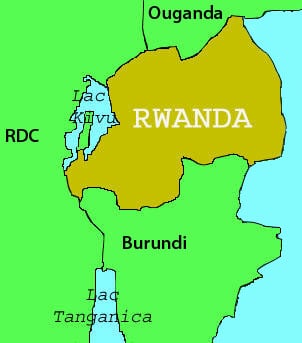

Rwanda: Installing a US Protectorate in Central Africa

Originally written in May 2000, the following text was published as Part II of Chapter 7 entitled “Economic Genocide in Rwanda”, of the Second Edition of The Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order , Global Research, Montreal, 2003. It was posted on Global Research in May 2003. This text updates the author’s analysis on Rwanda written in 1995 , which was published in the first edition of Globalization of Poverty, TWN and Zed Books, Penang and London, 1997.

The civil war in Rwanda and the ethnic massacres were an integral part of US foreign policy, carefully staged in accordance with precise strategic and economic objectives.

This analysis written 15 years ago confirms recent revelations regarding the role of the US in establishing a proxy regime in Rwanda led by president Paul Kagame.

The Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order

by

Michel Chossudovsky

Can be ordered directly from GR

From the outset of the Rwandan civil war in 1990, Washington’s hidden agenda consisted in establishing an American sphere of influence in a region historically dominated by France and Belgium. America’s design was to displace France by supporting the Rwandan Patriotic Front and by arming and equipping its military arm, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA)

From the mid-1980s, the Kampala government under President Yoweri Musaveni had become Washington’s African showpiece of “democracy”. Uganda had also become a launchpad for US sponsored guerilla movements into the Sudan, Rwanda and the Congo. Major General Paul Kagame had been head of military intelligence in the Ugandan Armed Forces; he had been trained at the U.S. Army Command and Staff College (CGSC) in Leavenworth, Kansas which focuses on war-fighting and military strategy. Kagame returned from Leavenworth to lead the RPA, shortly after the 1990 invasion.

Prior to the outbreak of the Rwandan civil war, the RPA was part of the Ugandan Armed Forces. Shortly prior to the October 1990 invasion of Rwanda, military labels were switched. From one day to the next, large numbers of Ugandan soldiers joined the ranks of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA). Throughout the civil war, the RPA was supplied from United People’s Defense Forces (UPDF) military bases inside Uganda. The Tutsi commissioned officers in the Ugandan army took over positions in the RPA. The October 1990 invasion by Ugandan forces was presented to public opinion as a war of liberation by a Tutsi led guerilla army.

Militarization of Uganda

The militarization of Uganda was an integral part of US foreign policy. The build-up of the Ugandan UPDF Forces and of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) had been supported by the US and Britain. The British had provided military training at the Jinja military base:

“From 1989 onwards, America supported joint RPF [Rwandan Patriotic Front]-Ugandan attacks upon Rwanda… There were at least 56 ‘situation reports’ in [US] State Department files in 1991… As American and British relations with Uganda and the RPF strengthened, so hostilities between Uganda and Rwanda escalated… By August 1990 the RPF had begun preparing an invasion with the full knowledge and approval of British intelligence. 20

Troops from Rwanda’s RPA and Uganda’s UPDF had also supported John Garang’s People’s Liberation Army in its secessionist war in southern Sudan. Washington was firmly behind these initiatives with covert support provided by the CIA. 21

Moreover, under the Africa Crisis Reaction Initiative (ACRI), Ugandan officers were also being trained by US Special Forces in collaboration with a mercenary outfit, Military Professional Resources Inc (MPRI) which was on contract with the US Department of State. MPRI had provided similar training to the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and the Croatian Armed Forces during the Yugoslav civil war and more recently to the Colombian Military in the context of Plan Colombia.

