|

Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem “The White Man’s Burden” was published in 1899, during a high tide of British and American rhetoric about bringing the blessings of “civilization and progress” to barbaric non-Western, non-Christian, non-white peoples. In Kipling’s often-quoted phrase, this noble mission required willingness to engage in “savage wars of peace.”

Three savage turn-of-the-century conflicts defined the milieu in which such rhetoric flourished: the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902 in South Africa; the U.S. conquest and occupation of the Philippines initiated in 1899; and the anti-foreign Boxer Uprising in China that provoked intervention by eight foreign nations in 1900.

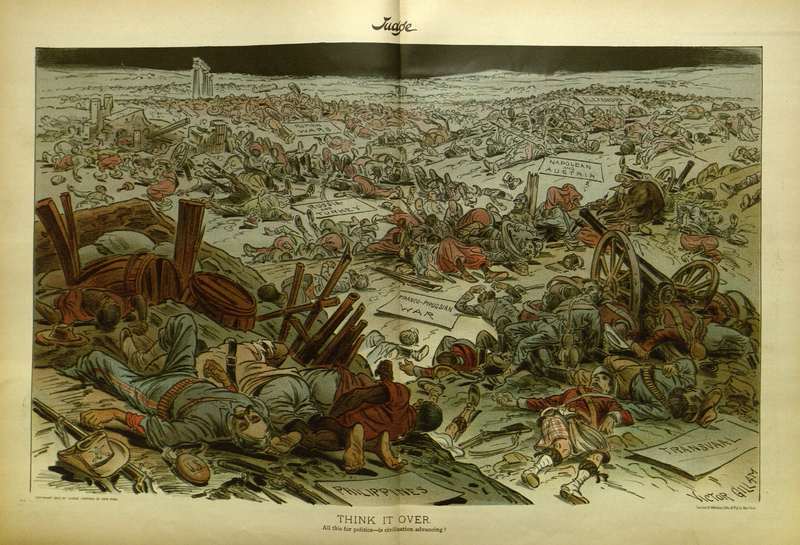

The imperialist rhetoric of “civilization” versus “barbarism” that took root during these years was reinforced in both the United States and England by a small flood of political cartoons—commonly executed in full color and with meticulous attention to detail. Most viewers will probably agree that there is nothing really comparable in the contemporary world of political cartooning to the drafting skill and flamboyance of these single-panel graphics, which appeared in such popular periodicals as Puck and Judge.

This early outburst of what we refer to today as clash-of-civilizations thinking did not go unchallenged, however. The turn of the century also witnessed emergence of articulate anti-imperialist voices worldwide—and this movement had its own powerful wing of incisive graphic artists. In often searing graphics, they challenged the complacent propagandists for Western expansion by addressing (and illustrating) a devastating question about the savage wars of peace. Who, they asked, was the real barbarian?

INTRODUCTION

The march of “civilization” against “barbarism” is a late-19th-century construct that cast imperialist wars as moral crusades. Driven by competition with each other and economic pressures at home, the world’s major powers ventured to ever-distant lands to spread their religion, culture, power, and sources of profits. This unit examines cartoons from the turn-of-the-century visual record that reference civilization and its nemesis—barbarism. In the United States Puck, Judge, and the first version of a pictorial magazine titled Life; in France L’Assiette au Beurre; and in Germany the acerbic Simplicissimus published masterful illustrations that ranged in opinion and style from partisan to thoughtful to gruesome.

In the “civilization” narrative, barbarians were commonly identified as the non-Western, non-white, non-Christian natives of the less-developed nations of the world. Three overlapping turn-of-the-century conflicts in particular stirred the righteous rhetoric of the white imperialists. One was the second Boer War of 1899–1902 that pitted British forces against Dutch-speaking settlers in South Africa and their black supporters. The second was the U.S. conquest and occupation of the Philippines that began in 1899. And the third was the anti-foreign Boxer Uprising in China in 1899–1901, which led to military intervention by no less than eight foreign nations including not only Tsarist Russia and the Western powers, but also Japan.

Civilization and barbarism were vividly portrayed in the visual record. The word “Civilization” (with a capital “C”), alongside “Progress,” was counterposed against the words “barbarism,” “barbarians,” and “barbarity,” with accompanying visual stereotypes. Colossal goddess figures and other national symbols were overwritten with the message on their clothing and the flags they carried.

The archetypal dominance of “Civilization” over “Barbarism” is conveyed in a 1902 Puck graphic with the sweeping white figure of Britannia leading British soldiers and colonists in the Boer War. A band of tribal defenders, whose leader rides a white charger and wields the flag of “Barbarism,” fades in the face of Civilization’s advance. The caption, “From the Cape to Cairo. Though the Process Be Costly, The Road of Progress Must Be Cut,” states that progress must be pursued despite suffering on both sides. The message suggests that the indigenous man will be brought out of ignorance through the inescapable march of progress in the form of Western civilization.

|

“From the Cape to Cairo. Tough the Process Be Costly, The Road of Progress Must Be Cut.” Udo Keppler, Puck, December 10, 1902. Source: Library of Congress

|

In this 1902 cartoon, Britain’s Boer War and goals on the African continent are identified with the march of civilization and progress against barbarism. Brandishing the flag of “Civilization,” Britannia leads white troops and settlers against native forces under the banner of “Barbarism.”

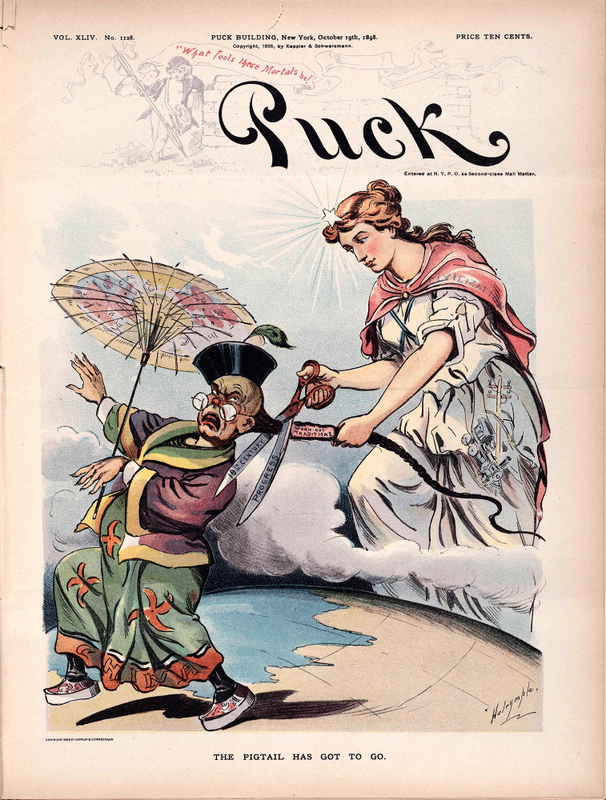

Other graphic techniques were used by cartoonists to communicate this message. For example, the light of civilization literally illuminated vicious, helpless, or clueless barbarians. In “The Pigtail Has Got to Go,” a white-robed goddess wears a star that radiates over a Chinese mandarin. A more earthly approach is taken in the graphic “Some One Must Back Up” that heads this essay. Here the “Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade” shines a headlight upon a raging dragon and sword-wielding Chinese Boxer whose banner reads “400 Million Barbarians.” In the imagery of the civilizing mission, China is portrayed as both backward and savage. The aggressive quest for new markets—China’s millions being the most coveted—was justified as part of the benevolent and inevitable spread of progress.

|

Pro-imperialist cartoons often depicted the West as literally shining the light of civilization and progress on barbaric peoples. In these details, the headlight of a modern vehicle (Judge, 1900) and starlight from a goddess of “civilization” (Puck, 1898) illuminate demeaning caricatures of China. |

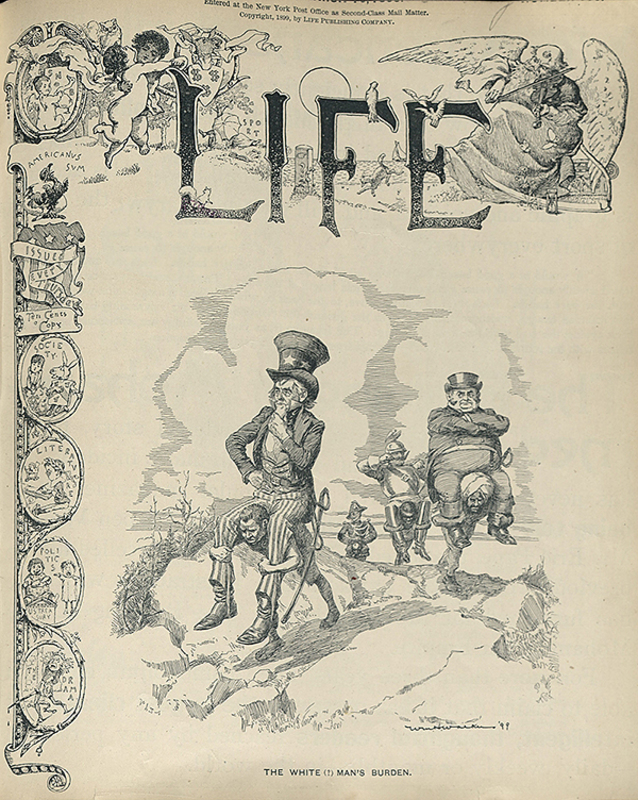

Long-standing personifications and visual symbols for countries were used by cartoonists to dramatize events to suit their message. Anthropomorphizing nations and concepts meant that in an 1899 cartoon captioned “The White Man’s Burden,” the U.S., as Uncle Sam, could be shown trudging after Britain’s John Bull, his Anglo-Saxon partner, carrying non-white nations—depicted in grotesque racist caricatures—uphill from the depths of barbarism to the heights of civilization.

Britain’s John Bull leads Uncle Sam uphill as the two imperialists take up the “White Man’s Burden” in this detail from an overtly racist 1899 cartoon referencing Kipling’s poem.

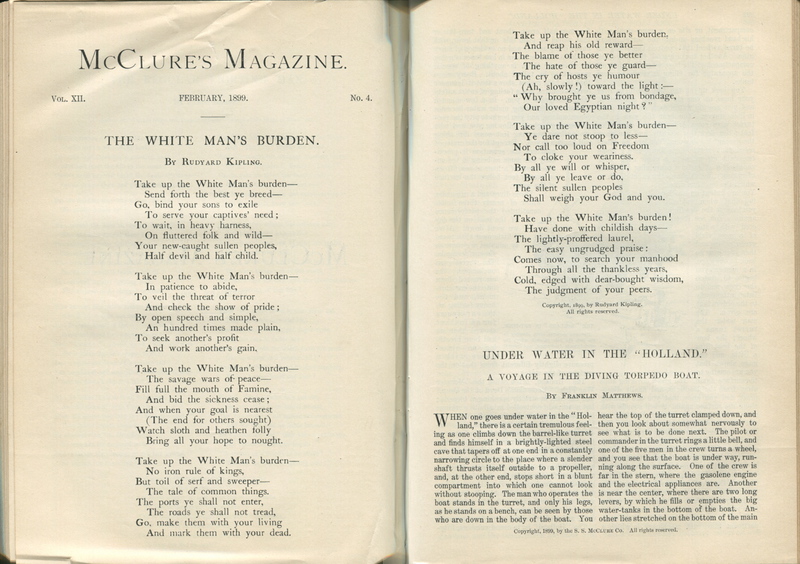

The cartoon takes its title from Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden.” Published in February, 1899 in response to the annexation of the Philippines by the United States, the poem quickly became a famous endorsement of the civilizing mission—a battle cry, full of heroic stoicism and self-sacrifice, offering moral justification for U.S. perseverance in its first major and unexpectedly prolonged overseas war.

|

Original publication of Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “The White Man’s Burden.” McClure’s Magazine, February, 1899 (Vol. XII, No. 4). |

Newly conquered populations, described in the opening stanza as “your new-caught, sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child” would need sustained commitments “to serve your captives‘ needs.”

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

Expansionism promulgated under the banner of civilization could not escape being carried out in global military campaigns, referred to as the “savage wars of peace” in the third stanza:

Take up the White Man’s burden—

The savage wars of peace—

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Such avowed paternalism towards other cultures recast the invasion of their lands as altruistic service to humankind. The aggressors brought progress in the form of modern technology, communications, and Western dress and culture. Christian missionaries often led the way, followed by politicians, troops, and—bringing up the rear—businessmen. Education in the ways of the West completed the political and commercial occupation. Cartoons endorsing imperialist expansion depicted a beneficent West as father, teacher, even Santa Claus—bearing the gifts of progress to benefit poor, backward, and childlike nations destined to become profitable new markets.

