|

All Global Research articles can be read in 27 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

“We are willing to help people who believe the way we do.” —Dean Acheson, Truman’s Secretary of State, 1947

Introduction

I cannot stress enough the overwhelming toxic spell that Cold War propaganda cast on the minds of three generations, including some of the most intelligent people, and its influence continues today.

Relentless Cold War rhetoric accomplished a near total indoctrination of our entire US culture.

Religious institutions, academic and educational institutions from kindergarten through graduate school, professional associations, political associations from local to national, scientific community, economic system, entertainment industry from radio and TV to Hollywood and sports, fraternal organizations, boy scouts, etc.—all systematically colluded and cooperated to preserve unquestioning belief in the unique nobility of the US American system while instilling pathological, rabid, paranoid fear of “enemies”— in our midst as well as “out there”—in order to rationalize otherwise pathologically inexplicable behavior around the world as well as at home.

The atrocities committed in the name of defeating communist bogeymen are nearly beyond belief. As this example shows, our cultural schooling is so pervasive as to generate a universally compelling mythology powerful enough to conceal its own contradictions.

Our cultural corruption was so complete we proudly utilized B-52s blessed by God-fearing chaplains flying five miles high to bomb unarmed, mostly Buddhist peasants living nine thousand miles across the Pacific. It is very difficult to recognize in ourselves what would be considered criminally insane behavior if carried out by others.

Forty years of fanatical “good us versus evil them” leads directly from the 1917 Russian Revolution, the authentic beginning of the Cold War, leading to Korea and Viet Nam.

Prior to 1917, Russia has been a semi-colonial possession of European capital that had settled into typical “Third World” patterns, supplying raw materials to industrial countries while primarily internally developing with foreign capital while experiencing dramatic escalation of debt and impoverishment.

The Russian Revolution was a radical break from western-dominated exploitation, very unacceptable to the capitalist west, the so-called “advanced” industrial countries. It was, in effect, a radical alternative to the way things had been settling in among “moderns” around the non-indigenous global capitalist world.

During Russia’s 1918–1920 Civil War, a number of the allied nations and Japan invaded Russia in efforts to crush socialism.

Winston Churchill, England’s Minister for War and Air (1919–1921), sought desperately “to strangle at its birth” the Bolshevik state. A determined effort by 11 Western nations and Japan to nip the revolution in the bud formed expeditionary forces that invaded Russia in 1918 with nearly nine hundred thousand troops in three regions. Winston Churchill, England’s Minister for War and Air (1919–1921), sought desperately “to strangle at its birth” the Bolshevik state. A determined effort by 11 Western nations and Japan to nip the revolution in the bud formed expeditionary forces that invaded Russia in 1918 with nearly nine hundred thousand troops in three regions.

Archangel in northern Russia, including five thousand US troops; the Odessa region and Crimea in Southern Russia; and Vladivostok in eastern Russia, including seven thousand US troops who remained there until 1920. US casualties during the occupation in northern Russia were nearly 2,900. The State Department told Congress: “All these operations were to offset effects of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia”.

This US intervention into Russia occurred on President Wilson’s orders without a Congressional declaration of war. It also occurred during peace negotiations that had gotten underway on January 4, 1919 in Versailles, France, to formally end the First World War.

The Versailles Treaty was signed June 28, 1919, by Germany and Britain, France, Italy, and Russia, but not by the US.

The intervention into Russia illustrates how terrified the US and the West were of the ideological alternative to capitalism that the Bolsheviks represented.

“High level US planning documents identify the primary threat as ‘radical and nationalistic regimes’ that are responsive to popular pressures for ‘immediate improvement in the low living standards of the masses’ and development for domestic needs, tendencies that conflict with the demand for a ‘political and economic climate conducive to private investment,’ with adequate repatriation of profits and ‘protection of our raw materials.’”

In essence, the Soviet Union was considered a gigantic “rotten apple,” a “challenge . . . to the very survival of the capitalist order.” As Europe was beginning to self-destruct, the US was for the first time becoming a decisive world influence. The Bolshevik revolution, i.e., Communism, was seen as a global enemy that had to be crushed.

The Truman Doctrine Ushers in a National Security State

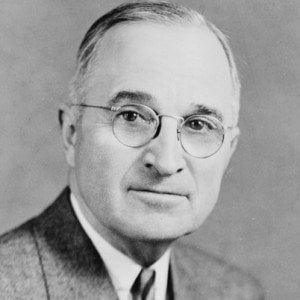

Truman’s March 12, 1947 containment speech, often described as the formal declaration of the Cold War between the Free World and the forces of Communism, helped entrench the idea that the entire world is the specific business of the United States.

