|

The European Court of Human Rights is refusing to act on a year-old case from the daughter of a Dutch passenger killed when Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 was shot down on July 14, 2014. Denise Kenke, daughter of Willem Grootscholten, accuses the Ukraine Government of failing its legal duty to prevent civilian aircraft from flying into the airspace Ukrainian officials knew to be dangerous. Her court papers say the claim is also founded on the conclusion of the Dutch Safety Board, reported last October, that the government in Kiev had been negligent in failing to act on “sufficient reason for closing the airspace above the eastern part of Ukraine”.

Although the 11-page application was filed on November 17, 2014, the Court has imposed a secrecy blackout on all details of the case, preventing website access. After Kenke’s lawyer, Elmar Giemulla of Berlin, a leading German aviation law specialist, filed additional argument, legal precedents, and evidence from the Dutch Safety Board (DSB), the Court refu nosed to acknowledge receipt or to reply. Tracey Turner-Tretz, spokesman for the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and its registrar, Roderick Liddell, a British national, said this week: “the application in question was granted confidentiality.”

Giemulla for the Grootscholten family said he had not applied for confidentiality, and was not informed by the court that it had been imposed.

“I do not know anything about ‘grant of confidentiality’ . I do not even know whether the court has ever dealt with my complaint apart from internal administrative procedures.”

When Liddell and his spokesman Turner-Tretz were asked what communication the Court has been having on the Kenke case with Ukraine government representatives, and whether Kiev had requested confidentiality, they refused to reply. A US attorney with a US and Ukraine practice says

“it’s not possible for a US court to seal a case from public disclosure without argument in court by lawyers from both sides, and without a recorded ruling.”

From Berlin, Giemulla said this morning: “Someone, I don’t know who, has decided that this case is confidential — from the plaintiff!”

Malaysian Airlines assigned Grootscholten (below, left) seat 11D on MH17. He was on his way to his Indonesian fiancé Christine (right).

For more details of Grootscholten’s life and death, see this memorial video. For more details of Grootscholten’s life and death, see this memorial video.

His daughter’s application was submitted by Giemulla in November 2014, well within the 6-month time limit required by the ECHR between the cause of the complaint and the filing. Additional papers were filed in January 2015, and the case was assigned case number 4412/15. On March 9, 2015, Giemulla wrote the court asking for confirmation of the proceeding. He received a reply “advis[ing] me not to bother the court by phone considering its high work load. That´s all.”

If the attempt is made to search the court website, there is no trace of the case. On September 4, 2015, Giemulla (right) submitted additional evidence from the newly released DSB report, together with 7 pages of legal argument. The ECHR refused to acknowledge receipt. Last week, Giemulla wrote the ECHR again. “With urgency may I ask to be informed [by the Registrar] about the state of the present proceeding and the other steps intended by the Court.” If the attempt is made to search the court website, there is no trace of the case. On September 4, 2015, Giemulla (right) submitted additional evidence from the newly released DSB report, together with 7 pages of legal argument. The ECHR refused to acknowledge receipt. Last week, Giemulla wrote the ECHR again. “With urgency may I ask to be informed [by the Registrar] about the state of the present proceeding and the other steps intended by the Court.”

Giemulla is well-known in Germany as a specialist on public liability for air crashes. He is also representing kin of German passengers killed in the Lufthansa pilot suicide crash of Germanwings Flight 4U 9525 in France in March 2015.

The case against the Ukrainian Government in Kiev does not depend, Giemulla has argued in the ECHR papers, on evidence or speculation about what weapon brought down MH17; who fired it; or what the cause of death for passengers and crew had been. This evidence, and the lack of it, were tested in an international court for the first time last month; that’s when a coroner’s court in the Australian state of Victoria held an inquest on the deaths of Australian passengers on MH17. For reports of that court proceeding, read this and this.