Militarization and the Ugandan External Debt

The buildup of the Ugandan external debt under President Musaveni coincided chronologically with the Rwandan and Congolese civil wars. With the accession of Musaveni to the presidency in 1986, the Ugandan external debt stood at 1.3 billion dollars. With the gush of fresh money, the external debt spiraled overnight, increasing almost threefold to 3.7 billion by 1997. In fact, Uganda had no outstanding debt to the World Bank at the outset of its “economic recovery program”. By 1997, it owed almost 2 billion dollars solely to the World Bank. 22

Where did the money go? The foreign loans to the Musaveni government had been tagged to support the country’s economic and social reconstruction. In the wake of a protracted civil war, the IMF sponsored “economic stabilization program” required massive budget cuts of all civilian programs.

The World Bank was responsible for monitoring the Ugandan budget on behalf of the creditors. Under the “public expenditure review” (PER), the government was obliged to fully reveal the precise allocation of its budget. In other words, every single category of expenditure –including the budget of the Ministry of Defense– was open to scrutiny by the World Bank. Despite the austerity measures (imposed solely on “civilian” expenditures), the donors had allowed defense spending to increase without impediment.

Part of the money tagged for civilian programs had been diverted into funding the United People’s Defense Force (UPDF) which in turn was involved in military operations in Rwanda and the Congo. The Ugandan external debt was being used to finance these military operations on behalf of Washington with the country and its people ultimately footing the bill. In fact by curbing social expenditures, the austerity measures had facilitated the reallocation of State of revenue in favor of the Ugandan military.

Financing both Sides in the Civil War

A similar process of financing military expenditure from the external debt had occurred in Rwanda under the Habyarimana government. In a cruel irony, both sides in the civil war were financed by the same donors institutions with the World Bank acting as a Watchdog.

The Habyarimana regime had at its disposal an arsenal of military equipment, including 83mm missile launchers, French made Blindicide, Belgian and German made light weaponry, and automatic weapons such as kalachnikovs made in Egypt, China and South Africa [as well as … armored AML-60 and M3 armored vehicles.23 While part of these purchases had been financed by direct military aid from France, the influx of development loans from the World Bank’s soft lending affiliate the International Development Association (IDA), the African Development Fund (AFD), the European Development Fund (EDF) as well as from Germany, the United States, Belgium and Canada had been diverted into funding the military and Interhamwe militia.

A detailed investigation of government files, accounts and correspondence conducted in Rwanda in 1996-97 by the author –together with Belgian economist Pierre Galand– confirmed that many of the arms purchases had been negotiated outside the framework of government to government military aid agreements through various intermediaries and private arms dealers. These transactions –recorded as bona fide government expenditures– had nonetheless been included in the State budget which was under the supervision of the World Bank. Large quantities of machetes and other items used in the 1994 ethnic massacres –routinely classified as “civilian commodities” — had been imported through regular trading channels. 24

According to the files of the National Bank of Rwanda (NBR), some of these imports had been financed in violation of agreements signed with the donors. According to NBR records of import invoices, approximately one million machetes had been imported through various channels including Radio Mille Collines, an organization linked to the Interhamwe militia and used to foment ethnic hatred. 25

The money had been earmarked by the donors to support Rwanda’s economic and social development. It was clearly stipulated that funds could not be used to import: “military expenditures on arms, ammunition and other military material”. 26 In fact, the loan agreement with the World Bank’s IDA was even more stringent. The money could not be used to import civilian commodities such as fuel, foodstuffs, medicine, clothing and footwear “destined for military or paramilitary use”. The records of the NBR nonetheless confirm that the Habyarimana government used World Bank money to finance the import of machetes which had been routinely classified as imports of “civilian commodities.” 27

An army of consultants and auditors had been sent in by World Bank to assess the Habyarimana government’s “policy performance” under the loan agreement.28 The use of donor funds to import machetes and other material used in the massacres of civilians did not show up in the independent audit commissioned by the government and the World Bank. (under the IDA loan agreement. (IDA Credit Agreement. 2271-RW).29 In 1993, the World Bank decided to suspend the disbursement of the second installment of its IDA loan. There had been, according to the World Bank mission unfortunate “slip-ups” and “delays” in policy implementation. The free market reforms were no longer “on track”, the conditionalities –including the privatization of state assets– had not been met. The fact that the country was involved in a civil war was not even mentioned. How the money was spent was never an issue.30