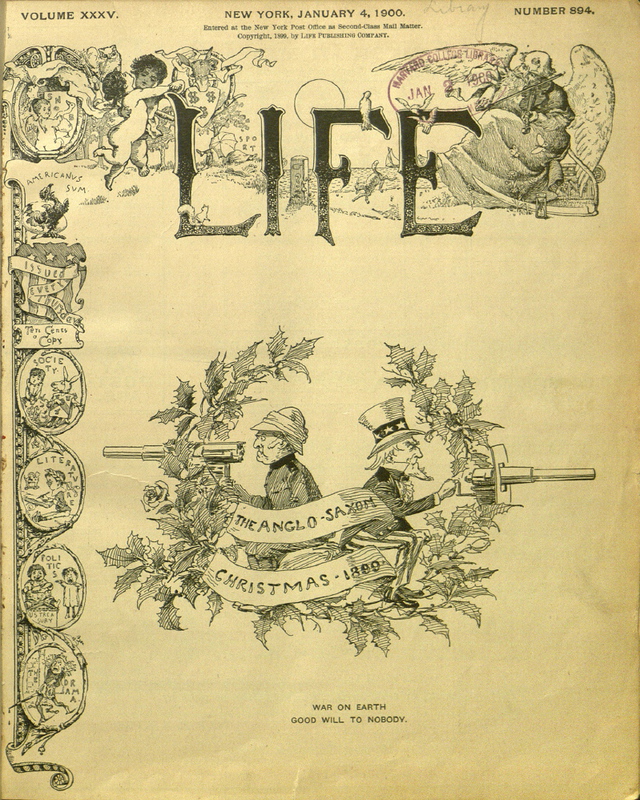

In the United States, the Boer War, conquest of the Philippines, and Boxer Uprising prompted large, detailed, sophisticated, full-color cartoons in Puck and Judge. Although these magazines were affiliated with different political parties—the Democratic Party and Republican Party respectively—both generally supported pro-expansionist policies. Opposing viewpoints usually found expression in simpler but no less powerful black-and-white graphics in other publications. Periodicals likeLife in the U.S. (predecessor to the later famous weekly of the same title), as well as French and German publications, printed both poignant and outraged visual arguments against the imperialist tide, often with acute sensitivity to its racist underpinnings.

These more critical graphics did not exist in a vacuum. On the contrary, they reflected intense debates about “civilization,” “progress,” and “the white man’s burden” that took place on both sides of the Atlantic. It was the anti-imperialist cartoonists, however, who most starkly posed the question: who is the real barbarian?

“THE WHITE MAN’S BURDEN”

During the last decade of the 19th century, the antagonistic relationship between Great Britain and the United States—rooted in colonial rebellion and heightened in territorial conflicts like the War of 1812—grew into a sympathetic partnership. In the U.S., the 1860s Civil War generated suspicion that neutral Britain covertly supported the Confederacy. Postwar industrialization and the introduction of new commodities such as steel and electricity gradually transformed the agrarian nation. As the American West was absorbed and the continent consolidated, the mandate of “Manifest Destiny” shifted from territorial to commercial expansion beyond contiguous borders.

As a long-established world empire, Great Britain held sway over some 12 million square miles and a quarter of the world’s population. Backed by the formidable Royal Navy, Britain could maintain a policy of “splendid isolation” independent of European alliances for much of the century. But by the 1890s, emerging industrial powerhouses like the U.S. and Germany reduced Britain’s industrial dominance. As Britain stepped up financial industries, shipping, and insurance to make up the deficit, global sea power took on additional significance. New commodities also meant advances in weaponry that might give neighboring countries—in particular, Germany—the potential to strike Britain. To maintain its position in the international balance of power, Britain needed allies. Relatively free from European rivalries and well situated to become a transoceanic partner, the U.S. was courted for the role.

Beyond commercial and military prowess, the two nations formed a natural brotherhood within attitudes later labeled as social Darwinism. When applied to people and cultures, the “survival of the fittest” doctrine gave wealthy, technologically-advanced countries not only the right to dominate “backward” nations, but an imperative and duty to bring them into the modern world. The belief in racial/cultural superiority that fueled the British empire embraced the U.S. in Anglo-Saxonism based on common heritage and language. In the U.S., despite spirited resistance from Anglophobic Irish immigrants and anti-imperialist leagues, overseas military campaigns gradually gained public support.

The burgeoning mass media helped promote jingoistic foreign policies by printing disparaging depictions of barbarous-looking natives from countries “benevolently assimilated” by the U.S. A brash Uncle Sam was shown coming under the wing of the older, more experienced empire builder, John Bull. Uncle Sam was portrayed both with youthful energy and as a paternal older figure straining to follow in John Bull’s footsteps as he took up the “White Man’s Burden.”

“After Many Years”: The Great Rapprochement

“The Great Rapprochement” describes a shift in the relationship of the U.S. and Great Britain that, in the 1890s, moved from animosity and suspicion to friendship and cooperation.

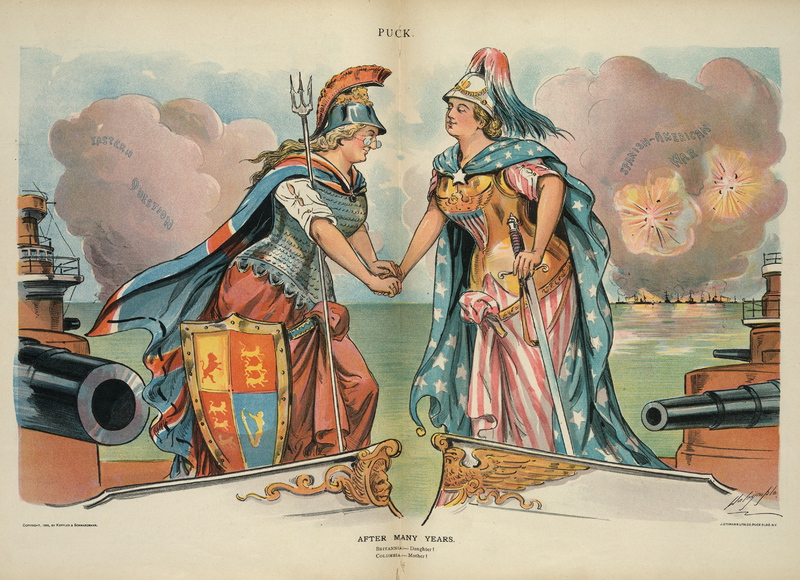

In an 1898 two-page spread in Puck, female symbols of the two nations, Columbia and Britannia, meet as mother and daughter to celebrate their reunion “After Many Years.” Wearing archaic breastplates and helmets, with trident and sword, these outsized, archetypal crusaders helm modern warships. The conspicuously larger size of Britannia’s big guns in Puck’s cartoon reflects England’s leading role in imperial conquest.

Contemporary conflicts are spelled out over dark clouds. Looming on the left, the “Eastern Question” refers to the long-standing British confrontation with Russia in the Balkans that would soon extend to conflict over Britain’s “Cape to Cairo” strategy in Africa. The Battle of Omdurman in September 1898—in which British forces retook the Sudan using Maxim machine guns to inflict disproportionate casualties on native Mahdi forces—was followed almost immediately by the “Fashoda Crisis” with France, in which the British asserted their control of territory around the upper Nile.

Written over the battle clouds on the right, the “Spanish-American War” would have inspired the depiction of Columbia as an emerging military power. On May 1, the U.S. Navy scored its first major victory in foreign waters—far from assured given the weakness of the American fleet at the time—by defeating Spanish warships defending their longtime Pacific colony in the Battle of Manila Bay.

|

“After Many Years. Britannia—Daughter! Columbia—Mother!” Louis Dalrymple, Puck, June 15, 1898. Source: Library of Congress |

In this 1898 cartoon, Britannia (Great Britain) welcomes Columbia (the United States) as an estranged daughter and new imperialist partner. The U.S. entered the elite group of world powers with victories in the “Spanish-American War” (written in the clouds over the naval battle on the right). In the storm clouds on the left, the “Eastern Question” looms.

A poster headlined “A Union in the Interest of Humanity – Civilization, Freedom and Peace for all Time,” probably also dating from 1898, celebrated the rapprochement between the United States and Great Britain with particularly dense detail. In this rendering, progress—economic, technological, and cultural—is spread through global military aggression. The rays of the sun shine over Uncle Sam and John Bull, who clasp hands in a renewed Anglo-American alliance of “Kindred Interests” rooted in the “English Tongue.” Warships on the horizon ground their mission in naval power. Britain, the more powerful military partner, shows celebrated victories over the Spanish Armada in 1588 and over the French and Spanish navies at Trafalgar in 1805. The U.S. is newly victorious in 1898 naval victories over the Spanish at Manila and Santiago de Cuba. “Colonial success” is equated with “chivalry” and “invincibility.”

“A Union in the Interest of Humanity – Civilization. Freedom and Peace for all Time.” ca. 1898, Donaldson Litho Co. Source: Library of Congress “A Union in the Interest of Humanity – Civilization. Freedom and Peace for all Time.” ca. 1898, Donaldson Litho Co. Source: Library of Congress |

This ca. 1898 poster promotes the U.S.-British rapprochement as “A Union in the Interest of Humanity – Civilization, Freedom and Peace for All Time.” Multiple representations symbolize the two Anglo nations: national symbols (the eagle and lion); flags (the Stars and Stripes and Union Jack); female personifications (Columbia and Britannia); male personifications (Uncle Sam and John Bull); and national coats of arms (eagle and shield for America; lion, unicorn, crown, and shield for Great Britain).

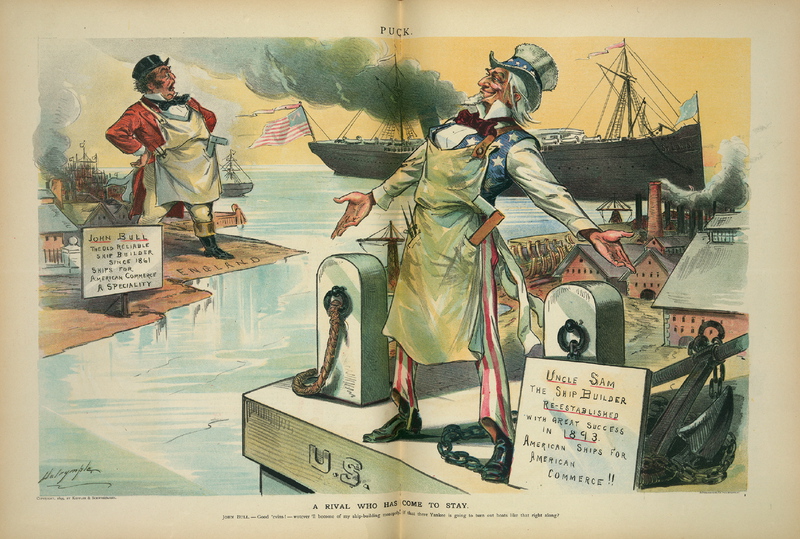

“A Rival Who Has Come to Stay”: Naval Power

In the final years of the Civil War, U.S. naval power was second only to the great seafaring empire of Great Britain. The regular army was dissolved after the war and the ironclad warships gradually fell into disrepair. Few new vessels were commissioned until the 1880s when the first battleships were built, U.S.S. Texas andU.S.S. Maine. Militarily beneath notice by the major European powers, and able to resolve conflicts with Britain in the Western Hemisphere diplomatically, there was little pressure for a strong military in the U.S. With minimal military expenditures, the U.S. economy grew rapidly.

By the 1890s, the U.S. began to revitalize both its commercial and naval fleets. Partnership with Great Britain brought the advantage of shared technology to the U.S., but the new American-made ships represented competition for the British shipbuilding industry. In an 1895 Puck cartoon, “A Rival Who Has Come to Stay,” John Bull gapes while Uncle Sam proudly displays his prowess as “Uncle Sam the Ship Builder.” The U.S. Navy moved up from twelfth to fifth place in the world.

|

“A Rival Who Has Come to Stay. John Bull – Good ‘evins! – wotever ‘ll become of my ship-building monopoly, if that there Yankee is going to turn out boats like that right along?” Louis Dalrymple, Puck, July 24, 1895. Source: Library of Congress

Left: John Bull gapes at a new American steamer. The sign on the shores of England reads, “John Bull – The old reliable ship builder since 1861. Ships for American commerce a speciality.”

