The US Hand in the Syrian Mess

Neocons and the mainstream U.S. media place all the blame for the Syrian civil war on President Bashar al-Assad and Iran, but there is another side of the story in which Syria’s olive branches to the U.S. and Israel were spurned and a reckless drive for “regime change” followed, writes Jonathan Marshall.

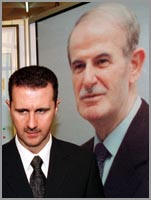

Syria’s current leader, Bashar al-Assad replaced his autocratic father as president and head of the ruling Ba’ath Party in 2000. Only 35 years old and British educated, he aroused widespread hopes at home and abroad of introducing reforms and liberalizing the regime. In his first year he freed hundreds of political prisoners and shut down a notorious prison, though his security forces resumed cracking down on dissenters a year later.

But almost from the start, Assad was marked by the George W. Bush administration for “regime change.” Then, in the early years of Barack Obama’s presidency, there were some attempts at diplomatic engagement, but shortly after a civil conflict broke out in 2011, the legacy of official U.S. hostility toward Syria set in motion Washington’s disastrous confrontation with Assad which continues to this day.

Thus, the history of the Bush administration’s approach toward Syria is important to understand. Shortly after 9/11, former NATO Commander Wesley Clark learned from a Pentagon source that Syria was on the same hit list as Iraq. As Clark recalled, the Bush administration “wanted us to destabilize the Middle East, turn it upside down, make it under our control.”

Sure enough, in a May 2002 speech titled “Beyond the Axis of Evil,” Under Secretary of State John Bolton named Syria as one of a handful of “rogue states” along with Iraq that “can expect to become our targets.” Assad’s conciliatory and cooperative gestures were brushed aside.

The Assad regime received no credit from President Bush or Vice President Dick Cheney for becoming what scholar Kilic Bugra Kanat has called “one of the CIA’s most effective intelligence allies in the fight against terrorism.” Not only did the regime provide life-saving intelligence on planned al-Qaeda attacks, it did the CIA’s dirty work of interrogating terrorism suspects “rendered” by the United States from Afghanistan and other theaters.

Syria’s opposition to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and its suspected involvement in the February 2005 assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri deepened the administration’s hostility toward Damascus.

Covertly, Washington began collaborating with Saudi Arabia to back Islamist opposition groups including the Muslim Brotherhood, according to journalist Seymour Hersh. One key beneficiary was said to be Abdul Halim Khaddam, a former Syrian vice president who defected to the West in 2005. In March 2006, Khaddam joined with the chief of Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood to create the National Salvation Front, with the goal of ousting Assad.

Thanks to Wikileaks, we know that key Lebanese politicians, acting in concert with Saudi leaders, urged Washington to support Khaddam as a tactic to accomplish “complete regime change in Syria” and to address “the bigger problem” of Iran.

Meanwhile, the Assad regime was striving mightily to reduce its international isolation by reaching a peace settlement with Israel. It began secret talks with Israel in 2004 in Turkey and by the following year “had reached a very advanced form and covered territorial, water, border and political questions,” according to historian Gabriel Kolko.

A host of senior Israelis, including former heads of the IDF, Shin Beit, and Foreign Ministry, backed the talks. But the Bush administration nixed them, as Egyptian President Hosni Mubarek confirmed in January 2007.

As Kolko noted, the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz then “published a series of extremely detailed accounts, including the draft accord, confirming that Syria ‘offered a far reaching and equitable peace treaty that would provide for Israel’s security and is comprehensive’ — and divorce Syria from Iran and even create a crucial distance between it and Hezbollah and Hamas.

The Bush Administration’s role in scuttling any peace accord was decisive. C. David Welch, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, sat in at the final meeting [and] two former senior CIA officials were present in all of these meetings and sent regular reports to Vice President Dick Cheney’s office. The press has been full of details on how the American role was decisive, because it has war, not peace, at the top of its agenda.

Isolating Assad

In March 2007, McClatchy broke a story that the Bush administration had “launched a campaign to isolate and embarrass Syrian President Bashar Assad. . . . The campaign, which some officials fear is aimed at destabilizing Syria, has been in the works for months. It involves escalating attacks on Syria’s human rights record. . . . The campaign appears to fly in the face of the recommendations last December of the bipartisan Iraq Study Group, which urged President Bush to engage diplomatically with Syria to stabilize Iraq and address the Arab-Israeli conflict. . . . The officials say the campaign bears the imprint of Elliott Abrams, a conservative White House aide in charge of pushing Bush’s global democracy agenda.”

