|

Wherever there are reports of melting glaciers and a future of diminished water resources, there is an increasing Balkanization of nation-states. Those who manipulate world events for maximum profit understand that it is much easier to control water resources if one is dealing with a multitude of warring and jealous mini-states than it is to deal with a regional power…

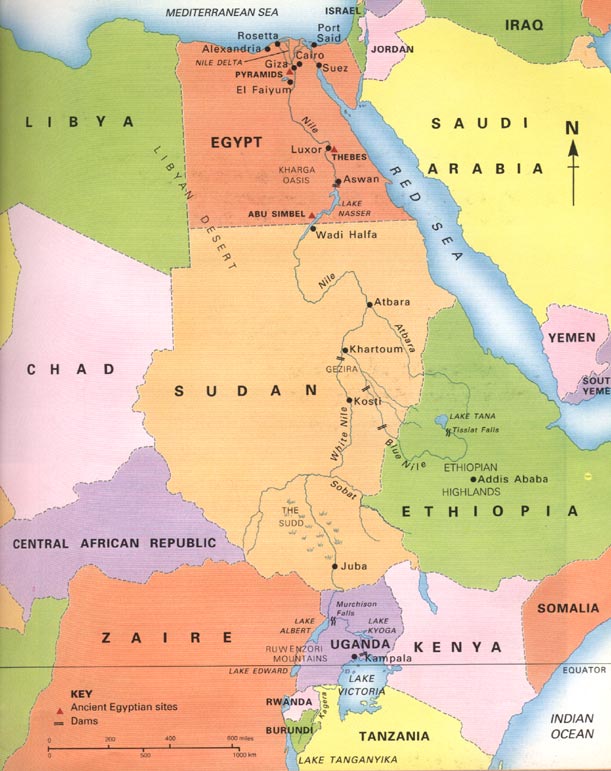

The Nile Basin is seeing record fragmentation of nation-states by secessionist and other rebel movements, some backed by the United States and its Western allies and others backed by Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Yet other secessionist groups are backed by regional rivals such as Ethiopia, Eritrea, Uganda, and Sudan.

Ethiopia has announced that its Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project on the Blue Nile will begin diverting the Blue Nile at the end of 2014. Ethiopia’s decision has set off alarm bells down river in Sudan and Egypt, which are both critically dependent on the Nile for drinking water, irrigation, and in the case of Egypt’s Aswan High Dam, electric power. A 1959 agreement between Egypt and Sudan guarantees Egypt 70 percent and Sudan 30 percent of the Nile’s water flow.

Egypt’s government has warned Ethiopia, a historical rival, not to restrict the Nile water flow to the extent that it would adversely affect the Aswan Dam or Egypt’s water supply. Sudan has voiced similar warnings. Cairo and Khartoum are also aware that their mutual enemy, Israel, has close relations with Ethiopia and the Republic of South Sudan, the world’s newest nation. The independence of South Sudan would not have been possible without the backing of Israel’s leading neo-conservative allies in Washington and London.

The White Nile flows from the Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, through Uganda and South Sudan, to Sudan. Egypt and Sudan have also been concerned about Israel’s heavy presence in South Sudan. The South Sudanese secession put tremendous pressure on the future territorial integrity of Sudan, which faces additional Western- and Israeli-backed breakaway movements in Darfur and northeastern Sudan.

Independence for South Sudan was long a goal of former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and her god-daughter, current U.S. ambassador to the UN Susan Rice. The splitting of Sudan into an Arab Muslim north and a black Christian and animist south was also long a goal of Israel, which yearned for a client state in South Sudan that would be able to squeeze the supply of the Nile’s headwaters to Egypt and north Sudan.

South Sudan’s independence was cobbled together so rapidly, its Western sponsors were not even sure, at first, what to call the country. Although South Sudan was finally agreed upon, other proposals were to call the nation the «Nile Republic» or «Nilotia,» which were rejected because of the obvious threatening meaning that such names would send to Cairo and Khartoum.

The names «Cush» or «Kush» were also rejected because of their reference to the land of Cush that appears in the Jewish Bible and the obvious meaning that such a name would have for those who accuse Israel of wanting to expand its borders beyond the borders of the Palestinian mandate. «New Sudan» was also rejected because of implied irredentist claims by South Sudan on the contested oil-rich Abyei region between Sudan and South Sudan.

