Art and Politics, and Why Happiness Is Overrated

As the thinking man was overtaken by a great storm, he was sitting in a big car and took up a lot of space.

The first thing he did was to get out of his car.

The second was to take off his jacket. The third was to lie down on the ground.

Thus reduced to his smallest magnitude he withstood the storm.

Such was the lesson Bertoldt Brecht took from ancient Chinese theatre. 1 It was how he survived. The Nazis forced him from Germany into impoverished exile in Scandinavia. Later, he suffered humiliating anti-communist harassment in the U.S. His strategy was always: the best resistance is no resistance.

It doesn’t mean to cave. Brecht opposed his “thinking man” to an image common in European theatre: the individual “standing tall” against the wind, fighting the storm. Brecht’s realism was to see a situation for what it is, discover its real opportunities, and survive knowingly, until the storm passed.

It is not easy to do. It means seeing things as they are, not as you want them to be, suspending expectations, or at least not being defined by them. Some think it is not possible to be realist in Brecht’s sense. They say we can’t live without “dreams”, without things to “look forward to”.

They call that “hope”. The medical establishment is obsessed with it. As a cancer patient for many years, I got tired of hope. It seemed delusional. It was as if seeing things as they are – bad! – was not allowed. Realism means we can discover truth, even unexpected.

And we can learn to live with it, fully, with open eyes.

In the rich North, culturally, we don’t believe in truths. We believe in happiness and choice. Truth and happiness don’t always go together. There’s a simple reason. We are happy when expectations are realized, when dreams come to pass, when we get what we want. But expectations, dreams and desires come from society. Truth, if we believed in it, removes their lustre.

One truth, for instance, is that a fraction of the world’s population “lives well”. Another is that we live well because others don’t. We kill and rob them to be “happy”. A further truth is that we think we live well precisely because we don’t think about these truths. The people we kill and rob, after all, don’t count. Finally, it happens to be true that we don’t live well. We are mostly depressed and anxious.