Not surprisingly, Vice President Cheney was also an implacable opponent of engagement with Syria.

Attempting once again to break the impasse, Syria’s ambassador to the United States called for talks to achieve a full peace agreement with Israel in late July 2008. “We desire to recognize each other and end the state of war,” Imad Mustafa said in remarks broadcast on Israeli army radio. “Here is then a grand thing on offer. Let us sit together, let us make peace, let us end once and for all the state of war.”

Three days later, Israel responded by sending a team of commandos into Syria to assassinate a Syrian general as he held a dinner party at his home on the coast. A top-secret summary by the National Security Agency called it the “first known instance of Israel targeting a legitimate government official.”

Just two months later, U.S. military forces launched a raid into Syria, ostensibly to kill an al-Qaeda operative, which resulted in the death of eight unarmed civilians. The Beirut Daily Starwrote, “The suspected involvement of some of the most vociferous anti-Syria hawks at the highest levels of the Bush administration, including Vice President Dick Cheney, have combined with US silence on the matter to fuel a guessing game as to just exactly who ordered or approved Sunday’s cross-border raid.”

The New York Times condemned the attack as a violation of international law and said the timing “could not have been worse,” noting that it “coincided with Syria’s establishing, for the first time, full diplomatic relations with Lebanon. This was a sign that Syria’s ruler, Bashar Assad, is serious about ending his pariah status in the West. It was also a signal to Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan that Assad, whose alliance with Iran they abhor, is now eager to return to the Arab fold.”

The editorial added, “if President Bush and Vice President Cheney did authorize an action that risks sabotaging Israeli-Syrian peace talks, reversing the trend of Syrian cooperation in Iraq and Lebanon, and playing into the hands of Iran, then Bush and Cheney have learned nothing from their previous mistakes and misdeeds.”

In an interview with Foreign Policy magazine, Syrian ambassador Imad Moustapha noted that his government had just begun friendly talks with top State Department officials, including Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. “And suddenly, this [raid in eastern Syria] happens,” the ambassador said. “I don’t believe the guys from the State Department were actually deceiving us. I believe they genuinely wanted to engage diplomatically and politically with Syria. We believe that other powers within the administration were upset with these meetings and they did this exactly to undermine the whole new atmosphere.”

Despite these many provocations, Syria continued to negotiate with Israel through Turkish intermediaries. By late 2008, according to journalist Seymour Hersh, “Many complicated technical matters had been resolved, and there were agreements in principle on the normalization of diplomatic relations. The consensus, as an ambassador now serving in Tel Aviv put it, was that the two sides had been ‘a lot closer than you might think.’” Then, in late December, Israel launched Operation Cast Lead, a devastating assault on Gaza that left about 1,400 Palestinians dead, along with nine Israeli soldiers and three civilians.

Israeli Sabotage

The brief war ended in January, just before President Obama’s inauguration. Assad told Hersh that despite his outrage at Israel “doing everything possible to undermine the prospects for peace … we still believe that we need to conclude a serious dialogue to lead us to peace.” The ruler of Qatar confirmed, “Syria is eager to engage with the West, an eagerness that was never perceived by the Bush White House. Anything is possible, as long as peace is being pursued.”

Of Obama, Assad said “We are happy that he has said that diplomacy — and not war — is the means of conducting international policy.” Assad added, “We do not say that we are a democratic country. We do not say that we are perfect, but we are moving forward.” And he offered to be an ally of the United States against the growing threat of al-Qaeda and Islamist extremism, which had become major forces in Iraq but had not yet taken hold in Syria.

Assad’s hopes died stillborn. The new government of Israel under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which took office in March 2009, steadfastly opposed any land-for-peace deal with Syria. And the Obama administration lacked the clout or the will to take Israel on.

President Obama did follow through on promises to engage with Syria after a long period of frozen relations. He sent representatives from the State Department and National Security Council to Damascus in early 2009; dispatched envoy George Mitchell three times to discuss a Middle East peace settlement; nominated the first ambassador to Damascus since 2005; and invited Syria’s deputy foreign minister to Washington for consultations.

However, Obama also continued covert funding to Syrian opposition groups, which a senior U.S. diplomat warned would be viewed by Syrian authorities as “tantamount to supporting regime change.”

At home, Obama’s new policy of engagement was decried by neoconservatives. Elliott Abrams, the Iran-Contra convict who was pardoned by President George H.W. Bush and who directed Middle East policy at the National Security Council under President George W. Bush, branded Obama’s efforts “appeasement” and said Syrian policy would change only “if and when the regime in Iran, Assad’s mainstay, falls.”