Expressing fear of an international Communist threat and marking the beginning of US containment policy, his appeal to congress officially launched the first of thousands of US covert and overt interventions around the world.

Despite Truman’s focus on Greece and Turkey in this speech, internal documents reveal that South Korea was as important, if not more important in terms of needing to be contained. This was made clear in 1949, when both Secretary of State Acheson and the head of State’s policy planning, George Kennan, (image right) concluded that successful suppression by Syngman Rhee of a Korean people’s independence movement would be a key litmus test of the US’s emerging policy of global containment of Communism, despite the Korean’s passion for self-determination. Despite Truman’s focus on Greece and Turkey in this speech, internal documents reveal that South Korea was as important, if not more important in terms of needing to be contained. This was made clear in 1949, when both Secretary of State Acheson and the head of State’s policy planning, George Kennan, (image right) concluded that successful suppression by Syngman Rhee of a Korean people’s independence movement would be a key litmus test of the US’s emerging policy of global containment of Communism, despite the Korean’s passion for self-determination.

Quelling popular self-determination aspirations (autonomy, democracy) around the world became critical for the assurance of continued global Western hegemony. Thus, the Cold War really was a series of hundreds of smaller, but brutal hot wars against popular and revolutionary movements in the “Third World” seeking liberation from historic colonialism (the essential lessons of the Russian Revolution), movements that were essentially supported by the alternative represented by the Soviet Union, in addition to the major post-WWII Third World revolutions in Korea and Viet Nam. In the first, we were stalemated in 1953; the second we lost militarily/politically in 1973, though in each case we decimated and destroyed each culture’s infrastructure while murdering a combined 10 million plus people.

NSC-68: The US, Not the Soviets, Possessed a Global Monolithic Plan

On April 14, 1950, President Truman approved a comprehensive National Security Council study known as NSC 68 (1949-1950). The most fundamental document of the US Cold War, its recommendations began to be implemented on the eve of our hot war in Korea. On April 14, 1950, President Truman approved a comprehensive National Security Council study known as NSC 68 (1949-1950). The most fundamental document of the US Cold War, its recommendations began to be implemented on the eve of our hot war in Korea.

NSC-68 asserted that the US had the unique right and responsibility to impose our chosen “order among nations” so that

“our free society can flourish. . . . Our policy and action . . . must be such to foster a fundamental change in the nature of the Soviet system” and “foster the seeds of destruction within the Soviet system” that will “hasten” its “decay.”

It added,

“The Soviet Union, unlike previous aspirants to hegemony, is animated by a new fanatic faith, antithetical to our own, and seeks to impose its absolute authority over the rest of the world.”

The foundation of the strategy was a “view to fomenting and supporting unrest and revolt in selected satellite countries” and “to reduce the power and influence of the Kremlin inside the Soviet Union.” Any less global imperial policy would have “drastic effects on our belief in ourselves and in our way of life.”

US ability to act had apocalyptic ramifications: “fulfillment or destruction not only of this Republic but of civilization.”

NSC-68 concluded that “the assault on free institutions is world-wide” and “imposes on us, in our own interests, the responsibility of world leadership” such that we must seek “to foster a world environment in which the American system can survive and flourish.” “Any measures, covert or overt, violent or nonviolent” will be called upon as necessary for “frustrating the Kremlin design,” which included “overt psychological warfare” as well as various kinds of “economic warfare.” Utmost care “must be taken to avoid permanently impairing our economy and the fundamental values and institutions inherent in our way of life”.

NSC-68 went on to claim that even “if there were no Soviet Union we would face the great problem of the free society . . . of reconciling order, security . . . with the requirement of freedom.”

The subsequent Korean War was the first time the CIA operated in a hot war. Its arguments became the foundation for tripling the “Defense” budget, stationing troops in Europe, and significantly boosting US conventional and nuclear weapons systems, thus further escalating the arms race.

NSC-68 reveals this incredible irony: Throughout the Cold War years, we were taught to fear the evil Soviets, while our government spent literally trillions of dollars defending our real monolithic plan from their fictional one. Further, the Cold War and its consequent expensive arms race only ensured preservation of an obsessively consumptive Western way of life that is literally destroying life on the planet as we face eco- catastrophe due to global warming. Industrial civilization is an intense heat engine.

Staggering Soviet Losses in WWII Ignored by the West

The US government knew that the Soviet Union was so devastated from the war that it had no capacity or will to imagine or carry out a monolithic plan to control the West. Yet, post -World War II hostility toward the Soviet Union resumed anti-Bolshevik and anti-Communist hatred that had begun in 1917-1918. This, despite the fact, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, that the Soviet armies essentially were responsible for the final defeat of the Nazis in World War II, a war in which the Soviets suffered incredible losses.

