|

All Global Research articles can be read in 27 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

First crossposted in October 2020.

The Panama Canal project is much older than just the US imperialistic endeavor and completion of the 20th century that most people associate it with that led to the birth of a new republic.

Leaving aside all issues regarding the indigenous population of the Americas, their suffering and their contribution, this article will focus only on the actions and plans of European conquerors with regard to the canal.

To be fair we have to say that the first well known Western man looking for an imperialistic trade water-route to Asia connecting the Atlantic and the ‘Southern Sea,’ (an early name for the Pacific Ocean in the first decades of the European invasion: ‘Mar del Sur’) was Christopher Columbus in the journeys that followed his first ‘discovery’ expedition, although he never actually reached that vast ocean. Historical chronicles and books teach us that later on Vasco Nuñez de Balboa and his men, following Rio Chagres, were the first Westerners to wash themselves in the Pacific after crossing what would become known as the Isthmus of Panama. But it’s quite unknown that even the Castilian-Extremaduran conqueror Hernan Cortes – worldwide-known for his victory and destruction of the Aztec social system and culture – launched himself into that adventure. And it is also unknown to most that since Cortes’ enterprise of the 16th century, many projects to find a route and even to build a canal linking the two oceans were presented to Spain’s’ king by Spanish individuals and institutions.

Vasco Nuñez de Balboa’s expedition. Source: Wikipedia.

Later on, that pathway became such an important ideal imperialistic tool for European powers that they started to fight for the possession of those lands, long before the French started the excavations for the canal in the 19th century and the United States of America completed it in the 20th. Indisputably, the US was not brighter than others. At that point in history such an idea was feasible because the US could learn from the technological, scientific and geographical knowledge and the failures accumulated in the previous decades and centuries by the earlier attempts at the canal. This, of course, is how human knowledge, including technological achievements, is built up.

The Conquistador and the Jungle

Hernan Cortes (1), and his contemporaries, thought it was not impossible to find a water-passage towards the Spice Islands. It was no consolation to know there was already a path to the Pacific through the Magellan Strait or around Cape Horn in Southern Patagonia which was a long and dangerous route to Asia that started to be used by Europeans from 1520. Cortes’ intuition told him it was possible to open another, easier and shorter way. Obsessed with the idea it could be through Central America, in 1524 he sent one of his men, Cristobal de Olid, to ‘Hibueras,’ the name given by Columbus to Honduras due to her deep bays.

After arriving de Olid was convinced by other conquistadors and decided to free himself from Cortes and to accomplish the enterprise for his own glory. It was a death sentence. As soon as Cortes was informed of de Olid’s plan he sent a loyal man of his, Francisco de las Casas.

Helped by a storm de Olid was able to imprison de las Casas. But after a little while, de Olid started to pay attention to his prisoner’s words and thought he could convert him into an ally. It is said that while having dinner together one night, de las Casas raised his hand, caught his host’s head and stuck a knife in his throat!

Anaware of what was going on in Honduras, Cortes was anxious. He thought that due to the distance the temptation was too strong for his emissary and decided to undertake the feat himself. With a little army he set off for the ‘Hibueras’ lands. It was a bad decision. Looking for a waterway, the luxuriant jungle prevented him from passing and disoriented him. He ended up losing his way and his army. One by one his men fell, and also his native hostages, among them the last Aztec Emperor Cuauhtémoc. Fearing an Indian revolt, Cortes hung all native captives after accusing them of treason. In the end, exhausted by the useless exploration he finally concluded that he could trust las Casas’ loyalty and returned to Vera Cruz, where other conquistadors thought he was already dead and had already planned to succeed him. In European history, this was the first attempt at finding a waterway connecting the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Other Spanish Projects

In 1524, the same year Cortes sent de Olid to Honduras, Charles I of Spain, better-known as Charles V King of Spain, Aragon and Emperor of the Holy Roman-German Empire, suggested digging a canal in order to more easily trade and travel to South America. In 1529 a first project was presented but the technological and scientific knowledge of the time did not allow its materialization.