Syria, meanwhile, rebuffed Washington’s demands to drop its support for Iran and for Hezbollah and reacted with frustration at the administration’s refusal to lift economic sanctions. Said Assad, “What has happened so far is a new approach. Dialogue has replaced commands, which is good. But things stopped there.”

As late as March 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton continued to defend talks with Assad,saying: “There’s a different leader in Syria now. Many of the members of Congress of both parties who have gone to Syria in recent months have said they believe he’s a reformer.”

But that stance would change a month later, when the White House condemned “in the strongest possible terms” the Damascus regime’s “completely deplorable” crackdown on political opponents in the city of Dara’a, ignoring the killing of police in the city.

That August, following critical reports from the United Nations and human rights organizations about the regime’s responsibility for killing and abusing civilians, President Obama joined European leaders in demanding that Assad “face the reality of the complete rejection of his regime by the Syrian people” and “step aside.” (In fact, a majority of Syrians polled in December 2011 opposed Assad’s resignation.)

Washington imposed new economic sanctions, prompting Syria’s U.N. ambassador, Bashar al-Jaafari, to assert that the United States “is launching a humanitarian and diplomatic war against us.” Obama’s policy, initially applauded by interventionists until he failed to send troops or major aid to rebel groups, opened the door to support from the Gulf States and Turkey for Islamist forces.

The Rise of the Salafists

As early as the summer of 2012, a classified Defense Intelligence Agency report concluded, “The salafist [sic], the Muslim Brotherhood, and AQI [al-Qaeda in Iraq, later the Islamic State]” had become “the major forces driving the insurgency in Syria.”

As Vice President Joseph Biden later admitted, “The fact of the matter is . . . there was no moderate middle. . . . [O]ur allies in the region were our largest problem in Syria. . . . They poured hundreds of millions of dollars and . . . thousands of tons of weapons into anyone who would fight against Assad except that the people who were being supplied were Al Nusra and al-Qaeda and the extremist elements of jihadis.”

As with Iraq and Libya — do we never learn? — “regime change” in Syria may well bring about either fanatical Islamist state or a failed state and no end to the violence.

Recalling Israel’s folly in cultivating Islamist rivals to Fatah (notably Hamas), Jacky Hugi, an Arab affairs analyst for Israeli army radio, recently made the remarkable suggestion that “What Israel should learn from these events is that it must strive for the survival and bolstering of the current regime at any price.” He argued:

The survival of the Damascus regime guarantees stability on Israel’s northern border, and it’s a keystone to its national security. The Syrian regime is secular, tacitly recognizes Israel’s right to exist and does not crave death. It does not have messianic religious beliefs and does not aim to establish an Islamic caliphate in the area it controls.

“Since Syria is a sovereign nation, there is an array of means of putting pressure on it in case of conflict or crisis. It’s possible to transmit diplomatc messages, to work against it in international arenas or to damage its regional interests. If there’s a need for military action against it, there’s no need to desperately look for it amid a civilian population and risk killing innocent civilians.

Israel has experienced years of a stable border with the Syrian regime. Until the war broke out there, not a single shot was fired from Syria. While Assad shifted aggression toward Israel to the Lebanese border by means of Hezbollah, even this movement and its military arm is preferable to Israel over al-Qaeda and its like. It’s familiar and its leaders are familiar. Israel has ‘talked’ through mediators with Hezbollah ever since the movement controlled southern Lebanon. It’s mostly indirect dialogue, meant to serve practical interests of the kind forced on those who have to live side by side, but pragmatism guides it.

While Hezbollah fighters are indeed bitter enemies, you will not find among them the joy in evil and cannibalism, as seen in the last decade among Sunni jihadist organizations.

Washington need not go so far as to back Assad in the name of pragmatism. But it should clearly renounce “regime change” as a policy, support an arms embargo, and begin acting in concert with Russia, Iran, the Gulf states and other regional powers to support unconditional peace negotiations with Assad’s regime.

President Obama recently dropped hints that he welcomes further talks with Russia toward that end, in the face of prospects of an eventual jihadist takeover of Syria. Americans who value human rights and peace ahead of overthrowing Arab regimes should welcome such a new policy direction.

[Part Two of this two-part series is available at “Hidden Origins of Syria’s Civil War.“]

Jonathan Marshall is an independent researcher living in San Anselmo, California. Some of his previous articles for Consortiumnews were “Risky Blowback from Russian Sanctions”; “Neocons Want Regime Change in Iran”; “Saudi Cash Wins France’s Favor”; “The Saudis’ Hurt Feelings”; and “Saudi Arabia’s Nuclear Bluster.”]