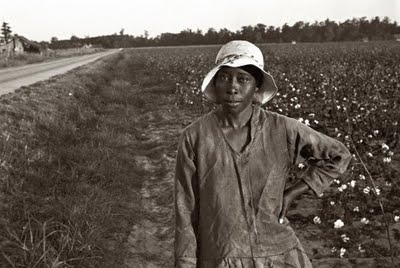

150 Years of US Civil Rights Legislation and the Struggle for Black Power

African Americans continue to fight for human dignity and self-determination

After the passage of the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865, which supposedly eliminated involuntary servitude, a series of Civil Rights Acts were passed by the Congress beginning in 1866.

Prior to the 13th Amendment, President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation which had ostensibly eliminated chattel slavery in the antebellum South beginning on January 1, 1863. However, the Civil War over the secession of the slave-holding states from the Union was far from resolution. It would take another two years for the collapse of the Confederacy to take place.

In the concluding months of the Civil War the question of how the nearly four million enslaved Africans and some five hundred thousand others designated as “free” were to be treated when the states rejoined the country under the leadership of Washington. This was a major cause of concern to ruling interests. Even Lincoln himself was not convinced that Africans should be given full citizenship rights and could perhaps be deported to Africa or Haiti.

As a result of the heroic role Africans played in the breakup of the plantation system and the defeat of the Confederate military, the demand for land and reparations emerged from the advanced ranks of the African resistance forces who were by no means willing to accept a form of neo-slavery after the surrender of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee. Therefore, prior to the issuance of General William T. Sherman’s Field Order No. 15 of January 1865 and other subsequent military, administrative and legislative actions, Africans were seeking to liberate themselves from human bondage and national oppression.

W.E.B. Du Bois in his seminal work entitled “Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880, published during the Great Depression in 1935, reflects on the liberation process initiated by the African people in a chapter entitled “The General Strike” saying: “This was not merely the desire to stop work. It was a strike on a wide basis against the conditions of work. It was a general strike that involved directly in the end perhaps a half million people. They wanted to stop the economy of the plantation system, and to do that [Africans] left the plantations. At first, the commanders were disposed to drive them away, or to give them quasi-freedom and let them do as they pleased with the nothing that they possessed. This did not work. Then the commanders organized relief and afterward, work.” (p. 67)

The chapter continues noting, “The Negroes were willing to work and did work, but they wanted land to work, and they wanted to see and own the results of their toil. It was here and in the West and the South that a new vista opened. Here was a chance to establish an agrarian democracy in the South with peasant holders of small properties, eager to work and raise crops, amenable to suggestion and general direction. All they needed was honesty in treatment, and education. Wherever these conditions were fulfilled, the result was little less than phenomenal. This was testified to by Pierce in the Carolinas, by Butler’s agents in North Carolina, by the experiment of the Sea Islands, by Grant’s department of Negro affairs under Eaton, and by Banks’ direction of Negro labor in Louisiana. It is astonishing how this army of striking labor furnished in time 200,000 Federal soldiers whose evident ability to fight decided the war.”

Sherman met with several African leaders many of whom were minister of churches in Savannah, Georgia to facilitate the transfer of 400,000 acres of land to the formerly enslaved. These developments took place after what was called the “March to the Sea” from Atlanta to Savannah which eventually created the conditions that cleared out the Confederate troops across the coastline of Florida, Georgia and South Carolina including the South Sea Islands.

Radical Republicans in the Congress had already been discussing land redistribution plans aimed at disempowering the planters and creating a political base for their party in the aftermath of the War. Nonetheless, after the assassination of Lincoln and the ascendancy of Vice-President Andrew Johnson to the head-of-state, the Order was nullified and the confiscated land was returned to the former slave owners.

From Reconstruction to Peonage

During the years of 1866-1875, the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution were passed along with other Civil Rights legislation. Nonetheless these laws were not enforced with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorist organizations which re-instituted conditions that were quite similar to slavery, known as peonage.

Starting with the Federal Hayes-Tillman Compromise of 1876 and continuing through the close of the 19th century, reactionary legislation within the southern state governmental structures largely excluded African Americans from voting and holding public office keeping all political power within the control of the white ruling class. The lynching of African Americans became a routine mechanism of social control aimed at the super-exploitation of Black labor.

Despite the widespread institutionalized repression of the African American masses, resistance movements sprang up through the latter decades of the 19th century through the early 1950s. The Women’s Club Movement; a vibrant independent press; the Niagara Movement, the NAACP co-founded by Du Bois, the UNIA formed by Marcus Garvey, along with the thousands of African Americans who joined the Communist Party and other left organizations between World War I and World War II, represented a continuation of the rebellions initiated during slavery and the Civil War.

Although these efforts mobilized and organized millions of African Americans and their allies there was limited progress over the course of the period after the failure of Reconstruction until the ending of the second world war. After 1945 with the rise of national liberation struggles and socialist revolutions internationally, the movement against racism in the U.S. gained impetus sparking the unprecedented decades of gains after a century of strife.

The Modern Civil Rights Era and the Struggle for Socialism

Starting in 1957 another cluster of Civil Rights legislation was approved by Congress including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. The failure of the Civil Rights Act of 1966 focusing on fair housing suffered defeat amid the rise of the Black Power Movement and urban rebellions.

The Fair Housing Act was not passed until 1968 in the aftermath of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Since the late 1970s through the present period, a series of federal court decisions and failure to enforce existing anti-racist laws, have led to tremendous setbacks for African Americans.

This election year of 2016 is marked by a total absence of discussions and debates by the Democratic and Republican presidential candidates over the status of African Americans and oppressed peoples inside the U.S. Should there be a new push for renewed legislation as opposed to a greater emphasis on mass civil disobedience, boycotts, urban rebellions and general strikes or combination of all of these tactics aimed at total equality and full national liberation? What is obvious is that the present system of declining capitalism and imperialist militarism offers no future for the African American people and the working class in general.

Only the realization of socialism where the people control the means of production will there be any possibility of eliminating racism, national oppression and economic exploitation. There can only be freedom for the oppressed with the expropriation of the ruling class and the radical redistribution of wealth to the working people.