Whereas the World Bank had frozen the second installment (tranche) of the IDA loan, the money granted in 1991 had been deposited in a Special Account at the Banque Bruxelles Lambert in Brussels. This account remained open and accessible to the former regime (in exile), two months after the April 1994 ethnic massacres.31

Postwar Cover-up

In the wake of the civil war, the World Bank sent a mission to Kigali with a view to drafting a so-called loan “Completion Report”.32 This was a routine exercise, largely focussing on macro-economic rather than political issues. The report acknowledged that “the war effort prompted the [former] government to increase substantially spending, well beyond the fiscal targets agreed under the SAP.33 The misappropriation of World Bank money was not mentioned. Instead the Habyarimana government was praised for having “made genuine major efforts– especially in 1991– to reduce domestic and external financial imbalances, eliminate distortions hampering export growth and diversification and introduce market based mechanisms for resource allocation…” 34, The massacres of civilians were not mentioned; from the point of view of the donors, “nothing had happened”. In fact the World Bank completion report failed to even acknowledge the existence of a civil war prior to April 1994.

In the wake of the Civil War: Reinstating the IMF’s Deadly Economic Reforms

In 1995, barely a year after the 1994 ethnic massacres. Rwanda’s external creditors entered into discussions with the Tutsi led RPF government regarding the debts of the former regime which had been used to finance the massacres. The RPF decided to fully recognize the legitimacy of the “odious debts” of the 1990-94. RPF strongman Vice-President Paul Kagame [now President] instructed the Cabinet not to pursue the matter nor to approach the World Bank. Under pressure from Washington, the RPF was not to enter into any form of negotiations, let alone an informal dialogue with the donors.

The legitimacy of the wartime debts was never questioned. Instead, the creditors had carefully set up procedures to ensure their prompt reimbursement. In 1998 at a special donors’ meeting in Stockholm, a Multilateral Trust Fund of 55.2 million dollars was set up under the banner of postwar reconstruction.35 In fact, none of this money was destined for Rwanda. It had been earmarked to service Rwanda’s “odious debts” with the World Bank (–i.e. IDA debt), the African Development Bank and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD).

In other words, “fresh money” –which Rwanda will eventually have to reimburse– was lent to enable Rwanda to service the debts used to finance the massacres. Old loans had been swapped for new debts under the banner of post-war reconstruction.36 The “odious debts” had been whitewashed, they had disappeared from the books. The creditor’s responsibility had been erased. Moreover, the scam was also conditional upon the acceptance of a new wave of IMF-World Bank reforms.

Post War “Reconstruction and Reconciliation”

Bitter economic medicine was imposed under the banner of “reconstruction and reconciliation”. In fact the IMF post-conflict reform package was far stringent than that imposed at the outset of the civil war in 1990. While wages and employment had fallen to abysmally low levels, the IMF had demanded a freeze on civil service wages alongside a massive retrenchment of teachers and health workers. The objective was to “restore macro-economic stability”. A downsizing of the civil service was launched.37 Civil service wages were not to exceed 4.5 percent of GDP, so-called “unqualified civil servants” (mainly teachers) were to be removed from the State payroll. 38

Meanwhile, the country’s per capita income had collapsed from $360 (prior to the war) to $140 in 1995. State revenues had been tagged to service the external debt. Kigali’s Paris Club debts were rescheduled in exchange for “free market” reforms. Remaining State assets were sold off to foreign capital at bargain prices.

The Tutsi led RPF government rather than demanding the cancellation of Rwanda’s odious debts, had welcomed the Bretton Woods institutions with open arms. They needed the IMF “greenlight” to boost the development of the military.

Despite the austerity measures, defense expenditure continued to grow. The 1990-94 pattern had been reinstated. The development loans granted since 1995 were not used to finance the country’s economic and social development. Outside money had again been diverted into financing a military buildup, this time of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA). And this build-up of the RPA occurred in the period immediately preceding the outbreak of civil war in former Zaire.