Right: Uncle Sam proudly displays his new steamship and a sign that reads, “Uncle Sam the ship builder re-established with great success in 1893. American ships for American commerce!!” |

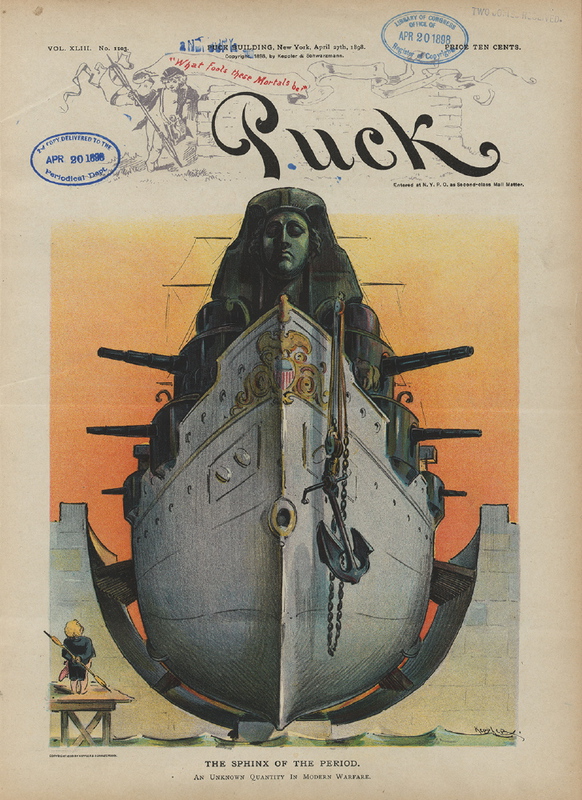

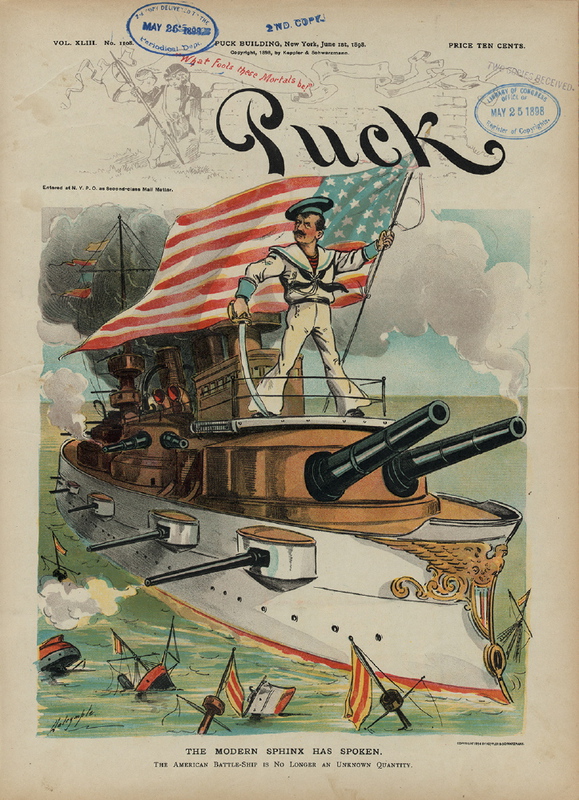

The test of U.S. naval power came with the Spanish-American War. A pair of 1898 graphics offer “before and after” snapshots related to two major events.

On February 15, 1898, the battleship U.S.S. Maine exploded and sank in the harbor at Havana. The Maine had been dispatched to Cuba to support an indigenous insurrection against Spain. The cause of the explosion is still undetermined. In all likelihood, it was an internal malfunction, but many Americans blamed the Spanish and rallied behind the slogan “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain.” The United States declared war on Spain on April 20, and the fury kindled by the sinking of the Maine was appeased by a great U.S. naval victory on the other side of the world two and a half months later. On May 1—a month before the celebratory second magazine cover reproduced here was published—Commodore George Dewey destroyed a Spanish fleet in Manila Bay in the Philippines.

Published in April 27, 1898, the first cartoon calls the monumental warship “The Sphinx of the Period: an unknown quantity in modern warfare.” About a month later, a June 1 graphic picks up on the Sphinx metaphor and declares “The American Battle-Ship is No Longer an Unknown Quantity.” A pugnacious sailor and sweeping U.S. flag have replaced the inscrutable sphinx; guns are smoking, the Spanish fleet lies sunken below.

|

|

| “The Sphinx of the Period. An Unknown Quantity in Modern Warfare.” Udo Keppler, Puck, April 27, 1898. Source: Library of Congress |

“The Modern Sphinx has Spoken. The American Battle-Ship is No Longer an Unknown Quantity.” Louis Dalrymple, Puck, June 1, 1898. Source: Library of Congress |

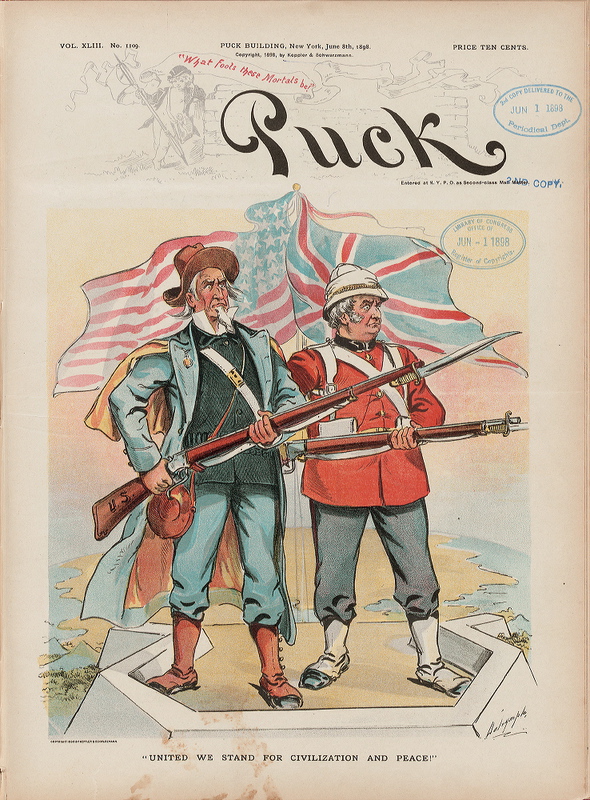

“United We Stand for Civilization and Peace”: the Anglo-Saxon Globe

By the end of 1898, a succession of U.S. military successes and territorial acquisitions reinforced the image of the United States standing side by side with Great Britain in bringing “civilization and peace” to the world. Commodore Dewey’s victory in Manila Bay in May not only paved the way for U.S. conquest of the Philippines, but also provided a valuable naval base for U.S. fleets in the Pacific. (This coincided with the annexation of Hawaii as a U.S. territory in congressional votes in June and July of the same year.) Simultaneously, the war against Spain in Cuba and the Caribbean saw the U.S. seizure of Cuba’s Guantanamo Bay in June, giving the U.S. a naval base retained into the 21st century. This was followed by the invasion and takeover of Puerto Rico. Looming just ahead for the two Anglo nations were turbulence and intervention in such widely dispersed places as Samoa, China, and Africa.

Puck’s cover for June 8, 1898, celebrated this new Anglo-Saxon solidarity and sense of mission with an illustration of two resolute soldiers standing with fixed bayonets on a parapet and overlooking the globe. Their uniforms are oddly reminiscent of the Revolutionary War that had seen them as bitter adversaries a little more than a century earlier. The caption at their feet exclaims “United We Stand for Civilization and Peace!”

|

“’United We Stand for Civilization and Peace!” Louis Dalrymple, Puck, June 8, 1898. Source: Library of Congress

Uncle Sam and John Bull, as fellow soldiers, survey the globe from a parapet. The caption applies the motto “united we stand” to the Anglo-Saxon brotherhood spreading Western civilization abroad. |

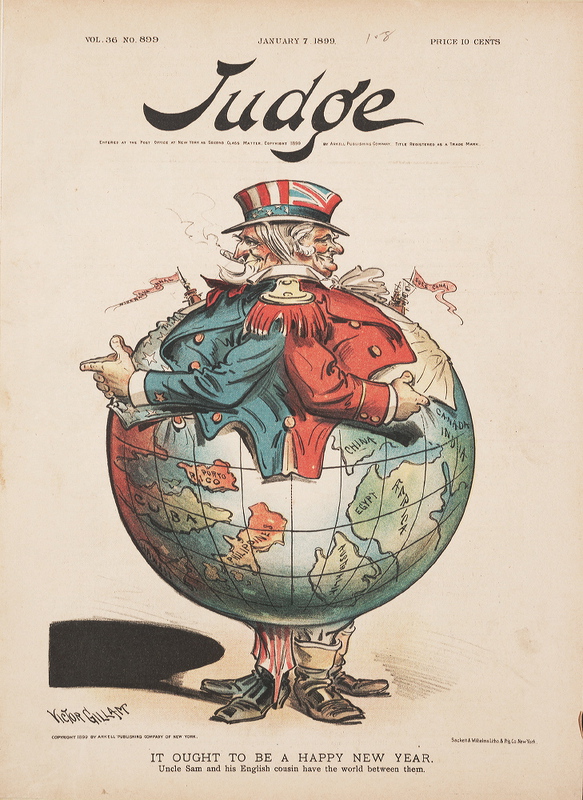

The weekly magazine Judge, a rival to Puck that was published from 1881 to 1947, opened 1899 with a barbed rendering of the Anglo nations gorging on the globe. “It ought to be a Happy New Year,” the caption reads. “Uncle Sam and his English cousin have the world between them.” Here, the United States has ingested Cuba, “Porto” Rico, Hawaii, and the Philippines. Britain is digesting China, Egypt, Australia, Africa, Canada, and India. Warships steam over the horizon of their chests flying banners of great waterways that would ideally open the world to commerce—“Suez Canal” (completed in 1869) and “Managua Canal” (projected through Nicaragua to link the Caribbean and Pacific oceans—an undertaking later transferred to Panama).

|

|

| “It Ought to be a Happy New Year. Uncle Sam and his English cousin have the world between them.” Victor Gillam, Judge, January 7, 1899. Source: CGACGA, The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & MuseumJohn Bull, whose portliness stood for prosperity, has joined with Uncle Sam to swallow the globe. The boats crossing their chests, labeled “Suez Canal” and “Managua Canal,” show the importance of efficient naval and shipping routes through their “distended” realms. The countries have been jumbled to align them with American or British imperialistic interests. |

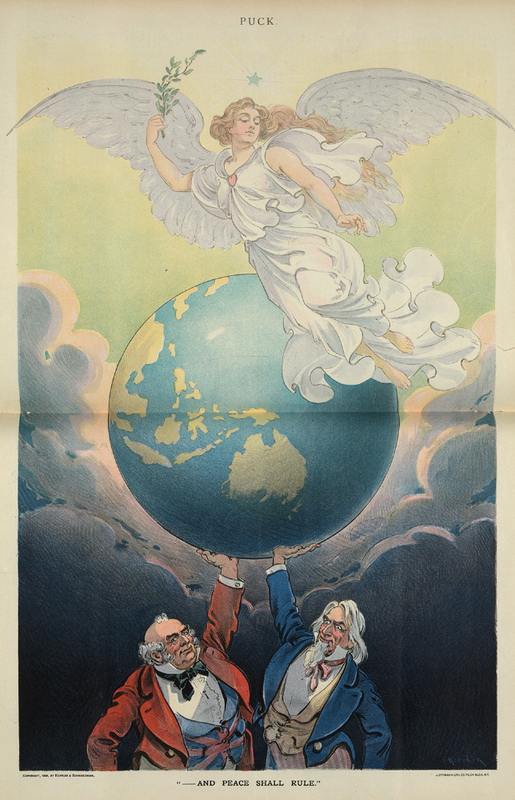

“—And Peace Shall Rule.” Udo Keppler, Puck, May 3, 1899. Source: Library of CongressJohn Bull and Uncle Sam lift the globe, turned toward Asia and the Pacific, to the heavens. The angel of peace and caption suggest that their joint strength will bring about world peace. |

Udo Keppler, a Puck cartoonist who was still in his twenties at the time, was more benign in his rendering of the great rapprochement. A cartoon published in May, 1899 over the caption “—And Peace Shall Rule” offered a female angel of peace flying over a globe (turned to Asia and the Pacific) hoisted by John Bull and Uncle Sam.

From the high to the low, by 1901 the collaboration between the two Anglo nations held a different fate for the globe. In the French cartoon “Leur rêve” (Their dream), the globe is portrayed as a victim carried on a stretcher. The two allies had been embroiled in lengthy wars with costly and devastating effects on the populations in Africa and Asia.

|

“Leur rêve” (Their dream). Théophile Steinlen, L’Assiette au Beurre, June 27, 1901. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

This French cartoon eschews the romantic presentation in the preceding Puckgraphic and casts a far more cynical eye on Anglo-American expansion as fundamentally a matter of conquest. |

In the centerfold of the August 16, 1899 issue of Puck, the not-so-cynical Keppler extended his feminization of global power politics to other great nations including a new arrival on the scene: Japan. Following its victory over China in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, Japan had the heady experience of being welcomed into the imperialist circle. Keppler rendered this as “Japan Makes her Début Under Columbia’s Auspices,” with Columbia, Britannia, and a geisha-like Japan at the center of the scene. Seated around them (left to right) are a feminized Russia, Turkey, Italy, Austria, Spain, and France. A tiny female “China” peers at the scene from behind a wall.