Later on, as shown by British historian Hugh Thomas, Gaspar de Espinosa y Luna, a Spanish conqueror, politician and businessman based in current Peru – who financed the expeditions of Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro against the Incas (1532), proposed to the Council of the Indies (the most important administrative organ of the Spanish Empire for America and the Philippines) the digging of a canal and the creation of an alternative route. Only the road from Panama City (facing the Pacific) to Camino de Cruces City (on the banks of the river Chagres), from where the merchandise would arrive to the Atlantic on boats, was carried out and this became the main colonial route to the Viceroyalty of Peru (Spanish South America) until the XIX century.

In the middle of the XVI century Antonio Galvão, a Portuguese sailor, stressed again the need of an artificial canal, which became a trendy intention anew. But in 1590 the Spanish Jesuit missionary and naturalist José de Acosta reported about the difficulty of connecting the two oceans as some were requesting while warning of the strategic risks its use by Spanish enemies could mean. Later on, under the ruling of Philip III (1598-1621) the Council of the Indies blocked a similar project commissioned to Dutch builders exactly for those reasons. History also reports of British people occupying lands in what is known today as Panama with the same purpose. Then the idea of building a water-route disappeared for some decades, until the 19th century when the famous German geographer Alexander Von Humboldt revived it to invigorate trade and the flow of people through a canal. And thanks to Von Humboldt, France, the United States and Great Britain became very interested again.

A Brief and Approximate History of the Panamanian Territory

In the colonial period Panama was the northernmost part of the Viceroyalty of Peru (Spanish South America). During the first decades of Spanish colonization, Portobelo, on the Atlantic side of the Isthmus, was the main harbor for all goods travelling from South America to Spain and Europe and vice versa as the routes through the Magellan Strait and Cape Horn were considered not only too long and expensive but also too dangerous. After a few decades the Isthmus and its Portobelo port lost its unique strategic importance as Cartagena de Indias, in current Colombia, became another vital harbor of Hispanic South America.

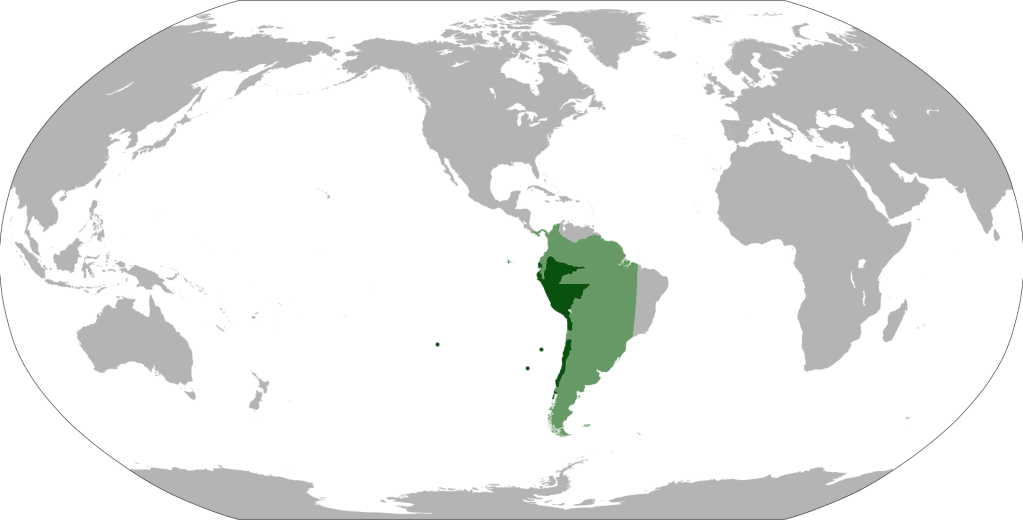

Viceroyalty of Peru in the first centuries (dark and light green). Source: Wikipedia.

In 1739 the northern part of the Viceroyalty of Peru was spilt up and a new Spanish administrative area, the Viceroyalty of New Granada, was established. This new division was considered necessary in order to counter the increasing French and English smuggling and improve the protection of the area against the frequent marine attacks carried out by foreign European powers in the area (mainly England and Holland). The capital of the new-born viceroyalty became Santa fe de Bogota, the current Colombian capital. Within its territory Panama was included.