Civil War in the Congo

Following the installation of a US client regime in Rwanda in 1994, US trained Rwandan and Ugandan forces intervened in former Zaire –a stronghold of French and Belgian influence under President Mobutu Sese Seko. Amply documented, US special operations troops — mainly Green Berets from the 3rd Special Forces Group based at Fort Bragg, N.C.– had been actively training the RPA. This program was a continuation of the covert support and military aid provided to the RPA prior to 1994. In turn, the tragic outcome of the Rwandan civil war including the refugee crisis had set the stage for the participation of Ugandan and Rwandan RPA in the civil war in the Congo:

“Washington pumped military aid into Kagame’s army, and U.S. Army Special Forces and other military personnel trained hundreds of Rwandan troops. But Kagame and his colleagues had designs of their own. While the Green Berets trained the Rwandan Patriotic Army, that army was itself secretly training Zairian rebels.… [In] Rwanda, U.S. officials publicly portrayed their engagement with the army as almost entirely devoted to human rights training. But the Special Forces exercises also covered other areas, including combat skills… Hundreds of soldiers and officers were enrolled in U.S. training programs, both in Rwanda and in the United States… [C]onducted by U.S. Special Forces, Rwandans studied camouflage techniques, small-unit movement, troop-leading procedures, soldier-team development, [etc]… And while the training went on, U.S. officials were meeting regularly with Kagame and other senior Rwandan leaders to discuss the continuing military threat faced by the [former Rwandan] government [in exile] from inside Zaire… Clearly, the focus of Rwandan-U.S. military discussion had shifted from how to build human rights to how to combat an insurgency… With [Ugandan President] Museveni’s support, Kagame conceived a plan to back a rebel movement in eastern Zaire [headed by Laurent Desire Kabila] … The operation was launched in October 1996, just a few weeks after Kagame’s trip to Washington and the completion of the Special Forces training mission… Once the war [in the Congo] started, the United States provided “political assistance” to Rwanda,… An official of the U.S. Embassy in Kigali traveled to eastern Zaire numerous times to liaise with Kabila. Soon, the rebels had moved on. Brushing off the Zairian army with the help of the Rwandan forces, they marched through Africa’s third-largest nation in seven months, with only a few significant military engagements. Mobutu fled the capital, Kinshasa, in May 1997, and Kabila took power, changing the name of the country to Congo…U.S. officials deny that there were any U.S. military personnel with Rwandan troops in Zaire during the war, although unconfirmed reports of a U.S. advisory presence have circulated in the region since the war’s earliest days.39

American Mining Interests

At stake in these military operations in the Congo were the extensive mining resources of Eastern and Southern Zaire including strategic reserves of cobalt — of crucial importance for the US defense industry. During the civil war several months before the downfall of Mobutu, Laurent Desire Kabila basedin Goma, Eastern Zaire had renegotiated the mining contracts with several US and British mining companies including American Mineral Fields (AMF), a company headquartered in President Bill Clinton’s hometown of Hope, Arkansas.40

Meanwhile back in Washington, IMF officials were busy reviewing Zaire’s macro-economic situation. No time was lost. The post-Mobutu economic agenda had already been decided upon. In a study released in April 1997 barely a month before President Mobutu Sese Seko fled the country, the IMF had recommended “halting currency issue completely and abruptly” as part of an economic recovery programme.41 And a few months later upon assuming power in Kinshasa, the new government of Laurent Kabila Desire was ordered by the IMF to freeze civil service wages with a view to “restoring macro-economic stability.” Eroded by hyperinflation, the average public sector wage had fallen to 30,000 new Zaires (NZ) a month, the equivalent of one U.S. dollar.42

The IMF’s demands were tantamount to maintaining the entire population in abysmal poverty. They precluded from the outset a meaningful post-war economic reconstruction, thereby contributing to fuelling the continuation of the Congolese civil war in which close to 2 million people have died.

Concluding Remarks

The civil war in Rwanda was a brutal struggle for political power between the Hutu-led Habyarimana government supported by France and the Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) backed financially and militarily by Washington. Ethnic rivalries were used deliberately in the pursuit of geopolitical objectives. Both the CIA and French intelligence were involved.

