etc., the real size of the Haitian support for this military and police force of about 8,000 people exceeds 11,000. Yet Haitians almost unanimously reject the presence of MINUSTAH in the country.

Non-governmental organizations (NGO)

The NGOs in Haiti, many of which are religious based and look on Haitian culture with disdain, are equally reviled by Haitians. The majority of NGO members live in gated, whites-only communities, with villas, swimming pools, restaurants, security guards, and a retinue of Haitian servants. Immediately after the earthquake, the number of NGOs — not NGO members but NGOs — climbed to the improbable radio of 1:600 Haitians. Back then I remarked that “If one could extrapolate to one NGO per Haitian, the Haitian would be dead.” With regard to the cholera epidemic, I noted that the strongest and best-sustained efforts to control the epidemic had come from Cuba, and not from the medical NGOs, which had, for the most part, exploited the situation to raise funds and solidify their own status. Specifically, I observed that: “Like opportunistic parasites, the NGO and their entourage feed on misery, and the misery increases in proportion to their numbers. They must not be allowed to continue benefiting from Haitian deaths. They must be starved of support so Haiti may become well again.”

NGOs are currently tolerated in Haiti only because they have caused the dismantlement of so many institutions that numerous Haitians have come to depend on them for their livelihood. NGOs take up the best space in an island nation where housing is at a premium, but that is not their worst impact. Their most insidious role, and the one for which so many of them are paid handsomely by USAID, is to serve as a wedge between political organizers and the people. Specifically, in any revolution there would be a government in waiting, providing services to the population and at the same time raising its consciousness and radicalizing it. NGOs prevent this contact between leaders and the people. For this function alone, they deserve zero tolerance.

Call for a general strike throughout Haiti

Haiti’s unemployment rate exceeds 85 percent, and the last remaining sectors of Haitians who are employed by the state have not been paid for months, or even years. The expressed mission of MINUSTAH is to stabilize this untenable situation. MINUSTAH’s military force, together with the militarized “Haitian” police that it is building, work jointly with the NGOs to undermine any impetus to sovereignty. Furthermore, a tontons-macoutes-like paramilitary army is quietly being built in Ecuador for deployment in Haiti in Summer 2015; it is composed only of people who have been hand-picked by Martelly and are loyal to him. Therefore, time is of the essence. A delay of a few months in taking non-violent action against the occupation is likely to make the difference between a peaceful transition and one in which the population is punished with considerable bloodshed.

The situation in Haiti calls for a sustained general strike throughout the country, with enforcement by the massive numbers of the unemployed, and with its major targets being the UN and NGOs. The occupiers must not be allowed to luxuriate in an island paradise while they create a living hell for the vast majority of Haitians. Their comfort must be disturbed. The entire country: every sweatshop (free-trade zone), all travel, all ports, must be shut down until the occupiers are gone. In support, the diaspora should target UN and NGO offices in its own cities outside of Haiti for coordinated protests to raise consciousness about the situation inside the country.

News Junkie Post Editor’s Notes:

An excerpt from this article about the call for a strike in Haiti is available in French.

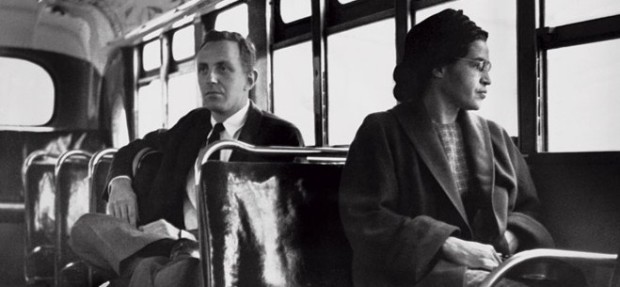

Photograph one, from the archive of Ansel; two, from the archive of Jared Enos; four, five, six, seven, eight and nine by Charles Moore; eleven, from the archive of Save the Children; twelve and thirteen by Dan Lundmark.

|