Egypt has been lending quiet support to Ethiopian and Somali secessionists, which Cairo sees as a counterweight to Ethiopian neo-imperialist designs in the Horn of Africa. Although Ethiopia maintains good relations with the breakaway Republic of Somaliland, Addis Ababa does not want to see Somalia fragmented any further. But that is exactly what is desired by Cairo to keep Ethiopia’s military and revenues preoccupied with an unstable and collapsing neighbor to the east.

Two other parts of Somalia, Puntland and Jubaland, also spelled Jubbaland, have declared separatist states. Jubaland should not be confused with the capital of South Sudan, Juba, which is being relocated to Ramciel, close to the border with Sudan. However, all this confusion and map redrawing is a result of increasing hydropolitics in the region, as well as the ever-present turmoil caused by the presence of oil and natural gas reserves. The Rahanweyn Resistance Army is fighting for an independent state of Southwestern Somalia.

Somaliland has its own secessionist movement in the western part of the country, an entity called Awdalland, which is believed to get some support from neighboring Djibouti, the site of the U.S. military base at Camp Lemonier.

Ethiopian troops, supported by the African Union and the United States, are trying to prop up Somalia’s weak Federal government but Somalia’s fracturing continues unabated with Kenya supporting a semi-independent entity called «Azania» in a part of Jubaland in Somalia.

There are also a number of nascent separatist movements in Ethiopia, many being brutally suppressed by the Ethiopian government with military assistance from the United States, Britain, and Israel. Some of these movements are backed by Eritrea, which, itself, broke away from Ethiopia two decades ago. Chief among the groups are the Ogadenis, who want a Somali state declared in eastern Ethiopia and the Oromo, who dream of an independent Oromia.

Ethiopia’s ruling dictatorship has tried to placate the Oromos and Ogadenis with peace talks but these moves are seen as window dressing to placate Ethiopia’s benefactors in Washington and London.

However, separatist movements throughout the Horn of Africa took pleasure in the advent of South Sudan because they saw the «inviolability» of colonial-drawn borders, long insisted upon by the Organization of African Unity and the African Union, finally beginning to wither. In fact, that process began with Eritrea’s independence in 1993. Eritrea also faces its own secessionist movement, the Red Sea Afars. The Afars also maintain separatist movements in Ethiopia and Djibouti, the latter having once been known as the French Territory of the Afars and Issas.

In another U.S. ally, Kenya, the homeland of President Barack Obama’s father, Muslims along the coast have dusted off the Sultan of Zanzibar’s 1887 lease to the British East Africa Company of the 10-mile strip of land along the present Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. Legally, when the lease expired the strip was to revert back to control of the sultan. Since the Sultan was ousted in a 1964 coup, the coastal Kenyans argue that the coastal strip was annexed illegally by Kenya and that, therefore, the coastal strip should be the independent Republic of Pwani. The discovery of major oil and natural gas reserves in Uganda and South Sudan has resulted in plans for pipelines to be built to the port of Mombasa, the would-be capital of Pwani on the Indian Ocean. In Kenya, hydropolitics and petropolitics in the Horn of Africa has resulted in Balkanization spilling into Kenya.

In the Himalayas, glacier retreat and rapidly diminishing snow cover are also adding to hydropolitical angst and fueling separatist movements backed by the bigger powers in the region: India, China, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Snow melt is now being seen in some parts of the Himalayas in December and January. Four dams on the Teesta River, which flows from Sikkim through north Bengal to the Brahmaputra basin, have not only affected the geo-political situation in Sikkim, which has nascent independence and Nepali irredentist movements, but also helps to fuel demands for increased autonomy for Gorkhaland, Bodoland, and Assam, an independent Madhesistan in southern Nepal, an ethnic Nepali revolt in southern Bhutan, and consternation in Bangladesh, where the Brahmaputra and Ganges converge to largely support a country with a population of 161 million people. Bangladesh has also seen its share of secessionist movements, including the Bangabhumi Hindu and the Chittagong Hill Tracts movements.

Hydropolitics, petropolitics, and the status quo, like water and oil, do not mix, especially when it comes to the preservation of current borders. Northeastern Africa and South Asia are not unique in this respect.

|