In the words of former Cooperation Minister Bernard Debré in the government of Prime Minister Henri Balladur:

“What one forgets to say is that, if France was on one side, the Americans were on the other, arming the Tutsis who armed the Ugandans. I don’t want to portray a showdown between the French and the Anglo-Saxons, but the truth must be told.” 43

In addition to military aid to the warring factions, the influx of development loans played an important role in “financing the conflict.” In other words, both the Ugandan and Rwanda external debts were diverted into supporting the military and paramilitary. Uganda’s external debt increased by more than 2 billion dollars, –i.e. at a significantly faster pace than that of Rwanda (an increase of approximately 250 million dollars from 1990 to 1994). In retrospect, the RPA — financed by US military aid and Uganda’s external debt– was much better equipped and trained than the Forces Armées du Rwanda (FAR) loyal to President Habyarimana. From the outset, the RPA had a definite military advantage over the FAR.

According to the testimony of Paul Mugabe, a former member of the RPF High Command Unit, Major General Paul Kagame had personally ordered the shooting down of President Habyarimana’s plane with a view to taking control of the country. He was fully aware that the assassination of Habyarimana would unleash “a genocide” against Tutsi civilians. RPA forces had been fully deployed in Kigali at the time the ethnic massacres took place and did not act to prevent it from happening:

The decision of Paul Kagame to shoot Pres. Habyarimana’s aircraft was the catalyst of an unprecedented drama in Rwandan history, and Major-General Paul Kagame took that decision with all awareness. Kagame’s ambition caused the extermination of all of our families: Tutsis, Hutus and Twas. We all lost. Kagame’s take-over took away the lives of a large number of Tutsis and caused the unnecessary exodus of millions of Hutus, many of whom were innocent under the hands of the genocide ringleaders. Some naive Rwandans proclaimed Kagame as their savior, but time has demonstrated that it was he who caused our suffering and misfortunes… Can Kagame explain to the Rwandan people why he sent Claude Dusaidi and Charles Muligande to New York and Washington to stop the UN military intervention which was supposed to be sent and protect the Rwandan people from the genocide? The reason behind avoiding that military intervention was to allow the RPF leadership the takeover of the Kigali Government and to show the world that they – the RPF – were the ones who stopped the genocide. We will all remember that the genocide occurred during three months, even though Kagame has said that he was capable of stopping it the first week after the aircraft crash. Can Major-General Paul Kagame explain why he asked to MINUAR to leave Rwandan soil within hours while the UN was examining the possibility of increasing its troops in Rwanda in order to stop the genocide?44

Paul Mugabe’s testimony regarding the shooting down of Habyarimana’s plane ordered by Kagame is corroborated by intelligence documents and information presented to the French parliamentary inquiry. Major General Paul Kagame was an instrument of Washington. The loss of African lives did not matter. The civil war in Rwanda and the ethnic massacres were an integral part of US foreign policy, carefully staged in accordance with precise strategic and economic objectives.

Despite the good diplomatic relations between Paris and Washington and the apparent unity of the Western military alliance, it was an undeclared war between France and America. By supporting the build up of Ugandan and Rwandan forces and by directly intervening in the Congolese civil war, Washington also bears a direct responsibility for the ethnic massacres committed in the Eastern Congo including several hundred thousand people who died in refugee camps.

US policy-makers were fully aware that a catastrophe was imminent. In fact four months before the genocide, the CIA had warned the US State Department in a confidential brief that the Arusha Accords would fail and “that if hostilities resumed, then upward of half a million people would die”. 45 This information was withheld from the United Nations: “it was not until the genocide was over that information was passed to Maj.-Gen. Dallaire [who was in charge of UN forces in Rwanda].” 46

Washington’s objective was to displace France, discredit the French government (which had supported the Habyarimana regime) and install an Anglo-American protectorate in Rwanda under Major General Paul Kagame. Washington deliberately did nothing to prevent the ethnic massacres.

