CIA May be Regarded Around World as a Rogue Elephant, But Operatives Can Still Churn Out Books that Make Themselves Look Like Heroes

And the Washington foreign policy establishment still eats them up

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

In 1975, Philip Agee published his book Inside the Company: CIA Diary. In the introduction, he wrote:

“When I joined the CIA, I believed in the need for its existence. After twelve years with the agency I finally understood how much suffering it was causing, that millions of people all over the world had been killed or had their lives destroyed by the CIA and the institutions it supports. I couldn’t sit by and do nothing and so began work on this book.”

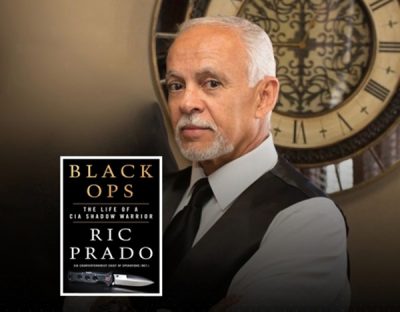

Enrique Prado’s book, Black Ops: The Life of a CIA Shadow Warrior (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2022), is written for the opposite purpose. Prado says,

“This book is my attempt to correct the misperceptions that make the Agency one of the least understood and most mistrusted institutions in America today. The reality we faced on the ground in places from Muslim Africa to East Asia, to our own streets here at home, is one of persistent threats that must be countered to keep our people safe.”

Prado’s memoir was approved for publication by the CIA. It is self-laudatory and highly critical of restraints on the CIA. It confirms that, while the ability to assassinate at will was temporarily restricted, CIA sabotage and paramilitary operations against other nations have continued non-stop.

Background

Enrique (Ric) Prado’s father lost his business in the Cuban Revolution and Ric came to the U.S. as a youth in the early 1960s. He grew up in greater Miami. The Vietnam War was raging and his “dream was to go to Vietnam.”

After high school, Ric enlisted in the U.S. Air Force and received training in rescue operations including parachute jumping and scuba diving. Prado’s dream was dashed because the Vietnam War was winding down and the U.S. military downsizing.

Prado alludes to his involvement with Cuban-American gangs and some troubled years. Then, starting with contract work, Prado began to perform assignments for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Prado and the Contras

Prado’s timing was late for Vietnam but just right for Central America. In 1979 the Sandinista Revolution overthrew the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua. As a Spanish-speaking Latino, Prado was not a typical Anglo-American. He was recruited as a CIA officer responsible for overseeing the development of the Contra army based in Honduras and conducting cross-border attacks on communities in Nicaragua.

He writes, “In these early days, there were only five CIA officers who interfaced directly with the Contras in Tegucigalpa; none were yet in the field.” There were “ten camps that lay scattered along the Honduran Nicaraguan border.” Ric Prado became the CIA officer responsible for going to the camps to coordinate support and conduct weapons training.

Prado admits the Contra leadership came from the corrupt Somoza regime: “Others who had been part of Somoza’s military…formed the core leadership of the Contras.” Initially, Washington subcontracted the job of mobilizing the Contras to Argentinian military officers who had experience from their own dirty war and death squads. Prado is extremely critical of the Argentinian military trainers, calling them a “den of snakes” and stating that, “to a man, I found them to be useless parasites.” The Argentinian military trainers were supplanted by CIA personnel, with Ric Prado playing a leading role overseeing Contra operations from Honduras and later in the “southern front” in Costa Rica.

The CIA is funded by Congress and acutely aware of its public image. Whether it is creating negative press for “enemies” such as Nicaragua, Cuba or Russia, or creating positive press for itself, manipulating the media is an important part of its work. Prado talks about the political benefits of recruiting Indigenous Miskitos to the Contras: “Miskitos were popular with several U.S. political sectors. Among Native Americans and some prominent liberals, the Miskitos were considered to be the oppressed, indigenous forces untainted by association with Somoza. That political viability back in the States with elements often hostile to the Agency helped us enormously.”

The unofficial war on Nicaragua included attacks on infrastructure which echo today with the U.S. sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipelines. Prado proudly documents the attack on the Puerto Cabezas pier and underwater gas pipeline: “The dock included an integrated fuel pipeline for faster transfer of oil from tankers. If we could destroy this…we’d make a big statement by blowing up the key link between the Sandinistas and their communist allies….We received exactly what we needed: a specialized underwater demolition charge that combined compactness with tremendous blast power….The charge exploded…the blast was so large it destroyed the fuel pipeline.”

Prado documents the failed attempt to blow up a bridge at Corinto on the Pacific coast. For unknown reasons, Prado was re-assigned and left Honduras in March 1984 after four years managing the Contras. He returned to the Contra campaign in the summer of 1986. They had safe houses and secret bases in ranches along the Nicaragua-Costa Rica border. It was more difficult because the Costa Rican government did not support the Contras as Honduras did.