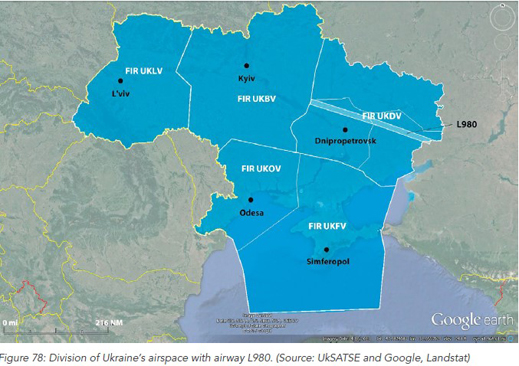

“The final report of the Dutch Safety Board from October, 2015, supports the view”, Giemulla testified to the ECHR in September, “that the government of the Ukraine bears the responsibility for the disaster because it has not closed the airspace above eastern Ukraine at the altitude of the flight plan in spite of knowledge of the circumstances.” In support, he has submitted the DSB report’s analysis of Ukrainian airspace management, military operations in the eastern region airspace, and Ukrainian government officials’ failure to protect civil aviation in the Dniepropetrovsk air traffic control area through which MH17’s flight path, L980, crossed.

Source: DSB Report of October 13, 2015:

http://www.onderzoeksraad.nl/en/onderzoek/2049/investigation-crash-mh17-17-july-2014

The DSB report noted that airspace below the MH17’s altitude had been restricted, but that its flight path L980 at 30,000 feet was open. The DSB concluded the Ukrainian military were responsible for deciding on airspace controls, and that “the Ukrainian authorities took insufficient notice of the possibility of of a civil aeroplane at cruising altitude being fired upon… No measures were taken to protect civil aeroplanes against these weapon systems… the sovereign state bears sole responsibility for the safety of the airspace” (DSB report, page 209). The DSB also noted, without definitive conclusion, that “considerations other than those related to safety could also have played a part in Ukraine’s decision not to completely close the airspace to civil aviation, such as possible financial consequences [loss of overflight fees]. A complete closure may also have given the impression that the state had lost control over a part of its airspace.”

Published estimates from Washington indicate that before the MH17 crash, the government in Kiev was collecting $200 million per annum in overflight and air transit fees.

Giemulla has put the government in Kiev directly on trial in an international court for the first time in the MH17 case. The coronial court proceeding in Australia, and thepostponed inquests in the UK, are investigations of cause of death, and only indirectly address responsibility in Kiev. Giemulla’s written submission to the ECHR is that Kiev is now liable to pay compensation for the death of passenger Grootscholten. “The Ukrainian government was… obliged to close the airspace concerned. Contrary to its legal obligation, it has not blocked the airspace at cruising altitude. This caused, inter alia, the death of the father [Grootscholten] of the complainant [Kenke].” The actions of the Ukrainian government in not closing the airspace had been “intentional actions”, the court papers argue. “The Ukrainian government has failed to meet its legal obligation to avert an existing danger to human life by obvious and available measures.”

In a separate submission, Giemulla has also told the ECHR the Ukrainian courts and their judges are too easily subject to political intervention to provide a remedy for MH17 claims. Giemulla told the court it was not appropriate or relevant to determine who fired the weapon or what caused the crash. “It cannot be judged from the outside which is the correct one of the versions [of cause of crash] and what actually happened. Regardless, it can be understood that in this critical situation the Ukrainian courts have been reluctant to deal with the investigation of the facts and [reluctant to] condemn their government…”

In legal support, Giemulla cited the ECHR’s own rulings on the corruption and bias of Ukrainian judges. “The ECtHR has in the case of Tymoshenko v. Ukraine of 30 July 2013 (Application No 49872/11, S. 41 and 45), and with reference to the earlier case Kaverzin v. Ukraine (Application No 2389/03) adopted an exception to the requirement for exhaustion of legal remedies in the domestic courts, in accordance with Article 35, on the ground that that the available [court] remedies were not capable of ensuring effective legal protection.”