When a UN force was put forth, Major General Paul Kagame sought to delay its implementation stating that he would only accept a peacekeeping force once the RPA was in control of Kigali. Kagame “feared [that] the proposed United Nations force of more than 5,000 troops… [might] intervene to deprive them [the RPA] of victory”.47 Meanwhile the Security Council after deliberation and a report from Secretary General Boutros Boutros Ghali decided to postpone its intervention.

The 1994 Rwandan “genocide” served strictly strategic and geopolitical objectives. The ethnic massacres were a stumbling blow to France’s credibility which enabled the US to establish a neocolonial foothold in Central Africa. From a distinctly Franco-Belgian colonial setting, the Rwandan capital Kigali has become –under the expatriate Tutsi led RPF government– distinctly Anglo-American. English has become the dominant language in government and the private sector. Many private businesses owned by Hutus were taken over in 1994 by returning Tutsi expatriates. The latter had been exiled in Anglophone Africa, the US and Britain.

The Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) functions in English and Kinyarwanda, the University previously linked to France and Belgium functions in English. While English had become an official language alongside French and Kinyarwanda, French political and cultural influence will eventually be erased. Washington has become the new colonial master of a francophone country.

Several other francophone countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have entered into military cooperation agreements with the US. These countries are slated by Washington to follow suit on the pattern set in Rwanda. Meanwhile in francophone West Africa, the US dollar is rapidly displacing the CFA Franc — which is linked in a currency board arrangement to the French Treasury.

Notes (Endnote numbering as in the original chapter)

Written in 1999, the following text is Part II of Chapter 5 of the Second Edition of The Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order. The first part of chapter published in the first edition was written in 1994. Part II is in part based on a study conducted by the author and Belgian economist Pierre Galand on the use of Rwanda’s 1990-94 external debt to finance the military and paramilitary.

- Africa Direct, Submission to the UN Tribunal on Rwanda, http://www.junius.co.uk/africa- direct/tribunal.html Ibid.

- Africa’s New Look, Jane’s Foreign Report, August 14, 1997.

- Jim Mugunga, Uganda foreign debt hits Shs 4 trillion, The Monitor, Kampala, 19 February 1997.

- Michel Chossudovsky and Pierre Galand, L’usage de la dette exterieure du Rwanda, la responsabilité des créanciers, mission report, United Nations Development Program and Government of Rwanda, Ottawa and Brussels, 1997.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- ibid, the imports recorded were of the order of kg. 500.000 of machetes or approximately one million machetes.

- Ibid

- Ibid. See also schedule 1.2 of the Development Credit Agreement with IDA, Washington, 27 June 1991, CREDIT IDA 2271 RW.

- Chossudovsky and Galand, op cit

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- World Bank completion report, quoted in Chossudovsky and Galand, op cit.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- See World Bank, Rwanda at http://www.worldbank.org/afr/rw2.htm.

- Ibid, italics added

- A ceiling on the number of public employees had been set at 38,000 for 1998 down from 40,600 in 1997. See Letter of Intent of the Government of Rwanda including cover letter addressed to IMF Managing Director Michel Camdessus, IMF, Washington, http://www.imf.org/external/np/loi/060498.htm , 1998.

- Ibid.

- Lynne Duke Africans Use US Military Training in Unexpected Ways, Washington Post. July 14, 1998; p.A01.

- Musengwa Kayaya, U.S. Company To Invest in Zaire, Pan African News, 9 May 1997.

- International Monetary Fund, Zaire Hyperinflation 1990-1996, Washington, April 1997.

- Alain Shungu Ngongo, Zaire-Economy: How to Survive On a Dollar a Month, International Press Service, 6 June 1996.

- Quoted in Therese LeClerc. “Who is responsible for the genocide in Rwanda?”, World Socialist website at http://www.wsws.org/index.shtml , 29 April 1998.

- Paul Mugabe, The Shooting Down Of The Aircraft Carrying Rwandan President Habyarimama , testimony to the International Strategic Studies Association (ISSA), Alexandria, Virginia, 24 April 2000.

- Linda Melvern, Betrayal of the Century, Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa, 8 April 2000.

- Ibid

- Scott Peterson, Peacekeepers will not halt carnage, say Rwanda, rebels, Daily Telegraph, London, May 12, 1994.