After independence from Spain, in 1821, Panama became part of the Republic of Gran Colombia which consisted, more or less, of today’s Colombia, Venezuela, Panama and most of Ecuador. In 1830, 9 years later and nearly 90 years after the first administrative dismemberment of the Viceroyalty of Peru, from the Viceroyalty of New Granada were born, roughly, the Republics of Ecuador, Venezuela and Gran Colombia. The territory of Panama was part of the latter.

The fathers of Hispanic American Independence and the canal

It is little-known that heroes of Spanish American independence were aware of the importance the Panama canal would have in the future of trade and it is quite unknown that the most eminent forefather of these movements, Francisco de Miranda from Caracas – who conceived of the union of Hispanic American territories through an Inca Federation – even offered its construction and a shared control of it to the English, historically considered the most seasoned enemies of the Hispanic world.

”On the 27th of March 1790, Miranda presented his first ”Plan for the constitution, organization and establishment of a free and independent government in Southern America” (meaning Hispanic America) to the British prime minister William Pitt. In exchange for financial and military support, Miranda offered to England trade preferences, a participation in the exploitation of Hispanic American riches and the possibility of building a navigation canal in the isthmus of Panama” tells historian and philosopher Carmen L. Bohórquez.

”All major world powers thought of building a canal through the isthmus of Panama as planned by Humboldt. Liberators Simon Bolivar and Francisco de Miranda offered the British rights over the canal in exchange for weapons and support against the Spaniards in their independence struggle as they considered Great Britain their natural ally against Spain. During the Pact of Paris in 1797, Miranda presented his idea of opening a canal in Panama or Nicaragua, ”the fast and easy communication between the Atlantic Ocean and the Southern Sea (Mar del Sur), will be for England of great interest,” documents Patricia Galeana in her bookEl Tratado Mc Lane Ocamo, la comunicación interoceánica y el libre comercio. Afterwards, tells the historian, ”Colombia sent an envoy to London with the objective of obtaining a loan and involving British capitalists in the construction of the canal.”

France, England, the United States and the Panama Canal

Due to the strategic importance of the Isthmus of Panama – the thinnest mainland of the Americas – allegedly in the second decade of the 19thcentury New Granada started receiving proposals for the realization of the canal but all were refused as Bogota thought it should be built with its own resources and administered locally.

By then Spain was practically already knocked out. Hispanic American independent countries and its elites were in turmoil. Most of them were militarily and financially weak or already under the orbit of the Anglo-Saxon and French Empires. The Brazilian elite were not interested much in their neighbors and since the beginning of the century were deeply involved with the United Kingdom. Therefore there was plenty of room to fill the void.

In 1846 the Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty was signed between the Republic of New Granada and the United States of America. In summary, the fundamental clause established that ”the citizens, ships and merchandise of the United States will enjoy the ports of New Granada, including those of the Isthmus of Panama, of all franchises, privileges and immunities, regarding trade and navigation; and that this equality of favors will be extended to the passengers, correspondence and merchandise for the US, that transit through said territory.” Furthermore it was given to the former British colony the right to build a canal in the New Granadian territory. But London was not so happy about this.

In the same years England seized territories in present Panama, Nicaragua and Honduras. For the US’ elite these occupations were a barrier to its 1823 Monroe Doctrine – ‘America for the Americans’ – and its 1845 Manifest Destiny ideology – a cultural belief that the US is destined by God to expand its dominion and expand capitalism and its ‘democracy’ over the Americas. The barrier was demolished with the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty signed between the USA and Great Britain in 1850. Among its most important known points were that neither one nor the other would keep for itself exclusive predominance over the canal and both would protect it. Many have seen in this treaty an act of respect towards Latin American countries, but it was principally an agreement of power-sharing over the area.

Even so, at the end the Anglo-Saxon project of a canal was not realized. And it ended up in the hands of the French.