A 1994 study published by the Russian Academy of Science estimated USSR casualties at 26.6 million, or 13.5 percent, of its pre WWII war population of 196.7 million.

Before their defeat in 1945, the Nazis had leveled or crippled 15 large Soviet cities, more than 1,700 towns, 70,000 villages, and nearly 100,000 collective farms, while devastating most of its factories, railroads, highways, bridges, and electric power stations. In contrast, the US suffered less than 420,000 deaths, or only three-tenths of a percent of its population, and did not lose any infrastructure.

US Naval Intelligence reported in January 1946 that the USSR was “exhausted . . . not expected to take any action during the next five years which might develop into hostilities with Anglo-Americans.”

Its policies were determined to be defensive in nature, designed only “to establish a Soviet Monroe Doctrine for the area under her shadow, primarily and urgently for security”. Honest historians, academicians, and political leaders knew the basis of Stalin’s insistence on having friendly neighbors and secure borders on its west flank. Unlike the US, the Soviet Union had no oceans to protect it from external aggression.

In 1812, Napoleonic France invaded Russia through Germany. Imperial Japan invaded Siberia in 1906.

Germany invaded Russia in 1914 and again in 1941.

And Poland invaded Russia in 1920 over an old territorial dispute and new ideological fears of Bolshevism.

Thus, Russia’s Western border had been invaded at least four times. George Kennan, architect of the US containment policy, ultimately concluded that

“the image of a Stalinist Russia poised and yearning to attack the West was largely a fiction of the Western imagination.”

He reminded US Americans that the Russian people believed profoundly in “decency, honesty, kindness, and loyalty in the relations between individuals, in fact that the Russians are human beings after all”.

It has been our delusions and arrogance under “God” ever since our own cultural origins in forceful dispossession of hundreds of “strange” Indigenous cultures, both in the Western Hemisphere stealing land and in Africa stealing chattel labor, that we have possessed the cultural DNA of selfishness and narcissism at the expense of others and the Planet Earth. Our Age of stupid and ecocide/suicide is not recognized, as we have depended upon the techniques of denial and the comforting trick of basking in the arrogance of exceptionalism.

And this pattern of US-inflicted atrocities around the globe continues as a bi-partisan political plundering project of Democrats and Republicans, recently accentuated especially since Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump in the 2016 election with the hoax of Russophobia.

This 400-year bestial history of racism, classism, and sexism imposed by primarily White men, on virtually everyone else for 20 generations, was captured perfectly in the 8 minute 46 second video taken by a 17-year-old teenager of a Minneapolis White police officer with the full force of his knee on Black George Floyd’s neck as he tortured, then murdered him.

That knee is on all of our necks now. This has caused more reasons for millions of Whites people to intensely preserve their fantasy of denial.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Brian Willson is a Viet Nam veteran and trained lawyer. He has visited a number of countries examining the effects of US policy. He wrote a psychohistorical memoir, Blood on the Tracks: The Life and Times of S. Brian Willson (PM Press, 2011), and in 2018 wrote Don’t Thank Me for my Service: My Viet Nam Awakening to the Long History of US Lies(Clarity Press). He is featured in a 2016 documentary, Paying the Price for Peace: The Story of S. Brian Willson, and others in the Peace Movement, (Bo Boudart Productions). His web essays: brianwillson.com. He can be reached: [email protected].

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.

Notes

Michael Zezima, Saving Private Power: The Hidden History of the ‘The Good War’ (New York: Soft Skull Press, 2000), 26-7.

Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History (New York: Henry Holt, 1994), 515-516; D. F. Fleming, The Cold War and Its Origins, 1917-1920, Vol I (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1961), 16-35; Howard Zinn, The Twentieth Century: A People’s History (New York: Perennial Library/Harper & Row, 1984), 110-111; David S. Foglesong, America’s Secret War Against Bolshevism: U.S. Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 2-9, 272-3.

National Security Memorandum No. 68 (NSC-68) on “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security” written by a Joint State-Defense Department Committee, under the supervision of Paul Nitze, Director of the Policy Planning Staff, in April 14, 1950, pursuant to the President’s Directive of January 31, 1950.

John Lewis Gaddis, We Know Now: Rethinking Cold War History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 84, 109.

Michael Ellman and S. Maksudov, “Soviet Deaths in the Great Patriotic War: A Note,” Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 46, No. 4, 1994, 671-680.

Harvey Wasserman, America Born & Reborn (New York: Collier Books/Macmillan, 1983), 168; Walter LaFeber, America, Russia, and the Cold war, 1945-1971 (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1972), 14.

Lawrence Wittner, Cold War America (New York: Praeger, 1974), 9; Edward Pessen, Losing Our Souls: The American Experience in the Cold War (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1993), 63; Wasserman, 168.

|