This is a reference to Yulia Tymoshenko’s claim to the ECHR that her conviction and imprisonment by the Ukrainian courts in 2011 had been politically motivated. For more on that case, read this.

Tymoshenko (above, left) as prime minister in Kiev had supervised the appointment of Ganna Yudkivska (right) to the list of ECHR judges, following political infighting in Kiev, and controversy at ECHR headquarters in Strasbourg, over manipulation of theappointment. Yudkivska has not only defended the new regime in Kiev on the court bench. She lectured at Harvard University last year on how the court is defending “democratization processes” in the Ukraine. For more on Yudkivska, read this.

ECHR documents indicate this Ukrainian judge has been involved in the MH17 case, and almost certainly that she has supported the Kiev government’s request for the blackout — the decision to issue what Registrar Liddell calls the “grant of confidentiality”.

Liddell said this week, through Turner-Tretz, that in March 2015 he had “informed the applicant [Kenke, Giemulla] by letter of the registration of the application. The letter specified in particular that the Court would deal with the case as soon as practicable on the basis of the information and documents submitted by her and that she would be informed of any decision taken by the Court. Generally speaking, it is difficult to say how long the processing of an application will take, as this may depend on a number of factors. The order of dealing with cases is governed by Rule 41 of the Rules of Court and further specified in its priority policy.”

The ECHR’s Rule 41 says: “In determining the order in which cases are to be dealt with, the Court shall have regard to the importance and urgency of the issues raised on the basis of criteria fixed by it. The Chamber, or its President, may, however, derogate from these criteria so as to give priority to a particular application.” The ECHR policy statement referred to says that “according to this Rule [41] the Court is to have regard to the importance and urgency of the issues raised in deciding the order in which cases are to be dealt with.”

In a series of email exchanges this week, Turner-Tretz refused to disclose Liddell’s name as the ECHR registrar. This was despite the publication on the court blog that his appointment commenced last month.

Through his spokesman Turner-Tretz (above, right), Liddell (left) was asked: what notification has the Court Registrar made to the Defendant, the Government of Ukraine, and on what date? What response filing has been made in the case by the Government of Ukraine? On what application, on what date, and from what source was the application for confidentiality made? What Court official authorized on what date what you report as the “grant [of] confidentiality”?

Liddell refused to answer. Giemulla suspects the Ukrainian government has been informed of the case, and is likely to have been given the case papers. He says the ECHR has withheld these communications from him, if it has made them.

Liddell has sent an email to say “please note that the case was given confidential status under Rule 33 (public character of documents) of the Rules of Court. This decision was taken by the President of the Chamber to which the case has been allocated.”

Court rules of procedure reveal that in the Chamber section which is considering the MH17 case in secret, Ukrainian judge Yudkivska is a member. Court rules of procedure say: “Chamber: composed of 7 judges, chambers primarily rule on admissibility and merits for cases that raise issues that have not been ruled on repeatedly (a decision may be made by a majority). Each chamber includes the Section President and the ‘national judge’ (the judge with the nationality of the State against which the application is lodged).”

Yesterday Liddell’s spokesman Turner-Tretz was asked to name the president of the chamber to which Liddell now admits the MH17 case has been allocated. “In normal court jurisdictions,” Turner-Tretz was told, “a ruling to seal a case file cannot be made without an application by one of the parties and a hearing before representatives of all parties; the ruling to seal cannot lawfully be taken in secret by a judge keeping his or her name secret. You will be reported by name as speaking for Roderick Liddell, your new Registrar, as confirming that the Court has communicated in secret with the Defendant in this case, and is attempting to keep every detail of the case secret.”

Liddell replied: “the decision to grant confidentiality was taken by Judge Casadevall, President of the Third Section. Subsequently, following the recomposition of the Sections with effect from 1 November 2015, the case was reassigned to a new Section, the First Section, presided over by Mirjana Lazarova–Trajkovska, judge in respect of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.” The implication is that Judge Josep Casadevall — an Andorran who has served on the ECHR bench since its establishment in 1998 — was taken off the MH17 case.