In Library of Congress notes on this image, the seated figure on the left is identified as Minerva—the Roman goddess of wisdom, arts, and commerce. Here, perfectly mythologized, is yet another graphic rendering of the mystique of Western “civilization.”

|

“Japan Makes her Début Under Columbia’s Auspices.” Udo Keppler, Puck, August 16, 1899. Source: Library of Congress

Japan is introduced in this 1899 cartoon as the lone Asian nation in the imperialist circle of world powers. Having defeated China in 1894–95, Japan is presented by Columbia (the U.S.) to her closest ally, Britannia (Great Britain). The feminine representations of imperial nations pictured here include Russia, Turkey, Italy, Austria, Spain, and France. China peeps over the wall. On the left, Minerva, goddess of wisdom and Western civilization, witnesses the debut. |

“Misery Loves Company”: Parallel Colonial Wars (1899-1902)

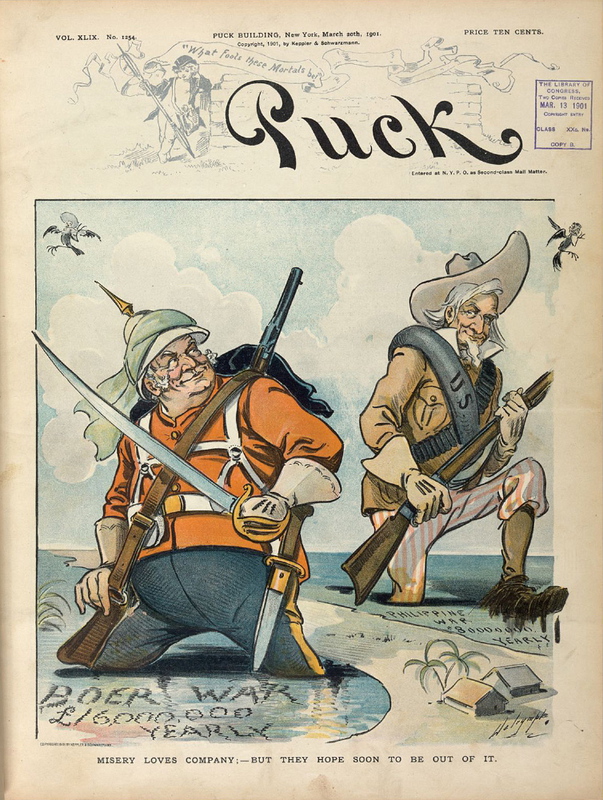

From 1899 to 1902, the U.S. and Great Britain each became mired in colonial wars that were more vicious and long-lasting than expected. Having purchased the Philippines from Spain per the Treaty of Paris for $20 million, the Americans then had to fight Filipino resisters to “benevolent assimilation.” The Philippine-American War dragged on with a large number of Filipino fatalities, shocking Americans unused to foreign wars. The war was declared over by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902 but continued in parts of the country until 1913.

At the same time, Britain was fighting the Anglo-Boer War in South Africa. The war with the Boers (who were ethnically Dutch and Afrikaans-speaking) took place in the South African Republic (Transvaal) and Orange Free State. When rich tracts of gold were discovered, an influx of large numbers of British immigrants threatened to overturn Boer rule over these republics. Britain stepped in to defend the rights of the immigrants, known as uitlanders (foreigners) to the Boers. The larger objective, to gain control of the Boer territories, was part of Britain’s colonial scheme for “Cape to Cairo” hegemony in Africa. The campaign met with fierce resistance and saw the introduction of concentration camps as an extreme maneuver against the Boer defenders.

Despite public neutrality, the U.S. and Britain covertly supported each other. While the European powers favored Spain in the Spanish-American War, for example, neutral Britain backed the U.S. During the 1898 Battle of Manila Bay, British ships quietly reenforced the untried U.S. navy by blocking a squadron of eight German ships positioned to take advantage of the situation. Presence of a German fleet lent evidence to one of the justifications the U.S. gave for war with Spain, that is, to protect the Philippines from takeover by a rival major power. The U.S. policy of “benevolent neutrality” supported Britain in the Boer War with large war loans, exports of military supplies, and diplomatic assistance for British POWs. In addition, the U.S. ignored human rights violations in the use of concentration camps.

The human and financial cost of these extended conflicts was large. A 1901 Puck cover, “Misery Loves Company…,” depicts John Bull and Uncle Sam mired in colonial wars at a steep price: “Boer War £16,000,000 yearly” and “Philippine War $80,000,000 yearly.” Anti-imperialist movements targeted the human rights violations in both the Philippines and Transvaal in their protests.

|

|

| “Misery Loves Company;—but they hope soon to be out of it.” Louis Dalrymple, Puck, March 20, 1901. Source: Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State UniversityBy 1901, John Bull and Uncle Sam were bogged down in prolonged overseas wars at a cost, here, the “Philippine War $80,000,000 yearly” and the “Boer War £16,000,000 yearly.” Yet, the protagonists exchange encouraging looks, revealing the covert support behind their positions of “benevolent neutrality.” |

|

|

| “The Anglo-Saxon Christmas 1899. War on Earth. Good Will to Nobody.” Life, January 4, 1900, Source: Widener Library, Harvard UniversityUnlike Puck and Judge, Life was often highly critical of U.S. overseas expansion. Life’s black-and-white January 4, 1900 cover welcomed the new millennium by illustrating “The Anglo-Saxon Christmas 1899.” John Bull and Uncle Sam are positioned within a holiday wreath, machine guns pointing out in both directions. The caption is ominous: “War on Earth. Good Will to Nobody.” |

The Poet, the President & “The White Man’s Burden”

Rudyard Kipling’s poem that begins with the line “Take up the White Man’s burden—” was published in the United States in the February, 1899 issue of McClure’s Magazine, as the American war against the First Philippine Republic began to escalate. The phrase became a trope in articles and graphics dealing with imperialism and the advancement of Western “civilization” against barbarians—or as the poem put it, “Your new-caught sullen peoples, Half devil and half child.”

The poem acknowledged the thanklessness of a task rewarded with “The blame of those ye better, The hate of those ye guard—” and sentimentalized the “savage wars of peace” as self-sacrificial crusades undertaken for the greater good. Kipling offered moral justification for the bloody war the U.S. was fighting to suppress the independent Philippine regime following Spanish rule. “The White Man’s Burden” was used by both pro- and anti-imperialist factions.

At the core of the “White Man’s Burden” is a reluctant civilizer who takes up arms for “the purpose of relieving grievous wrongs,” in the words of President William McKinley. In his 1898 notes for the Treaty of Paris—which ended the Spanish-American War with Spain surrendering Cuba and ceding territories including Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines—McKinley made a prototypical statement of the civilizer’s responsibilities in the kind of rhetoric still used today:

We took up arms only in obedience to the dictates of humanity and in the fulfillment of high public and moral obligations. We had no design of aggrandizement and no ambition of conquest.

Regarding the Philippines in particular, he continues:

… without any desire or design on our part, the war has brought us new duties and responsibilities which we must meet and discharge as becomes a great nation on whose growth and career from the beginning the ruler of nations has plainly written the high command and pledge of civilization.

McKinley also mentions profit, free trade, and the open door in Asia:

Incidental to our tenure in the Philippines is the commercial opportunity to which American statesmanship cannot be indifferent. It is just to use every legitimate means for the enlargement of American trade; but we seek no advantages in the Orient which are not common to all. Asking only the open door for ourselves, we are ready to accord the open door to others.

An exceptionally vivid cartoon version of Kipling’s message titled “The White Man’s Burden (Apologies to Rudyard Kipling)” was published in Judge on April 1, 1899. “Barbarism” lies at the base of the mountain to be climbed by Uncle Sam and John Bull—with “civilization” far off at the hoped-for end of the journey, where a glowing figure proffers “education” and “liberty.” The fifth stanza of Kipling’s poem refers to an ascent toward the light:

The cry of hosts ye humour

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light:—

“Why brought he us from bondage,

Our loved Egyptian night?”

Barbarism’s companion attributes of backwardness, spelled out on the boulders underfoot, include oppression, brutality, vice, cannibalism, slavery, and cruelty. Britain leads the way in this harsh rendering, shouldering the burden of “China,” “India,” “Egypt,” and “Soudan.” The United States staggers behind carrying grotesque racist caricatures labeled “Filipino,” “Porto Rico,” “Cuba,” “Samoa,” and “Hawaii.”

The racism and contempt for non-Western others that undergirds Kipling’s famous poem—and the “civilizing mission” in general—is unmistakable here. At the same time, the distinction the artist draws between Britain’s burden and America’s is striking. America’s recent subjugated populations are savage, unruly, and rebellious—literally visually “half devil and half child,” as Kipling would have it. By contrast, with the exception of Sudan, the burden Britain bears reflects backward older cultures that look forward to “civilization” or back, condescendingly, at those people, cultures, and societies deemed even closer than they to “barbarism.” Both visually and textually, the “white man’s burden” was steeped in derision of non-white, non-Western, non-Christian others.

|

|

The U.S. follows Britain’s imperial lead carrying people from “Barbarism” at the base of the hill to “Civilization” at its summit. In this blatantly racist rendering, America’s newly subjugated people appear far more primitive and barbaric than the older empire’s load.

Shortly after Kipling’s poem appeared, the consistently anti-imperialist Life fired back with a decidedly different view of the white man’s burden on its March 16, 1899 cover: a cartoon that showed the foreign powers riding on the backs of their colonial subjects. The black-and-white drawing by William H. Walker captured the harsh reality behind the ideal of benevolent assimilation, depicting imperialists Uncle Sam, John Bull, Kaiser Wilhelm, and, coming into view, a figure that probably represents France, as burdens carried by vanquished non-white peoples. The addition of an exclamation point in the caption, “The White (!) Man’s Burden,” emphasized its hypocrisy. The U.S. appears to be carried by the Philippines, Great Britain by India, and Germany by Africa. Although Wilhelm II was famous for introducing the concept of a “yellow peril,” Germany’s major colonial possessions were in Africa.

|

“The White (!) Man’s Burden” William H. Walker, cover illustration, Life, March 16, 1899. Source: William H. Walker Cartoon Collection, Princeton University Library

An exclamation point was added to the phrase, “The White (!) Man’s Burden,” in the caption to this Life cover published shortly after Kipling’s poem. Imperialists Uncle Sam, John Bull, Kaiser Wilhelm, and, in the distance, probably France are borne on the backs of subjugated people in the Philippines, India, and Africa. |

PROGRESS & PROFITS

“Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade”: the Asia Market

Civilization and trade went hand in hand in turn-of-the-century imperialism. Progress was promoted as an unassailable value that would bring the world’s barbarians into modern times for their own good and the good of global commerce. As the U.S. moved into the Pacific, “China’s millions” represented an enticing new market, but the eruption of the anti-Christian, anti-foreign Boxer movement threatened the civilizing mission there.

In a striking Judge graphic, an “Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade” lights a pathway through the darkness, leading with a gun and the message: “Force if Necessary.” Overladen with manufactured goods and modern technology, the vehicle is driven by a resolute Uncle Sam. Blocking its uphill path, the Chinese dragon crawls downhill bearing a “Boxer” waving a bloody sword and banner reading “400 Million Barbarians.” The image puts progress and primitivism on a collision course at the edge of a cliff. Fears that China would descend into chaos and xenophobia justified intervention to safeguard the spread of modernity, civilization, and trade. The image argues that a crisis point has been reached and the caption states, “Some One Must Back Up.”

|

“Some One Must Back Up.” Victor Gillam, Judge, December 8, 1900. Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

Left: “Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade”, “Progress”, “Force if Necessary”, “Cotton” “Dry Goods” “Education”

Right: “Boxer”, “400 Million Barbarians”, “China”

Civilization and barbarism meet as the headlight of Uncle Sam’s gun-mounted “Auto-Truck of Civilization and Trade” shines the light of “Progress” on “China.” Published during the Boxer uprisings against Westerners and Christians, the cartoon portrays China as a frenzied dragon under the control of a “Boxer” gripping a bloody sword and banner reading “400 Million Barbarians.” In the balance of power between technological “progress” and primitive “barbarians,” the cartoon makes clear who “must back up.” |

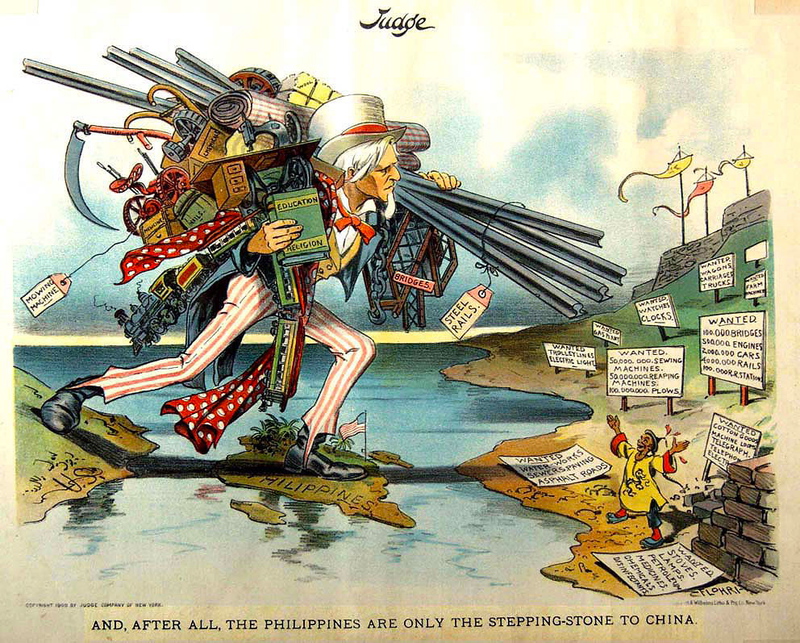

The link between U.S. conquest of the Philippines and the lure of the China market was widely acknowledged at the time, and no one rendered this more vividly, concisely, and admiringly than the cartoonist Emil Flohri. One cannot imagine a blunter caption than the one that accompanied his 1900 cartoon for Judge: “And, after all, the Philippines Are Only the Stepping-Stone to China.” In Flohri’s image, Uncle Sam—heavily laden with steel, railroads, bridges, farm equipment, and the like—gives a cursory nod to the spread of civilization by grasping a book titled “Education” and “Religion.” The confident giant is greeted with open arms by a diminutive yellow-clad Chinese mandarin.