Prado briefly describes the sensational events in October 1986 when a CIA plane dropping supplies and weapons to Contras was shot down. The pilot and two others on the flight died, but ex-Marine Eugene Hasenfus survived and was captured. Unmentioned in the book, this was a sensational news event at the time. Beyond the drama of an American plane being shot down over Nicaragua and an American captured and taken prisoner, it revealed the CIA was violating the congressional Boland Amendment prohibiting U.S. military support for overthrowing the Nicaragua government.

The Reagan administration denied responsibility. Elliott Abrams, the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, said:“The flight in which Mr. Hasenfus took part was a private initiative…It was not organized, directed or financed by the U.S. Government.” The counter-evidence was overwhelming and the CIA was caught red-handed violating the congressional resolution and then lying about it. This is unmentioned in the book. Instead, Prado criticizes Hasenfus for having personal identification papers in his possession.

Prado’s Pride

In 1990, after ten years of terrorist attacks by the Contras, combined with economic and political attacks from Washington, Nicaraguans cried “Uncle” and voted the Sandinistas out of power.

Prado says, “our Contra program was a definitively successful black op carried out solely by key personnel from the CIA.” Prado stated further that “that Cuban kid who lost his native country to revolutionaries now helped cut off some of the communist tentacles that threatened to engulf Latin America.”

Prado believes the use of a proxy army to fight against a perceived enemy was an important victory and re-established the credibility of the CIA. He says, “The Contras resuscitated the post-Vietnam decimated CIA back to relevance.”

Prado is annoyed at negative media portrayals of the CIA Contra program. The movie American Made, depicting the story of an American pilot taking guns to the Contras and bringing cocaine back into the U.S., is especially annoying to Prado. He ignores the fact that tens of thousands of Nicaraguans died and cocaine inundated some U.S. cities as a byproduct of the Contra program.

Source: streetsoflima.com

Prado believes that the CIA were the “good guys” in Nicaragua. The International Court of Justice thought otherwise.

In 1986 the court ruled that the U.S. attacks on Nicaragua were violations of international law. The Reagan administration and media largely ignored the ruling.

Later, journalist Gary Webb documented the catastrophic social damage inside the U.S. caused by the cheap cocaine flooding some U.S. cities. Webb was attacked by establishment media. However, in 1998, the CIA Inspector General acknowledged, “There are instances where C.I.A. did not, in an expeditious or consistent fashion, cut off relationships with individuals supporting the contra program who were alleged to have engaged in drug-trafficking activity, or take action to resolve the allegations.”

The 2014 movie Kill the Messenger, based on the true and tragic story of Gary Webb, was undoubtedly another movie that irritated Ric Prado.

Justifying Terrorism and Sabotage

Prado’s justification for CIA crimes against other countries is U.S. national security. He says, “The spread of communism through Central and South America became a direct threat to the security of the United States.” He compares the war against “communism” to the World War II fight against Nazi Germany. He says, “The Sandinistas quickly consolidated their power through Nazi-like pogrom and oppression.”Prado says that training the Contras was like “being an OSS officer trying to train and supply the French resistance to the Germans in WW2.”

The U.S. deployed Nicaraguans, Afghans and extremist Arab recruits in proxy wars across the globe. Prado assesses this a great success: The Mujahedin in Afghanistan and Contras in Nicaragua “played crucial roles in the Cold War’s final act.”

Prado does not mention the fact that the Sandinistas were voted back into power in Nicaragua in 2006 after 16 years of neo-liberal rule. The country was in very poor shape with privatized education, little health care, and terrible infrastructure. Since being voted back, the Sandinistas have won increasing levels of support because they have substantially improved the lives of most Nicaraguans. As in the 1980s, Nicaragua is back on the U.S. enemy list and Western media portrayals are universally negative.

Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas enjoy great popularity today despite the CIA efforts to destroy the revolution that they led in the 1980s. [Source: resumenlatinamericano.org]

Prado in Other Countries

The “CIA shadow warrior” went on to conduct operations in Peru, the Philippines, South Korea and an unnamed African country, probably the Central African Republic. “We were the leadership cadre, spearheading America’s effort against global terrorism.”

Prado says, “Radical Islamic terrorism at the turn of the century morphed into a deadly new enemy.” With the attacks of 9/11, the U.S. homeland was suddenly the victim of a real attack. The timing was very convenient for war hawks and those who wanted a “new American Century.” From being a president who took office under highly contested circumstances, Bush became a “war President.” The 9/11 attack provided a Pearl Harbor moment justifying U.S. military aggression in the Middle East.

Prado describes the fervor and intensity with which the CIA responded: CIA agents worked long hours to identify, capture and sometimes kill those deemed to be “enemy combatants.” Some of these suspects were tortured in violation of the UN Convention Against Torture, to which the U.S. is a signatory. The “CIA shadow warrior” is dismissive of the critics. The “much maligned enhanced interrogations [were] sparingly performed on known terrorists.”

