How Oman Became the Chief Architect of Arab Normalisation with Syria

By maintaining ties throughout the war, Muscat gambled on Assad and won. Now it leads the way as countries recalibrate their relations with Damascus

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg.

***

As relations between Syria and its neighbours warm again a decade after the Syrian war first broke out, Damascus has become a popular destination for Arab dignitaries.

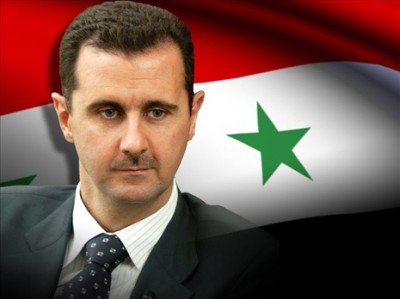

Omani Foreign Minister Sayyid Badr al-Busaidi was not only the most recent top official to meet President Bashar al-Assad in January, the visit represented the leading role his country is playing in Arab normalisation with Syria.

Syria’s days of long isolation and regional disfavour are starting to shift – albeit gradually – and much of this reintegration is down to the critical role of Muscat and its gamble on keeping clear lines of communication and ties with Damascus at the worst of times.

In implementing a non-interventionist foreign policy that has enabled Oman to play a prominent role in the Syrian diplomatic scene, the sultanate will likely reap rewards going forward as more Arab states return to Damascus, however long or difficult that process may be.

However, wider regional rapprochement with Assad is a highly complicated process, not least due to US and European warnings. Saudi Arabia’s refusal to commit to engagement under current circumstances makes things even trickier.

Nonetheless, the fact the Syrian government has achieved such significant progress with reintegration after the war made it a pariah in the region and much of the world, is fundamentally down to the efforts of Oman.

And Syria is certainly grateful.

“It is no secret that our bilateral relations with Oman are very good and have always been, this will continue for the foreseeable future,” one Syrian diplomatic source told Middle East Eye.

Muscat leads the way

Oman has long had a reputation for rarely arguing or taking sides when it comes to diplomatic relations and political disputes, preferring a peacemaker role rather than confrontation.

Much of this Swiss-like neutrality emanates from the core policy principles of Oman’s late leader Sultan Qaboos, who sought to always administer a pragmatic doctrine when dealing with volatile and bickering neighbours in a turbulent region.

Oman refused to enter the Saudi-led group seeking regime change in Syria that emerged in 2011. In fact, it went in the opposite direction, and even sent its foreign minister to Damascus in 2015 at the very height of the military conflict.

Yusuf bin Alawi, then Omani foreign minister, at the time was engineering a return for Syria to the Arab fold, and even seven years ago said he was seeking “ideas proposed at the regional and international levels aiming to help resolve the crisis in Syria”.

Aron Lund, an analyst with the Century Foundation think tank, told MEE that “Oman has a talk-to-everyone attitude to diplomacy, and it is deliberately standing a little bit aloof from its Gulf Cooperation Council neighbours”, adding that they “kept the relationship alive and fished for mediation opportunities”.

Oman has consistently led the way for Arab normalisation.

Sultan Haitham bin Tariq was the first Gulf leader to congratulate Assad on his re-election in 2021. His cable of congratulations expressed best wishes to the president in leading the Syrian people towards further aspirations of stability, progress and prosperity.

The sultanate was also the first Gulf state to reinstate its ambassador in Syria, and it greeted Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad on a three-day trip to Oman back in March, where the Syrians expressed renewed hope for readmission into the Arab League.

In paving the way for other countries such as the UAE, which has recently aggressively sought to normalise relations with Assad, Oman has been a trendsetter.

During Busaidi’s January visit, the Syrian Parliament Speaker Hammoud Sabbagh described Oman as a crucial ally, saying: “The brotherly sultanate has stood by Syria in its war against terrorism.” This type of praise is usually only reserved for Iran or Russia, Assad’s two greatest backers.

Roadmap for the future

From here, Oman seeks ever further cooperation. Busaidi has intimated that mutual visits will step up as ties grow.

While other Arab countries are following Oman’s lead, there are still limitations to overcome.

Much of the Arab world is still wary of Syria’s close ties to Iran, and Damascus doesn’t have much to offer economically, as it is heavily sanctioned. Reintegration with the Arab League would be significant, but it really rests on creating a better relationship with Saudi Arabia, which is yet to be convinced.

However, this hasn’t prevented states such as Egypt from actively trying to facilitate Syria’s return to the regional body. Last month, Egypt’s foreign minister said:

“We hope that conditions will be available for Syria to return to the Arab domain and become an element supporting Arab national security. We will continue to communicate with Arab countries to achieve this purpose.”

It is no coincidence that he said this standing alongside Busaidi in Muscat.

Ultimately, Oman has gambled on the situation in Syria and won. “Although several Arab countries kept their Damascus embassies operational, Oman was ahead of the rest in engaging on high levels with the Syrian government,” Lund explains.

But with Syria devastated economically and yet to be united, what can the war-torn country offer Oman? Lund doesn’t see much current benefit.

“Syria itself seems to have little to offer Oman at the moment. Should Western sanctions be withdrawn or significantly lightened, and if Syria begins to recover economically, it may turn out that Omani investors have a leg up on the competition,” he tells MEE.

“But that’s hypothetical at this point, and I doubt Oman pursued this policy thinking it could score big economically.”

Moreover, Syria’s readmission into the Arab League is not a certainty at this point, and will require some concessions from Damascus, as well as Saudi Arabia’s approval. Also, other countries such as Qatar and Morocco have been vehemently against Syria’s re-entry. Arab League Secretary-General Ahmed Aboul Gheit said recently that the “necessary procedures” for Syria’s return were not yet fulfilled.

This hasn’t prevented a flurry of activity towards Damascus.

Jordan, for instance, fully reopened its main Nassib border crossing with Syria last September, a move that acts as a boost to both the Jordanian and Syrian economies, not to mention serving as a marker for the reintegration of Damascus into the Arab economy.

Bahrain also followed the trend and appointed its first ambassador to Syria in almost a decade.

Ultimately, the role of Oman in cultivating a positive relationship with Syria was in Muscat’s view vindicated by Assad emerging victorious in the war.

With that cultivated link already in place, Muscat can take much credit for reintegrating Syria back into the Arab fold, and in return it will have an enormous line of thankful credit in Damascus – and not least a prominent role in brokering Syria’s Gulf relations in the future.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @globalresearch_crg. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.