Anticipated U.S. exports appear on signs that advertise the rich market awaiting American manufacturers. Each sign is topped by the word “Wanted” and the goods listed include trolley lines, electric lights, water-works, sewers, paving, asphalt roads, watches, clocks, wagons, carriages, trucks, 100,000 bridges, 500,000 engines, 2 million cars, 4 million rails, 100,000 RR stations, cotton goods, telegraph, telephone, stoves, lamps, petroleum, medicines, chemicals, disinfectants, 50 million reaping machines, 100 million plows, and 50 million sewing machines.

|

“And, After All, the Philippines are Only the Stepping-Stone to China.” Emil Flohri, Judge, ca. 1900. Source: Wikimedia

The Philippines are diminished as “Only the Stepping-Stone” that enables the U.S. to reach the eagerly anticipated China market. Along with his burden of steel, trains, sewing machines, and other industrial goods, Uncle Sam carries a book titled “Education, Religion” in a nod to the rhetoric of moral uplift that accompanied the commercial goals of the civilizing mission. He is greeted with open arms by a mandarin and “Wanted…” signs articulating prodigious opportunities for business. |

Commercial interests not only drove U.S. policy in Asia, but also shaped public opinion about it. The artist George Benjamin Luts offered an exceptionally scathing rendering of the linkage of conquest, commerce, and censorship in an 1899 cartoon titled “The Way We Get the War News: The Manila Correspondent and the McKinley Censorship.” Published in a short-lived radical periodical, The Verdict, the cartoon shows a war correspondent in chains, writing his story under the direction of military brass. Business and government colluded with the military in silencing press coverage of the poor conditions suffered by American soldiers, including scandals around tainted supplies, and the grim realities of the Philippine-American War itself—censorship that foreshadowed the broader excising of the unpleasant war from national memory. Robert L. Gambone in his 2009 book, Life on the Press: The Popular Art and Illustrations of George Benjamin Luks, describes the cartoon as follows:

…The Way We Get Our War News (The Verdict, August 21, 1899, front cover) excoriates military press censorship, a supremely ironic development given the appeals to freedom used to justify the war. Within a barred room, its walls painted blood-red, a cohort of five army officers headed by a sword-wielding Major General Elwell Stephen Otis (1838-1909), military governor of the Philippines, forces a manacled war correspondent to write only approved dispatches. A mound of scribbled papers from an overflowing wastebasket testifies to the coercion exerted upon him to induce cooperation. [p. 199]

|

“The Way We Get the War News. The Manila Correspondent and the McKinley Censorship.” George Benjamin Luts, The Verdict, August 21, 1899. Source: Houghton Library, Harvard University |

A chained “War Correspondent” is forced to rewrite his reports under the direction of Major General Elwell Otis during the Philippine-American War. As the military governor until May 1900, Otis inflated Filipino atrocities and prevented journalists, Red Cross officials, and soldiers from reporting American atrocities, though ghastly accounts slipped through. The cartoonist targets capitalists as the true power behind the policies and practices in the Pacific, with a portrait of businessman Marcus Hanna—a dollar sign elongating his ear—that dwarfs a portrait of President William McKinley.

In the background, the artist placed a large portrait of a large man, Marcus Hanna, next to a miniature of President William McKinley to show their relative influence on policy. Hanna was a wealthy businessman with investments in coal and iron who financed McKinley’s 1896 election campaign with record-breaking fundraising that led to the defeat of opponent William Jennings Bryan. (In the 1900 elections, Bryan ran on an anti-imperialist platform and was again defeated by McKinley.) Gambone described the portraits as, “a testament to the weakness of McKinley, the overarching power of Hanna, and the Trust interests that supported expansion of American business into the Pacific.”

The foothold in the Philippines brought China within reach. As the golden goose, China’s perceived mass market was to be protected for free trade against takeover by increasingly assertive foreign powers. Boxer attacks on Western infrastructure and the siege of foreign diplomats in Beijing gave the international powers a pretext for entering China with military force. Though “carving the Chinese melon” was a popular metaphor, none of the invaders seriously considered partitioning the large country under foreign rule. (The exception would be Manchuria, alternating between Russian and Japanese control in the coming years.) But rivalries for commercial privileges never abated even when an eight-nation Allied military force was forged between the world powers in the summer of 1900.

In the West, China was often characterized as befuddled and archaic under the rule of an inscrutable crone, the Empress Dowager. In Puck’s October 19, 1898 cover, “Civilization” holds “China” by his queue, labeled “Worn Out Traditions,” ready to cut it off with the shears of “19th Century Progress.” The helpless mandarin tries to run away. It was feared that the mystical rituals and xenophobic violence of the Yi He Tuan (Boxer) secret society would overwhelm China’s ineffectual rulers, cast the country into chaos, and hinder the trade and profits anticipated by the great powers.

|

“The Pigtail Has Got to Go.” Louis Dalrymple, Puck, October 19, 1898. Source: Beinecke Rare Books & Manuscripts, Yale University |

A white, feminine personification of “Civilization” (written on her cloak) radiates light over the aged figure of “China” (written on his hem) running away and shielding himself with a parasol. Civilization and progress are inseparable, a train and telegraph drawn in her robes. China’s “Worn Out Traditions”—represented by the queue hairstyle required during the Qing dynasty—are about to be cut with the shears of “19th Century Progress.”

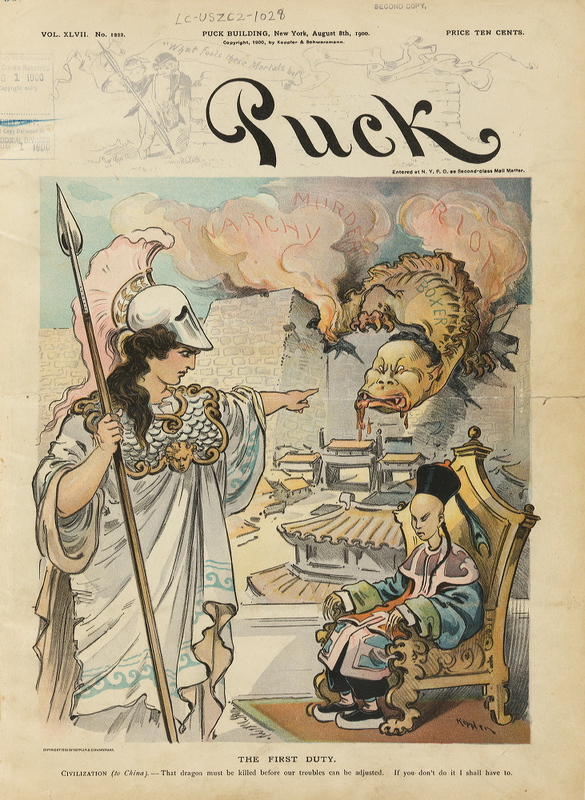

Nearly two years later, in the midst of the Boxer Uprising, Puck was still resorting to the same sort of stereotyped juxtaposition. On the magazine’s cover for August 8, 1900, the familiar feminized and godlike personification of the West points at a slavering dragon, labeled “Boxer,” crawling over the wall of the capital city. Now clad in armor and carrying a spear, she threatens to intervene to stop the anti-foreign, anti-Christian acts of “anarchy, “murder,” and “riot” that have spread to Beijing. China’s hapless young Manchu emperor, traditionally and exotically robed, sits passively in the foreground. The caption, titled “The First Duty,” carries this subtitle: “Civilization (to China)—That dragon must be killed before our troubles can be adjusted. If you don’t do it I shall have to.”

|

“The First Duty. Civilization (to China). — That dragon must be killed before our troubles can be adjusted. If you don’t do it I shall have to.” Udo Keppler, Puck, August 8, 1900. Source: Library of Congress |

“Civilization” warns China’s passive emperor to stop the “Anarchy,” “Murder,” and “Riot” spread by Boxer insurgents—visualized as a dragon crawling over the city wall—attacking missionaries, Chinese Christians, and Westerners. When this cartoon was published, the foreign Legation Quarter in Beijing was besieged by Boxers and Qing troops. Lasting from June 20 to August 14, 1900, the siege was the catalyst for a rescue mission by the Allied forces of eight major world powers.

“School Begins”: Unfit for Self-Rule

Invading foreign lands was a relatively new experience for the U.S. Given the rhetoric of civilizing uplift used to justify expansion, training was expected as part of the incorporation of new territories into the U.S. Uneasiness over the idea of using force to govern a country was overcome by tracing the issue of consent back through recent history. An elaborate Puck graphic from early in 1899 called “School Begins” incorporates all the players in a classroom scene to illustrate the legitimacy of governing without consent. In the caption, Uncle Sam lectures: “(to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you’ve got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!”

The blackboard contains the lessons learned from Great Britain on how to govern a colony and bring them into the civilized world, stating, “… By not waiting for their consent she has greatly advanced the world’s civilization. — The U.S. must govern its new territories with or without their consent until they can govern themselves.” Veneration of Britain’s treatment of colonies as a positive model attests to the significant shift in the American world view given U.S. origins in relation to the mother country. Even the Civil War is referenced, in a wall plaque: “The Confederate States refused their consent to be governed; but the Union was preserved without their consent.” Refuting the right of indigenous rule was based on demonstrating a population’s lack of preparation for self-governance.

The image exhibits a racist hierarchy that places a dominant white American male in the center, and on the fringes, an African-American washing the windows and Native-American reading a primer upside down. China, shown gripping a schoolbook in the doorway, has not yet entered the scene. Girls are part of the obedient older class studying books labeled “California, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.” The only non-white student in the older group holds the book titled “Alaska” and is neatly coifed in contrast to the unruly new class made up of the “Philippines, Hawaii, Porto Rico, and Cuba.” All are depicted as dark-skinned and childish.

|

“School Begins.” Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you’ve got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!” Louis Dalrymple, Puck, January 25, 1899. Source: Beinecke Rare Books & Manuscripts, Yale University |

Louis Dalrymple’s exceptionally detailed 1899 Puck graphic includes racist and denigrating depictions within a schoolhouse metaphor to demonstrate the right to govern newly acquired territories without their consent. The argument follows England’s example, as spelled out on the blackboard, that “By not waiting for their consent, she has greatly advanced the world’s civilization.” “An African-American washes windows.” The book on the desk reads: “U.S. First Lessons in Self Government.” The paper on desk reads: “The New Class. Philippines, Hawaii, Cuba, Porto Rico.” A Native American reads a book upside down and a prospective Chinese pupil stands in the doorway.

The wall sign overhead reads: “The Confederate States refused their consent to be governed; but the Union was preserved without their consent.” The class holds schoolbooks labeled “Alaska, Texas, Arizona, California, New Mexico.” Blackboard text: “The consent of the governed is a good thing in theory, but very rare in fact. England has governed her colonies whether they consented or not. By not waiting for their consent she has greatly advanced the world’s civilization. — The U.S. must govern its new territories with or without their consent until they can govern themselves.”

Harper’s Weekly later echoed the classroom scene with a cover captioned “Uncle Sam’s New Class in the Art of Self-Government.” The class is disrupted by revolutionaries from the new U.S. territories of the Philippines and Cuba, whose vicious fight brands them as barbarously unfit for self-rule. Model students Hawaii and “Porto” Rico appear as docile girls learning their lessons. The backdrop to the scene, a large “Map of the United States and Neighboring Countries,” attests to the new position the U.S. has taken in the world, with its overseas territories marked by U.S. flags.

Uncle Sam breaks up a fight between students identified as “Cuban Ex-Patriot” and “Guerilla” in his “New Class in the Art of Self-Government.” The famous white-haired general, Máximo Gómez, a master of insurgency tactics in the Cuban Independence War (1895–1898) reads a book with his name on it. The president of the First Philippine Republic, Emilio Aguinaldo, is portrayed as a barefoot savage, wild hair escaping from a dunce cap. “Hawaii” and “Porto Rico” are model female students. The large “Map of the United States and Neighboring Countries” is dotted with U.S. flags marking newly-acquired territories.

In its final issue for 1899—a time when the U.S. suppression of Filipino resistance was at its peak—Puck turned to a feel-good holiday graphic to reaffirm this theme of the bounty promised to newly invaded countries and peoples. Columbia and Uncle Sam pluck gifts from “Our Christmas Tree,” including law and order, technology, and education, for overseas territories “Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines,” condescendingly drawn as grateful children.