Fernand de Lesseps, after a long career as a French diplomat and following his success in the construction of the Suez Canal in 1869 (it seems the first project was made in the Republic of Venice in the 16th century), was appointed by the Paris’ Société de Géographie as president of the Panama Canal Company in 1879. But the French project failed as de Lesseps did not take into account the different environmental conditions: in Panama canal-workers had to deal with a jungle and not a desert. He did not take into consideration the different water-levels between the two oceans and projected a sea-level canal. The company resulted in a huge scandal in France and in 1889 went bankrupt and lost its French investors’ money. It was in that moment that Lesseps and other important, rich French businessmen involved in the project went to the USA in search of economic support. By then Panama was still part of New Granada.

The Proclamation of Independence of Panama

In the beginning the US was interested in building the canal in Nicaragua but under the pressure of the French lobby, in 1899, a US commission was set to determine which site was better, Nicaragua or Panama. Nevertheless in 1901 US Secretary of State John Hay pressed the Nicaraguan government for its approval: Nicaraguan elite would receive $1.5 million in ratification, $100,000 annually, and the U.S. would “provide sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity.” Nicaragua’s elite were not satisfied. They asked for 6 million of ratification instead but the project got blocked by a US court decision. Undoubtedly the influence of the French in the final decision was fundamental. Nicaragua was ruled out. In 1901 the United States and England signed the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty in which both countries did NOT recognize Colombian sovereignty over the isthmus and gave it the status of ‘area of international importance.’

The treaty nullified the 1850 Clayton-Bulwer concordat (which arranged a shared authority over the canal) and gave the USA the right to create and control it. In this way Colombia was forced to cede and in 1903 an agreement was reached with the government of Bogota. The Hay-Herrán Treaty was signed but the Colombian Senate rejected it worrying about its territorial sovereignty. The rejection provoked a world scandal among nations ruled by imperialistic elites: how dare Colombia make decisions over its own territory!

Another cartoon of 1903. It depicts the French businessman De Lesseps (left) and US president Theodore Roosevelt. Source: Wikipedia.

Immediately after such a refusal, Washington (USA) engendered the independence of Panama supported by a power-greedy Panamanian elite and by a small portion of local people and on November 3, 1903, Panama became a new republic, receiving $10 million from the US. No blood was spilled. Theodore Roosevelt, president of the US, applied his famous Big Stick Policy sending the US Navy to the Colombian offshore while an Anglo-German blockade was stationed against Caracas (Venezuelan capital). Panama’s new government also gained for the canal an annual payment of $250,000 for ‘rent’ and guarantees of independence while the US obtained the rights to the canal strip “in perpetuity.” As was to be expected, on November 6 Roosevelt’s government was the first to formally recognize the new-born republic, followed the day after by France. And before the end of that month another 15 countries of Europe, America and Asia did the same.

At that point the deal was made. The United States paid the French 40,000,000 dollars for the trains, machinery, excavations and rights – an enormous amount compared to what it was offering to Nicaragua (1.5 million initially) or Panama (10 million). On this particular issue it’s worth noting that French author Gabriel J. Loizillon in his book Philippe Bunau-Varilla: L’Homme du Panama claims that the enterprise used by the US for the construction of the canal was that of Philippe Bunau-Varilla who earlier was a de Lesseps’ subcontractor and later greatly invested in the second French company for the construction of the canal. Bunau-Varilla was one of the main French lobbyists working within the US. It is said that before the birth of the republic of Panama he had already drafted the new Panamanian constitution, come up with the flag, and military establishment, and promised to float the entire Panamanian government on his own checkbook.