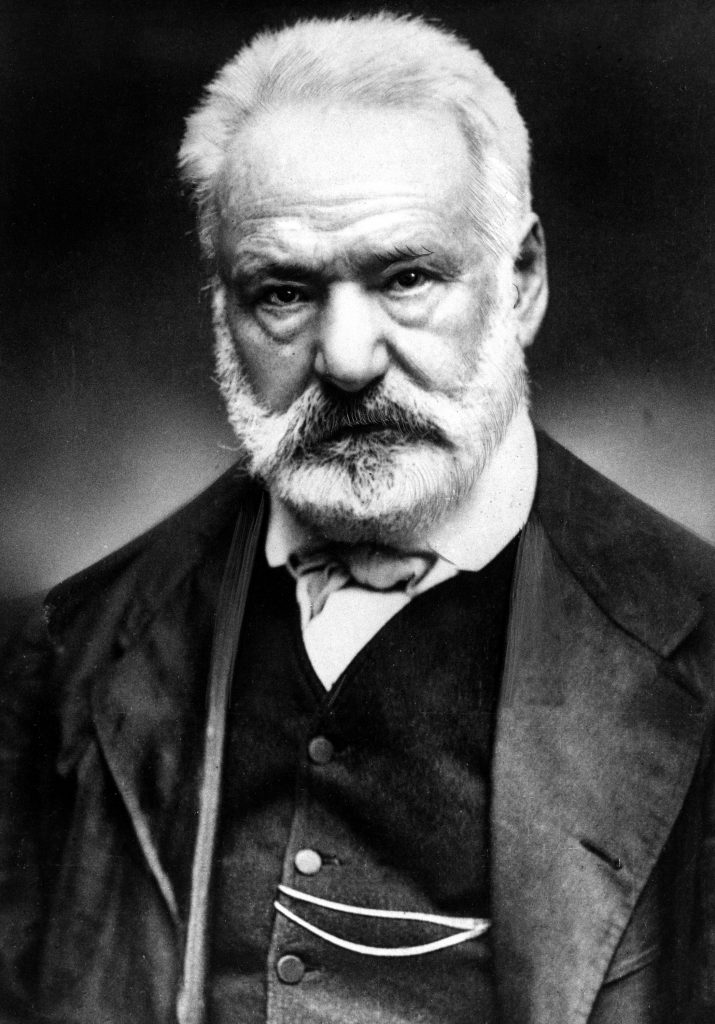

French poet, novelist and dramatist Victor Marie Hugo is shown in this undated photo. Hugo was born on May 22, 1802 in Besancon, France, and died in 1885 in Paris. (AP Photo)

Truth is an “implacable foe” of happiness. This is how Victor Hugo saw it. He wrote:

“Thoughtful people rarely use the terms, the happy and the unhappy…. The true division of humanity is this. Those filled with light and those filled with darkness”.

Hugo was a realist, like Brecht, Marx, José Martí.

It is why he valued art. He thought art, including the beauty of nature and people, matters for politics. 2 He didn’t look to art for fun, tranquility or escape. He looked for realism. Art is best experienced for what it is, not for its purpose. It might have a purpose but its value is not mainly instrumental.

Hugo thought human actions can be art. He called it “social beauty”. 3

Consider Inspector Javert. He relentlessly pursues ex-convict Jean Valjean. When Valjean has a chance to kill Javert, he frees him. Javert wants Valjean to kill him because that is what every part of him expected: an act of revenge. And when it doesn’t happen Javert feels “cut off from his past life”. Hugo writes that Javert saw what was “terrible .… He was moved”: by an instance of social beauty.

Hugo was not a liberal, as sometimes claimed. True, he valued individual freedom. But it was not the sort that liberalism proclaims: the individual “standing tall”, seizing their destiny.

We can’t do that, not as individuals.

It’s a lie, and leads to lies, like the medical establishment’s insistence on “hope”: Just believe everything will go back to where it was. It doesn’t happen, and believing it does not empower.

Hugo writes,

“There are those who ask for nothing more, living beings who, having bright blue skies above, say: This is enough … people who, as long as there are clouds of purples and gold above their heads … are determined to be happy until the stars stop shining and the birds stop singling. These are the darkly radiant. They have no idea they are to be pitied. … Whoever does not weep does not see”.

The “darkly radiant”! Brecht saw an existential need for “every kind of truth”. He writes,

“When the thinking man conquered the storm, he did so because he recognized the storm and agreed to it. Thus, if you want to conquer death, you should recognize it and agree to it”.

It is a more interesting view of freedom than the one we’ve been saddled with for centuries of liberalism. It would be good if philosophers and political theorists looked further afield: Martí, Marx, even the Buddha. (He thought the “standing tall” image was evil).

Truth is only ever approximate. But we can keep moving in the direction.

Raúl Roa, student leader in the 1930s uprising in Cuba, later Cuba’s foreign minister, once defined humanism as the identification of lies. Humanism, he wrote, is “awareness in the face of conceptions that undermine, deform and eliminate the human personality”.4

Roa had in mind the lies of imperialism, including liberalism’s naïve freedoms: See the lies, and you’ll start to see beauty: social beauty.

Ana Belén Montes is social beauty, locked up under undeservedly harsh and demeaning conditions. 5

Susan Babbitt is author of Humanism and Embodiment (Bloomsbury 2014) and José Martí, Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Global Development Ethics (Palgrave MacMillan 2014).

Notes

1. Stephen Parker, Bertoldt Brecht: A literary life (2014)

2. Carmen Suárez León, José Martí y Victor Hugo, en el fiel de las modernidades (Havana: Centro de investigación y desarrollo de la cultura cubana, 1996)

3. I am grateful to Dr. Robert Rennebohm for pointing this out.

4. Bufa subversiva Havana: Ediciones la memoria, 2006

5. http://www.prolibertad.org/ana-belen-montes. For more information, write to the [email protected] or [email protected]

Featured image is from Wikimedia Commons.