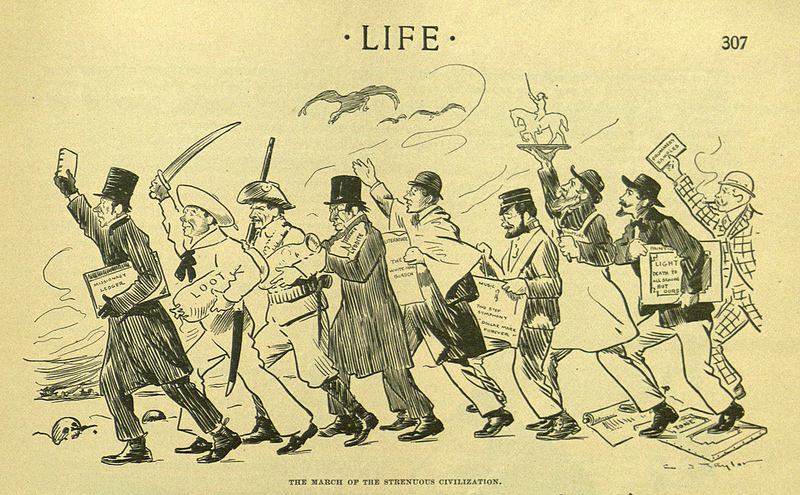

The laudatory rhetoric and imagery of a “white man’s burden” and “civilizing mission” received a sharp rejoinder in a cartoon published by Life in April, 1901 under the title “March of the Strenuous Civilization.” In this sardonic rendering of the realities of imperialist expansion, a missionary leads the charge holding a “Missionary Ledger.” Immediately behind him march a sword-brandishing sailor carrying “loot” and a rifle-bearing soldier carrying “booty.” “Science” comes next, clutching “lyddite,” a high explosive first used by the British in the Boer War. “Literature” follows, holding the text of Kipling’s poem, “The White Man’s Burden.” Music plays an organ labeled “Two Step Symphony—‘Dollar Mark Forever.’” Behind Music comes “Sculpture,” holding up a monument to a war hero. “Painting” carried a portfolio inscribed “‘Light. Death to all Schools but Ours.” The last marcher holds up “Drummer’s Samples,” referring to the traveling salesmen of business and commerce.

Skulls dot the landscape ahead in Life’s grim rendering. Vultures hover above the procession, and the artifacts of past civilization are trampled underfoot at the rear. Life’s satire of the “white man’s burden” mystique offers a procession of the supporters of the new imperialism beginning with missionaries and ending with the traveling salesman.

|

“The March of the Strenuous Civilization.” C. S. Taylor, Life, April 11, 1901. Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

|

Life’s satire of the “white man’s burden” mystique offers a procession of the supporters of the new imperialism beginning with missionaries and ending with the traveling salesman.

Even the language of Life’s caption is subversive, for it picks up a famous pro-imperialist speech by Theodore Roosevelt titled “The Strenuous Life.” Delivered on April 10, 1899, two years before Roosevelt became president, the most famous lines of the speech were these:

I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger …

… So, if we do our duty aright in the Philippines, we will add to that national renown which is the highest and finest part of national life, will greatly benefit the people of the Philippine Islands, and, above all, we will play our part well in the great work of uplifting mankind.

BIBLES & GUNS

“Advance Agent of Modern Civilization”: Religion & Empire

Religion played a major role in the characterization of others as heathens in need of salvation through education, conversion, and civilizing in the ways of Christian culture. The violence applied to these aims both in bodily harm and cultural ruin was only part of the hypocrisy. A number of critical cartoons of the time addressed the unsavory behavior of the “civilizers” themselves, and the disparity between doctrine and actions.

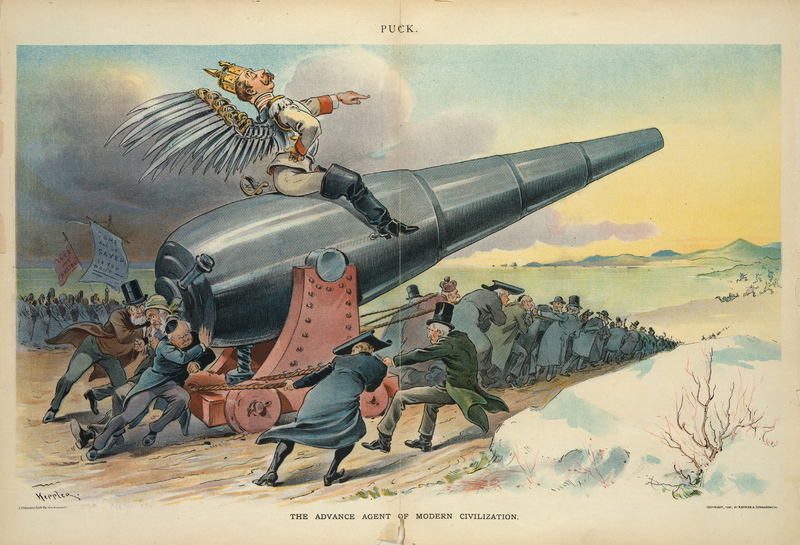

The synergy of piousness and power is the subject of a Keppler cartoon, “The Advance Agent of Modern Civilization,” in the January 12, 1898, issue of Puck. The divine right of kings—here, Wilhelm II, Emperor of Germany as a pompous war lord mounted on a colossal cannon—is intermingled with the divine mission of clergy, often the first Westerners allowed into foreign lands. The penetration of missionaries into the interior of China, for example, destabilized rural economies and incited anti-foreign sentiments. The cartoon links might with right, as the cannon is pushed and dragged forward by clergy identified by their headgear: skullcap, biretta, clerical hat, top hat, and distinctive English-style shovel hat. Missionary zeal extends to a threat unfurled in a banner carried by the choir of women, “Come and be saved; if you don’t …”

|

“The Advance Agent of Modern Civilization.” Udo Keppler, Puck, January 12, 1898. Source: Library of Congress

|

Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II appears as an anointed leader, his angel wings made of swords, astride a cannon dragged by clerics and missionaries toward foreign lands. Wilhelm points ahead, where the inhabitants flee.

In a post-Bismarck era, Germany was a late-comer to the colonial land grab in Africa and the Pacific. Its colonies were acquired through purchase, agreements with other world powers, and economic domination. However, brutally repressive policies followed that included accusations of genocide. Cartoonists portrayed Wilhelm II with increasing venom as a perpetrator of violence through World War I. He was just one of the imperial rulers and national figures to be demonized. As these cartoons reflect, the U.S., itself a new colonial power, was particularly threatened by the rise of Germany as a rival in the Pacific. Puck’s caricature of Germany’s Bible-quoting Kaiser Wilhelm II ready to machine gun foreign non-believers captures the role of Christianity in turn-of-the-century Western imperialism.

|

|

|

| “The Gospel According to St. William.” Udo Keppler, Puck, September 26, 1900. Source: Library of Congress |

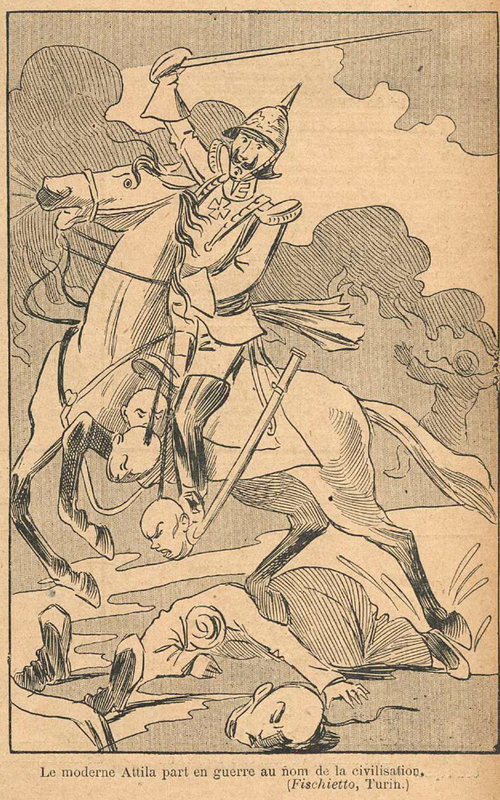

“Le moderne Attila part en guerre au nom de la civilisation” (The modern Attila goes to war on behalf of civilization). Fischietto, ca. 1900. |

An Italian cartoonist who drew William II as a modern “Attila” beheading Chinese foes was likely inspired by his “Hun” speech to German soldiers shipping out to fight in the Boxer Uprising in China, delivered on July 27, 1900, in which he called for total war:

Should you encounter the enemy, he will be defeated! No quarter will be given! Prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands is forfeited. Just as a thousand years ago the Huns under their King Attila made a name for themselves, one that even today makes them seem mighty in history and legend, may the name German be affirmed by you in such a way in China that no Chinese will ever again dare to look cross-eyed at a German.

“As the Heathen See Us”: Reversing the Gaze

Although usually associated with the pro-expansionist proponents of “civilization” and “progress,” Puck on occasion turned a discerning eye on the double standards of America’s so-called noble mission in the Philippines and China. Vignette-style graphics placed an array of smaller scenes around the central image. Several of these graphics from Puck commented on America’s problems at home while accusing “others” of being barbarians.

“Our ‘Civilized’ Heathen” asks what is civilized and who are the heathen. Ugly and shocking scenes of violence in 19th-century American life are ironically captioned as “refined and elegant” to challenge the self-image of a nation contributing cash “to save the heathen of foreign lands” while ignoring its own barbarity.

|

“Our ‘Civilized’ Heathen. And yet Uncle Sam is always giving money to ‘save the Heathen.’” Samuel D. Ehrhart, Puck, September 8, 1897. Source: Library of Congress

|

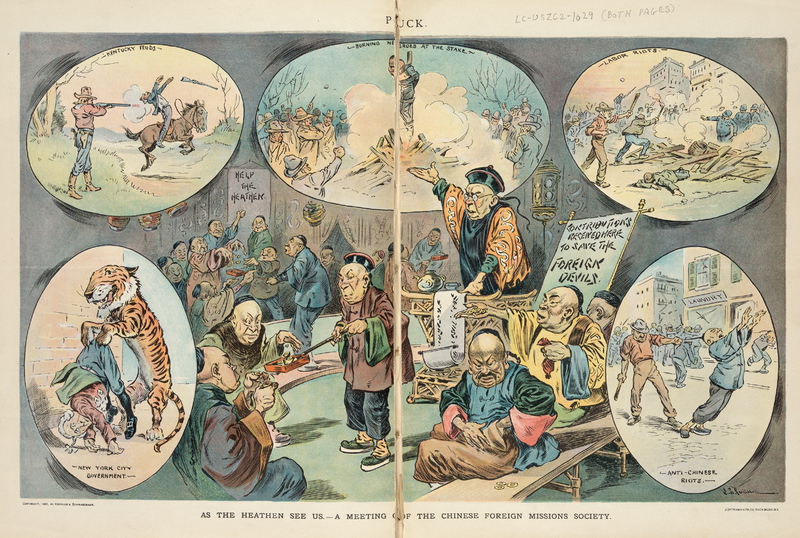

Raising money to “Save the Foreign Devils” recurs in the visual record. Cartoonist Victor Gillam turns the tables on American missionary zeal and moral imperative to “save the heathen” by showing how the Chinese might view the “foreign devils” in vignettes of ignorance, racism, and extreme violence in the United States.

|

“As the Heathen See Us — A Meeting of the Chinese Foreign Missions Society.” John S. Pughe, Puck, November 21, 1900. Source: Library of Congress

|

| Left: “Kentucky feuds”, “New York City Government” |

Center: “Burning Negros at the Stake” |

Right: “Labor riots”, “Anti-Chinese Riots” |

Violence in the Name of Peace and Civilization

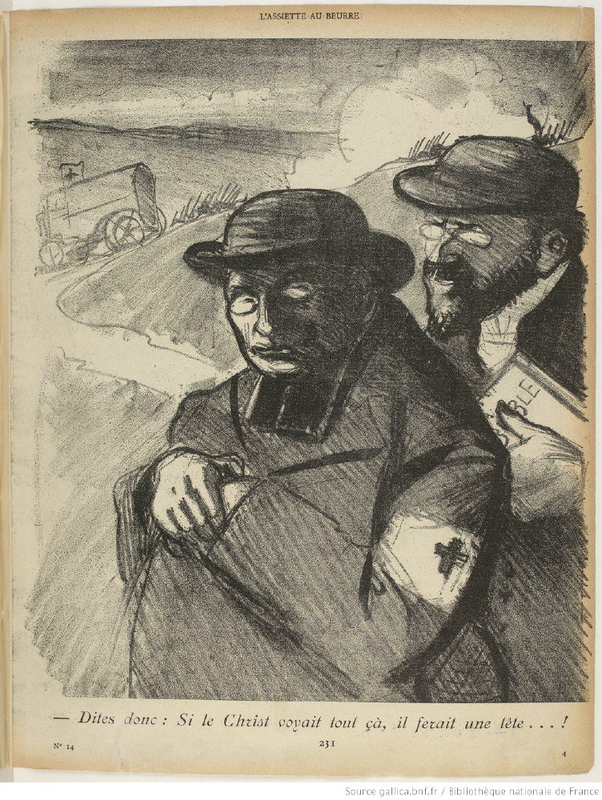

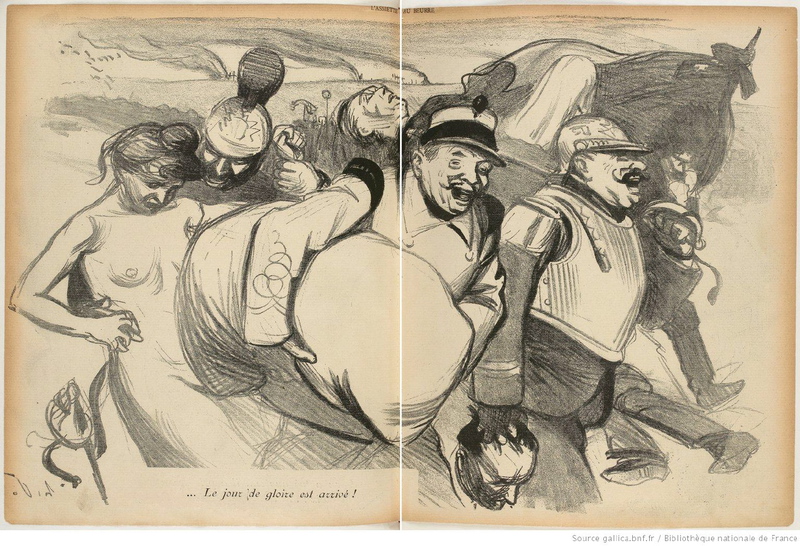

The eight-nation military intervention during the Boxer Uprising in China in 1900 amounted to a global case study of how nations with superior technology wreaked violence abroad in the name of bringing about peace and civilization. In a run of 13 lithographs published in the July 4, 1900 issue of the French periodical L’Assiette au Beurre, the cartoonist René Georges Hermann-Paul was especially incisive in calling attention to this grim reality.