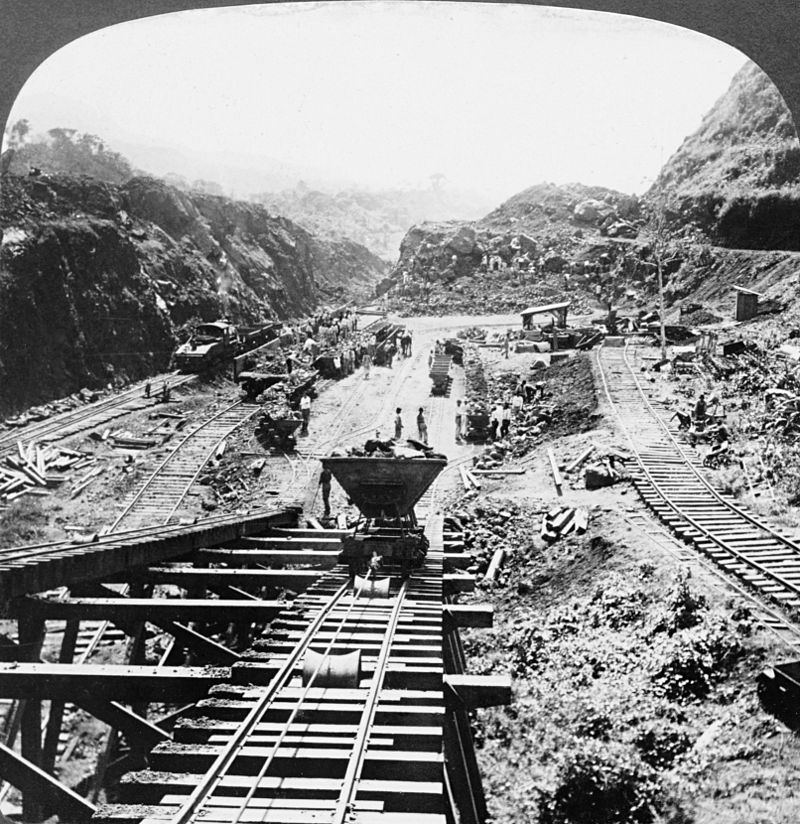

Construction of the Panama Canal in 1907. Source: Wikipedia.

The Panama Canal was inaugurated in 1914. It is reckoned it costed the lives of 20,000 workers under the French and an equal amount of men under the US – under the French principally coming from the French Antilles, later from the Anglophone Caribbean islands. Its construction also destroyed the lives of thousands of people living in the area that were expropriated and the local ecosystem.

The US benefited millions from the canal in exchange of an annual rent of $250,000 dollars. After the opening the main beneficiaries were US corporations belonging to tycoons like the Rockefeller’s Standard Oil (later Exon, Exxon, Esso, Mobil and many others) and banker Pierpont Morgan (J.P. Morgan & Co., Federal Steel Company, Chase Bank). Morgan had also been appointed in 1903 as fiscal agent for the newly independent Republic of Panama and carried out his ‘duties’ through US and French financial institutions. Not much has changed since then. After the canal returned to Panamanian sovereignty in 1999, it keeps working principally with countries under the orbit of the US Empire. The canal is mainly used by the US, followed by China (the US’ biggest goods trading partner), Chile, Japan and South Korea.

But business is business and the golden age of the Panama Canal could be close to its end. The Northwest Passage in Northern Canada could be the future cheaper and shorter waterway between the Pacific and the Atlantic due to climate warming. This could be a great loss for the corrupt Panamanian elite, but not a real tragedy. If the world destructive and selfish capitalist system does not fall, Panama’s tax haven structure (2) could be enough to keep it wealthy and well-afloat in the upcoming years – a wealth from which about 37% of Panamanians are completely excluded, 4 out of every 10 persons in the country.

Indisputably, the history of the Panama Canal doesn’t show us only its imperialistic function, its corrupt character and all the unjustifiable sacrificial death it has produced for the sake of greed, power and money. But also that the project, for what we know, dates back to 1513. Its construction was possible thanks to the knowledge and ideas gathered over time. Columbus’ journeys, Balboa’s expedition (1513), the Spanish construction of the Viceregal Peruvian Northern trade route through the Rio Chagres, de Lesseps’ failures…These are some ‘contributions’ I have mentioned in this report but the list could grow exponentially even embracing cultures that today have disappeared. And this is valid not only for the Panama Canal, but for all human knowledge and achievements. They don’t belong to one person, one culture or one nation but are the result of a slow and long cross-border process.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Notes

(1) Most people believe Hernan Cortes was an uneducated Castilian man. It’s not true. He was a poor aristocrat, who also studied at the University of Salamanca and according to historians was a cultured man.

(2) Panama represents an important but only a small part of the world tax heaven structure. Most tax and laundering paradises are under London’s control in British extraterritorial jurisdictions.

|