Lazarova-Trajkovska was appointed to the ECHR in 2008. Before that, she had been a Macedonian Interior Ministry lawyer, then the director of the state election commission during the controversial parliamentary campaign of 2002. Then, as well as earlier in her career, she has been aided by grants from the US Government. Following the outcome of the 2002 poll, she was briefly a judge of the Macedonian Constitutional Court until the government in Skopje moved her to the ECHR. Lazarova-Trajkovska was appointed to the ECHR in 2008. Before that, she had been a Macedonian Interior Ministry lawyer, then the director of the state election commission during the controversial parliamentary campaign of 2002. Then, as well as earlier in her career, she has been aided by grants from the US Government. Following the outcome of the 2002 poll, she was briefly a judge of the Macedonian Constitutional Court until the government in Skopje moved her to the ECHR.

London lawyers who follow ECHR proceedings closely don’t doubt that in the MH17 case the Registrar and the judges have been made aware of the Ukrainian government’s reaction. The sources believe Kiev officials have sought Yudkivska’s ruling, along with that of the Macedonian judge, to reject the Kenke case as inadmissible; close down the application without argument in open court; and keep this process secret. Dutch sources add that the Ukrainian government is pressuring the ECHR to block all claims from eastern Ukraine, as well as from the MH17 shoot-down. French lawyers have been attempting to file dozens of claims on behalf of victims of the Ukrainian military operations in Donbass.

A UK human rights lawyer says the ECHR has become “notorious” for its onesidedness and political prejudice. “It’s now a Star Chamber”, he said, referring to the court run by British monarchs from the 15th century until the overthrow of King Charles I in 1641. The Star Chamber operated in secret, and its name has become synonymous with politically motivated prosecution.

According to ECHR documents, “a case may be inadmissible when it is incompatible with the requirements of ratione materiae, ratione temporis or ratione personae, or if the case cannot be proceeded with on formal grounds, such as non-exhaustion of domestic remedies, lapse of the six months from the last internal decision complained of, anonymity, substantial identity with a matter already submitted to the Court, or with another procedure of international investigation. If the rapporteur judge decides that the case can proceed, the case is referred to a Chamber of the Court which, unless it decides that the application is inadmissible, communicates the case to the government of the state against which the application is made, asking the government to present its observations on the case. The Chamber of Court then deliberates and judges the case on its admissibility and its merit.”

Giemulla’s submissions make it difficult for the ECHR judges to rule that the case should go to the Ukrainian courts. His papers have also met the deadline of time set by the court. Sources close to the MH17 case in Strasbourg believe Lazarova-Trajkovska and Yudkivska have been told by Kiev that they should dismiss the case because the Joint Investigation Team (JIT) of prosecutors of The Netherlands, Australia, Ukraine, Belgium and Malaysia are conducting “another procedure of international investigation”.

According to the plaintiff’s court papers, the forensic investigation of the cause of the crash and the culprits is an entirely different case, and cannot be the ground for dismissing the Kenke application. Liddell is concealing the argument on these issues between the defendant and the judges.

Liddell replied: “the case was given confidential status under Rule 33 (public character of documents) of the Rules of Court.”

The text of this rule is much more limited than Liddell’s action has proved to be. “Public access,” Rule 33 declares, “to a document or to any part of it may be restricted in the interests of morals, public order or national security in a democratic society, where the interests of juveniles or the protection of the private life of the parties or of any person concerned so require, or to the extent strictly necessary in the opinion of the President of the Chamber in special circumstances where publicity would prejudice the interests of justice. Any request for confidentiality made under paragraph 1 of this Rule must include reasons and specify whether it is requested that all or part of the documents be inaccessible to the public.”

|