|

|

|

| “— Dites donc: Si le Christ voyait tout ça, il ferait une tête …!” I’d say: If Christ saw all this, he would lose his mind …! |

“… Le jour de glorie est arrivé!” The day of glory has come! |

“— Personne ne comprend ce qu’il dit, mon commandant. — Parfait, fusillez-le.” “No one understands what he says, my commander” “Fine, shoot him.” |

| René Georges Hermann-Paul, L’Assiette au Buerre, No. 14, July 4, 1901. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France |

In this French cartoon from a special issue titled, “La Guerre” (War), a missionary and a Red Cross representative lament the violent and un-Christian behavior of Westerners overseas. Additional images from the issue depict barbaric behavior by the multinational force that intervened in China during the Boxer Uprising. The graphics include pillage, rape, and wanton executions.

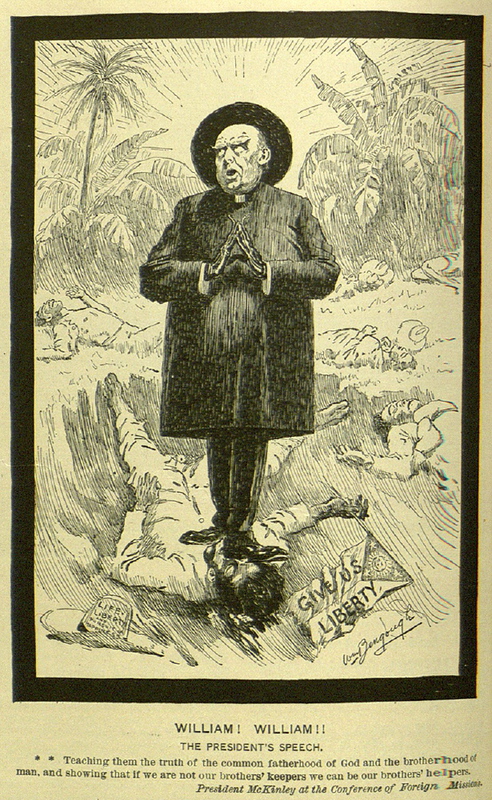

The anti-imperialist Life magazine was similarly attuned to the hypocrisy of cloaking military violence in pious rhetoric. In May 1900, for example, artist William Bengough scathingly debunked a speech by President McKinley—once again justifying the U.S. actions in taking of the Philippines by force—by depicting him as a parson standing on the face of a dead Filipino. The small print under this graphic quoted these lines from McKinley’s speech: “Teaching them the truth of the common fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man, and showing that if we are not our brothers’ keepers we can be our brothers’ helpers.”

|

“William! William!! The President’s Speech.” William Bengough, Life, May 24, 1900. Source: Widener Library, Harvard University |

U.S. President William McKinley is depicted as a preacher standing on a dead Filipino, grinding his heel into the man’s face. The caption quotes one of the president’s speeches: “Teaching them the truth of the common fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man, and showing that if we are not our brothers’ keepers we can be our brothers’ helpers. — President McKinley at the Conference of Foreign Missions.” The fallen man clasps the flag of the Philippine independence movement, inscribed with the words “Give Us Liberty.” His hat quotes the most famous phrase in the U.S. Declaration of Independence:“Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

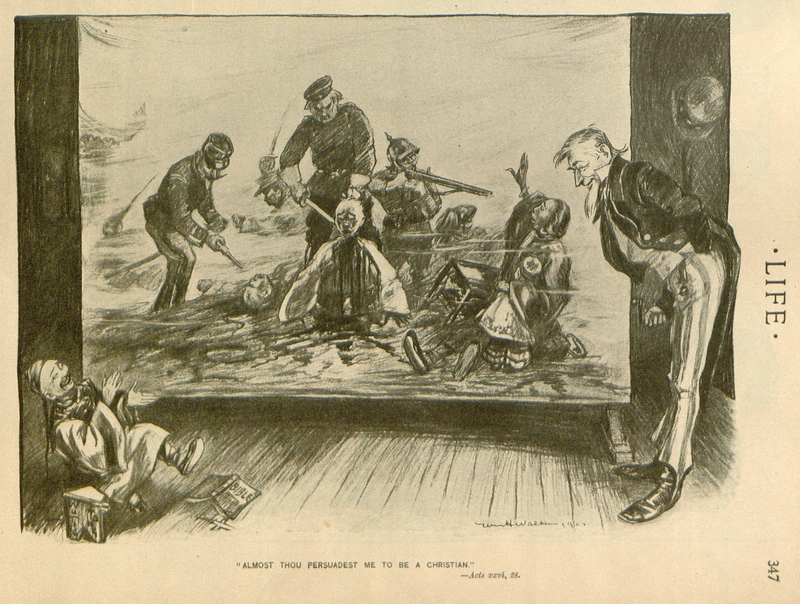

The following year, Life cartoonist William H. Walker evoked the horror of the Allied intervention in China in a graphic captioned, “Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian—Acts xxvi, 28.” A Chinese man falls off his chair, the Bible at his feet, laughing at Uncle Sam’s duplicity in preaching Christianity while showing a bloody panorama of Allied soldiers executing and marauding on a screen.

The screen in the cartoon may refer to the early films that fed public fascination with China and the Boxer crisis, including Edison’s recreation of the “Bombardment of Taku Forts by the Allied Fleets” (1900, view in the Library of Congress) and a four-minute British production that staged the murder of a missionary by Boxers called “Attack on a China Mission” (1900). The Life cartoon takes a different view of the barbarism in these events, focussing on Allied brutality against the Chinese. The caption refers to a Bible passage in which belief is nearly, but not completely reached.

|

“Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian—Acts xxvi, 28.” William H. Walker, Life, April 25, 1901. Source: Widener Library, Harvard University |

In this mocking Life cartoon, a Chinese man with an overturned Bible at his feet laughs ironically at how both the Bible and Uncle Sam relish scenes of slaughter. The 1901 date indicates that the specific reference is to Allied reprisals against Chinese civilians following the Boxer Uprising.

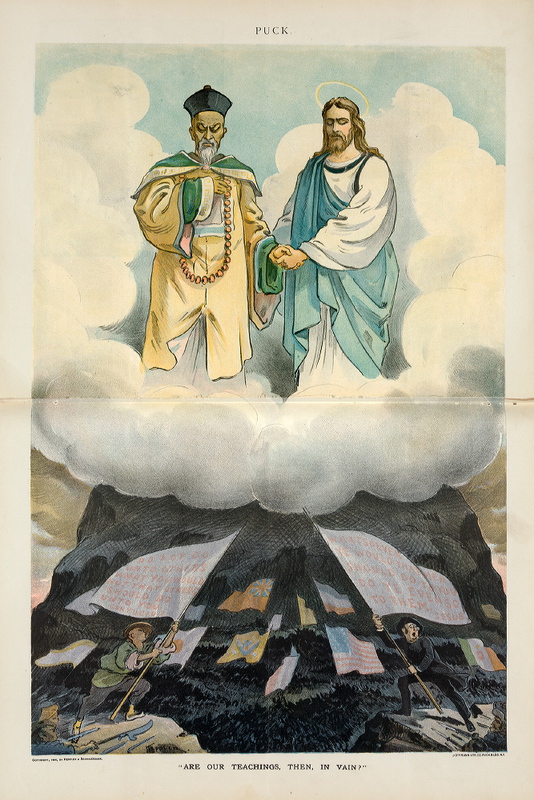

“Are our teachings, then, in vain?” is the caption of a cartoon by Puck’s Udo Keppler in which Confucius and Jesus Christ look down on the warring Boxers and missionaries. Boxers practiced spirit-possession rituals, often meeting in Buddhist temples, and attacked Christian missionaries and Chinese converts. Missionaries preaching the Gospel in rural China violated local religious practices. The enlarged detail below reveals that the flags of the opponents say the same thing in different words, each justifying their wars to uphold the principle of the “Golden Rule.”

|

“Are our teachings, then, in vain?” Udo Keppler, Puck, October 3, 1900. Source: Library of Congress

This rueful cartoon places Confucius and Jesus side-by-side and laments the failure of all parties to practice what they preach. The banners of both side pronounce fidelity to the “golden rule.”

Boxer banner (Chinese forces flags): “Do not do unto others what you would not that others should do unto you. Confucius”

Missionary banner (Allied forces flags): “Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you do ye even so to them. Jesus” |

WHO IS THE BARBARIAN?

In an 1899 cartoon, René Georges Hermann-Paul attacked the hypocrisy of spreading civilization by force by juxtaposing the words “Barbarie” and “Civilisation” beneath Chinese and French combatants who alternate as victor and victim. When the Chinese man raises his sword, it is labeled “barbarism,” but when the French soldier does precisely the same thing it is “a necessary blow for civilization.”

|

“Barbarie — Civilisation.” Full caption: “It’s all a matter of perspective. When a Chinese coolie strikes a French soldier the result is a public cry of ‘Barbarity!’ But when a French soldier strikes a coolie, it’s a necessary blow for civilization.” René Georges Hermann-Paul, Le Cri de Paris, July 10, 1899. |

What did the public back home know about the fighting of these far-off wars? Each of the three major turn-of-the-century wars left a trail of contention in the visual record. In the U.S., pro-imperialist graphics created the image of robotic, unstoppable American soldiers stomping on foreign lands and towering over barefoot savages. Anti-imperialist protesters were often feminized as weak “nervous Nellies” and, in a play on words, as “aunties.” Antiwar graphics, on the other hand, informed the public about the darker side of imperial campaigns.

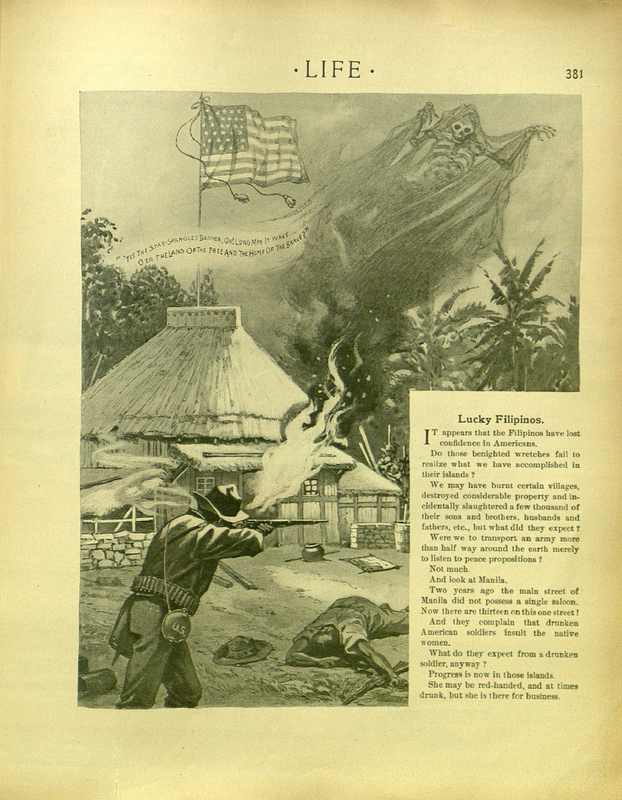

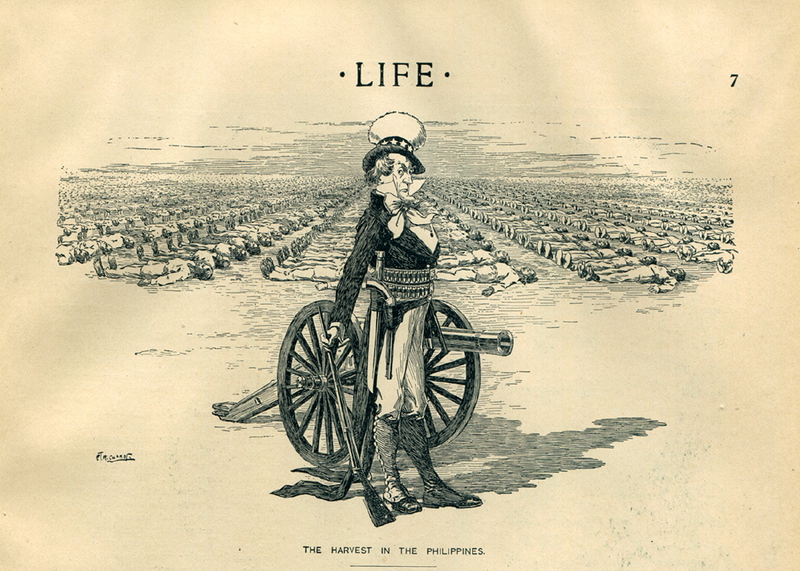

“Lucky Filipinos”: the Philippine-American War

Life published many graphics that showed the humanitarian costs inflicted by war and political aggression—despoliation, looting, concentration camps, torture, and genocide—often awkwardly interspersed amongst humorous sketches and domestic scenes. The graphics protesting U.S. actions in the Philippines were particularly biting, as seen in a page satirically titled “Lucky Filipinos.” Rising from the flames of a burning home, a skeletal apparition represents the hundreds of thousands of Filipinos killed in the U.S. campaign. Under the American flag, patriotic words end with a question mark:

‘Tis the Star-Spangled Banner, Oh! Long May It Wave.