“Jungle of Criminality”

Prado views the world as “a jungle of criminality, corruption, betrayals, and atrocious human rights abuses we were determined to help eradicate.” There are numerous allusions to the “good guys” fighting the “bad guys.”

Prado does not attempt to argue with critics who say some CIA actions are violations of international law and human rights. It is estimated that 30,000 Nicaraguans died in the Contra War. This is ten times more than died in the attacks of 9/11 in a country that only had 3.3 million people at the time.

Prado’s claim that Sandinista Nicaragua posed a threat to U.S. “national security” stretches credulity. The CIA actions not only violated international law; they violated U.S. law.

Prado never questions why some people around the world hate the U.S. government. For him, they are simply the “bad guys.” This is much more convenient than looking at the real causes. Chalmers Johnson, in the introduction to his book Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire (Holt Books, 2001), put it succinctly: “The attacks of September 11 descend in a direct line from events in 1979, the year in which the CIA, with full presidential authority, began carrying out its largest ever clandestine operation—the secret arming of Afghan freedom fighters (mujaheddin) to wage a proxy war against the Soviet Union, which involved the recruitment and training of militants from all over the Islamic world.”

The results in Afghanistan were even more disastrous than in Nicaragua. They toppled a popular government, creating decades of chaos and extremism. With the Soviets gone, the U.S. dumped Afghanistan and moved on to attack Iraq and place troops in Saudi Arabia. As Johnson says, “The suicidal assassins of September 11, 2001, did not ‘attack America,’ as political leaders and news media in the United States have tried to maintain; they attacked American foreign policy.”

Intelligence Serving the War Machine

In the 1960s and 1970s, CIA officers Phil Agee and John Stockwell, author of In Search of Enemies, came to realize that U.S. foreign policy is not in the national interest. Performing coups, destabilizing foreign governments and promoting death squads (as is documented in the 2020 book, The Jakarta Method: Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade & The Mass Murder Program That Shaped Our World) is not only against international law and the UN Charter, it is against what the U.S. claims to be for. They spoke out courageously. Ric Prado is far from this realization.

No doubt there are many hard-working and dedicated analysts and officers at the CIA. No doubt they come up with real intelligence. But given the biases and delusions, they can also be wildly inaccurate. Prado writes,

“Threats America faced that summer came from many quarters, but two in particular were seen as significant threats. Hezbollah was considered among the most dangerous. They had carried out operations all over the world that had killed thousands of people…Danger lurks from seemingly innocuous sources. You’ll find Hezbollah sleeper cells in your own town…Terrorists lurking and lying in wait.”

Prado says that, when 9/11 happened, one CIA officer was certain that Hezbollah was behind it. This suggests they have poor analysis because Hezbollah is very different from al-Qaeda. Hezbollah is a Lebanese resistance movement, much demonized by Israel because they successfully expelled the Israelis from southern Lebanon. They are a substantial part of the Lebanese government and oppose extremist al-Qaeda ideology and actions.

Prado’s comments about President John F. Kennedy also indicate a poor analysis. He explains away the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 to “betrayal and broken promises of the Kennedy Administration.” Looking back, it seems clear the invasion was doomed to failure. Vitriol against Kennedy may be widespread in the CIA. In recent years, important new evidence on the assassination has been revealed in several books, including JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters and The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government, among others.

As a sign of the times, Ric Prado transitioned from the CIA to a private security company, Blackwater. The “revolution in military affairs” proposed by neo-cons in the 1990s has been realized as U.S. intelligence and “black ops” are increasingly performed by private contractors. There are clear advantages: They do not have the same constraints and accountability. Prado documents how he has recruited other CIA leaders for the infamous private company.

The CIA and U.S. Foreign Policy

Ric Prado is very proud of his work at the CIA and pours compliments on many of his CIA leaders and fellow officers. He is critical of constraints on the CIA.

“Our nation’s leadership often failed to measure up. When you have pit bulls ready and willing to go after America’s enemies, only to be chained in the yard by career-obsessed managers, you cannot win a war. It only gets prolonged.”

Prado admits: “Our job was to break the laws of other nations without getting caught to defend ours. It is dark and murky work.”

In a postscript Prado says “confronting China” is now one of the Agency’s primary tasks. He recommends,

“the CIA needs to be led by vigorous, aggressive, and fearless leaders willing to take the fight to the enemy on their turf, wherever that turf may be.”

Taking “the fight to the enemy” is clearly a recipe for new conflicts. Ric Prado has learned nothing from past failures and blowback. Judging by the positive reviews of his book, neither has the Washington foreign policy establishment.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Rick Sterling is an investigative journalist based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is active with the Taskforce on the Americas and other organizations including Syrian Solidarity Movement and the Mount Diablo Peace and Justice Center. He can be contacted at [email protected]. He is a regular contributor to Global Research

Featured image: CIA officer Ric Prado with his new book lionizing the Agency. [Source: spymuseum.org]