O’er The Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave?

|

“Lucky Filipinos.” Life, May 3, 1900. Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

|

The long text accompanying this grim illustration reads as follows:

Lucky Filipinos.

It appears that the Filipinos have lost confidence in Americans.

Do those benighted wretches fail to realize what we have accomplished in their islands?

We may have burnt certain villages, destroyed considerable property and incidentally slaughtered a few thousand of their sons and brothers, husbands and fathers, etc., but what did they expect? Were we to transport an army more than half way around the earth merely to listen to peace propositions?

Not much.

And look at Manila.

Two years ago the main street of Manila did not possess a single saloon. Now there are thirteen on this one street!

And they complain that drunken American soldiers insult the native women.

What do they expect from a drunken soldier, anyway?

Progress is now in those islands.

She may be red-handed, and at times drunk, but she is there for business.

“Scorched earth” tactics destroyed scores of villages. How such uncivilized behavior fit the rhetoric of the civilizing mission is the subject of the Life cartoon, “A Red-Letter Day.” Against a backdrop of distant flames, a Filipino man—sympathetically drawn as tall, handsome, and heroic in contrast to the usual caricature of a tiny, expressionless savage in a grass skirt—is questioned by a clergyman. The caption reads: “The Stranger: How long have you been civilized? The Native: Ever since my home was burned to the ground and my wife and children shot.”

|

“A Red-Letter Day. The Stranger: How long have you been civilized? The Native: Ever since my home was burned to the ground and my wife and children shot.” Frederick Thompson Richards, Life, October 18, 1900. |

The dignity of the bereaved Filipino in this cartoon is a stark contrast to the usual demeaning stereotypes of “half devil and half child” that Kipling endorsed and many cartoonists reinforced. In this rendering it is the Bible-toting white invader (“The Stranger”) who is ridiculed.

“Le Silence”: the Second Anglo-Boer War

The French leftwing magazine L’Assiette au Beurre (The Butter Plate) had a substantive run from April, 1901 to October, 1912. Dominated by full-page graphics, many issues were thematic visual essays developed by a single artist. In the September 28, 1901 issue, artist Jean Veber excoriated the shameful subject of the concentration camps British forces used to weaken Boer resistance in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902. The strategy was among several emerging in these “small wars” of the turn of the century.

Initially, the camps were conceived as shelters for women and children war refugees. British armies had difficulty stopping mounted Boer commandos spread out over large areas of open terrain. The campaign was stepped up to target the civilian population that provided crucial support for guerrilla fighters in both the Transvaal and Orange Free State republics. Families were burned out of their homes and imprisoned in concentration camps.

Though black Africans did not fight in the war, over 100,000 were rounded up and confined in camps separate from the white internees. All of the hastily organized camps, for whites and blacks alike, had inadequate accommodations, wretched sanitation, and unreliable food supplies, leading to tens of thousands of deaths from disease and starvation. A post-conflict report calculated that close to 28,000 white Boers perished (the vast majority of them children under sixteen), while fatalities among incarcerated native Africans numbered over 14,000 at the very least.

The British people had a long history of supporting imperial wars and as the conflict escalated, criticism in cartoon form declined and was supplanted by patriotic messages. French artists, on the other hand, leveled charges of barbarism against Great Britain and other imperial powers, including their own country, in vivid graphics. Veber’s series, “Les Camps de Reconcentration au Transvaal,” begins with the cover image “Le Silence,” in which a veiled woman holds her finger to her lips, standing over the remnants of what appears to be an electric fence and a plow that suggests the earth has been tilled to bury evidence.

|

“Les Camps de Reconcentration au Transvaal. Le Silence” (Concentration Camps in the Transvaal. Silence). Jean Veber,L’Assiette au Beurre, September 28, 1901. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France |

This special issue of L’Assiette au Beurre drew particular attention to the brutal tactics adopted by the British in the Boer War, including herding the families of the Boer opponent into concentration camps. Stark images such as these helped make public a subject that was generally suppressed.

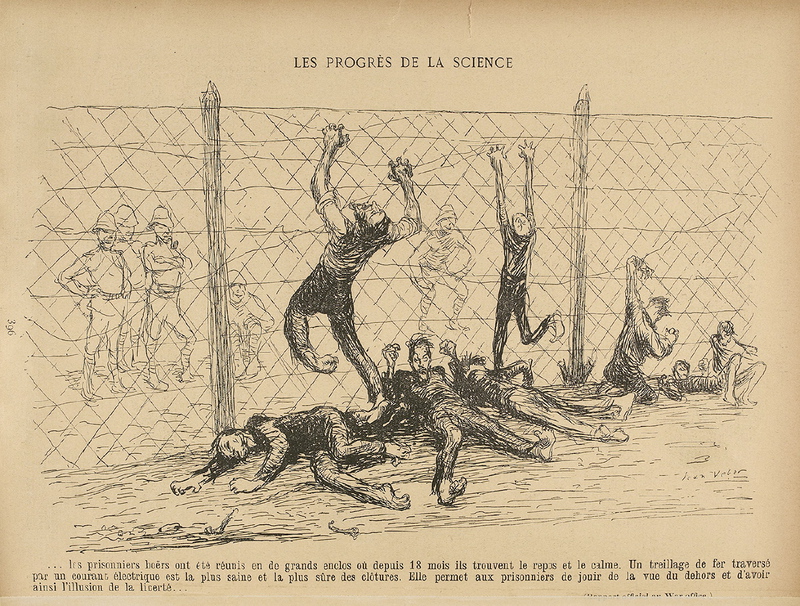

In Veber’s rendering of “Les Progrès de la Science” (The Advancement of Science), Boer prisoners of war are being shocked by an electric fence to the amusement of British troops on the other side. The image is ironically paired with a quote attributed to an “Official Report to the War Office” that says ”iron railing through which an electric current runs makes the healthiest and safest fences.”

|

“Les Progrès de la Science” (The Advances of Science). Jean Veber, L’Assiette au Beurre, September 28, 1901. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

British soldiers laugh at the spectacle of Boer prisoners of war being shocked by an electric fence. The title of the cartoon calls attention to the barbarous uses of much modern technology and so-called “progress.”

…les prisonniers boërs ont été réunis en de grands enclos où depuis 18 mois ils trouvent le repos et le calme. Un treillage de fer traversé par un courant électrique est la plus saine et la plus sûre des clôtures. Elle permet aux prisonniers de jouir de la vue du dehors et d’avoir ainsi l’illusion de la liberté… (Rapport officiel au War Office.)

… the Boer prisoners were gathered in large enclosures where, for the last 18 months, they found rest and quiet. An iron railing through which an electric current runs is the healthiest and safest of fences. It allows prisoners to enjoy the view from the outside and have the illusion of freedom … (Official Report to the War Office.) |

In an image titled, “Vers le Camp de Reconcentration” (To the Concentration Camp), women and children are dragged off by British soldiers. The caption again ironically quotes an “Official Report to the War Office” that praises the British soldiers’ bravery in the face of a fierce enemy, in this case women and children: “The humanity of our soldiers is admirable and does not tire despite the ferocity of Boers.”

|

“Vers le Camp de Reconcentration” (To the Concentration Camp). Jean Veber, L’Assiette au Beurre, September 28, 1901. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Women and children were included among the Boer prisoners of the British. The French caption mocks British hypocrisy in officially praising the humanitarian behavior of their armed forces.

hier encore nous avons pris un important commando. Je l’ai fait reléguer sous bonne escorte. L’humanité de nos soldats est admirable et ne se lasse pas malgré la férocité des Boërs … (Rapport officiel au War Office.)

… yesterday we took important commandos. I relegated an escort. The humanity of our soldiers is admirable and does not tire despite the ferocity of the Boers … (Official Report to the War Office.) |

“Is This Imperialism?”: the Boxer Uprising

In the eyes of the West, China was dangerously close to chaos as the new century began. World powers competing for spheres of influence within her borders had grown ever bolder in their demands as the Qing rulers appeared increasingly weak. Western missionaries had penetrated the interior, and the missions they established disrupted village traditions. The influx of cheap Western goods eroded generations-long trading patterns, while telegraph and railroad lines were constructed in violation of superstitions, eliciting deep resentment among Chinese. Some of the poorest provinces in the north were further stressed by a destructive combination of flooding and prolonged drought. There, membership in militant secret societies swelled, most prominently in the Yi He Quan (Society of the Righteous Fist), a sect known to Westerners as the Boxers.

Christian missionaries, their Chinese converts, and eventually all foreigners were blamed for the troubles and attacked by Boxer bands of disenfranchised young men. By the spring of 1900, Boxer attacks were spreading toward the capital city of Beijing. Foreign buildings and churches were torched and the Beijing-Tianjin railway and telegraph lines were dismantled, cutting communication with the capital. A rescue expedition made up of troops from eight nations, under the command of the British Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour, left Tianjin for Beijing. The expedition met with unexpectedly fierce opposition from Boxers and Qing dynasty troops and was forced to retreat. On June 17, while the fate of Seymour and his men remained unknown to the outside world, Allied navies attacked and captured the forts at Taku. In one of the most lasting images of the conflict, the legation quarter in Beijing—overflowing with some 900 foreign diplomats, their families, and soldiers, along with some 2,800 Chinese Christians—was put to siege. On June 21 the Empress Dowager Cixi declared war on the Allied nations.

The Boxer Uprising was a godsend for the righteous exponents of a world divided

between the civilized West and barbaric Others. As the disturbance escalated, so did news coverage around the world. Reports of the Boxer attacks seeped out of the beleaguered area and misinformation spread, like this headline in the New York Times on July 30: “Wave of Massacre Spreads over China. All Missionaries and Converts Being Exterminated. Priests Horribly Tortured. Wrapped in Kerosene-Soaked Cotton and Roasted to Death.”

In this same horrified mode, the July 28 cover of Harper’s Weekly—a publication that carried the subtitle “A Journal of Civilization”—depicted demonic Boxers brandishing primitive weapons, carrying severed heads on pikes, and trampling a child wrapped in the American flag. Uncle Sam and President McKinley countered the assault under another American flag on which was inscribed “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness under treaty rights.” The cartoon caption reflected America’s self-image as a reluctant civilizer: “Is This Imperialism? No blow has been struck except for liberty and humanity, and none will be.”

|

“Is this Imperialism? ‘No blow has been struck except for liberty and humanity, and none will be.’—William McKinley.” W. A. Rogers, Harper’s Weekly, July 28, 1900. Source: Widener Library, Harvard University |

As the caption indicates, this cover illustration dismisses charges of imperialism that critics directed against American expansion at the turn of the century.Harper’s Weekly took pride in billing itself as “A Journal of Civilization.” The barbarians depicted here are Chinese Boxers who committed atrocities against Christian missionaries.

After Allied forces were dispatched to relieve the sieges in Tianjin and Beijing, however, it did not take long before news reports and complementary visual commentary began to take note of barbaric conduct on both sides of the conflict. U.S. regiments were transported from the Philippines to join the Allied force. In an unprecedented alliance, the second expeditionary force was comprised of (from largest troop size to smallest) Japan, Russia, Great Britain, France, U.S., Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. On China’s side, the Boxers were absorbed into the Qing government forces to fight the invaders. Allied troops departed Tianjin for Beijing on August 4.

Despite several victories in the battle for Tianjin, chaotic Chinese forces melted away before the Allied advance. With little opposition, Allied troops foraged for food and water in deserted villages, where the few who remained—often servants left to protect property—usually met with violence. Accusations of atrocities against civilians on the ten-day march to Beijing were made in first-hand accounts of the mission. Although protested by some commanders, no single approach prevailed among these competitive armies thrown together in a loose coalition. Newspapers carried pictures of corpses and stories of rape and plunder, notably in the wealthy merchant city of Tongzhou just before troops reached Beijing.